Medicinal plants

Medicinal plants, also called medicinal herbs, have been discovered and used in

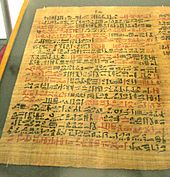

The earliest historical records of herbs are found from the Sumerian civilization, where hundreds of medicinal plants including opium are listed on clay tablets, c. 3000 BC. The Ebers Papyrus from ancient Egypt, c. 1550 BC, describes over 850 plant medicines. The Greek physician Dioscorides, who worked in the Roman army, documented over 1000 recipes for medicines using over 600 medicinal plants in De materia medica, c. 60 AD; this formed the basis of pharmacopoeias for some 1500 years. Drug research sometimes makes use of ethnobotany to search for pharmacologically active substances, and this approach has yielded hundreds of useful compounds. These include the common drugs aspirin, digoxin, quinine, and opium. The compounds found in plants are diverse, with most in four biochemical classes: alkaloids, glycosides, polyphenols, and terpenes. Few of these are scientifically confirmed as medicines or used in conventional medicine.

Medicinal plants are widely used as folk medicine in non-industrialized societies, mainly because they are readily available and cheaper than modern medicines. The annual global export value of the thousands of types of plants with medicinal properties was estimated to be US$60 billion per year and growing at the rate of 6% per annum.[citation needed] In many countries, there is little regulation of traditional medicine, but the World Health Organization coordinates a network to encourage safe and rational use. The botanical herbal market has been criticized for being poorly regulated and containing placebo and pseudoscience products with no scientific research to support their medical claims.[3] Medicinal plants face both general threats, such as climate change and habitat destruction, and the specific threat of over-collection to meet market demand.[3]

History

Prehistoric times

Plants, including many now used as

Ancient times

In ancient

From ancient times to the present,

Middle Ages

In the

Early Modern

The

19th and 20th centuries

The place of plants in medicine was radically altered in the 19th century by the application of

Context

Medicinal plants are used with the intention of maintaining health, to be administered for a specific condition, or both, whether in modern medicine or in traditional medicine.[3][36] The Food and Agriculture Organization estimated in 2002 that over 50,000 medicinal plants are used across the world.[37] The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew more conservatively estimated in 2016 that 17,810 plant species have a medicinal use, out of some 30,000 plants for which a use of any kind is documented.[38]

In modern medicine, around a quarter[a] of the drugs prescribed to patients are derived from medicinal plants, and they are rigorously tested.[36][39] In other systems of medicine, medicinal plants may constitute the majority of what are often informal attempted treatments, not tested scientifically.[40] The World Health Organization estimates, without reliable data, that some 80 percent of the world's population depends mainly on traditional medicine (including but not limited to plants); perhaps some two billion people are largely reliant on medicinal plants.[36][39] The use of plant-based materials including herbal or natural health products with supposed health benefits, is increasing in developed countries.[41] This brings attendant risks of toxicity and other effects on human health, despite the safe image of herbal remedies.[41] Herbal medicines have been in use since long before modern medicine existed; there was and often still is little or no knowledge of the pharmacological basis of their actions, if any, or of their safety. The World Health Organization formulated a policy on traditional medicine in 1991, and since then has published guidelines for them, with a series of monographs on widely used herbal medicines.[42][43]

Medicinal plants may provide three main kinds of benefit: health benefits to the people who consume them as medicines; financial benefits to people who harvest, process, and distribute them for sale; and society-wide benefits, such as job opportunities, taxation income, and a healthier labour force.[36] However, development of plants or extracts having potential medicinal uses is blunted by weak scientific evidence, poor practices in the process of drug development, and insufficient financing.[3]

Phytochemical basis

All plants produce chemical compounds which give them an

Modern knowledge of medicinal plants is being systematised in the Medicinal Plant Transcriptomics Database, which by 2011 provided a sequence reference for the transcriptome of some thirty species.[49] Major classes of plant phytochemicals are described below, with examples of plants that contain them.[8][43][50][51][52]

