Medroxyprogesterone acetate

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /mɛˌdrɒksiproʊˈdʒɛstəroʊn ˈæsɪteɪt/ me-DROKS-ee-proh-JES-tər-ohn ASS-i-tayt[1] |

| Trade names | Depo-Provera, others |

| Other names | MPA; DMPA; Methylhydroxy |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604039 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

conjugates)[6] | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 207 to 209 °C (405 to 408 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), also known as depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) in

Common

MPA was discovered in 1956 and was introduced for medical use in the United States in 1959.

Medical uses

The most common use of MPA is in the form of DMPA as a long-acting

DMPA reduces

Though not used as a treatment for

Birth control

| Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) | |

|---|---|

POP ) allowing more reliable return fertility. |

DMPA, under brand names such as Depo-Provera and Depo-SubQ Provera 104, is used in

Effectiveness

Trussell's estimated perfect use first-year failure rate for DMPA as the average of failure rates in seven clinical trials at 0.3%.[40][41] It was considered perfect use because the clinical trials measured efficacy during actual use of DMPA defined as being no longer than 14 or 15 weeks after an injection (i.e., no more than 1 or 2 weeks late for a next injection).

Prior to 2004, Trussell's typical use failure rate for DMPA was the same as his perfect use failure rate: 0.3%.[42]

- DMPA estimated typical use first-year failure rate = 0.3% in:

In 2004, using the 1995 NSFG failure rate, Trussell increased (by 10 times) his typical use failure rate for DMPA from 0.3% to 3%.[40][41]

- DMPA estimated typical use first-year failure rate = 3% in:

Trussell did not use 1995 NSFG failure rates as typical use failure rates for the other two then newly available long-acting contraceptives, the

Advantages

DMPA has a number of advantages and benefits:[48][49][39][50]

- Highly effective at preventing pregnancy.[citation needed]

- Injected every 12 weeks. The only continuing action is to book subsequent follow-up injections every twelve weeks, and to monitor side effects to ensure that they do not require medical attention.[citation needed]

- No estrogen. No increased risk of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, stroke, or myocardial infarction.[citation needed]

- Minimal hormonal contraceptives).[citation needed]

- Decreased risk of endometrial cancer. DMPA reduces the risk of endometrial cancer by 80%.[51][52][53] The reduced risk of endometrial cancer in DMPA users is thought to be due to both the direct anti-proliferative effect of progestogen on the endometrium and the indirect reduction of estrogen levels by suppression of ovarian follicular development.[54]

- Decreased risk of

- Decreased symptoms of endometriosis.

- Decreased incidence of primary dysmenorrhea, ovulation pain, and functional ovarian cysts.

- Decreased incidence of antiepileptic drugs.[57]

- Decreased incidence and severity of sickle cell crises in women with sickle-cell disease.[39]

The United Kingdom Department of Health has actively promoted

Comparison

Proponents of

Available forms

MPA is available alone in the form of 2.5, 5, and 10 mg

Depo-Provera is the brand name for a 150 mg microcrystalline aqueous suspension of DMPA that is administered by intramuscular injection. The shot must be injected into thigh, buttock, or deltoid muscle four times a year (every 11 to 13 weeks), and provides pregnancy protection instantaneously after the first injection.[68] Depo-subQ Provera 104 is a variation of the original intramuscular DMPA that is instead a 104 mg microcrystalline dose in aqueous suspension administered by subcutaneous injection. It contains 69% of the MPA found in the original intramuscular DMPA formulation. It can be injected using a smaller injection needle inserting the medication just below the skin, instead of into the muscle, in either the abdomen or thigh. This subcutaneous injection claims to reduce the side effects of DMPA while still maintaining all the same benefits of the original intramuscular DMPA.

Contraindications

MPA is not usually recommended because of unacceptable health risk or because it is not indicated in the following cases:[69][70]

Conditions where the theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages of using DMPA:

- Multiple risk factors for arterial cardiovascular disease

- Current pulmonary embolus

- Migraine headache with aurawhile using DMPA

- Before evaluation of unexplained vaginal bleeding suspected of being a serious condition

- A history of breast cancer and no evidence of current disease for five years

- Active liver tumours)

- Conditions of concern for HDLlevels theoretically increasing cardiovascular risk:

- Hypertension with vascular disease

- Current and history of ischemic heart disease

- History of stroke

- Diabetes for over 20 years or with nephropathy/retinopathy/neuropathy or vascular disease

Conditions which represent an unacceptable health risk if DMPA is used:

- Current or recent breast cancer (a hormonally sensitive tumour)

Conditions where use is not indicated and should not be initiated:

MPA is not recommended for use prior to menarche or before or during recovery from surgery.[71]

Side effects

In women, the most common

At high doses for the treatment of breast cancer, MPA can cause weight gain and can worsen

When used as a form of injected birth control, there is a delayed return of fertility. The average return to fertility is 9 to 10 months after the last injection, taking longer for overweight or obese women. By 18 months after the last injection, fertility is the same as that in former users of other contraceptive methods.[48][49] Fetuses exposed to progestogens have demonstrated higher rates of genital abnormalities, low birth weight, and increased ectopic pregnancy particularly when MPA is used as an injected form of long-term birth control. A study of accidental pregnancies among poor women in Thailand found that infants who had been exposed to DMPA during pregnancy had a higher risk of low birth weight and an 80% greater-than-usual chance of dying in the first year of life.[77]

Mood changes

There have been concerns about a possible risk of depression and mood changes with progestins like MPA, and this has led to reluctance of some clinicians and women to use them.[78][79] However, contrary to widely-held beliefs, most research suggests that progestins do not cause adverse psychological effects such as depression or anxiety.[78] A 2018 systematic review of the relationship between progestin-based contraception and depression included three large studies of DMPA and reported no association between DMPA and depression.[80] According to a 2003 review of DMPA, the majority of published clinical studies indicate that DMPA is not associated with depression, and the overall data support the notion that the medication does not significantly affect mood.[81]

