Mental disorder

| Mental disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Mental breakdown, mental disability, mental disease, mental health condition, mental illness, nervous breakdown, psychiatric disability, psychiatric disorder, psychological disability, psychological disorder psychotic disorders, substance use disorders |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors |

| Treatment | Psychotherapy and medications |

| Medication | Antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, mood stabilizers, stimulants |

| Frequency | 18% per year (United States)[5] |

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness,

The

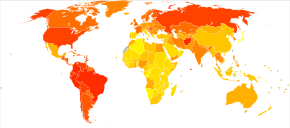

In 2019, common mental disorders around the globe include:

Definition

The definition and classification of mental disorders are key issues for researchers as well as service providers and those who may be diagnosed. For a mental state to be classified as a disorder, it generally needs to cause dysfunction.[15] Most international clinical documents use the term mental "disorder", while "illness" is also common. It has been noted that using the term "mental" (i.e., of the mind) is not necessarily meant to imply separateness from the brain or body.

According to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (

DSM-IV predicates the definition with caveats, stating that, as in the case with many medical terms, mental disorder "lacks a consistent operational definition that covers all situations", noting that different levels of abstraction can be used for medical definitions, including pathology, symptomology, deviance from a normal range, or etiology, and that the same is true for mental disorders, so that sometimes one type of definition is appropriate and sometimes another, depending on the situation.[17]

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) redefined mental disorders in the DSM-5 as "a syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual's cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning."[18] The final draft of ICD-11 contains a very similar definition.[19]

The terms "mental breakdown" or "nervous breakdown" may be used by the general population to mean a mental disorder.[20] The terms "nervous breakdown" and "mental breakdown" have not been formally defined through a medical diagnostic system such as the DSM-5 or ICD-10 and are nearly absent from scientific literature regarding mental illness.[21][22] Although "nervous breakdown" is not rigorously defined, surveys of laypersons suggest that the term refers to a specific acute time-limited reactive disorder involving symptoms such as anxiety or depression, usually precipitated by external stressors.[21] Many health experts today refer to a nervous breakdown as a mental health crisis.[23]

Nervous illness

In addition to the concept of mental disorder, some people have argued for a return to the old-fashioned concept of nervous illness. In How Everyone Became Depressed: The Rise and Fall of the Nervous Breakdown (2013), Edward Shorter, a professor of psychiatry and the history of medicine, says:

About half of them are depressed. Or at least that is the diagnosis that they got when they were put on antidepressants. ... They go to work but they are unhappy and uncomfortable; they are somewhat anxious; they are tired; they have various physical pains—and they tend to obsess about the whole business. There is a term for what they have, and it is a good old-fashioned term that has gone out of use. They have nerves or a nervous illness. It is an illness not just of mind or brain, but a disorder of the entire body. ... We have a package here of five symptoms—mild depression, some anxiety, fatigue, somatic pains, and obsessive thinking. ... We have had nervous illness for centuries. When you are too nervous to function ... it is a nervous breakdown. But that term has vanished from medicine, although not from the way we speak.... The nervous patients of yesteryear are the depressives of today. That is the bad news.... There is a deeper illness that drives depression and the symptoms of mood. We can call this deeper illness something else, or invent a neologism, but we need to get the discussion off depression and onto this deeper disorder in the brain and body. That is the point.

— Edward Shorter, Faculty of Medicine, the University of Toronto[24]

In eliminating the nervous breakdown, psychiatry has come close to having its own nervous breakdown.

— David Healy, MD, FRCPsych, Professor of Psychiatry, University of Cardiff, Wales[25]

Nerves stand at the core of common mental illness, no matter how much we try to forget them.

— Peter J. Tyrer, FMedSci, Professor of Community Psychiatry, Imperial College, London[26]

"Nervous breakdown" is a pseudo-medical term to describe a wealth of stress-related feelings and they are often made worse by the belief that there is a real phenomenon called "nervous breakdown".

— Richard E. Vatz, co-author of explication of views of Thomas Szasz in "Thomas Szasz: Primary Values and Major Contentions"[page needed]

Classifications

There are currently two widely established systems that classify mental disorders:

- ICD-11 Chapter 06: Mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders, part of the International Classification of Diseases produced by the WHO (in effect since 1 January 2022).[27]

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) produced by the APA since 1952.

Both of these list categories of disorder and provide standardized criteria for diagnosis. They have deliberately converged their codes in recent revisions so that the manuals are often broadly comparable, although significant differences remain. Other classification schemes may be used in non-western cultures, for example, the

Unlike the DSM and ICD, some approaches are not based on identifying distinct categories of disorder using

In the scientific and academic literature on the definition or classification of mental disorder, one extreme argues that it is entirely a matter of value judgements (including of what is

The DSM and ICD approach remains under attack both because of the implied causality model[32] and because some researchers believe it better to aim at underlying brain differences which can precede symptoms by many years.[33]

Dimensional models

The high degree of comorbidity between disorders in categorical models such as the DSM and ICD have led some to propose dimensional models. Studying comorbidity between disorders have demonstrated two latent (unobserved) factors or dimensions in the structure of mental disorders that are thought to possibly reflect etiological processes. These two dimensions reflect a distinction between internalizing disorders, such as mood or anxiety symptoms, and externalizing disorders such as behavioral or substance use symptoms.[34] A single general factor of psychopathology, similar to the g factor for intelligence, has been empirically supported. The p factor model supports the internalizing-externalizing distinction, but also supports the formation of a third dimension of thought disorders such as schizophrenia.[35] Biological evidence also supports the validity of the internalizing-externalizing structure of mental disorders, with twin and adoption studies supporting heritable factors for externalizing and internalizing disorders.[36][37][38] A leading dimensional model is the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology.

Disorders

There are many different categories of mental disorder, and many different facets of human behavior and personality that can become disordered.[39][40][41][42]

Anxiety disorder

An anxiety disorder is

Mood disorder

Other affective (emotion/mood) processes can also become disordered. Mood disorder involving unusually intense and sustained sadness, melancholia, or despair is known as

Psychotic disorder

Patterns of belief, language use and perception of reality can become dysregulated (e.g.,

Personality disorder

Eating disorder

An eating disorder is a serious mental health condition that involves an unhealthy relationship with food and body image. They can cause severe physical and psychological problems.[47] Eating disorders involve disproportionate concern in matters of food and weight.[40] Categories of disorder in this area include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, exercise bulimia or binge eating disorder.[48][49]

Sleep disorder

Sleep disorders are associated with disruption to normal

Narcolepsy is a condition of extreme tendencies to fall asleep whenever and wherever. People with narcolepsy feel refreshed after their random sleep, but eventually get sleepy again. Narcolepsy diagnosis requires an overnight stay at a sleep center for analysis, during which doctors ask for a detailed sleep history and sleep records. Doctors also use actigraphs and polysomnography.[50] Doctors will do a multiple sleep latency test, which measures how long it takes a person to fall asleep.[50]

Sleep apnea, when breathing repeatedly stops and starts during sleep, can be a serious sleep disorder. Three types of sleep apnea include obstructive sleep apnea, central sleep apnea, and complex sleep apnea.[51] Sleep apnea can be diagnosed at home or with polysomnography at a sleep center. An ear, nose, and throat doctor may further help with the sleeping habits.

