Crustacean

| Crustaceans | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Clade: | Pancrustacea |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Groups included | |

| |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

Crustaceans are a group of

The 67,000 described species range in size from

Most crustaceans are free-living

Structure

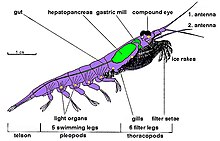

The body of a crustacean is composed of segments, which are grouped into three regions: the cephalon or head,[5] the pereon or thorax,[6] and the pleon or abdomen.[7] The head and thorax may be fused together to form a cephalothorax,[8] which may be covered by a single large carapace.[9] The crustacean body is protected by the hard exoskeleton, which must be moulted for the animal to grow. The shell around each somite can be divided into a dorsal tergum, ventral sternum and a lateral pleuron. Various parts of the exoskeleton may be fused together.[10]: 289

Each

Crustacean

The main body cavity is an

In many decapods, the first (and sometimes the second) pair of pleopods are specialised in the male for sperm transfer. Many terrestrial crustaceans (such as the Christmas Island red crab) mate seasonally and return to the sea to release the eggs. Others, such as woodlice, lay their eggs on land, albeit in damp conditions. In most decapods, the females retain the eggs until they hatch into free-swimming larvae.[22]

Ecology

Most crustaceans are aquatic, living in either marine or

Life cycle

Mating system

Most crustaceans have

Eggs

In many crustaceans, the fertilised eggs are released into the

Larvae

Crustaceans exhibit a number of larval forms, of which the earliest and most characteristic is the

Providing camouflage against predators, the otherwise black eyes in several forms of swimming larvae are covered by a thin layer of crystalline isoxanthopterin that gives their eyes the same color as the surrounding water, while tiny holes in the layer allow light to reach the retina.[37] As the larvae mature into adults, the layer migrates to a new position behind the retina where it works as a backscattering mirror that increases the intensity of light passing through the eyes, as seen in many nocturnal animals.[38]

DNA repair

In an effort to understand whether DNA repair processes can protect crustaceans against DNA damage, basic research was conducted to elucidate the repair mechanisms used by Penaeus monodon (black tiger shrimp).[39] Repair of DNA double-strand breaks was found to be predominantly carried out by accurate homologous recombinational repair. Another, less accurate process, microhomology-mediated end joining, is also used to repair such breaks. The expression pattern of DNA repair related and DNA damage response genes in the intertidal copepod Tigriopus japonicus was analyzed after ultraviolet irradiation.[40] This study revealed increased expression of proteins associated with the DNA repair processes of non-homologous end joining, homologous recombination, base excision repair and DNA mismatch repair.

Classification and phylogeny

The name "crustacean" dates from the earliest works to describe the animals, including those of Pierre Belon and Guillaume Rondelet, but the name was not used by some later authors, including Carl Linnaeus, who included crustaceans among the "Aptera" in his Systema Naturae.[41] The earliest nomenclatural valid work to use the name "Crustacea" was Morten Thrane Brünnich's Zoologiæ Fundamenta in 1772,[42] although he also included chelicerates in the group.[41]

The subphylum Crustacea comprises almost 67,000 described

The exact relationships of the Crustacea to other taxa are not completely settled as of April 2012[update]. Studies based on morphology led to the

The traditional classification of Crustacea based on morphology recognised four to six classes.[50] Bowman and Abele (1982) recognised 652 extant families and 38 orders, organised into six classes: Branchiopoda, Remipedia, Cephalocarida,

| Class | Members | Orders | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

Ostracoda |

Seed shrimp |

Platycopida Podocopida |

Cylindroleberididae (Myodocopida) |

Mystacocarida |

Mystococaridans |

Mystococarida |

Ctenocheilocaris galvarini |

Branchiura and Pentastomida may be recognised as classes) |

fish lice |

Reighardiida Arguloida |

Armillifer armillatus (Porocephalida) |

| Thecostraca | Barnacles |

Cryptophialida Lithoglyptida etc. |

Cirripedia )

|

Copepoda |

Copepods | etc. |

Cylindroleberididae (Calanoida) |

| Tantulocarida | Tantulocaridians |  Microdajus sp. | |

| Malacostraca | Hooded shrimp Amphipods etc. |

etc. |

Ocypode ceratophthalma )

(Decapoda |

| Cephalocarida | Horseshoe shrimp |

Brachypoda |

Hutchinsoniella macracantha

|

| Branchiopoda | Tadpole shrimp Clam shrimp |

Spinicaudata etc. |

Lepidurus arcticus (Notostraca) |

| Remipedia | Remipedes | Nectiopoda †Enantiopoda |

Speleonectes tanumekes |

| Hexapoda | Springtails Proturans Diplurans Insects |

etc. |

Mantispa styriaca (Neuroptera) |

The following cladogram shows the updated relationships between the different extant groups of the paraphyletic Crustacea in relation to the class Hexapoda.[53]

| Pancrustacea | Crustacea | |

According to this diagram, the Hexapoda are deep in the Crustacea tree, and any of the Hexapoda is distinctly closer to e.g. a Multicrustacean than an Oligostracan is.

Fossil record

Crustaceans have a rich and extensive

Within the Malacostraca, no fossils are known for

However, the great radiation of crustaceans occurred in the

Consumption by humans

Many crustaceans are consumed by humans, and nearly 10,700,000

See also

References

- ^ Calman, William Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 552.