In the largest study to have assessed the relationship between MPA and depression to date, in which over 3,900 women were treated with DMPA for up to 7 years, the incidence of depression was infrequent at 1.5% and the discontinuation rate due to depression was 0.5%.[80][38][82] This study did not include baseline data on depression,[82] and due to the incidence of depression in the study, the FDA required package labeling for DMPA stating that women with depression should be observed carefully and that DMPA should be discontinued if depression recurs.[80] A subsequent study of 495 women treated with DMPA over the course of 1 year found that the mean depression score slightly decreased in the whole group of continuing users from 7.4 to 6.7 (by 9.5%) and decreased in the quintile of that group with the highest depression scores at baseline from 15.4 to 9.5 (by 38%).[82] Based on the results of this study and others, a consensus began emerging that DMPA does not in fact increase the risk of depression nor worsen the severity of pre-existing depression.[76][82][38]

Similarly to the case of DMPA for hormonal contraception, the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS), a study of 2,763 postmenopausal women treated with 0.625 mg/day oral CEEs plus 2.5 mg/day oral MPA or placebo for 36 months as a method of

Long-term effects

The

When combined with CEEs, MPA has been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer,

Long-term studies of users of DMPA have found slight or no increased overall risk of breast cancer. However, the study population did show a slightly increased risk of breast cancer in recent users (DMPA use in the last four years) under age 35, similar to that seen with the use of combined oral contraceptive pills.[73]

| Clinical outcome | Hypothesized effect on risk |

Estrogen and progestogen (CEs 0.625 mg/day p.o. + MPA 2.5 mg/day p.o.) (n = 16,608, with uterus, 5.2–5.6 years follow up) |

Estrogen alone (CEs 0.625 mg/day p.o.) (n = 10,739, no uterus, 6.8–7.1 years follow up) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | AR

|

HR | 95% CI | AR

| ||

Coronary heart disease

|

Decreased | 1.24 | 1.00–1.54 | +6 / 10,000 PYs | 0.95 | 0.79–1.15 | −3 / 10,000 PYs |

| Stroke | Decreased | 1.31 | 1.02–1.68 | +8 / 10,000 PYs | 1.37 | 1.09–1.73 | +12 / 10,000 PYs |

| Pulmonary embolism | Increased | 2.13 | 1.45–3.11 | +10 / 10,000 PYs | 1.37 | 0.90–2.07 | +4 / 10,000 PYs |

Venous thromboembolism

|

Increased | 2.06 | 1.57–2.70 | +18 / 10,000 PYs | 1.32 | 0.99–1.75 | +8 / 10,000 PYs |

| Breast cancer | Increased | 1.24 | 1.02–1.50 | +8 / 10,000 PYs | 0.80 | 0.62–1.04 | −6 / 10,000 PYs |

| Colorectal cancer | Decreased | 0.56 | 0.38–0.81 | −7 / 10,000 PYs | 1.08 | 0.75–1.55 | +1 / 10,000 PYs |

| Endometrial cancer | – | 0.81 | 0.48–1.36 | −1 / 10,000 PYs | – | – | – |

| Hip fractures | Decreased | 0.67 | 0.47–0.96 | −5 / 10,000 PYs | 0.65 | 0.45–0.94 | −7 / 10,000 PYs |

| Total fractures | Decreased | 0.76 | 0.69–0.83 | −47 / 10,000 PYs | 0.71 | 0.64–0.80 | −53 / 10,000 PYs |

| Total mortality | Decreased | 0.98 | 0.82–1.18 | −1 / 10,000 PYs | 1.04 | 0.91–1.12 | +3 / 10,000 PYs |

| Global index | – | 1.15 | 1.03–1.28 | +19 / 10,000 PYs | 1.01 | 1.09–1.12 | +2 / 10,000 PYs |

| Diabetes | – | 0.79 | 0.67–0.93 | 0.88 | 0.77–1.01 | ||

| Gallbladder disease | Increased | 1.59 | 1.28–1.97 | 1.67 | 1.35–2.06 | ||

| Stress incontinence | – | 1.87 | 1.61–2.18 | 2.15 | 1.77–2.82 | ||

Urge incontinence

|

– | 1.15 | 0.99–1.34 | 1.32 | 1.10–1.58 | ||

| Peripheral artery disease | – | 0.89 | 0.63–1.25 | 1.32 | 0.99–1.77 | ||

| Probable dementia | Decreased | 2.05 | 1.21–3.48 | 1.49 | 0.83–2.66 | ||

| Abbreviations: CEs = coronary heart disease, stroke, pulmonary embolism, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer (estrogen plus progestogen group only), hip fractures, and death from other causes. Sources: See template.

| |||||||

Blood clots

DMPA has been associated in multiple studies with a higher risk of

Bone density

DMPA may cause reduced bone density in premenopausal women and in men when used without an estrogen, particularly at high doses, though this appears to be reversible to a normal level even after years of use.

On 17 November 2004, the United States Food and Drug Administration put a black box warning on the label, indicating that there were potential adverse effects of loss of bone mineral density.[100][101] While it causes temporary bone loss, most women fully regain their bone density after discontinuing use.[75] The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that the use not be restricted.[102][103] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists notes that the potential adverse effects on BMD be balanced against the known negative effects of unintended pregnancy using other birth control methods or no method, particularly among adolescents.

Three studies have suggested that bone loss is reversible after the discontinuation of DMPA.[104][105][106] Other studies have suggested that the effect of DMPA use on postmenopausal bone density is minimal,[107] perhaps because DMPA users experience less bone loss at menopause.[108] Use after peak bone mass is associated with increased bone turnover but no decrease in bone mineral density.[109]

The FDA recommends that DMPA not be used for longer than two years, unless there is no viable alternative method of contraception, due to concerns over bone loss.