Sexual disorders include dyspareunia and various kinds of paraphilia (sexual arousal to objects, situations, or individuals that are considered abnormal or harmful to the person or others).

Other

Cognitive disorder: These affect cognitive abilities, including learning and memory. This category includes delirium and mild and major neurocognitive disorder (previously termed dementia).

Somatoform disorders may be diagnosed when there are problems that appear to originate in the body that are thought to be manifestations of a mental disorder. This includes somatization disorder and conversion disorder. There are also disorders of how a person perceives their body, such as body dysmorphic disorder. Neurasthenia is an old diagnosis involving somatic complaints as well as fatigue and low spirits/depression, which is officially recognized by the ICD-10 but no longer by the DSM-IV.[52][non-primary source needed]

Factitious disorders are diagnosed where symptoms are thought to be reported for personal gain. Symptoms are often deliberately produced or feigned, and may relate to either symptoms in the individual or in someone close to them, particularly people they care for.

There are attempts to introduce a category of

There are a number of uncommon psychiatric

Signs and symptoms

Course

The onset of psychiatric disorders usually occurs from childhood to early adulthood.[54] Impulse-control disorders and a few anxiety disorders tend to appear in childhood. Some other anxiety disorders, substance disorders, and mood disorders emerge later in the mid-teens.[55] Symptoms of schizophrenia typically manifest from late adolescence to early twenties.[56]

The likely course and outcome of mental disorders vary and are dependent on numerous factors related to the disorder itself, the individual as a whole, and the social environment. Some disorders may last a brief period of time, while others may be long-term in nature.

All disorders can have a varied course. Long-term international studies of schizophrenia have found that over a half of individuals recover in terms of symptoms, and around a fifth to a third in terms of symptoms and functioning, with many requiring no medication. While some have serious difficulties and support needs for many years, "late" recovery is still plausible. The World Health Organization (WHO) concluded that the long-term studies' findings converged with others in "relieving patients, carers and clinicians of the chronicity paradigm which dominated thinking throughout much of the 20th century."[57][non-primary source needed][58]

A follow-up study by Tohen and coworkers revealed that around half of people initially diagnosed with bipolar disorder achieve symptomatic recovery (no longer meeting criteria for the diagnosis) within six weeks, and nearly all achieve it within two years, with nearly half regaining their prior occupational and residential status in that period. Less than half go on to experience a new episode of mania or major depression within the next two years.[59][non-primary source needed]

Disability

| Disorder | Disability-adjusted life years[60] |

|---|---|

| Major depressive disorder | 65.5 million |

| Alcohol-use disorder | 23.7 million |

| Schizophrenia | 16.8 million |

| Bipolar disorder | 14.4 million |

| Other drug-use disorders | 8.4 million |

| Panic disorder | 7.0 million |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 5.1 million |

| Primary insomnia | 3.6 million |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 3.5 million |

Some disorders may be very limited in their functional effects, while others may involve substantial disability and support needs. In this context, the terms psychiatric disability and psychological disability are sometimes used instead of mental disorder.

It is also the case that, while often being characterized in purely negative terms, some mental traits or states labeled as psychiatric disabilities can also involve above-average creativity, non-conformity, goal-striving, meticulousness, or empathy.[62] In addition, the public perception of the level of disability associated with mental disorders can change.[63]

Nevertheless, internationally, people report equal or greater disability from commonly occurring mental conditions than from commonly occurring physical conditions, particularly in their social roles and personal relationships. The proportion with access to professional help for mental disorders is far lower, however, even among those assessed as having a severe psychiatric disability.[64] Disability in this context may or may not involve such things as:

- Basic activities of daily living. Including looking after the self (health care, grooming, dressing, shopping, cooking etc.) or looking after accommodation (chores, DIY tasks, etc.)

- communication skills, ability to form relationships and sustain them, ability to leave the home or mix in crowds or particular settings

- Occupational functioning. Ability to acquire an employment and hold it, cognitive and social skills required for the job, dealing with workplace culture, or studying as a student.

In terms of total

Suicide, which is often attributed to some underlying mental disorder, is a leading cause of death among teenagers and adults under 35.[66][67] There are an estimated 10 to 20 million non-fatal attempted suicides every year worldwide.[68]

Risk factors

The predominant view as of 2018[update] is that genetic, psychological, and environmental factors all contribute to the development or progression of mental disorders.[69] Different risk factors may be present at different ages, with risk occurring as early as during prenatal period.[70]

Genetics

A number of psychiatric disorders are linked to a family history (including depression, narcissistic personality disorder[71][72] and anxiety).[73] Twin studies have also revealed a very high heritability for many mental disorders (especially autism and schizophrenia).[74] Although researchers have been looking for decades for clear linkages between genetics and mental disorders, that work has not yielded specific genetic biomarkers yet that might lead to better diagnosis and better treatments.[75]

Statistical research looking at eleven disorders found widespread assortative mating between people with mental illness. That means that individuals with one of these disorders were two to three times more likely than the general population to have a partner with a mental disorder. Sometimes people seemed to have preferred partners with the same mental illness. Thus, people with schizophrenia or ADHD are seven times more likely to have affected partners with the same disorder. This is even more pronounced for people with Autism spectrum disorders who are 10 times more likely to have a spouse with the same disorder.[76]

Environment

During the prenatal stage, factors like unwanted pregnancy, lack of adaptation to pregnancy or substance use during pregnancy increases the risk of developing a mental disorder.[70] Maternal stress and birth complications including prematurity and infections have also been implicated in increasing susceptibility for mental illness.[77] Infants neglected or not provided optimal nutrition have a higher risk of developing cognitive impairment.[70]

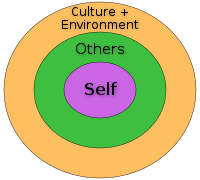

Social influences have also been found to be important,

Nutrition also plays a role in mental disorders.[10][80]

In schizophrenia and psychosis, risk factors include migration and discrimination, childhood trauma, bereavement or separation in families, recreational use of drugs,[81] and urbanicity.[79]