Alkaloids

-

The alkaloid nicotine from tobacco binds directly to the body's Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, accounting for its pharmacological effects.[58]

-

Deadly nightshade, Atropa belladonna, yields tropane alkaloids including atropine, scopolamine and hyoscyamine.[54]

Glycosides

The

-

Thefoxglove, Digitalis purpurea, contains digoxin, a cardiac glycoside. The plant was used on heart conditions long before the glycoside was identified.[44][63]

Polyphenols

Many polyphenolic extracts, such as from

-

Angelica, containing phytoestrogens, has long been used for gynaecological disorders.

Terpenes

-

Theantifungal.[76]

In practice

Cultivation

Medicinal plants demand intensive management. Different species each require their own distinct conditions of cultivation. The World Health Organization recommends the use of rotation to minimise problems with pests and plant diseases. Cultivation may be traditional or may make use of conservation agriculture practices to maintain organic matter in the soil and to conserve water, for example with no-till farming systems.[77] In many medicinal and aromatic plants, plant characteristics vary widely with soil type and cropping strategy, so care is required to obtain satisfactory yields.[78]

Preparation

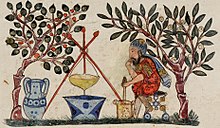

Medicinal plants are often tough and fibrous, requiring some form of preparation to make them convenient to administer. According to the Institute for Traditional Medicine, common methods for the preparation of herbal medicines include decoction, powdering, and extraction with alcohol, in each case yielding a mixture of substances. Decoction involves crushing and then boiling the plant material in water to produce a liquid extract that can be taken orally or applied topically.[79] Powdering involves drying the plant material and then crushing it to yield a powder that can be compressed into tablets. Alcohol extraction involves soaking the plant material in cold wine or distilled spirit to form a tincture.[80]

Traditional poultices were made by boiling medicinal plants, wrapping them in a cloth, and applying the resulting parcel externally to the affected part of the body.[81]

When modern medicine has identified a drug in a medicinal plant, commercial quantities of the drug may either be synthesised or extracted from plant material, yielding a pure chemical.[33] Extraction can be practical when the compound in question is complex.[82]

Usage

Plant medicines are in wide use around the world.

Drugs derived from plants including opiates, cocaine and cannabis have both medical and

Effectiveness

Plant medicines have often not been tested systematically, but have come into use informally over the centuries. By 2007, clinical trials had demonstrated potentially useful activity in nearly 16% of herbal extracts; there was limited in vitro or in vivo evidence for roughly half the extracts; there was only phytochemical evidence for around 20%; 0.5% were allergenic or toxic; and some 12% had basically never been studied scientifically.[43] Cancer Research UK caution that there is no reliable evidence for the effectiveness of herbal remedies for cancer.[91]

A 2012

Regulation

The World Health Organization (WHO) has been coordinating a network called the International Regulatory Cooperation for Herbal Medicines to try to improve the quality of medical products made from medicinal plants and the claims made for them.

WHO has set out a strategy for traditional medicines[95] with four objectives: to integrate them as policy into national healthcare systems; to provide knowledge and guidance on their safety, efficacy, and quality; to increase their availability and affordability; and to promote their rational, therapeutically sound usage.[95] WHO notes in the strategy that countries are experiencing seven challenges to such implementation, namely in developing and enforcing policy; in integration; in safety and quality, especially in assessment of products and qualification of practitioners; in controlling advertising; in research and development; in education and training; and in the sharing of information.[95]

Drug discovery

The

Hundreds of compounds have been identified using

The pharmaceutical industry has remained interested in mining traditional uses of medicinal plants in its drug discovery efforts.[33] Of the 1073 small-molecule drugs approved in the period 1981 to 2010, over half were either directly derived from or inspired by natural substances.[33][102] Among cancer treatments, of 185 small-molecule drugs approved in the period from 1981 to 2019, 65% were derived from or inspired by natural substances.[103]