HIV risk

There is uncertainty regarding the risk of HIV acquisition among DMPA users; some observational studies suggest an increased risk of HIV acquisition among women using DMPA, while others do not.[111] The World Health Organization issued statements in February 2012 and July 2014 saying the data did not warrant changing their recommendation of no restriction – Medical Eligibility for Contraception (MEC) category 1 – on the use of DMPA in women at high risk for HIV.[112][113] Two meta-analyses of observational studies in sub-Saharan Africa were published in January 2015.[114] They found a 1.4- to 1.5-fold increase risk of HIV acquisition for DMPA users relative to no hormonal contraceptive use.[115][116] In January 2015, the Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists issued a statement reaffirming that there is no reason to advise against use of DMPA in the United Kingdom even for women at 'high risk' of HIV infection.[117] A systematic review and meta-analysis of risk of HIV infection in DMPA users published in fall of 2015 stated that "the epidemiological and biological evidence now make a compelling case that DMPA adds significantly to the risk of male-to-female HIV transmission."[118] In 2019, a randomized controlled trial found no significant association between DMPA use and HIV.[119]

Breastfeeding

MPA may be used by

A larger study with longer follow-up concluded that "use of DMPA during pregnancy or breastfeeding does not adversely affect the long-term growth and development of children". This study also noted that "children with DMPA exposure during pregnancy and lactation had an increased risk of suboptimal growth in height," but that "after adjustment for socioeconomic factors by multiple logistic regression, there was no increased risk of impaired growth among the DMPA-exposed children." The study also noted that effects of DMPA exposure on puberty require further study, as so few children over the age of 10 were observed.[121]

Overdose

MPA has been studied at "massive" dosages of up to 5,000 mg per day orally and 2,000 mg per day via intramuscular injection, without major

Interactions

MPA increases the risk of

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

MPA acts as an

Progestogen |

PR | AR | ER | GR | MR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | 50 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 100 |

| Chlormadinone acetate | 67 | 5 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Cyproterone acetate | 90 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 8 |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | 115 | 5 | 0 | 29 | 160 |

| Megestrol acetate | 65 | 5 | 0 | 30 | 0 |

| Notes: Values are percentages (%). Reference ligands (100%) were promegestone for the PR, metribolone for the AR, estradiol for the ER, dexamethasone for the GR, and aldosterone for the MR. Sources: [4] | |||||

Progestogenic activity

MPA is a potent

The mechanism of action of progestogen-only contraceptives like DMPA depends on the progestogen activity and dose. High-dose progestogen-only contraceptives, such as DMPA, inhibit

| Compound | Ki (nM) |

EC50 (nM)a |

EC50 (nM)b

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | 4.3 | 0.9 | 25 |

| Medroxyprogesterone | 241 | 47 | 32 |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.15 |

| Footnotes: a = Coactivator recruitment. b = Reporter cell line. Sources: [128] | |||

| Progestogen | OID (mg/day) |

TFD (mg/cycle) |

TFD (mg/day) |

ODP (mg/day) |

ECD (mg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | 300 | 4200 | 200–300 | – | 200 |

| Chlormadinone acetate | 1.7 | 20–30 | 10 | 2.0 | 5–10 |

| Cyproterone acetate | 1.0 | 20 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | 10 | 50 | 5–10 | ? | 5.0 |

| Megestrol acetate | ? | 50 | ? | ? | 5.0 |

| Abbreviations: OID = ovulation-inhibiting dosage (without additional estrogen). TFD = endometrial transformation dosage. ODP = oral dosage in commercial contraceptive preparations. ECD = estimated comparable dosage. Sources: [132][99][136] | |||||

| Compound | Form | Dose for specific uses (mg)[c] | DOA[d] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFD[e] | POICD[f] | CICD[g] | ||||

| Algestone acetophenide | Oil soln. | - | – | 75–150 | 14–32 d | |

| Gestonorone caproate | Oil soln. | 25–50 | – | – | 8–13 d | |

| Hydroxyprogest. acetate[h] | Aq. susp. | 350 | – | – | 9–16 d | |

| Hydroxyprogest. caproate | Oil soln. | 250–500[i] | – | 250–500 | 5–21 d | |

| Medroxyprog. acetate | Aq. susp. | 50–100 | 150 | 25 | 14–50+ d | |

| Megestrol acetate | Aq. susp. | - | – | 25 | >14 d | |

| Norethisterone enanthate | Oil soln. | 100–200 | 200 | 50 | 11–52 d | |

| Progesterone | Oil soln. | 200[i] | – | – | 2–6 d | |

| Aq. soln. | ? | – | – | 1–2 d | ||

| Aq. susp. | 50–200 | – | – | 7–14 d | ||

|

Notes and sources:

| ||||||

Antigonadotropic and anticorticotropic effects

MPA suppresses the

Oral MPA has been found to suppress testosterone levels in men by about 30% (from 831 ng/dL to 585 ng/dL) at a dosage of 20 mg/day, by about 45–75% (average 60%; to 150–400 ng/dL) at a dosage of 60 mg/day,[160][161][162] and by about 70–75% (from 832 to 862 ng/dL to 214 to 251 ng/dL) at a dosage of 100 mg/day.[163][164] Dosages of oral MPA of 2.5 to 30 mg/day in combination with estrogens have been used to help suppress testosterone levels in transgender women.[165][166][167][168][169][170] One study of injectable MPA in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia reported that a single 150 mg dose suppressed testosterone levels into the defined male castrate range (<58 ng/dL) within 7 days and that castration levels of testosterone were maintained for 3 months.[171] Very high doses of intramuscular MPA of 150 to 500 mg per week (but up to 900 mg per week) have similarly been reported to suppress testosterone levels to less than 100 ng/dL.[160][172] The typical initial dose of intramuscular MPA for testosterone suppression in men with paraphilias is 400 or 500 mg per week.[160]

Androgenic activity

MPA is a potent full agonist of the AR. Its activation of the AR may play an important and major role in its antigonadotropic effects and in its beneficial effects against

MPA shows weak androgenic effects on

Unlike the related steroids megestrol acetate and cyproterone acetate, MPA is not an antagonist of the AR and does not have direct antiandrogenic activity.[4] As such, although MPA is sometimes described as an antiandrogen, it is not a "true" antiandrogen (i.e., AR antagonist).[161]

Glucocorticoid activity

As an agonist of the GR, MPA has

| Steroid | Class | TR (↑)a | GR (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dexamethasone | Corticosteroid | ++ | 100 |

| Ethinylestradiol | Estrogen | – | 0 |

| Etonogestrel | Progestin | + | 14 |

| Gestodene | Progestin | + | 27 |

| Levonorgestrel | Progestin | – | 1 |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | Progestin | + | 29 |

| Norethisterone | Progestin | – | 0 |

| Norgestimate | Progestin | – | 1 |

| Progesterone | Progestogen | + | 10 |

| Footnotes: a = RBA (%) for the glucocorticoid receptor (GR). Strength: – = No effect. + = Pronounced effect. ++ = Strong effect. Sources: [188]

| |||

Steroidogenesis inhibition

MPA has been found to act as a

MPA has been identified as a competitive inhibitor of human

GABAA receptor allosteric modulation

MPA shares some of the same

Clinical studies using massive dosages of up to 5,000 mg/day oral MPA and 2,000 mg/day intramuscular MPA for 30 days in women with advanced breast cancer have reported "no relevant side effects", which suggests that MPA has no meaningful direct action on the GABAA receptor in humans even at extremely high dosages.[122]

Appetite stimulation

Although MPA and the closely related medication

Other activity

MPA weakly stimulates the

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Surprisingly few studies have been conducted on the pharmacokinetics of MPA at postmenopausal replacement dosages.[202][4] The bioavailability of MPA with oral administration is approximately 100%.[4] A single oral dose of 10 mg MPA has been found to result in peak MPA levels of 1.2 to 5.2 ng/mL within 2 hours of administration using radioimmunoassay.[202][203] Following this, levels of MPA decreased to 0.09 to 0.35 ng/mL 12 hours post-administration.[202][203] In another study, peak levels of MPA were 3.4 to 4.4 ng/mL within 1 to 4 hours of administration of 10 mg oral MPA using radioimmunoassay.[202][204] Subsequently, MPA levels fell to 0.3 to 0.6 ng/mL 24 hours after administration.[202][204] In a third study, MPA levels were 4.2 to 4.4 ng/mL after an oral dose of 5 mg MPA and 6.0 ng/mL after an oral dose of 10 mg MPA, both using radioimmunoassay as well.[202][205]

Treatment of postmenopausal women with 2.5 or 5 mg/day MPA in combination with estradiol valerate for two weeks has been found to rapidly increase circulating MPA levels, with

Oral MPA tablets can be administered sublingually instead of orally.[207][208][209] Rectal administration of MPA has also been studied.[210]

With

Distribution

The

Metabolism

The

Elimination

MPA is

Level–effect relationships

With intramuscular administration, the high levels of MPA in the blood inhibit luteinizing hormone and ovulation for several months, with an accompanying decrease in serum progesterone to below 0.4 ng/mL.[211] Ovulation resumes when once blood levels of MPA fall below 0.1 ng/mL.[211] Serum estradiol remains at approximately 50 pg/mL for approximately four months post-injection (with a range of 10–92 pg/mL after several years of use), rising once MPA levels fall below 0.5 ng/mL.[211]

Time–concentration curves

Chemistry

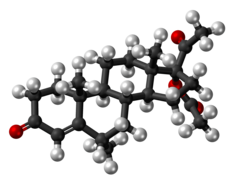

MPA is a

History

MPA was independently discovered in 1956 by

Following its development in the late 1950s, DMPA was first assessed in clinical trials for use as an injectable contraceptive in 1963.[233] Upjohn sought FDA approval of intramuscular DMPA as a long-acting contraceptive under the brand name Depo-Provera (150 mg/mL MPA) in 1967, but the application was rejected.[234][235] However, this formulation was successfully introduced in countries outside of the United States for the first time in 1969, and was available in over 90 countries worldwide by 1992.[36] Upjohn attempted to gain FDA approval of DMPA as a contraceptive again in 1978, and yet again in 1983, but both applications failed similarly to the 1967 application.[234][235] However, in 1992, the medication was finally approved by the FDA, under the brand name Depo-Provera, for use in contraception.[234] A subcutaneous formulation of DMPA was introduced in the United States as a contraceptive under the brand name Depo-SubQ Provera 104 (104 mg/0.65 mL MPA) in December 2004, and subsequently was also approved for the treatment of endometriosis-related pelvic pain.[236]

MPA has also been marketed widely throughout the world under numerous other brand names such as Farlutal, Perlutex, and Gestapuran, among others.[129][11]

Society and culture

Generic names

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is the

Brand names

MPA is marketed under a large number of brand names throughout the world.

Availability

Oral MPA and DMPA are widely available throughout the world.[11] Oral MPA is available both alone and in combination with the estrogens CEEs, estradiol, and estradiol valerate.[11] DMPA is registered for use as a form of birth control in more than 100 countries worldwide.[19][20][11] The combination of injected MPA and estradiol cypionate is approved for use as a form of birth control in 18 countries.[19]

United States

As of November 2016[update], MPA is available in the United States in the following formulations:[64]

- Oral pills: Amen, Curretab, Cycrin, Provera – 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg

- Aqueous suspension for intramuscular injection: Depo-Provera – 150 mg/mL (for contraception), 400 mg/mL (for cancer)

- Aqueous suspension for subcutaneous injection: Depo-SubQ Provera 104 – 104 mg/0.65 mL (for contraception)

It is also available in combination with an estrogen in the following formulations:

- Oral pills: CEEs and MPA (Prempro, Prempro (Premarin, Cycrin), Premphase (Premarin, Cycrin 14/14), Premphase 14/14, Prempro/Premphase) – 0.3 mg / 1.5 mg; 0.45 mg / 1.5 mg; 0.625 mg / 2.5 mg; 0.625 mg / 5 mg

While the following formulations have been discontinued:

- Oral pills: ethinylestradiol and MPA (Provest) – 50 μg / 10 mg

- Aqueous suspension for intramuscular injection: estradiol cypionate and MPA (Lunelle) – 5 mg / 25 mg (for contraception)

The state of Louisiana permits sex offenders to be given MPA.[238]

Generation

Progestins in birth control pills are sometimes grouped by generation.