In anxiety, risk factors may include parenting factors including parental rejection, lack of parental warmth, high hostility, harsh discipline, high maternal negative affect, anxious childrearing, modelling of dysfunctional and drug-abusing behavior, and child abuse (emotional, physical and sexual).[82] Adults with imbalance work to life are at higher risk for developing anxiety.[70]

For bipolar disorder, stress (such as childhood adversity) is not a specific cause, but does place genetically and biologically vulnerable individuals at risk for a more severe course of illness.[83]

Drug use

Mental disorders are associated with drug use including:

Chronic disease

People living with chronic conditions like HIV and diabetes are at higher risk of developing a mental disorder. People living with diabetes experience significant stress from the biological impact of the disease, which places them at risk for developing anxiety and depression. Diabetic patients also have to deal with emotional stress trying to manage the disease. Conditions like heart disease, stroke, respiratory conditions, cancer, and arthritis increase the risk of developing a mental disorder when compared to the general population.[90]

Personality traits

Risk factors for mental illness include a propensity for high neuroticism[91][92] or "emotional instability". In anxiety, risk factors may include temperament and attitudes (e.g. pessimism).[73]

Causal models

Mental disorders can arise from multiple sources, and in many cases there is no single accepted or consistent cause currently established. An eclectic or pluralistic mix of models may be used to explain particular disorders.[92][93] The primary paradigm of contemporary mainstream Western psychiatry is said to be the biopsychosocial model which incorporates biological, psychological and social factors, although this may not always be applied in practice.

Diagnosis

Psychiatrists seek to provide a

Routine diagnostic practice in mental health services typically involves an interview known as a

Time and budgetary constraints often limit practicing psychiatrists from conducting more thorough diagnostic evaluations.

More structured approaches are being increasingly used to measure levels of mental illness.

- HoNOS is the most widely used measure in English mental health services, being used by at least 61 trusts.[99] In HoNOS a score of 0–4 is given for each of 12 factors, based on functional living capacity.[100] Research has been supportive of HoNOS,[101] although some questions have been asked about whether it provides adequate coverage of the range and complexity of mental illness problems, and whether the fact that often only 3 of the 12 scales vary over time gives enough subtlety to accurately measure outcomes of treatment.[102]

Criticism

Since the 1980s, Paula Caplan has been concerned about the subjectivity of psychiatric diagnosis, and people being arbitrarily "slapped with a psychiatric label." Caplan says because psychiatric diagnosis is unregulated, doctors are not required to spend much time interviewing patients or to seek a second opinion. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders can lead a psychiatrist to focus on narrow checklists of symptoms, with little consideration of what is actually causing the person's problems. So, according to Caplan, getting a psychiatric diagnosis and label often stands in the way of recovery.[103][unreliable medical source]

In 2013, psychiatrist

Gary Greenberg, a psychoanalyst, in his book "the Book of Woe", argues that mental illness is really about suffering and how the DSM creates diagnostic labels to categorize people's suffering.[107] Indeed, the psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, in his book "the Medicalization of Everyday Life", also argues that what is psychiatric illness, is not always biological in nature (i.e. social problems, poverty, etc.), and may even be a part of the human condition.[108]

Potential routine use of MRI/fMRI in diagnosis

in 2018 the

- "have a sensitivity of at least 80% for detecting a particular psychiatric disorder"

- should "have a specificity of at least 80% for distinguishing this disorder from other psychiatric or medical disorders"

- "should be reliable, reproducible, and ideally be noninvasive, simple to perform, and inexpensive"

- proposed biomarkers should be verified by 2 independent studies each by a different investigator and different population samples and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

The review concluded that although neuroimaging diagnosis may technically be feasible, very large studies are needed to evaluate specific biomarkers which were not available.[109]

Prevention

The 2004 WHO report "Prevention of Mental Disorders" stated that "Prevention of these disorders is obviously one of the most effective ways to reduce the [disease] burden."[110] The 2011 European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on prevention of mental disorders states "There is considerable evidence that various psychiatric conditions can be prevented through the implementation of effective evidence-based interventions."[111] A 2011

Parenting may affect the child's mental health, and evidence suggests that helping parents to be more effective with their children can address mental health needs.[114][115][116]

Universal prevention (aimed at a population that has no increased risk for developing a mental disorder, such as school programs or mass media campaigns) need very high numbers of people to show effect (sometimes known as the "power" problem). Approaches to overcome this are (1) focus on high-incidence groups (e.g. by targeting groups with high risk factors), (2) use multiple interventions to achieve greater, and thus more statistically valid, effects, (3) use cumulative meta-analyses of many trials, and (4) run very large trials.[117][118]

Management

Treatment and support for mental disorders are provided in

There is a range of different types of treatment and what is most suitable depends on the disorder and the individual. Many things have been found to help at least some people, and a placebo effect may play a role in any intervention or medication. In a minority of cases, individuals may be treated against their will, which can cause particular difficulties depending on how it is carried out and perceived. Compulsory treatment while in the community versus non-compulsory treatment does not appear to make much of a difference except by maybe decreasing victimization.[119]

Lifestyle

Lifestyle strategies, including dietary changes, exercise and quitting smoking may be of benefit.[13][80][120]

Therapy

There is also a wide range of

A major option for many mental disorders is psychotherapy. There are several main types. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is widely used and is based on modifying the patterns of thought and behavior associated with a particular disorder. Other psychotherapies include dialectic behavioral therapy (DBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT). Psychoanalysis, addressing underlying psychic conflicts and defenses, has been a dominant school of psychotherapy and is still in use. Systemic therapy or family therapy is sometimes used, addressing a network of significant others as well as an individual.