Safety

Plant medicines can cause adverse effects and even death, whether by side-effects of their active substances, by adulteration or contamination, by overdose, or by inappropriate prescription. Many such effects are known, while others remain to be explored scientifically. There is no reason to presume that because a product comes from nature it must be safe: the existence of powerful natural poisons like atropine and nicotine shows this to be untrue. Further, the high standards applied to conventional medicines do not always apply to plant medicines, and dose can vary widely depending on the growth conditions of plants: older plants may be much more toxic than young ones, for instance.[105][106][107][108][109][110]

Plant extracts may interact with conventional drugs, both because they may provide an increased dose of similar compounds, and because some phytochemicals interfere with the body's systems that metabolise drugs in the liver including the cytochrome P450 system, making the drugs last longer in the body and have a cumulative effect.[111] Plant medicines can be dangerous during pregnancy.[112] Since plants may contain many different substances, plant extracts may have complex effects on the human body.[5]

Quality, advertising, and labelling

Herbal medicine and

Threats

Where medicinal plants are harvested from the wild rather than cultivated, they are subject to both general and specific threats. General threats include climate change and habitat loss to development and agriculture. A specific threat is over-collection to meet rising demand for medicines.[121] A case in point was the pressure on wild populations of the Pacific yew soon after news of taxol's effectiveness became public.[33] The threat from over-collection could be addressed by cultivation of some medicinal plants, or by a system of certification to make wild harvesting sustainable.[121] A report in 2020 by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew identifies 723 medicinal plants as being at risk of extinction, caused partly by over-collection.[122][103]

See also

- Australian Phytochemical Survey

- Ethnomedicine

- European Directive on Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products

- Plant Resources of Tropical Africa

Notes

- ^ Farnsworth states that this figure was based on prescriptions from American community pharmacies between 1959 and 1980.[39]

- ^ Berberine is the main active component of an ancient Chinese herb Coptis chinensis French, which has been administered for what Yin and colleagues state is "diabetes" for thousands of years, although with no sound evidence of efficacy.[55]

- ^ Tobacco has "probably been responsible for more deaths than any other herb", but it was used as a medicine in the societies encountered by Columbus and was considered a panacea in Europe. It is no longer accepted as medicinal.[56]

References

- PMC 535471.

- PMID 35084361.

- ^ PMID 27998396.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8020-8313-5.

- ^ from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- S2CID 22420170.

- PMID 11384883.

- ^ a b "Angiosperms: Division Magnoliophyta: General Features". Encyclopædia Britannica (volume 13, 15th edition). 1993. p. 609.

- PMID 15137997.

- PMID 11282438.

- ISBN 978-0-88192-483-1.

- S2CID 71625677.

- S2CID 40027370.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-88192-483-1.

- ^ Petrovska 2012, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Dwivedi G, Dwivedi S (2007). History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence (PDF). National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-88192-483-1.

- ISBN 978-0-19-514017-0.

- ISBN 978-0-521-64380-1.

- ISBN 978-0-415-93849-5.

- ISBN 978-1-57958-090-2.

- S2CID 13404562.

- ISBN 978-0-415-02063-3.

- ISBN 978-1-57954-304-4.

- .

- PMID 10386051.

- S2CID 162374182.

- S2CID 45980791.

- ^ The Edinburgh Review. 237: 95–112.

- JSTOR 25703506.

- ^ Heywood VH (2012). "The role of New World biodiversity in the transformation of Mediterranean landscapes and culture" (PDF). Bocconea. 24: 69–93. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-27. Retrieved 2017-02-26.

- S2CID 46457797.

- ^ PMID 26281720.

- PMID 22654398.

- from the original on 2022-01-21, retrieved 2022-04-02

- ^ PMID 23148504.

- ^ Schippmann U, Leaman DJ, Cunningham AB (12 October 2002). "Impact of Cultivation and Gathering of Medicinal Plants on Biodiversity: Global Trends and Issues 2. Some Figures to start with ..." Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Satellite event on the occasion of the Ninth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Rome, 12–13 October 2002. Inter-Departmental Working Group on Biological Diversity for Food and Agriculture. Rome. Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ "State of the World's Plants Report - 2016" (PDF). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ PMID 3879679.