Controversy

Outside the United States

- In 1994, when DMPA was approved in India, India's Economic and Political Weekly reported that "The FDA finally licensed the drug in 1990 in response to concerns about the population explosion in the third world and the reluctance of third world governments to license a drug not licensed in its originating country."[242] Some scientists and women's groups in India continue to oppose DMPA.[243] In 2016, India introduced DMPA depo-medroxyprogesterone IM preparation in the public health system.[244]

- The Canadian Coalition on Depo-Provera, a coalition of women's health professional and advocacy groups, opposed the approval of DMPA in Canada.class-action lawsuit has been filed against Pfizer by users of DMPA who developed osteoporosis. In response, Pfizer argued that it had met its obligation to disclose and discuss the risks of DMPA with the Canadian medical community.[246]

- Clinical trials for this medication regarding women in Medical Experimentation in Africa.

- A controversy erupted in Israel when the government was accused of giving DMPA to Ethiopian immigrants without their consent. Some women claimed they were told it was a vaccination. The Israeli government denied the accusations but instructed the four health maintenance organizations to stop administering DMPA injections to women "if there is the slightest doubt that they have not understood the implications of the treatment".[247]

United States

There was a long, controversial history regarding the approval of DMPA by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The original manufacturer, Upjohn, applied repeatedly for approval. FDA advisory committees unanimously recommended approval in 1973, 1975 and 1992, as did the FDA's professional medical staff, but the FDA repeatedly denied approval. Ultimately, on 29 October 1992, the FDA approved DMPA for birth control, which had by then been used by over 30 million women since 1969 and was approved and being used by nearly 9 million women in more than 90 countries, including the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Sweden, Thailand, New Zealand and Indonesia.[248] Points in the controversy included:

- Animal testing for rhesus monkeys.[250] However, subsequent studies have shown that in humans, DMPA reduces the risk of endometrial cancer by approximately 80%.[51][52][53]

Speaking in comparative terms regarding animal studies of carcinogenicity for medications, a member of the FDA's Bureau of Drugs testified at an agency DMPA hearing, "...Animal data for this drug is more worrisome than any other drug we know of that is to be given to well people." - Cervical cancer in Upjohn/NCI studies. Cervical cancer was found to be increased as high as 9-fold in the first human studies recorded by the manufacturer and the National Cancer Institute.[251] However, numerous larger subsequent studies have shown that DMPA use does not increase the risk of cervical cancer.[252][253][254][255][256]

- Coercion and lack of informed consent. Testing or use of DMPA was focused almost exclusively on women in developing countries and poor women in the United States,[257] raising serious questions about coercion and lack of informed consent, particularly for the illiterate[258] and for mentally disabled people, who in some reported cases were given DMPA long-term for reasons of "menstrual hygiene", although they were not sexually active.[259]

- Atlanta/Grady Study – Upjohn studied the effect of DMPA for 11 years in Atlanta, mostly on black women who were receiving public assistance, but did not file any of the required follow-up reports with the FDA. Investigators who eventually visited noted that the studies were disorganized. "They found that data collection was questionable, consent forms and protocol were absent; that those women whose consent had been obtained at all were not told of possible side effects. Women whose known medical conditions indicated that use of DMPA would endanger their health were given the shot. Several of the women in the study died; some of cancer, but some for other reasons, such as suicide due to depression. Over half the 13,000 women in the study were lost to followup due to sloppy record keeping." Consequently, no data from this study was usable.[257]

- WHO Review – In 1992, the WHO presented a review of DMPA in four developing countries to the FDA. The National Women's Health Network and other women's organizations testified at the hearing that the WHO was not objective, as the WHO had already distributed DMPA in developing countries. DMPA was approved for use in United States on the basis of the WHO review of previously submitted evidence from countries such as Thailand, evidence which the FDA had deemed insufficient and too poorly designed for assessment of cancer risk at a prior hearing.

- The Alan Guttmacher Institute has speculated that United States approval of DMPA may increase its availability and acceptability in developing countries.[257][260]

- In 1995, several women's health groups asked the FDA to put a moratorium on DMPA, and to institute standardized informed consent forms.[261]

Research

DMPA was studied by

High-dose oral and intramuscular MPA monotherapy has been studied in the treatment of prostate cancer but was found to be inferior to monotherapy with

DMPA has been studied for use as a potential male hormonal contraceptive in combination with the androgens/anabolic steroids testosterone and nandrolone (19-nortestosterone) in men.[270] However, it was never approved for this indication.[270]

MPA was investigated by InKine Pharmaceutical, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and the

MPA has been found to be effective in the treatment of manic symptoms in women with bipolar disorder.[273]

Veterinary use

MPA has been used to reduce

See also

- Conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate

- Estradiol/medroxyprogesterone acetate

- Estradiol cypionate/medroxyprogesterone acetate

- Polyestradiol phosphate/medroxyprogesterone acetate

References

- ^ "Medroxyprogesterone Uses, Dosage & Side Effects".

- FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Product monograph brand safety updates". Health Canada. February 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ S2CID 24616324.

- ^ PMID 19434889.

- ^ a b c d e f "Provera" (PDF). FDA. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ a b c "Depo_Provera" (PDF). FDA. 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d "depo-subQ Provera" (PDF). FDA. 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ S2CID 23985966.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Medroxyprogesterone Acetate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Medroxyprogesterone Uses, Dosage & Side Effects". Drugs.com.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85070-486-7. Archivedfrom the original on 20 May 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-806202-9.

[...] medroxyprogesterone acetate, also known as Provera (discovered simultaneously by Searle and Upjohn in 1956) [..]

- ^ ISBN 0-471-89980-1.

- hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ISBN 978-1-59259-700-0.

- ISBN 978-92-4-156208-9.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ ISSN 2278-4357. Archived from the original(PDF) on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-93-5025-240-6.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Medroxyprogesterone - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- PMID 22895916.

- ^ a b "Medroxyprogesterone". MedlinePlus. 9 January 2008. Archived from the original on 12 July 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ S2CID 244295.

- (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2016.

- ^ "The chemical knife". Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- ^ a b Depo-Provera (medroxyprogesterone acetate) (NDA # 012541) - Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products, retrieved 2 April 2018,

Original Approvals or Tentative Approvals: 09/23/1960.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-444-53271-8. Archivedfrom the original on 23 October 2014.

- S2CID 23378403.

- PMID 2974757.

- PMID 1534051.

- S2CID 42507159.

- ISBN 978-93-5025-777-7.

- ISBN 978-3-642-74614-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4786-0976-6.

- ^ OCLC 781956734. Table 26–1 = Table 3–2 Percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of typical use and the first year of perfect use of contraception, and the percentage continuing use at the end of the first year. United States. Archived 15 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ S2CID 11340062.

- ^ PMID 12954518.

- ^ ISBN 0-9664902-5-8.

- ^ PMID 15288211.

- PMID 2199875.

- ISBN 0-8290-3171-5.

- ISBN 0-9664902-0-7.

- ^ FDA (1998). "Guidance for Industry - Uniform Contraceptive Labeling" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ Trussell J (2007). "Contraceptive Efficacy". In Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates W, Stewart FH, Kowal D (eds.). Contraceptive Technology (19th rev. ed.). New York: Ardent Media. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2008.

- ^ ISBN 0-9664902-5-8.

- ^ ISBN 0-7817-6488-2.

- ISBN 0-7216-9546-9.

- ^ S2CID 39556669.

- ^ PMID 10454658.

- ^ S2CID 221776781.

- ISBN 0-7216-9546-9.

- OCLC 781956734.

Advantages of DMPA Injectables. 5. Reduced risk of ectopic pregnancy. Compared with women who use no contraceptive at all, women who use DMPA have a reduced risk for having an ectopic pregnancy. Although the overall risk of pregnancy and thus ectopic pregnancy is lowered by DMPA, the possibility of an ectopic pregnancy should be excluded if a woman using DMPA becomes pregnant. One study showed that 1.5% of women who got pregnant on DMPA had an ectopic pregnancy, the same ectopic rate as women who conceived while not using contraception.27

- PMID 12384205.

- S2CID 22284176.

- ^ "Increasing use of long-acting reversible contraception". Nursing Times.net. 21 October 2008. Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- ^ "CG30 Long-acting reversible contraception: quick reference guide" (PDF). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- ^ "Sexual Health Ruleset" (PDF). New GMS Contract Quality and Outcome Framework - Implementation Dataset and Business Rules. Primary Care Commissioning. 1 May 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

Summarized at

* "Contraception - Management QOF indicators". NHS Clinical Knowledge Summaries. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Retrieved 19 June 2009.[permanent dead link] - ^ S2CID 2060730. Archived from the original(PDF) on 8 July 2011.

- PMID 17627398. Archived from the original(PDF) on 6 January 2011.

- S2CID 22449765.

- ^ a b c d "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-323-11246-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7295-8162-2.

- ISBN 978-3-662-08110-5.

- ^ Stacey, Dawn. Depo Provera: The Birth Control Shot Archived 10 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 13 October 2009.

- ISBN 92-4-156266-8. Archivedfrom the original on 31 May 2009.

- ^ FFPRHC (2006). "The UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (2005/2006)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2007.

- ^ a b c d "MedroxyPROGESTERone: Drug Information Provided by Lexi-Comp". Merck Manual. 1 December 2009. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ISBN 978-1-4614-5559-2. Archivedfrom the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ a b Pfizer (October 2004). "Depo-Provera Contraceptive Injection, US patient labeling" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2007.

- PMID 720068.

- ^ ISSN 1747-4108.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-444-53716-4.

Perhaps surprisingly, a consensus seems to be emerging that depot medroxyprogesterone acetate implants do not in fact result in an increase in the incidence of depression or in the severity of pre-existing depression, even after 1 or 2 years, nor do they cause significant weight gain.

- PMID 12286194.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-08-055309-2.

- PMID 10338269.

Despite the efficacy and increasing acceptability of these long-term methods, some clinicians and women are reluctant to use them because of concerns regarding reduction in bone density with DMPA, and depressive symptoms and body weight issues with both injectables and implants. Recent multicenter experience showed no increase in depressive symptoms after 1 year's DMPA use and 2 years' Norplant use, even among users with the highest mean depressive symptom scores pre-therapy.

- ^ S2CID 3644828.

- PMID 12954518.

Another common patient tolerability concern reported with hormonal contraception is the effect on mood [95]. The majority of published reports indicate that DMPA does not cause depressive symptoms. In a large, 1-year, clinical trial of DMPA in 3857 US women, fewer than 2% of users reported depression [15]. Other reports in various settings, including a private practice [96], adolescent clinics [97,98], a psychiatric hospital [99] and inner-city family-planning clinics [100,101], have not found an adverse effect of DMPA on depression. [...] Using a variety of objective indices for depressive symptoms, the overall data for both OCs and DMPA are supportive that these agents have no significant effect on mood. Although history of mood symptoms prior to OC use may predispose a subgroup of women to negative mood changes, the data for DMPA suggest that even women who have depressive symptoms prior to treatment can tolerate therapy with no exacerbation of these symptoms.

- ^ PMID 9649914.

- ISBN 978-0-12-378554-1.

- ISBN 978-1-934465-05-9.

- PMID 11829697.

- S2CID 35891204.

- S2CID 20149703.

- PMID 18348708.

- S2CID 31593637.

- ^ S2CID 51628832.

- ^ S2CID 28053690.

- ^ PMID 22872710.

- ^ PMID 30741807.

- S2CID 32394836.

- S2CID 45898359.

- S2CID 58947063.

- ^ S2CID 4229701.

- ^ S2CID 23760705.

- ^ a b Kuhl H (2011). "Pharmacology of Progestogens" (PDF). J Reproduktionsmed Endokrinol. 8 (1): 157–177. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2016.

- ^ "Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and bone effects. Committee Opinion #602". June 2014. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ a b FDA (17 November 2004). "Black Box Warning Added Concerning Long-Term Use of Depo-Provera Contraceptive Injection". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 21 December 2005. Retrieved 12 May 2006.

- ^ World Health Organization (September 2005). "Hormonal contraception and bone health". Family Planning. Archived from the original on 14 May 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2006.

- PMID 16627031.

- PMID 8111260.

- PMID 12192229.

- PMID 15699307.

- S2CID 22565912.

- PMID 12015524.

- PMID 19013564.

- PMID 18757687.

- PMID 25183264.

- ^ WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research (16 February 2012). "Technical Statement: Hormonal contraception and HIV". Geneva: World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 30 January 2015.

- ^ WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research (23 July 2014). "2014 Guidance Statement: Hormonal contraceptive methods for women at high risk of HIV and living with HIV" (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2015.

- ^ AVAC (27 January 2015). "News from the HC-HIV front: it's raining meta (analyses)!". New York: AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition. Archived from the original on 30 January 2015.

- PMID 25578825.

- PMID 25612136.

- ^ Faculty of Sexual Reproductive Healthcare (January 2015). "CEU Statement: Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA, Depo-Provera) and risk of HIV acquisition" (PDF). London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2015.

- PMID 26710371.

- PMID 31204114.

- S2CID 8295162.

- PMID 1387602.

- ^ PMID 1390312.

- PMID 350387.

- PMID 9452274.

- ISBN 978-92-5-105195-5. Archivedfrom the original on 17 June 2014.

- ^ PMID 10077001.

- S2CID 25584803.

- ^ S2CID 24703323.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Archivedfrom the original on 19 June 2013.

- S2CID 45767999.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4832-7738-7.

- ^ PMID 14670641.

- ISBN 978-0-7216-0376-6.

- ISBN 0-07-142280-3.

- ^ PMID 10561657.

- ISBN 978-1-4511-4847-3.

- ISBN 978-3-662-00942-0.

- ISBN 978-3-642-95583-9.

- ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8.

- ISBN 978-94-009-8195-9.

- ISBN 9783110006148.

17α-Hydroxyprogesterone caproate is a depot progestogen which is entirely free of side actions. The dose required to induce secretory changes in primed endometrium is about 250 mg. per menstrual cycle.

- ISBN 978-3-11-150424-7.

- OCLC 278011135.

- ISBN 978-0-8247-8291-7.

- ISBN 978-0-12-137250-7.

- PMID 8013220.

- PMID 8013216.

- ISBN 978-1-4613-2241-2.

- PMID 6452729.

- PMID 6223851.

- ISBN 978-1-4614-0554-2.

- ^ Chu YH, Li Q, Zhao ZF (April 1986). "Pharmacokinetics of megestrol acetate in women receiving IM injection of estradiol-megestrol long-acting injectable contraceptive". The Chinese Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

The results showed that after injection the concentration of plasma MA increased rapidly. The meantime of peak plasma MA level was 3rd day, there was a linear relationship between log of plasma MA concentration and time (day) after administration in all subjects, elimination phase half-life t1/2β = 14.35 ± 9.1 days.

- ISBN 978-3-642-73790-9.

- ISBN 978-1-84214-071-0.

- ISBN 978-1-284-02542-2.

- ^ S2CID 26116247.

- S2CID 12567639.

- ISBN 978-0-19-517704-6. Archivedfrom the original on 17 June 2014.

- ISBN 978-92-4-154765-9.

- ^ ISSN 1072-0162.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-89042-280-9.

- PMID 8891323.

- PMID 6449127.

- PMID 5066846.

- S2CID 144580633.

- S2CID 39706760.

- PMID 17986639.

- ^ Deutsch M (17 June 2016). "Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People" (PDF) (2nd ed.). University of California, San Francisco: Center of Excellence for Transgender Health. p. 28.

- ^ Dahl M, Feldman JL, Goldberg J, Jaberi A (2015). "Endocrine Therapy for Transgender Adults in British Columbia: Suggested Guidelines" (PDF). Vancouver Coastal Health. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- PMID 29756046.

- PMID 8536777.

- PMID 3155506.

- S2CID 12044431.

- PMID 16166329.

- ISBN 978-1-84214-212-7. Archivedfrom the original on 31 December 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-444-53271-8. Archivedfrom the original on 31 December 2013.

- PMID 590535.

- PMID 1200527.

- PMID 4332067.

- ^ ISSN 0144-3615.

- ^ S2CID 3076514.

- PMID 2362454.

- PMID 2141886.

- PMID 2968646.

- PMID 2144198.

- ^ Systemic Effects of Oral Glucocorticoids, archived from the original on 28 January 2014

- S2CID 23343761.

- S2CID 24616324.

- ^ PMID 6213817.

- ^ PMID 2933398.

- PMID 15181090.

- S2CID 5830825.

- ^ S2CID 11605131.

- ^ PMID 10372718.

- ^ S2CID 21796848.

- ^ S2CID 42764270.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-6854-6.

- ISBN 978-1-4200-4895-7.

Medroxyprogesterone [acetate] has similarly been shown to increase appetite and food intake with stabilization of body weight at a dose of 1000 mg (500 mg twice daily).13 Although the drug may be used at 500 to 4000 mg daily, side effects increase above oral doses of 1000 mg daily.16

- ISBN 978-0-19-856698-4. Archivedfrom the original on 18 June 2013.

- ^ S2CID 29808177.

- PMID 31512725.

- ^ S2CID 22731802.

- ^ PMID 975821.

- ^ S2CID 24777672.

- PMID 8015506.

- ^ PMID 15036491.

- ^ "Medroxyprogesterone Acetate - Drug Summary". Prescribers' Digital Reference (PDR). ConnectiveRx. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

When needed, tablets may be administered sublingually†; absorption is adequate by this route.

- PMID 1101759.

The sublingual route was chosen to avoid any irregular absorption that might result from simultaneous food intake.

- PMID 31127826.

- S2CID 11720029.

- ^ PMID 8725700.

- ^ PMID 8013220.

- ^ S2CID 26021562.

- ^ ISSN 0168-3659.

- ISSN 0378-5173.

- PMID 1271819.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4698-9455-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4613-2241-2.

- PMID 833262.

- PMID 6451351.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archivedfrom the original on 5 November 2017.

- PMID 19158035.

- ^ "FMPA - AdisInsight". adisinsight.springer.com.