Some psychotherapies are based on a

Medication

A major option for many mental disorders is

Despite the different conventional names of the drug groups, there may be considerable overlap in the disorders for which they are actually indicated, and there may also be

Other

Epidemiology

Mental disorders are common. Worldwide, more than one in three people in most countries report sufficient criteria for at least one at some point in their life.[130] In the United States, 46% qualify for a mental illness at some point.[131] An ongoing survey indicates that anxiety disorders are the most common in all but one country, followed by mood disorders in all but two countries, while substance disorders and impulse-control disorders were consistently less prevalent.[132] Rates varied by region.[133]

A review of anxiety disorder surveys in different countries found average lifetime prevalence estimates of 16.6%, with women having higher rates on average.[134] A review of mood disorder surveys in different countries found lifetime rates of 6.7% for major depressive disorder (higher in some studies, and in women) and 0.8% for Bipolar I disorder.[135]

In the United States the frequency of disorder is: anxiety disorder (28.8%), mood disorder (20.8%), impulse-control disorder (24.8%) or substance use disorder (14.6%).[131][136][137]

A 2004 cross-Europe study found that approximately one in four people reported meeting criteria at some point in their life for at least one of the DSM-IV disorders assessed, which included mood disorders (13.9%), anxiety disorders (13.6%), or alcohol disorder (5.2%). Approximately one in ten met the criteria within a 12-month period. Women and younger people of either gender showed more cases of the disorder.[138] A 2005 review of surveys in 16 European countries found that 27% of adult Europeans are affected by at least one mental disorder in a 12-month period.[139]

An international review of studies on the prevalence of schizophrenia found an average (median) figure of 0.4% for lifetime prevalence; it was consistently lower in poorer countries.[140]

Studies of the prevalence of personality disorders (PDs) have been fewer and smaller-scale, but one broad Norwegian survey found a five-year prevalence of almost 1 in 7 (13.4%). Rates for specific disorders ranged from 0.8% to 2.8%, differing across countries, and by gender, educational level and other factors.[141] A US survey that incidentally screened for personality disorder found a rate of 14.79%.[142]

Approximately 7% of a preschool pediatric sample were given a psychiatric diagnosis in one clinical study, and approximately 10% of 1- and 2-year-olds receiving developmental screening have been assessed as having significant emotional/behavioral problems based on parent and pediatrician reports.[143]

While rates of psychological disorders are often the same for men and women, women tend to have a higher rate of depression. Each year 73 million women are affected by major depression, and suicide is ranked 7th as the cause of death for women between the ages of 20–59. Depressive disorders account for close to 41.9% of the psychiatric disabilities among women compared to 29.3% among men.[144]

History

Ancient civilizations

Ancient civilizations described and treated a number of mental disorders. Mental illnesses were well known in ancient

Europe

Middle Ages

Conceptions of madness in the Middle Ages in Christian Europe were a mixture of the divine, diabolical, magical and humoral, and transcendental.[147] In the early modern period, some people with mental disorders may have been victims of the witch-hunts. While not every witch and sorcerer accused were mentally ill, all mentally ill were considered to be witches or sorcerers.[148] Many terms for mental disorders that found their way into everyday use first became popular in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Eighteenth century

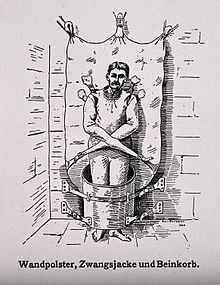

By the end of the 17th century and into the Enlightenment, madness was increasingly seen as an organic physical phenomenon with no connection to the soul or moral responsibility. Asylum care was often harsh and treated people like wild animals, but towards the end of the 18th century a moral treatment movement gradually developed. Clear descriptions of some syndromes may be rare before the 19th century.

Nineteenth century

Industrialization and population growth led to a massive expansion of the number and size of insane asylums in every Western country in the 19th century. Numerous different classification schemes and diagnostic terms were developed by different authorities, and the term psychiatry was coined (1808), though medical superintendents were still known as alienists.

Twentieth century

The turn of the 20th century saw the development of psychoanalysis, which would later come to the fore, along with Kraepelin's classification scheme. Asylum "inmates" were increasingly referred to as "patients", and asylums were renamed as hospitals.

Europe and the United States

Early in the 20th century in the United States, a

Electroconvulsive therapy, insulin shock therapy,

Advances in

Africa and Nigeria

Most Africans view mental disturbances as external

The WHO estimated that fewer than 10% of mentally ill Nigerians have access to a psychiatrist or health worker, because there is a low ratio of mental-health specialists available in a country of 200 million people. WHO estimates that the number of mentally ill Nigerians ranges from 40 million to 60 million. Disorders such as depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, personality disorder, old age-related disorder, and substance-abuse disorder are common in Nigeria, as in other countries in Africa.[152]

Nigeria is still nowhere near being equipped to solve prevailing mental health challenges. With little scientific research carried out, coupled with insufficient mental-health hospitals in the country, traditional healers provide specialized psychotherapy care to those that require their services and pharmacotherapy[153][154]

Society and culture

Different societies or cultures, even different individuals in a subculture, can disagree as to what constitutes optimal versus pathological biological and psychological functioning. Research has demonstrated that cultures vary in the relative importance placed on, for example, happiness, autonomy, or social relationships for pleasure. Likewise, the fact that a behavior pattern is valued, accepted, encouraged, or even statistically normative in a culture does not necessarily mean that it is conducive to optimal psychological functioning.

People in all cultures find some behaviors bizarre or even incomprehensible. But just what they feel is bizarre or incomprehensible is ambiguous and subjective.[155] These differences in determination can become highly contentious. The process by which conditions and difficulties come to be defined and treated as medical conditions and problems, and thus come under the authority of doctors and other health professionals, is known as medicalization or pathologization.

Mental illness in the Latin American community

There is a perception in

Latin Americans from the US are slightly more likely to have a mental health disorder than first-generation Latin American immigrants, although differences between ethnic groups were found to disappear after adjustment for place of birth.[157]

From 2015 to 2018, rates of serious mental illness in young adult Latin Americans increased by 60%, from 4% to 6.4%. The prevalence of major depressive episodes in young and adult Latin Americans increased from 8.4% to 11.3%. More than a third of Latin Americans reported more than one bad mental health day in the last three months.[158] The rate of suicide among Latin Americans was about half the rate of non-Latin American white Americans in 2018, and this was the second-leading cause of death among Latin Americans ages 15 to 34.[159] However, Latin American suicide rates rose steadily after 2020 in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, even as the national rate declined.[160][161]

Family relations are an integral part of the Latin American community. Some research has shown that Latin Americans are more likely rely on family bonds, or familismo, as a source of therapy while struggling with mental health issues. Because Latin Americans have a high rate of religiosity, and because there is less stigma associated with religion than with psychiatric services,[162] religion may play a more important therapeutic role for the mentally ill in Latin American communities. However, research has also suggested that religion may also play a role in stigmatizing mental illness in Latin American communities, which can discourage community members from seeking professional help.[163]

Religion

Religious, spiritual, or transpersonal experiences and beliefs meet many criteria of delusional or psychotic disorders.[164][165] A belief or experience can sometimes be shown to produce distress or disability—the ordinary standard for judging mental disorders.[166] There is a link between religion and schizophrenia,[167] a complex mental disorder characterized by a difficulty in recognizing reality, regulating emotional responses, and thinking in a clear and logical manner. Those with schizophrenia commonly report some type of religious delusion,[167][168][169] and religion itself may be a trigger for schizophrenia.[170]

Movements

Controversy has often surrounded psychiatry, and the term

The

Alternatively, a movement for global mental health has emerged, defined as 'the area of study, research and practice that places a priority on improving mental health and achieving equity in mental health for all people worldwide'.[178]

Cultural bias

Diagnostic guidelines of the 2000s, namely the DSM and to some extent the ICD, have been criticized as having a fundamentally Euro-American outlook. Opponents argue that even when diagnostic criteria are used across different cultures, it does not mean that the underlying constructs have validity within those cultures, as even reliable application can prove only consistency, not legitimacy.

