Max Skladanowsky

Max Skladanowsky (30 April 1863 – 30 November 1939) was a

Career

Born as the fourth child of glazier Carl Theodor Skladanowsky (1830–1897) and Luise Auguste Ernestine Skladanowsky, Max Skladanowsky was apprenticed as a photographer and glass painter, which led to an interest in magic lanterns. In 1879, he began to tour Germany and Central Europe with his father Carl and elder brother Emil, giving dissolving magic lantern shows. While Emil mostly took care of promotion, Max was mostly involved with the technology and for instance developed special multi-lens devices that allowed simultaneous projection of up to nine separate image sequences. Carl retired from this show business, but Max and Emil continued and added other attractions,[1] including a type of naumachia that involved electro-mechanical effects and pyrotechnics.

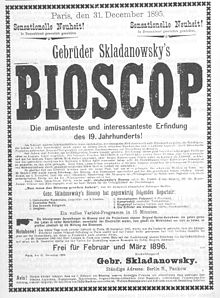

Max would later claim to have constructed their first film camera on 20 August 1892, but this more likely happened in the summer or autumn of 1894. He also single-handedly constructed the Bioskop projector. Partially based on the dissolving view lantern, it featured two lenses and two separate film reels, one frame being projected alternately from each. It was hand-cranked to transport 44.5mm-wide unperforated Eastman-Kodak film-stock, which was carefully cut, perforated and re-assembled by hand and coated with an emulsion developed by Max. The projector was placed behind a screen, which was made properly transparent by keeping it wet to show the images optimally.[1]

The Skladanowsky brothers shot several films in May 1895. Their first film recorded Emil performing overstated movements on a rooftop with a panorama of Berlin in the background. This was an experimental test, not to be used in their commercial screenings. Their further choice of subjects seemed influenced by the films they probably viewed in the Kinetoscope that was installed in Berlin in March. They filmed various variety acts who were performing in town and had them perform in the gardens of theatres in full sunlight,[1] against a neutral background (usually white, sometimes black).

Test screenings were held at the Gasthaus Sello in July 1895, attended by some invited friends and colleagues. The directors of the

After finishing the Wintergarten run of shows, the Bioskop opened in the

Max had constructed a new camera with a Geneva drive in the autumn of 1895,[3] and the new single-lens Bioskop-II projector in the summer of 1896.[1] They also recorded new films (on 63mm-wide celluloid), much needed since the old ones started to get damaged, including the fiction film Komische Begegnung im Tiergarten zu Stockholm (Comical Encounter in

After this Skladanowsky returned to his former photographic activities including the production of

Legacy

Between the years 1895 and 1905, the brothers directed at least 25 to 30 short movies.[5] In 1995, the German filmmaker Wim Wenders directed a drama documentary film Die Gebrüder Skladanowsky in collaboration with students of the Munich Academy for Television and Film in which Max Skladanowsky was played by Udo Kier.[6]

Trivia

In the Netherlands and the Balkans the word "bioscop" means cinema.[7]

Filmography

- 1895 : Bauerntanz zweier Kinder

- 1895 : Komisches Reck

- 1895 : Die Serpentintänzerin

- 1895 : Jongleur

- 1895 : Das Boxende Känguruh

- 1895 : Akrobatisches Potpourri

- 1895 : Kamarinskaja

- 1895 : Ringkämpfer

- 1895 : Apotheose

- 1896 : Unter den Linden

- 1896 : Nicht mehr allein

- 1896 : Mit Ablösung der Wache

- 1896 : Lustige Gesellschaft vor dem Tivoli in Kopenhagen

- 1896 : Leben und Treiben am Alexanderplatz

- 1896 : Komische Begenung im Tiergarten zu Stockholm

- 1896 : Ausfahrt nach dem Alarm

- 1896 : Ankunft eines Eisenbahnzuges

- 1896 : Alarm der Feuerwehr

- 1896 : Die Wachtparade

- 1897 : Am Bollwerk in Stettin

- 1897 : Apotheose II

- 1897 : Am Bollwerk

- 1900 : Eine Moderne Jungfrau von Orleans

- 1905 : Eine Fliegenjagd oder Die Rache der Frau Schultze

See also

- List of film formats

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Barber, Stephen (2010-10-11). "The Skladanowsky Brothers: The Devil Knows". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- ^ "Bundesarchiv - Bilddatenbank". Archived from the original on 2021-10-26.

- ^ a b c "Who's Who of Victorian Cinema". www.victorian-cinema.net. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- ^ Komische Begegnung im Tiergarten zu Stockholm (1896) - IMDb, retrieved 2020-03-22

- ^ IMDB entry

- IMDb

- ^ recnik.krstarica.com

- Max Skladanowsky at Who's Who of Victorian Cinema

- Castan, Joachim. Max Skladanowsky oder der Beginn einer deutschen Filmgeschichte, Stuttgart, 1995. ISBN 3-9803451-3-0. Standard work about Skladanowsky - exciting and profound. It's a pity that there's no English translation.

External links

- Max Skladanowsky at IMDb

- Emil Skladanowsky at IMDb

- Eugen Skladanowsky at IMDb

- Newspaper clippings about Max Skladanowsky in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW