Mediterranean and Middle East theatre of World War II

| Mediterranean and Middle East theatre | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second World War | |||||||||

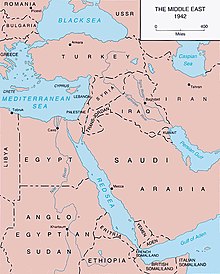

A map of the Mediterranean in 1941 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

The Mediterranean and Middle East Theatre was a major

The British referred to this theatre as the Mediterranean and Middle East Theatre (so called due to the location of the fighting and the name of Middle East Command), the Americans called it the Mediterranean Theater of War and the German informal official history of the fighting is the Mediterranean, South-East Europe, and North Africa 1939–1941. Despite the large size of the theatre, the various campaigns were not seen as neatly separated areas of operations but part of a vast, contiguous theatre of war.

Fascist Italy aimed to

The Mediterranean and Middle East theatre had the longest duration of the World War II, resulted in the destruction of the Italian Empire, and severely undermined the strategic position of Germany, resulting in German divisions being deployed to Africa and Italy and total German losses (including those captured upon final surrender) being over two million.[d] Italian losses amounted to around 177,000 men with a further several hundred thousand captured during the process of the various campaigns. British losses amount to over 300,000 men killed, wounded, or captured, and total American losses in the region amounted to 130,000.

Background

Legend:

Italy

During the late 1920s,

On 30 November 1938, Mussolini addressed the

Mussolini lauded the conquest as a new source of raw materials and location for emigration and speculated that a native army could be raised there to "help conquer the Sudan.[11] "Almost as soon as the Abyssinian campaign ended, Italian intervention in the Spanish Civil War" began.[12] On 7 April 1939, Mussolini began the Italian invasion of Albania and within two days had occupied the country.[13] In May 1939, Italy formally allied to Nazi Germany in the Pact of Steel.[14]

Italian foreign policy went through two stages during the Fascist regime. Until 1934–35, Mussolini followed a "modest ... and responsible" course and following that date there was "ceaseless activity and aggression".[15] "Prior to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, Mussolini had made military agreements with the French and formed a coalition with the British and French to prevent German aggression in Europe." The Ethiopian War "exposed vulnerabilities and created opportunities that Mussolini seized to realise his imperial vision"[16]

Britain

At the Nyon Conference of 1937, Italy and the United Kingdom "disclaimed any desire to modify or see modified the national sovereignty of any country in the Mediterranean area, and agreed to discourage any activities liable to impair mutual relations."[17] Italian diplomatic and military moves did not reflect this agreement.[18] In the aftermath of the Italian invasion of Abyssinia, British and Italian forces in North Africa were reinforced.[19] Due to various Italian moves, in July 1937, the British decided "that Italy could not now be regarded as a reliable friend" and preparations began to bring "the defences of the Mediterranean and the Red Sea ports up-to-date".[18] In 1938, a weak armoured division was established in Egypt and further army and air force reinforcements were dispatched from Britain.[19][20]

With rising tension in Europe, in June 1939, the United Kingdom established Middle East Command (MEC) in Cairo to provide centralised command for British army units in the Mediterranean and Middle East theatre.[21] All three branches of the British military were made equally responsible for the defence of the area.[22] The authority of MEC included Aden, British Somaliland, Cyprus, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Greece, Libya, Palestine, Iraq, Sudan, Tanganyika, Transjordan, Uganda and the shores of the Persian Gulf.[23][24][25] If necessary, command would be exerted as far away as the Caucasus and the Indian Ocean. The purpose of the command was to be "the western bastion of defence of India", keep British supply lines open to India and the Far East, and keep the Middle Eastern oilfields out of Axis hands.[25]

Upon the establishment of MEC, it was ordered to co-ordinate with the French military in the Middle East and Africa as well as liaise with the

British forces in the Middle East were ordered to avoid provocation.

Initial military operations

On 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on France and the United Kingdom and next day the British Commonwealth declared war on Italy.

On 22 June, France signed an

When Italy entered the war, there were no plans for an

On 9 September, Italian aircraft start preparation bombardments for the invasion of Egypt. Four days later, Italian infantry attacked and advanced as far as

The Royal Navy inflicted a major setback upon the Italian Royal Navy during the

Axis success

North Africa

In North Africa, the Italians responded to the defeat of their Tenth Army by dispatching armour and motorised divisions.[52] Germany dispatched the Afrika Korps in Operation Sonnenblume, to bolster the Italians with a mission to block further Allied attempts to drive the Italians out of the region. Its commanding officer—Erwin Rommel—seized on the weakness of his opponents and without waiting for his forces to fully assemble, rapidly went on the offensive.[53][54] In March–April 1941, Rommel defeated the British forces facing him and forced the British and Commonwealth forces into retreat.[55]

The

East Africa

In

Balkans

In April 1941,

Following the Italian invasion on 28 October 1940, which is usually known as the

After moving through south-eastern Yugoslavia, the Germans had been able to turn the Allied flank, cutting off Greek units in the east of the country. Greek forces in central Macedonia were isolated from the Commonwealth forces moving up in an attempt stabilise the front, with the Germans then falling on the rear of the main Greek army facing the Italians in Macedonia. The German advance into Greece was made easier because the bulk of the Greek Army was engaged fighting the Italians on the Albanian front in the north of the country.[66]

The Greeks were forced to capitulate, ending resistance on the mainland by the end of the month.[67] Abandoning most of its equipment, the Commonwealth force retreated to the island of Crete. From 20 May, the Germans attacked the island by using paratroops to secure an air bridgehead despite suffering heavy casualties. They then flew in more troops and were able to capture the rest of the island by 1 June.[68] With their victory in the Battle of Crete the Germans had secured their southern flank and turned their attention towards the Soviet Union.[69]

Middle East operations

Iraq

When Italy entered the war the Iraqi government did not break off diplomatic relations, as they had done with Germany.

On 1 April, Rashid Ali, along with four senior Army and Air Force officers known as the "

Before the coup, Rashid Ali's supporters had been informed that Germany would recognise the independence of Iraq from the British Empire. There had also been discussions on war material being sent to support the Iraqis and other Arab factions in fighting the British.

On 30 April, the Iraqi Army surrounded and besieged RAF Habbaniya; the base had no operational aircraft but the RAF converted trainers to carry weapons and a battalion of infantry reinforcements was flown in. German and Italian aircraft supported the Iraqi army and British reinforcements were dispatched to Iraq from Transjordan and India. The larger but poorly trained Iraqi force was defeated and Baghdad and

Operation Exporter

In Operation Exporter, Australian,

Iran

Supplies to the

Mandatory Palestine

Operation Atlas was carried out by a special commando unit of the

Operation Mammoth

In 1943 a small team of German agents parachuted into Iraqi Kurdistan with the goal of covertly sabotaging Kirkuk oil fields and create a Kurdish uprising against the British with assistance from local Kurds who were seeking to create an independent Kurdistan. Further reinforcements of Nazis with weapons was supposed to be sent but the mission failed within days as the Nazi commandos landed 300 km away from their target destination and lost their weapons. They were soon arrested by the British and faced execution as spies, however they were released several years after World War II ended. Gottfried Müller, one of the Nazi parachuters, would later write and publish a book describing his experiences in Kurdistan named “Im brennenden Orient” ('The Burning Orient'), which was published in Germany in 1959.[84]

Gibraltar and Malta

Gibraltar commanded the entrance to the Mediterranean and had been a British fortress since the early 18th century. The territory provided a strongly defended harbour, from which ships could operate in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

The

Bombing and the naval blockade led to food and commodity shortages and rationing was imposed on the inhabitants. Luftwaffe reinforcements in the Mediterranean joined in the bombing but during a lull in early 1942, 61 Supermarine Spitfires were delivered, which very much improved the defensive situation, although food, ammunition, and fuel were still short.[85] Supply runs during lulls in the bombing kept Malta in being but many ships like SS Ohio were damaged too severely to leave. The defence of the island ensured that the Allies had an advantage in the fight to control the Mediterranean and as the garrison recovered from periods of intense bombing, aircraft, submarines and light surface ships resumed attacks on Axis supply ships, leading to fuel and supply shortages for the Axis forces in Libya.[85]

Allied reply

North Africa

During 1941, the British launched several offensives to push back the Axis forces in North Africa. Operation Brevity failed as did Operation Battleaxe but Operation Crusader, the third and larger offensive was launched at the end of the year. Over December 1941 into early 1942, Allied forces pushed the Italian-German forces back through Libya to roughly the limit of the previous Operation Compass advance. Taking advantage of the Allied position, German forces counter-attacked and pushed back the Allies to Gazala, west of Tobruk. As both sides prepared offensives, the Axis forces struck first and inflicted a big defeat upon the Allied forces during the Battle of Gazala.[88] The routed Allied forces retreated to Egypt where they made a stand at El Alamein.[89]

Following the First Battle of El Alamein, which had stalled the Axis advance into Egypt, British forces went onto the offensive in October.[89] The Second Battle of El Alamein marked a watershed in the Western Desert Campaign and turned the tide in the North African Campaign. It ended the Axis threat to Egypt, the Suez Canal and of gaining access to the Middle Eastern and Persian oil fields via North Africa. As the Eighth Army pushed west across the desert, capturing Libya, German forces occupied southern France and landed in Tunisia. On 8 November, Allied forces launched Operation Torch landing in various places across French North Africa. In December 1942, after a 101-day British blockade, French Somaliland fell to the Allies.[90]

US involvement

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, the United States joined the war.[91] On 8 November 1942, American forces entered combat in North Africa with Operation Torch, which "transformed the Mediterranean from a British to an Allied theater of war", "succeeding operations in the Mediterranean area proved far more extensive than intended. One undertaking was to lead to the next".[92]

After liberating French North Africa and clearing the enemy from the Italian colonies, the Allies sought to bring the entire French empire effectively into the war against the Axis powers. They reopened the Mediterranean route to the Middle East. They went on from Africa to liberate Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica. They caused Mussolini to topple from power, and they brought his successors to surrender. They drew more and more German military resources into a stubborn defence of the Italian peninsula, and helped the Yugoslavs to pin down within their spirited country thousands of Axis troops. Eventually, the Allies delivered a solid blow from southern France against the German forces which were opposing the Allied drive from the beaches of Normandy! They made Marseilles available for Allied use and they occupied northern Italy and Greece." Howe further notes that "Hitler had always accepted the principle that the Mediterranean was an area of paramount Italian interest just as, farther north, German interests were exclusive.[92]

Allied forces were placed under the command of a Supreme Allied Commander

Southern Europe

Italian campaign and Italian Civil War

Following the Allied victory in North Africa the Allies invaded Sicily in Operation Husky on 10 July 1943, with amphibious and airborne landings. The Germans were unable to prevent the Allied capture of the island but evacuated most of their troops and equipment to the mainland before the Allies entered Messina on 17 August.[94] On 25 July, the Italian government deposed Mussolini, the Italian leader, who was subsequently arrested. The new government announced that it would continue the war but secretly commenced negotiations with the Allies.[95]

The Allied invasion of Italy started when the British Eighth Army landed in the toe of Italy on 3 September 1943, in Operation Baytown. The Italian government signed the surrender the same day, believing they would be given time to make preparations against the anticipated German intervention. The Allies announced the Armistice of Cassibile on 8 September and German forces implemented plans to occupy the Italian peninsula. On 9 September, American and British forces of the US Fifth Army landed at Salerno in Operation Avalanche and more British airborne troops landed at Taranto in Operation Slapstick.[96] German forces which had escaped from Sicily were concentrated against Avalanche, while additional forces were brought in to occupy Rome and disarm the Italian Army in central and northern Italy.[97]

The Germans were unable to prevent the Italian fleet sailing to Malta, although the battleship Roma was sunk by the Luftwaffe on 9 September.[95] In the occupied areas of southern Europe and the Mediterranean, German forces rapidly disarmed and captured Italian troops, putting down any resistance they offered in Yugoslavia, southern France and Greece.[98] Meanwhile, on 16 September, a German airborne force led by Otto Skorzeny rescued Mussolini from the mountain resort in the Gran Sasso where he was being held. A puppet government headed by Mussolini was subsequently set up in northern Italy as the successor state to the former fascist government.[99]

The

As the campaign in Italy continued, the rough terrain prevented fast movement and proved ideal for defence, the Allies continued to push the Germans northwards through the rest of the year. The German prepared defensive line called the Winter Line (parts of which were called the Gustav Line) proved a major obstacle to the Allies at the end of 1943, halting the advance. Operation Shingle, an amphibious assault at Anzio behind the line was intended to break it, but did not have the desired effect. The line was eventually broken by frontal assault at the Fourth Battle of Monte Cassino in the spring of 1944 and Rome was captured in June.[105]

Following the fall of Rome, the

Dodecanese Campaign

The brief campaign in the Italian-held

Invasion of southern France

On 15 August 1944, in an effort to aid their operations in

Post-war conflicts

Trieste

At the end of the war in Europe, on 1 May 1945, troops of the 4th Army of the Yugoslavia and the Slovene 9th Corpus NLA occupied the town of Trieste. The Germans surrendered to the Allies which entered the town the following day. The Yugoslavs had to leave the town some days after.[110]

Greece

Allied forces which had been sent to Greece in October 1944 after the German withdrawal, were attacked by the leftist

Syria

In Syria, nationalist protests were on the rise at the continued occupation of the Levant by France in May 1945. French forces then tried to quell the protests but concern with heavy Syrian casualties forced Winston Churchill to oppose French action there. After being rebuffed by Charles De Gaulle he ordered British forces under general Bernard Paget into Syria from Jordan with orders to fire on the French if necessary. A crisis began as British armoured cars and troops then reached the Syrian capital Damascus following which the French were escorted and confined to their barracks. With political pressure added the French ordered a ceasefire; following which the French withdrew from Syria the following year.[112]

Palestine

Prior to the war, the British Mandate of Palestine was faced with

See also

- List of World War II battles

- Mediterranean U-boat Campaign (World War II)

- Military history of Gibraltar during World War II

- Timeline of the North African campaign

Notes

- ^ Participated in the Invasion of Yugoslavia.

- ^ Participated in Operation Achse.

- ^ Germany unconditionally surrendered on 8 May 1945 but Croatia still fought until the end of the Battle of Odžak on 23 May.

- Second World War, the Battle of the Atlantic was fought from 1939 to 1945, the war's longest continuous military campaign.[1][2]

Citations

- ^ Blair (1996), p. xiii

- ^ Woodman (2004), p. 1

- ^ a b Smith, p. 170

- ^ Martel, p. 184, 198

- ^ Bideleux and Jeffries, p. 467

- ^ a b Bell, p. 72

- ^ a b Salerno, pp. 105–106

- ^ Bell, pp. 72–73

- ^ Mallet, p. 9

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 21

- ^ Bell, p. 70

- ^ Beevor (2006). pp. 135–6.

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 24

- ^ Weinberg, p. 73

- ^ Bell, p. 76

- ^ Martel, pp. 178, 198

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 7

- ^ a b Playfair (1954), p. 8

- ^ a b Fraser, pp. 18–19

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 12

- ^ Playfair (1954), pp. 31–32, 459

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 33

- ^ Playfair (1954), pp. 31, 457

- ^ Bilgin, p.74

- ^ a b Fraser, p. 114

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 458

- ^ Playfair (1954), pp. 51, 53

- ^ Playfair (1954), pp. 24–25

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 41

- ^ Playfair (1954), pp. 48–49

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 54

- ^ Playfair (1954) p. 53

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 100

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 109

- ^ Wragg, p. 228.

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 112

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 118

- ^ a b c d e f Overy, pp. 56–57

- ^ Jowett, p. 5.

- ^ Bell, p. 306

- ^ Bulletin of International News, pp. 852–854

- ^ Rodogno, p. 9

- ^ Maier, p. 311

- ^ Weinberg, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Playfair (1954), p. 207

- ^ Macksey, p. 35

- ^ Playfair (1954), pp. 209–210

- ^ Carol, p. 12.

- ^ a b Weinberg, p. 210.

- ^ Playfair (1956), pp. 2–5

- ^ Martel (1994), p. 108.

- ^ Bauer, p.121

- ^ Jentz, p. 82

- ^ Rommel, p. 109

- ^ Playfair (1956), pp. 19–40

- ^ Latimer, pp. 43–45

- ^ Playfair (1956), pp. 33–35

- ^ Playfair (1956), p. 160

- ^ Jentz, pp. 128–129, 131

- ^ Weinberg, p. 211.

- ^ Fage, Crowder & Oliver, p. 461.

- ^ Cernuschi, 1994, pp. 5–74

- ^ a b Weinberg, p. 217.

- ^ Keegan, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Overy, pp. 68–71

- ^ Stockings & Hancock, pp. 78–82

- ^ Weinberg, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Keegan, pp. 129–139.

- ^ Playfair (1956), pp. 148–149.

- ISBN 978-0-7139-9712-5.

- ISBN 978-3-76375-923-1.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - OCLC 4025485.

- ^ Playfair (1956), p. 177

- ^ Churchill, p. 224

- ^ a b c Playfair (1956), p. 178

- ^ Lyman, p. 12

- ^ Lyman, p. 13

- ^ Lyman, p. 16

- ^ Lyman, p. 31

- ^ Lyman, p. 63

- ^ Playfair (1956), pp. 194–195

- ^ Churchill, p. 288

- ^ Fountain 2001.

- ^ "History of the Kurds". Kurdistan Memory Programme.

- ^ a b c d Sturgeon, pp. 180–181

- ^ "23rd Flotilla". Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ Blair (1996), pp. 395–404

- ^ Overy, pp. 120–121

- ^ a b Overy, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Overy, pp. 134–137.

- ^ Weinberg, pp. 260–263.

- ^ a b Howe, pp. 3–10

- ^ Overy, pp. 148–149

- ^ Keegan, pp. 288–290.

- ^ a b Keegan, p. 291.

- ^ Sturgeon, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Keegan, pp. 291–292.

- ^ Keegan, p. 292.

- ^ Keegan, pp. 292–293.

- ^ De Felice 1995, p. 22.

- ^ Storia della guerra civile in Italia

- ^ See the books from Italian historian Giorgio Pisanò Storia della guerra civile in Italia, 1943–1945, 3 voll., Milano, FPE, 1965 and the book L'Italia della guerra civile ("Italy of civil war"), published in 1983 by the Italian writer and journalist Indro Montanelli as the fifteen volume of the Storia d'Italia ("History of Italy") by the same author.

- ^ See as examples the interview to French historian Pierre Milza on the Corriere della Sera of 14 July 2005 (in Italian) and the lessons of historian Thomas Schlemmer at the University of Munchen (in German).

- ISBN 9781139499644.

- ^ a b c Clark, p. 3.

- ^ Clark, p. 1.

- ^ Ready (1985a)

- ^ Ready (1985b)

- ^ Corrigan (2011), p. 523

- ^ a b Sturgeon, pp. 304–305

- ^ Sturgeson, pp. 274–275

- ^ Luce, Henry Robinson (1945). Time, Volume 45. Time Incorporated. pp. 25–26.

References

Books

- Aly, Götz; Chase, Jefferson (2008). Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State. London: Picador. ISBN 978-0-8050-8726-0.

- Bauer, Eddy (2000) [1979]. Young, Peter (ed.). The History of World War II (rev. ed.). London: Orbis. ISBN 1-85605-552-3.

- Bell, P. M. H. (1997) [1986]. The Origins of the Second World War in Europe (2nd ed.). London: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-582-30470-3.

- ISBN 0-297-84832-1.

- Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (1998). A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16111-4.

- Bilgin, Pinar (2005). Regional Security in the Middle East. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32549-3.

- Blair, Clay (1996). Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunters 1939–1942. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-58839-8.

- Carol, Steven (2012). From Jerusalem to the Lion of Judah and Beyond: Israel's Foreign Policy in East Africa. Bloomington: IUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4697-6129-9.

- Clark, Lloyd (2008). Crossing the Rhine: Breaking into Nazi Germany, 1944 and 1945 – The Greatest Airborne Battles in History. New York, NY: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-0-87113-989-4.

- Corrigan, Gordon (2011). The Second World War: A Military History. London: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-57709-4.

- De Felice, Renzo (1995). Rosso e Nero [Red and Black] (in Italian). Baldini & Castoldi. ISBN 88-85987-95-8.

- Ehlers, Robert S. Jr. (2015). The Mediterranean Air War: Airpower and Allied Victory in World War II. Modern war studies. Lawrence, KN: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-70062-075-3.

- Fage, J. D.; Crowder, Michael; Oliver, Roland (1984). The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1940 to 1975. Vol. VIII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22409-3.

- Fraser, David (1999) [1983]. And We Shall Shock Them: The British Army in the Second World War. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 0-304-35233-0.

- Howe, George F. (1993) [1957]. Northwest Africa: Seizing the Initiative in the West. United States Army in World War II: The Mediterranean Theatre of Operations. Washington DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. OCLC 256063428. Archived from the originalon 28 May 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- Jentz, Thomas L. (1998). Tank Combat in North Africa: The Opening Rounds, Operations Sonnenblume, Brevity, Skorpion and Battleaxe, February 1941 – June 1941. New York: Schiffer. ISBN 0-7643-0226-4.

- Jowett, Philip (2000). Italian Army, 1940–1945. Vol. I. Osprey. ISBN 978-1-85532-864-8.

- Keegan, John (1997) [1989]. The Second World War. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-7348-2.

- Latimer, Jon (2001). Tobruk 1941: Rommel's Opening Move. Osprey. ISBN 0-275-98287-4.

- Mack Smith, Denis (1982). Mussolini. Littlehampton Book Services. ISBN 978-0-297-78005-2.

- OCLC 637460844.

- Mallett, Rovert (2003). Mussolini and the Origins of the Second World War, 1933–1940. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-74814-5.

- Maier, Klaus (1991). Germany's Initial Conquests in Europe. ISBN 978-0-19-822885-1.

- Martel, Gordon, ed. (1999). The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16325-5.

- Martel, André (1994). Histoire militaire de la France [Military History of France] (in French). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-046074-7.

- Overy, Richard (2014). Book of World War II. All About History. Imagine. ISBN 978-1910-155-295.

- ISBN 1-84574-065-3.

- Playfair, Major-General I. S. O.; with Flynn R. N., Captain F. C.; Molony, Brigadier C. J. C. & Toomer, Air Vice-Marshal S. E. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1956]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Germans Come to the Help of Their Ally (1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. II. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-84574-066-1.

- Ready, J. Lee (1985). Forgotten Allies: The Military Contribution of the Colonies, Exiled Governments and Lesser Powers to the Allied Victory in World War II: The European Theatre. Vol. I. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-89950-129-1.

- Ready, J. Lee (1985). Forgotten Allies: The Military Contribution of the Colonies, Exiled Governments and Lesser Powers to the Allied Victory in World War II: The Asian Theatre. Vol. II. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-89950-117-8.

- Rodogno, Davide (2006). Fascism's European Empire: Italian Occupation during the Second World War. New Studies in European History. trans. A. Belton. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84515-1.

- ISBN 0-306-80157-4.

- Salerno, Reynolds M. (2002). Vital Crossroads: Mediterranean Origins of the Second World War, 1935–1940. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3772-4.

- Stockings, C.; Hancock, E. (2013). Swastika over the Acropolis: Re-interpreting the Nazi Invasion of Greece in World War II. Boston: BRILL. ISBN 978-9-00425-459-6.

- Sturgeon, Alison (2009). World War II: The Definitive Visual History. New York, NY: Dorling Kimberly. ISBN 978-0-7566-4278-5.

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1994). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44317-3.

- Wragg, David (2003). Malta: The Last Great Siege 1940–1943. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-0-85052-990-6.

Journals

- "The Franco-Italian Armistice". Bulletin of International News. 17 (14). London: Royal Institute of International Affairs: 852–854. 13 July 1940. OCLC 300290398.

Websites

- Fountain, Rick (5 July 2001). "Nazis planned Palestine subversion". BBC News.

Further reading

- Cernuschi, Enrico (December 1994). "La resistenza sconosciuta in Africa Orientale" [The Unknown Resistance in East Africa]. Rivista Storica (in Italian). Rivista Italiana Difesa. OCLC 30747124. Retrieved 2 June 2015.