Cross-cultural psychiatrist Arthur Kleinman contends that the Western bias is ironically illustrated in the introduction of cultural factors to the DSM-IV. Disorders or concepts from non-Western or non-mainstream cultures are described as "culture-bound", whereas standard psychiatric diagnoses are given no cultural qualification whatsoever, revealing to Kleinman an underlying assumption that Western cultural phenomena are universal.[181] Kleinman's negative view towards the culture-bound syndrome is largely shared by other cross-cultural critics. Common responses included both disappointment over the large number of documented non-Western mental disorders still left out and frustration that even those included are often misinterpreted or misrepresented.[182]

Many mainstream psychiatrists are dissatisfied with the new culture-bound diagnoses, although for partly different reasons. Robert Spitzer, a lead architect of the

Clinical conceptions of mental illness also overlap with

Such approaches, along with cross-cultural and "

Laws and policies

Three-quarters of countries around the world have mental health legislation. Compulsory admission to mental health facilities (also known as involuntary commitment) is a controversial topic. It can impinge on personal liberty and the right to choose, and carry the risk of abuse for political, social, and other reasons; yet it can potentially prevent harm to self and others, and assist some people in attaining their right to healthcare when they may be unable to decide in their own interests.[191] Because of this it is a concern of medical ethics.

All human rights oriented mental health laws require proof of the presence of a mental disorder as defined by internationally accepted standards, but the type and severity of disorder that counts can vary in different jurisdictions. The two most often used grounds for involuntary admission are said to be serious likelihood of immediate or imminent danger to self or others, and the need for treatment. Applications for someone to be involuntarily admitted usually come from a mental health practitioner, a family member, a close relative, or a guardian. Human-rights-oriented laws usually stipulate that independent medical practitioners or other accredited mental health practitioners must examine the patient separately and that there should be regular, time-bound review by an independent review body.[191] The individual should also have personal access to independent advocacy.

For involuntary treatment to be administered (by force if necessary), it should be shown that an individual lacks the mental capacity for informed consent (i.e. to understand treatment information and its implications, and therefore be able to make an informed choice to either accept or refuse). Legal challenges in some areas have resulted in supreme court decisions that a person does not have to agree with a psychiatrist's characterization of the issues as constituting an "illness", nor agree with a psychiatrist's conviction in medication, but only recognize the issues and the information about treatment options.[192]

Proxy consent (also known as

The World Health Organization reports that in many instances national mental health legislation takes away the rights of persons with mental disorders rather than protecting rights, and is often outdated.[191] In 1991, the United Nations adopted the Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care, which established minimum human rights standards of practice in the mental health field. In 2006, the UN formally agreed the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities to protect and enhance the rights and opportunities of disabled people, including those with psychiatric disabilities.[194]

The term

Perception and discrimination

Stigma

The social stigma associated with mental disorders is a widespread problem. The US Surgeon General stated in 1999 that: "Powerful and pervasive, stigma prevents people from acknowledging their own mental health problems, much less disclosing them to others."[195] Additionally, researcher Wulf Rössler in 2016, in his article, "The Stigma of Mental Disorders" stated

"For millennia, society did not treat persons suffering from depression, autism, schizophrenia and other mental illnesses much better than slaves or criminals: they were imprisoned, tortured or killed".[196]

In the United States, racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to experience mental health disorders often due to low socioeconomic status, and discrimination.[197][198][199] In Taiwan, those with mental disorders are subject to general public's misperception that the root causes of the mental disorders are "over-thinking", "having a lot of time and nothing better to do", "stagnant", "not serious in life", "not paying enough attention to the real life affairs", "mentally weak", "refusing to be resilient", "turning back to perfectionistic strivings", "not bravery" and so forth.[200]

Efforts are being undertaken worldwide to eliminate the stigma of mental illness,[204] although the methods and outcomes used have sometimes been criticized.[205]

Media and general public

Media coverage of mental illness comprises predominantly negative and pejorative depictions, for example, of incompetence, violence or criminality, with far less coverage of positive issues such as accomplishments or human rights issues.[206][207][208] Such negative depictions, including in children's cartoons, are thought to contribute to stigma and negative attitudes in the public and in those with mental health problems themselves, although more sensitive or serious cinematic portrayals have increased in prevalence.[209][210]

In the United States, the Carter Center has created fellowships for journalists in South Africa, the U.S., and Romania, to enable reporters to research and write stories on mental health topics.[211] Former US First Lady Rosalynn Carter began the fellowships not only to train reporters in how to sensitively and accurately discuss mental health and mental illness, but also to increase the number of stories on these topics in the news media.[212][213] There is also a World Mental Health Day, which in the United States and Canada falls within a Mental Illness Awareness Week.

The general public have been found to hold a strong stereotype of dangerousness and desire for social distance from individuals described as mentally ill.[214] A US national survey found that a higher percentage of people rate individuals described as displaying the characteristics of a mental disorder as "likely to do something violent to others", compared to the percentage of people who are rating individuals described as being troubled.[215] In the article, "Discrimination Against People with a Mental Health Diagnosis: Qualitative Analysis of Reported Experiences," an individual who has a mental disorder, revealed that, "If people don't know me and don't know about the problems, they'll talk to me quite happily. Once they've seen the problems or someone's told them about me, they tend to be a bit more wary."[216] In addition, in the article,"Stigma and its Impact on Help-Seeking for Mental Disorders: What Do We Know?" by George Schomerus and Matthias Angermeyer, it is affirmed that "Family doctors and psychiatrists have more pessimistic views about the outcomes for mental illnesses than the general public (Jorm et al., 1999), and mental health professionals hold more negative stereotypes about mentally ill patients, but, reassuringly, they are less accepting of restrictions towards them."[217]

Recent depictions in media have included leading characters successfully living with and managing a mental illness, including in bipolar disorder in Homeland (2011) and post-traumatic stress disorder in Iron Man 3 (2013).[218][219][original research?]