- PMID 18797616. Archived from the originalon January 24, 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ PMID 24454289.

- ISBN 978-1-4987-5096-7.

- ^ S2CID 29427595.

- ^ a b c d e "Active Plant Ingredients Used for Medicinal Purposes". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

Below are several examples of active plant ingredients that provide medicinal plant uses for humans.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-5183-8.

- PMID 17133715.

- ^ "Galantamine". Drugs.com. 2017. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- PMID 16437532.

- ^ Soejarto DD (1 March 2011). "Transcriptome Characterization, Sequencing, And Assembly Of Medicinal Plants Relevant To Human Health". University of Illinois at Chicago. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-58716-083-7.

- ISBN 978-0-387-85497-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Elumalai A, Eswariah MC (2012). "Herbalism - A Review" (PDF). International Journal of Phytotherapy. 2 (2): 96–105. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-17. Retrieved 2017-02-17.

- ISBN 978-0-444-52736-3.

- ^ a b "Atropa Belladonna" (PDF). The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- PMID 18442638.

- PMID 15173337.

- S2CID 25434984.

- ^ "Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Introduction". IUPHAR Database. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- PMID 24160332.

- ISBN 978-0-444-53294-7.

- ^ PMID 3671329.

- ^ Akolkar, Praful (2012-12-27). "Pharmacognosy of Rhubarb". PharmaXChange.info. Archived from the original on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- ^ "Digitalis purpurea. Cardiac Glycoside". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

The man credited with the introduction of digitalis into the practice of medicine was William Withering.

- PMID 24319081.

- ISBN 978-0-521-36377-8.

- from the original on 2019-04-19. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- PMID 16915857.

- ISBN 978-981-02-2773-9.

- PMID 6999244.

- ^ .

- ISBN 978-81-7387-162-7.

- PMID 17518366.

- ISBN 978-0-12-398373-2.

- JSTOR 27836252.

- JSTOR 2588737.

- ^ a b c "Thymol (CID=6989)". NIH. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

THYMOL is a phenol obtained from thyme oil or other volatile oils used as a stabilizer in pharmaceutical preparations, and as an antiseptic (antibacterial or antifungal) agent. It was formerly used as a vermifuge.

- ^ "WHO Guidelines on Good Agricultural and Collection Practices (GACP) for Medicinal Plants". World Health Organization. 2003. Archived from the original on October 20, 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- PMID 22419102.

- ISBN 9780702031328. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Dharmananda S (May 1997). "The Methods of Preparation of Herb Formulas: Decoctions, Dried Decoctions, Powders, Pills, Tablets, and Tinctures". Institute of Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon. Archived from the original on 2017-10-04. Retrieved 2017-09-27.

- ^ Mount T (20 April 2015). "9 weird medieval medicines". British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- PMID 9037244.

- ^ "Traditional Medicine. Fact Sheet No. 134". World Health Organization. May 2003. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ a b Chan M (19 August 2015). "WHO Director-General addresses traditional medicine forum". WHO. Archived from the original on August 22, 2015.

- ^ "Traditional Chinese Medicine: In Depth (D428)". NIH. April 2009. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Giovannini P. "Managing diabetes with medicinal plants". Kew Gardens. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- from the original on 2022-06-07. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- ^ Milliken W (2015). "Medicinal knowledge in the Amazon". Kew Gardens. Archived from the original on 2017-10-03. Retrieved 2017-10-03.

- ^ Yanomami, M. I., Yanomami, E., Albert, B., Milliken, W, Coelho, V. (2014). Hwërɨ mamotima thëpë ã oni. Manual dos remedios tradicionais Yanomami [Manual of Traditional Yanomami Medicines]. São Paulo: Hutukara/Instituto Socioambiental.