- ^ FR 1295307, "Procédé de préparation de dérivés cyclopentano-phénanthréniques", published 8 June 1962, assigned to Syntex SA

- ^ US granted 3377364, Spero G, "6-methyl-17alpha-hydroxyprogesterone, the lower fatty acid 17-acylates and methods for producing the same", published 9 April 1968, assigned to Upjohn Company

- ^ Green W (1987). "Odyssey of Depo-Provera: Contraceptives, Carcinogenic Drugs, and Risk-Management Analyses". Food Drug Cosmetic Law Journal (42). Chicago: 567–587.

Depo-Provera is a drug, manufactured by The Upjohn Co., whose active ingredient is medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). FDA first approved the drug in 1959 to treat amenorrhea,5 irregular uterine bleeding, and threatened and habitual abortion.

- PMID 23617013.

- ^ Gelijns A (1991). Innovation in Clinical Practice: The Dynamics of Medical Technology Development. National Academies. pp. 167–. NAP:13513.

- ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3.

- ^ Kolbe HK (1976). Population/fertility control thesaurus (PDF). Population Information Program, Science Communication Division, Dept. of Medical and Public Affairs, George Washington University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2016.

- ^ Bolivar De Lee J (1966). The ... Year Book of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Year Book Publishers. p. 339.

One of these is medroxyprogesterone acetate, which is sold in the United States by Upjohn as Provest, and is obtainable abroad as Provestral, Provestrol, Cyclo-Farlutal, and the more frankly suggestive Nogest.

- ^ Fínkelstein M (1966). Research on Steroids. Pergamon. pp. 469, 542.

- ISBN 978-1-4419-0685-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-316-29840-4.

- ^ a b Documentation on Women's Concerns. Library and Documentation Centre, All India Association for Christian Higher Education. January 1998.

Upjohn meanwhile, had been repeatedly seeking FDA approval for use of DMPA as a contraceptive, but applications were rejected in 1967, 1978 and yet again in 1983, [...]

- ISBN 978-3-319-20185-6.

- ISBN 978-0-7514-0499-9.

- ^ Louisiana State Legislature. "§43.6. Administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) to certain sex offenders". Louisiana Revised Statutes. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85070-067-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-832-1291-1.

- ISBN 978-0-9645467-7-6.

- ^ "Contraceptives. Case for public enquiry". Economic and Political Weekly. 29 (15): 825–6. 1994. Popline database document number 096527.

- ^ Sorojini NB (January–March 2005). "Why women's groups oppose injectable contraceptives". Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. 13 (1). Archived from the original on 6 May 2006.

- ^ "Reference Manual for Injectable Contraceptive (MPA)" (PDF). nhm.gov.in. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Boscoe M (6 December 1991). "Canadian Coalition on Depo-Provera letter to The Honorable Benoit Bouchard, National Minister of Health and Welfare". Canadian Women's Health Network. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2006.

- ^ "Class action suit filed over birth control drug". CTV.ca. 19 December 2005. Archived from the original on 13 August 2006. Retrieved 22 August 2006.

- ^ ""Israeli minister appointing team to probe Ethiopian birth control shot controversy". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 20 June 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- from the original on 8 December 2008.

- ^ "Progestins (IARC Summary & Evaluation, Supplement7, 1987)". Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Goodman A (February–March 1985). "The Case Against Depo-Provera - Problems in the U.S". Multinational Monitor. 6 (2 & 3). Archived from the original on 3 October 2006.

- PMID 12335988.

- PMID 7750280.

- PMID 1387601.

- PMID 8585888.

- S2CID 34683749.

- PMID 8725705.

- ^ a b c Hawkins K, Elliott J (5 May 1996). "Seeking Approval". Albion Monitor. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- PMID 12257656.

- PMID 8341476.

- PMID 7662691.

- PMID 12319319.

- PMID 865726.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-0097-9.

- PMID 5925038.

- ^ Beckman H (1967). The Year Book of Drug Therapy. Year Book Publishers.

- ISBN 978-0-12-800077-9.

- PMID 11842755.

- PMID 9088277.

- ISBN 978-1-85317-422-3.

- ^ PMID 20933120.

- ^ a b c "Medroxyprogesterone - InKine - AdisInsight".

- ^ S2CID 22533823.

- PMID 29230399.

- ^ PMID 12701517.

![MPA levels with 2.5 or 5 mg/day oral MPA in combination with 1 or 2 mg/day estradiol valerate (Indivina) in postmenopausal women[206]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d3/Levels_of_medroxyprogesterone_acetate_with_2.5_or_5_mg_per_day_oral_medroxyprogesterone_acetate_in_postmenopausal_women.png/300px-Levels_of_medroxyprogesterone_acetate_with_2.5_or_5_mg_per_day_oral_medroxyprogesterone_acetate_in_postmenopausal_women.png)

![MPA levels after a single 150 mg intramuscular injection of MPA (Depo-Provera) in aqueous suspension in women[218][219]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/52/Medroxyprogesterone_acetate_levels_after_a_single_150_mg_intramuscular_injection_of_medroxyprogesterone_acetate_in_women.png/300px-Medroxyprogesterone_acetate_levels_after_a_single_150_mg_intramuscular_injection_of_medroxyprogesterone_acetate_in_women.png)

![MPA levels after a single 25 to 150 mg intramuscular injection of MPA (Depo-Provera) in aqueous suspension in women[218][220]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/Medroxyprogesterone_acetate_levels_after_a_single_intramuscular_injection_of_different_doses_of_medroxyprogesterone_acetate_in_women.png/300px-Medroxyprogesterone_acetate_levels_after_a_single_intramuscular_injection_of_different_doses_of_medroxyprogesterone_acetate_in_women.png)

![MPA levels after a single 104 mg subcutaneous injection of MPA (Depo-SubQ Provera) in aqueous suspension in women[8]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f0/Medroxyprogesterone_acetate_levels_with_a_subcutaneous_injection_of_104_mg_medroxyprogesterone_acetate_in_women.png/300px-Medroxyprogesterone_acetate_levels_with_a_subcutaneous_injection_of_104_mg_medroxyprogesterone_acetate_in_women.png)