Violence

Despite public or media opinion, national studies have indicated that severe mental illness does not independently predict future violent behavior, on average, and is not a leading cause of violence in society. There is a statistical association with various factors that do relate to violence (in anyone), such as substance use and various personal, social, and economic factors.[220] A 2015 review found that in the United States, about 4% of violence is attributable to people diagnosed with mental illness,[221] and a 2014 study found that 7.5% of crimes committed by mentally ill people were directly related to the symptoms of their mental illness.[222] The majority of people with serious mental illness are never violent.[223]

In fact, findings consistently indicate that it is many times more likely that people diagnosed with a serious mental illness living in the community will be the victims rather than the perpetrators of violence.[224][225] In a study of individuals diagnosed with "severe mental illness" living in a US inner-city area, a quarter were found to have been victims of at least one violent crime over the course of a year, a proportion eleven times higher than the inner-city average, and higher in every category of crime including violent assaults and theft.[226] People with a diagnosis may find it more difficult to secure prosecutions, however, due in part to prejudice and being seen as less credible.[227]

However, there are some specific diagnoses, such as childhood conduct disorder or adult antisocial personality disorder or

High-profile cases have led to fears that serious crimes, such as homicide, have increased due to deinstitutionalization, but the evidence does not support this conclusion.[229][230] Violence that does occur in relation to mental disorder (against the mentally ill or by the mentally ill) typically occurs in the context of complex social interactions, often in a family setting rather than between strangers.[231] It is also an issue in health care settings[232] and the wider community.[233]

Mental health

The recognition and understanding of mental health conditions have changed over time and across cultures and there are still variations in definition, assessment, and classification, although standard guideline criteria are widely used. In many cases, there appears to be a continuum between mental health and mental illness, making diagnosis complex.[41]: 39 According to the World Health Organization, over a third of people in most countries report problems at some time in their life which meet the criteria for diagnosis of one or more of the common types of mental disorder.[130] Corey M Keyes has created a two continua model of mental illness and health which holds that both are related, but distinct dimensions: one continuum indicates the presence or absence of mental health, the other the presence or absence of mental illness.[234] For example, people with optimal mental health can also have a mental illness, and people who have no mental illness can also have poor mental health.[235]

Other animals

The risk of anthropomorphism is often raised concerning such comparisons, and assessment of non-human animals cannot incorporate evidence from linguistic communication. However, available evidence may range from nonverbal behaviors—including physiological responses and homologous facial displays and acoustic utterances—to neurochemical studies. It is pointed out that human psychiatric classification is often based on statistical description and judgment of behaviors (especially when speech or language is impaired) and that the use of verbal self-report is itself problematic and unreliable.[236][238]

Psychopathology has generally been traced, at least in captivity, to adverse rearing conditions such as early separation of infants from mothers; early sensory deprivation; and extended periods of

Laboratory researchers sometimes try to develop

See also

- 50 Signs of Mental Illness

- List of mental disorders

- Mental illness portrayed in media

- Mental disorders in film

- Mental illness in fiction

- Mental illness in American prisons[globalize]

- Parity of esteem

- Psychological evaluation

References

- ^ "Applying for Disability Benefits with a Mental Illness". mhamd.org. Mental Health Association of Maryland.

- ^ a b Psychiatric Disabilities (PDF) (Report). Judicial Branch of California.

- ^ a b "Psychological Disabilities". ws.edu. Walters State Community College. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ "Mental illness – Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. 8 June 2019. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Any Mental Illness (AMI) Among U.S. Adults". National Institute of Mental Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ "Mental Disorders". Medline Plus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 15 September 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- JSTOR 2676305.

- ISBN 978-0-19-856592-5.

- PMID 24912469.

- ^ a b c d e f "Mental disorders". World Health Organization. 22 June 2022. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022.

- ^ "Mental disorders". World Health Organization. 2016. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ISBN 9780890425541.

- ^ PMID 28242200.

- ISBN 9780890425541.

- PMID 24331284.

- PMID 20624327.

In DSM-IV, each of the mental disorders is conceptualized as a clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndrome or pattern that occurs in an individual and that is associated with present distress (e.g., a painful symptom) or disability (i.e., impairment in one or more important areas of functioning) or with a significantly increased risk of suffering death, pain, disability, or an important loss of freedom. In addition, this syndrome or pattern must not be merely an expectable and culturally sanctioned response to a particular event, for example, the death of a loved one. Whatever its original cause, it must currently be considered a manifestation of behavioral, psychological, or biological dysfunction in the individual. Neither deviant behavior (e.g., political, religious, or sexual) nor conflicts that are primarily between the individual and society are mental disorders unless the deviance or conflict is a symptom of a dysfunction in the individual, as described above.

- PMID 20624327.

... although this manual provides a classification of mental disorders, it must be admitted that no definition adequately specifies precise boundaries for the concept of 'mental disorder.' The concept of mental disorder, like many other concepts in medicine and science, lacks a consistent operational definition that covers all situations. All medical conditions are defined on various levels of abstraction—for example, structural pathology (e.g., ulcerative colitis), symptom presentation (e.g., migraine), deviance from a physiological norm (e.g., hypertension), and etiology (e.g., pneumococcal pneumonia). Mental disorders have also been defined by a variety of concepts (e.g., distress, dyscontrol, disadvantage, disability, inflexibility, irrationality, syndromal pattern, etiology, and statistical deviation). Each is a useful indicator for a mental disorder, but none is equivalent to the concept, and different situations call for different definitions.

- ISBN 9780890425541.

- ^ "Chapter 6 on mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders". ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics, 2018 version.

- ISBN 978-0-19-853087-9.

- ^ PMID 9857496.

- ^ Hall-Flavin, Daniel K. (26 October 2016). "Nervous Breakdown" Mayo Clinic. Archived copy, 2 November 2021.

- ^ Healthdirect Australia (14 February 2019). "Nervous breakdown". www.healthdirect.gov.au. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-19-997825-0.[page needed]

- ]

- ]

- ^ "ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- S2CID 25866251.

- ^ Perring, C. (2005) Mental Illness Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- PMID 20148149.

- PMID 21991278.

- ^ Doward J (11 May 2013). "Medicine's big new battleground: does mental illness really exist?". The Guardian.

- ^ "Mental Disorders as Brain Disorders: Thomas Insel at TEDxCaltech". National Institute of Mental Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 23 April 2013. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013.

- PMID 27739389.

- PMID 25360393.

- PMID 27739384.

- PMID 27739393.

- PMID 28004947.

- ^ Gazzaniga, M.S., & Heatherton, T.F. (2006). Psychological Science. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.[page needed]

- ^ a b c "Mental Health: Types of Mental Illness". WebMD. 1 July 2005. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-16-050300-9.

- ^ Teacher's Guide: Information about Mental Illness and the Brain National Institute of Mental Health. 2005. Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine Curriculum supplement from The NIH Curriculum Supplements Series

- PMID 16488021.