- ^ "Scoring drugs. A new study suggests alcohol is more harmful than heroin or crack". The Economist. 2 November 2010. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

"Drug harms in the UK: a multi-criteria decision analysis", by David Nutt, Leslie King and Lawrence Phillips, on behalf of the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs. The Lancet.

- ^ "Herbal medicine". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

There is no reliable evidence from human studies that herbal remedies can treat, prevent or cure any type of cancer. Some clinical trials seem to show that certain Chinese herbs may help people to live longer, might reduce side effects, and help to prevent cancer from coming back. This is especially when combined with conventional treatment.

- ^ PMID 22984175.

- ^ "International Regulatory Cooperation for Herbal Medicines (IRCH)". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- JSTOR 24099124.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-4-150609-0. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2017-11-18. Retrieved 2017-10-03.

- ^ "Emergence of Pharmaceutical Science and Industry: 1870-1930". Chemical & Engineering News. Vol. 83, no. 25. 20 June 2005. Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- PMID 16515525.

- PMID 24404355.

- PMID 11250806.

- PMID 25254460.

- PMID 25163000.

- PMID 22316239.

- ^ a b "State of the World's Plants and Fungi 2020" (PDF). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ISBN 978-90-481-2447-3.

- PMID 9528737. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2019-11-05. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- PMID 11242573.

- PMID 11297844.

- PMID 17761132.

- PMID 17913230.

- PMID 11759460.

- PMID 17969314.

- S2CID 35882289.

- ^ Barrett, Stephen (23 November 2013). "The herbal minefield". Quackwatch. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- PMID 22305255.

- PMID 13129992.

- PMID 22511890.

- PMID 24120035.

- ^ O'Connor A (5 November 2013). "Herbal Supplements Are Often Not What They Seem". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- PMID 34513589.

- ^ "United States Files Enforcement Action to Stop Deceptive Marketing of Herbal Tea Product Advertised as Covid-19 Treatment". United States Department of Justice. Department of Justice. 3 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ S2CID 7246069.

- ^ Briggs H (30 September 2020). "Two-fifths of plants at risk of extinction, says report". BBC. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

![The opium poppy Papaver somniferum is the source of the alkaloids morphine and codeine.[52]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Opium_poppy.jpg/160px-Opium_poppy.jpg)

![The alkaloid nicotine from tobacco binds directly to the body's Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, accounting for its pharmacological effects.[58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/70/Nicotine.svg/143px-Nicotine.svg.png)

![Deadly nightshade, Atropa belladonna, yields tropane alkaloids including atropine, scopolamine and hyoscyamine.[54]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b7/Atropa_belladonna_-_K%C3%B6hler%E2%80%93s_Medizinal-Pflanzen-018.jpg/104px-Atropa_belladonna_-_K%C3%B6hler%E2%80%93s_Medizinal-Pflanzen-018.jpg)

![Senna alexandrina, containing anthraquinone glycosides, has been used as a laxative for millennia.[61]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/61/Senna_alexandrina_Mill.-Cassia_angustifolia_L._%28Senna_Plant%29.jpg/161px-Senna_alexandrina_Mill.-Cassia_angustifolia_L._%28Senna_Plant%29.jpg)

![The foxglove, Digitalis purpurea, contains digoxin, a cardiac glycoside. The plant was used on heart conditions long before the glycoside was identified.[44][63]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/Digitalis_purpurea2.jpg/90px-Digitalis_purpurea2.jpg)

![Digoxin is used to treat atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter and sometimes heart failure.[44]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4d/Digoxin.svg/200px-Digoxin.svg.png)

![Polyphenols include phytoestrogens (top and middle), mimics of animal estrogen (bottom).[72]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/Phytoestrogens2.png/160px-Phytoestrogens2.png)

![The essential oil of common thyme (Thymus vulgaris), contains the monoterpene thymol, an antiseptic and antifungal.[76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/Thymian.jpg/181px-Thymian.jpg)

![Thymol is one of many terpenes found in plants.[76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Thymol2.svg/97px-Thymol2.svg.png)