- PMID 20624745.

- PMID 19854296.

- ^ "The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018 – Meeting the sustainable development goals" (PDF). fao.org. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2018.

- ^ a b "Cephalon". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ a b "Thorax". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ a b "Abdomen". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Cephalothorax". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Carapace". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ISBN 978-0-19-854055-7. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- S2CID 248430846.

- ^ Morphology of the brain in Hutchinsoniella macracantha (Cephalocarida, Crustacea) – page 290

- ^ "Telson". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- S2CID 83148200.

- ^ "Antennule". Crustacean Glossary. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Archived from the original on 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Crustaceamorpha: appendages". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- PMID 21680423.

- ^ Akira Sakurai. "Closed and Open Circulatory System". Georgia State University. Archived from the original on 2016-09-17. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ISBN 978-3-540-57420-0.

- ^ H. J. Ceccaldi. Anatomy and physiology of digestive tract of Crustaceans Decapods reared in aquaculture (PDF). AQUACOP, IFREMER. Actes de Colloque 9. pp. 243–259.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)[permanent dead link] - ^ Ghiselin, Michael T. (2005). "Crustacean". Encarta. Microsoft.

- ^ Burkenroad, M. D. (1963). "The evolution of the Eucarida (Crustacea, Eumalacostraca), in relation to the fossil record". Tulane Studies in Geology. 2 (1): 1–17.

- ^ "Crabs, lobsters, prawns and other crustaceans". Australian Museum. January 5, 2010. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Benthic animals". Icelandic Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture. Archived from the original on 2014-05-11. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ISBN 978-0-12-690645-5. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ISBN 978-0-521-48033-8. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- Invasive Species Specialist Group. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2017-12-24. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ISBN 978-90-04-11387-9. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ISBN 92-990003-2-8.

- ^ a b c d "Crustacean (arthropod)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 May 2023.

- ^ G. L. Pesce. "Remipedia Yager, 1981".

- ^ a b D. E. Aiken; V. Tunnicliffe; C. T. Shih; L. D. Delorme. "Crustacean". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ISBN 978-0-12-690647-9. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Zoea". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Calman, William Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 356.

- S2CID 54759780. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-07-17.

- ^ Shavit, Keshet, et al, A tunable reflector enabling crustaceans to see but not be seen, Science, February 16, 2023, and published in volume 379, issue 6633, February 17, 2023

- ^ Duff, Meg (February 16, 2023). ""Disco Eye-Glitter" Makes Baby Crustaceans Invisible". Slate – via slate.com.

- PMID 28431013.

- PMID 22051804.

- ^ ]

- ^ M. T. Brünnich (1772). Zoologiæ fundamenta prælectionibus academicis accomodata. Grunde i Dyrelaeren (in Latin and Danish). Copenhagen & Leipzig: Fridericus Christianus Pelt. pp. 1–254.

- ^ Zhi-Qiang Zhang (2011). Z.-Q. Zhang (ed.). "Animal biodiversity: an outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness - Phylum Arthropoda von Siebold, 1848" (PDF). Zootaxa. 4138: 99–103.

- Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ "Japanese Spider Crabs Arrive at Aquarium". Oregon Coast Aquarium. Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- PMID 19324730.

- S2CID 84906139.

- S2CID 4427443.

- PMID 22049065.

- ^ a b Joel W. Martin; George E. Davis (2001). An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea (PDF). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. pp. 1–132. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-12. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- .

- PMID 22977117.

- ^ PMID 28602656.

- PMID 31270537.

- PMID 37552897.

- ISBN 9781605353753.

- ISBN 978-0-6911-7025-1. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Fossil Record". Fossil Groups: Crustacea. University of Bristol. Archived from the original on 2016-09-07. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ .

- University College, London. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ISBN 978-3-540-90957-6.

- .

- ^ "Antarctic Prehistory". Australian Antarctic Division. July 29, 2008. Archived from the original on September 30, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- .

- .

- S2CID 31851291.

- .

- ^ Crean, Robert P. D. (November 14, 2004). "Dendrobranchiata". Order Decapoda. University of Bristol. Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- S2CID 129330859.

- S2CID 53067015.

- ^ .

- . Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- S2CID 131067067.

- ^ a b c "FIGIS: Global Production Statistics 1950–2007". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ISBN 978-92-5-104012-6.

Sources

- ISBN 978-0-19-503742-5.

- Powers, M., Hill, G., Weaver, R., & Goymann, W. (2020). An experimental test of mate choice for red carotenoid coloration in the marine copepod Tigriopus californicus. Ethology., 126(3), 344–352. An experimental test of mate choice for red carotenoid coloration in the marine copepod Tigriopus californicus

External links

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Encyclopedia Americana - Wikipedia". Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 8. 1920.

- New International Encyclopedia. Vol. 5.

- Crustacea.net, an online resource on the biology of crustaceans

- Crustacea Archived October 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

- Crustacea: Tree of Life Web Project

- The Crustacean Society Archived 2011-11-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Natural History Collections: Crustacea: University of Edinburgh

- Crustaceans (Crustacea) on the shore of Singapore

- Crustacea(crabs, lobsters, shrimps, prawns, barnacles) Archived 2012-01-11 at the Wayback Machine: Biodiversity Explorer