- Wikidata Q47783989. Archived from the original(PDF) on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- S2CID 2728977.

- S2CID 15568151. Archived from the originalon 13 March 2023. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- PMID 11897231.

- ^ "Eating Disorders". National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). 2021. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ "Eating Disorders". National Institutes of Health. National Institute of Mental Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. December 2021. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Narcolepsy - Diagnosis and treatment". Mayo Clinic. 6 November 2022. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Sleep apnea - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. 20 July 2020. Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- S2CID 21221326.

- PMC 1738003.

- PMID 17551351.

- PMID 19002191.

- S2CID 208792724.

- PMID 11388966.

- PMID 16494258.

- S2CID 30881311.

- PMID 21734685.

- ^ Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation What is Psychiatric Disability and Mental Illness? Archived 4 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Boston University, Retrieved January 2012

- ^ ISBN 978-0-335-21583-6.[page needed]

- ^ Ferney, V. (2003) The Hierarchy of Mental Illness: Which diagnosis is the least debilitating? Archived 17 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine New York City Voices Jan/March

- PMID 18450663.

- S2CID 205962371.

- ^ Krastev, Nikola (2 February 2012). "CIS: UN Body Takes On Rising Suicide Rates – Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty 2006". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- ISBN 978-1-85433-290-5.

- PMID 16946849.

- S2CID 21703364.

- ^ a b c d e Risks to mental health. World Health Organization. 16 October 2012.

- PMID 11086146.

- PMID 20373672.

- ^ S2CID 95140.

- PMID 19339761.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association 3 May 2013 Release Number 13-33

- PMID 26913486.

- S2CID 22224892.

- PMID 9113138.

- ^ PMID 16150958.

- ^ PMID 26359904.

- ^ "The Report". The Schizophrenia Commission. 13 November 2012. Archived from the original on 5 April 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- S2CID 142581788.

- PMID 18606036.

- ^ a b c "Cannabis and mental health". Royal College of Psychiatrists. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- PMID 19255375.

- .

- S2CID 5364016.

- PMID 17626963.

- PMID 20104292.

- ^ "The Relationship between Mental Health, Mental Illness and Chronic Physical Conditions". Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), Ontario. Archived from the original on 16 July 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- S2CID 23548727.

- ^ PMID 23702592.

- PMID 22230881.

- S2CID 16787375.

- ^ Payne, Kattie. (2004). Mental Health Assessment. Archived 26 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine Yahoo! Health. Boise: Healthwise, Inc.

- PMID 9183204.

- PMID 12719503.

- PMID 10739417.

- ^ "What is HoNOS?". Royal College of Psychiatrists.

- ^ "Introduction to HoNOS". Royal College of Psychiatrists. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- PMID 16313678.

- PMID 11388975.

- ^ Caplan PJ (28 April 2012). "Psychiatry's bible, the DSM, is doing more harm than good". Opinions. Washington Post.

- PMID 23685989.

Unfortunately, the extensive research has had no effect on psychiatric diagnosis, which still relies exclusively on fallible subjective judgments rather than objective biological tests. … In the past 20 years, the rate of attention-deficit disorder tripled, the rate of bipolar disorder doubled, and the rate of autism increased more than 20-fold (4). The lesson should be clear that every change in the diagnostic system can lead to unpredictable overdiagnosis.

- ^ Kirk SA, Gomory T, Cohen D (2013). Mad Science: Psychiatric Coercion, Diagnosis, and Drugs. Transaction Publishers. p. 185.[ISBN missing]

- PMID 11950740.

- OCLC 827119919.

- ISBN 978-0-8156-0867-7.[page needed]

- PMID 30173550.

- ISBN 978-92-4-159215-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2004.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - S2CID 15874608.

- ^ Knapp M, McDaid D, Parsonage M, eds. (2 February 2011). "Mental health promotion and mental illness prevention: The economic case" (PDF). Personal Social Services Research Unit. London School of Economics and Political Science. Department of Health, London. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

as of 2019, it is now the Care Policy and Evaluation Centre

- ^ "Research Priorities for Strategic Objective 3". National Institute of Mental Health. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015.

- S2CID 234820994.

- S2CID 2548960.

- PMID 22079931.

- PMID 20192789.

- PMID 12900296.

- PMID 28303578.

- PMID 28942748.

- S2CID 27310867. Archived from the original(PDF) on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ The Joseph Rowntree Foundation (1998) The experiences of mental health service users as mental health professionals Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- S2CID 22521457.

- PMID 17064322.

- ^ "Mental Health Medications". National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Mind Disorders Encyclopedia Psychosurgery [Retrieved on 5 August 2008]

- S2CID 10303872.

- PMID 18208598.

- PMID 31672337.

- ^ PMID 10885160.

- ^ PMID 15939837.

- ^ "The World Mental Health Survey Initiative". Harvard School of Medicine. 2005.

- PMID 15173149.

- PMID 16989109.

- PMID 15065747.

- PMID 15939839.

- ^ "The Numbers Count: Mental Disorders in America". National Institute of Mental Health. 24 May 2013. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- S2CID 24499847.

- S2CID 26089761. Archived from the original(PDF) on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- PMID 15916472.

- PMID 11386989.

- S2CID 29235629.

- PMID 14959805.

- ^ "Gender disparities and mental health: The Facts". World Health Organization. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-29497-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8.

- OCLC 982958263.

- PMID 336681.

- ISBN 3-927408-82-4

- ^ Kirk SA, Kutchins H (1994). "The Myth of the Reliability of DSM". Journal of Mind and Behavior. 15 (1&2). Archived from the original on 7 March 2008.

- ^ "Mental illness: Invisible but devastating". Africa Renewal. 25 November 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "In West Africa, traditional or religious practices are often the preferred method of treating mental disorders". D+C. 12 June 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Why accessible, affordable treatment is vital to curbing rising mental health". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. 10 October 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "Mental health: Most Nigerians patronise traditional, spiritual healers – Expert". Daily Trust. 25 May 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- S2CID 28266198.

- ^ "Latinx/Hispanic Communities and Mental Health". Mental Health America.

- ^ Ramos-Olazagasti, Maria; Conway, C. Andrew. "The Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders Among Latino Parents". Hispanic Research Center.

- S2CID 248503963. "Disparities in behavioral health risk factors in the past decade have also grown and closely parallel the overall growth in the Latin American population (11–13). From 2015 to 2018, rates of serious mental illness in Latin American populations increased by 60% (from 4.0% to 6.4%) among those ages 18–25 years and by 77% (from 2.2% to 3.9%) among those ages 26–49 years (14). This report was based on analysis of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health and used the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA’s) definition of serious mental illness as a diagnosable mental, behavior, or emotional disorder that causes serious functional impairment that substantially interferes with one or more major life activities (15). A similar trend between 2015 and 2018 has been observed for the prevalence of major depressive episodes among Latin Americans ages 12–49 years, which increased from 8.4% to 11.3% (14). In a study based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, more than one-third (34%) of Latin American respondents reported at least one poor mental health day in the past month (mean=3.6 days), and 11% reported frequent mental distress (16)."

- ^ "Mental and Behavioral Health - Hispanics - The Office of Minority Health". minorityhealth.hhs.gov. "However, the suicide rate for [Latin Americans] is less than half that of the non-[Latin American] white population. In 2019, suicide was the second leading cause of death for Latin Americans, ages 15 to 34.1"

- ^ Pattani, Aneri. "Pandemic unveils growing suicide crisis for communities of color".

- ^ Despres, Cliff (9 March 2022). "More Latino Men Are Dying by Suicide, Even as the National Rate Declines". Salud America.

- PMID 24999521.

- ^ "Mental Health Stigma, Fueled by Religious Belief, May Prevent Many Latinos from Seeking Help". www.rutgers.edu.

- S2CID 22897500.

- S2CID 145541617.

- ISBN 978-0-470-97029-4.

- ^ S2CID 8949296.

- S2CID 207509518.

- S2CID 145793759.

- S2CID 13042932.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-157939-4.

- ^ Everett B (1994). "Something is happening: the contemporary consumer and psychiatric survivor movement in historical context". Journal of Mind and Behavior. 15 (1–2): 55–70.

- S2CID 19635873.

- PMID 16870979.

- ^ The Antipsychiatry Coalition. (26 November 2005). The Antipsychiatry Coalition. Retrieved 19 April 2007, from antipsychiatry.org[verification needed]

- PMID 11421968.

- PMID 15279009. Archived from the originalon 3 January 2014.

- PMID 20483977.

- ^ PMID 10751976.

- ^ Vedantam S (26 June 2005). "Psychiatry's Missing Diagnosis: Patients' Diversity Is Often Discounted". The Washington Post.

- S2CID 43256486.

- ISBN 9780865426740.[page needed]

- .

- PMID 15652693.

- S2CID 145545714.

- PMID 11264215.

- S2CID 53444644.

- S2CID 20638428.

- .

- ^ "TIP 59: Improving Cultural Competence | SAMHSA Publications and Digital Products". store.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ ]

- PMID 17696026.

- ^ Manitoba Family Services and Housing. The Vulnerable Persons Living with a Mental Disability Act, 1996[non-primary source needed]

- ^ Department of Economic and Social Affairs Disability

- ISBN 978-0-16-050300-9.

- PMID 27470237.

- PMID 30484715.

- ^ Lynsen A (24 September 2014). "Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- S2CID 26075592.

- ^ MedPartner Taiwan (22 May 2019). "別再說「想太多」!一張表看懂憂鬱症身心症狀". 健康遠見 (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- S2CID 45821626.

- ^ Lucas C. "Stigma hurts job prospects". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- Gale A106746772. Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ "Stop Stigma". Bipolarworld-net.canadawebhosting.com. 29 April 2002. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- S2CID 27738025.

- S2CID 19862722.

- ^ Edney, RD. (2004) Mass Media and Mental Illness: A Literature Review Archived 12 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine Canadian Mental Health Association

- .

- S2CID 145291023.

- S2CID 145696394.

- ^ "The Carter Center Awards 2008–2009 Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism" (Press release). The Carter Center. 18 July 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "The Rosalynn Carter Fellowships For Mental Health Journalism". The Carter Center. 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "Rosalynn Carter's Leadership in Mental Health". The Carter Center. 19 July 2016. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017.

- PMID 10474548.

- PMID 10474550.

- S2CID 19652980.

- S2CID 34916201.

- ^ Mitchell J (23 February 2018). "How 'Homeland' became a pioneer in the portrayal of mental illness". SBS. Australia.

- ^ Langley T (4 May 2013). "Does Iron Man 3's Hero Suffer Posttraumatic Stress Disorder?". Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- PMID 19188537.

- PMID 25496006.

- S2CID 2228512.

- PMID 24861430.

- ^ PMID 16946914.

- PMID 11585953.

- PMID 16061769.

- S2CID 145599816.

- PMID 9596041.

- ^ PMID 19668362.

- S2CID 24432329.

- S2CID 20067766.

- PMID 11779087.

- S2CID 12605241.

- PMID 20502508.

- ^ "What is Mental Health and Mental Illness? | Workplace Mental Health Promotion". Health Communication Unit. Workplace Mental Health Promotion. University of Toronto: Dalla Lana School of Public Health. 12 April 2010. Archived from the original on 1 August 2010.

- ^ S2CID 10101196.

- PMID 21698223.

- S2CID 20587935.

- PMID 10608560.

- .

- S2CID 25469071.

- S2CID 23468566.

Further reading

- Atkinson J (2006). Private and Public Protection: Civil Mental Health Legislation. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press. OCLC 475785132.

- Fried Y, Agassi J (1976). Paranoia: A Study in Diagnosis. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science. Vol. 50. Springer Dordrecht. ISSN 2214-7942.[publisher missing]

- Fried Y, Agassi J (1983). Psychiatry as Medicine. The Hague: Nijhoff. LCCN 83004224.

- Hicks JW (2005). ISBN 9780300106572.

- Hockenbury D, Hockenbury S (2004). Discovering Psychology. Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7167-5704-7.

- PMID 27631043.

- ISBN 0-19-280267-4. Archived from the originalon 18 March 2022.

- Radden J (20 February 2019). Mental Disorder (Illness).

- Weller MP, Eysenck M, eds. (1992). The Scientific Basis of Psychiatry (2nd ed.). London: W. B. Saunders. ISBN 0702014486.

- World Health Organization (2018). Management of physical health conditions in adults with severe mental disorders (PDF). Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. Geneva. ISBN 978-92-4-155038-3. Archived from the original (Guidelines) on 12 November 2020.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - Wiencke M (2006). "Schizophrenie als Ergebnis von Wechselwirkungen: Georg Simmels Individualitätskonzept in der Klinischen Psychologie". In Kim D (ed.). Georg Simmel in Translation: Interdisciplinary Border-Crossings in Culture and Modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press. pp. 123–55. ISBN 978-1-84718-060-5.

External links

- Overcoming Mental Health Stigma in the Latino Community – Consult QD clevelandclinic.org

- National Institute of Mental Health

- International Committee of Women Leaders on Mental Health Archived 30 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine