Mesoamerica

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and small parts of Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica.[1][2][3] [4]As a cultural area, Mesoamerica is defined by a mosaic of cultural traits developed and shared by its indigenous cultures.[5][2][6][7]

In the

Beginning as early as 7000 BCE, the domestication of

Among the earliest complex civilizations was the

In the subsequent Preclassic period, complex urban polities began to develop among the Maya,[11][12] with the rise of centers such as Aguada fénix and Calakmul in Mexico; El Mirador, and Tikal in Guatemala, and the Zapotec at Monte Albán. During this period, the first true Mesoamerican writing systems were developed in the Epi-Olmec and the Zapotec cultures. The Mesoamerican writing tradition reached its height in the Classic Maya logosyllabic script.

In Central Mexico, the city of

During the early post-Classic period, Central Mexico was dominated by the

The distinct Mesoamerican cultural tradition ended with the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. Eurasian diseases such as smallpox and measles, which were endemic among the colonists but new to North America, caused the deaths of upwards of 90% of the indigenous people, resulting in great losses to their societies and cultures.[14][15] Over the next centuries, Mesoamerican indigenous cultures were gradually subjected to Spanish colonial rule. Aspects of the Mesoamerican cultural heritage still survive among the indigenous peoples who inhabit Mesoamerica. Many continue to speak their ancestral languages and maintain many practices hearkening back to their Mesoamerican roots.[16]

Etymology and definition

- Ancient Mesoamerican sites in El Salvador

The term Mesoamerica literally means "middle America" in Greek. Middle America often refers to a larger area in the Americas, but it has also previously been used more narrowly to refer to Mesoamerica. An example is the title of the 16 volumes of The Handbook of Middle American Indians. "Mesoamerica" is broadly defined as the area that is home to the Mesoamerican civilization, which comprises a group of peoples with close cultural and historical ties. The exact geographic extent of Mesoamerica has varied through time, as the civilization extended North and South from its heartland in southern Mexico.

The term was first used by the

Some of the significant cultural traits defining the Mesoamerican cultural tradition are:[19]

- Horticulture and plant use: floating gardens; use of bark paper and agave (see also maguey) for ritual purposes, as a medium for writing, and the use of agave for cooking and clothing; cultivation of cacao; grinding of corn softened with ashes or lime; harpoon-shaped digging stick

- Clothing and personal articles: lip plugs, mirrors of polished stone, turbans, sandals with heels, textiles adorned with rabbit hair

- Architecture: construction of stepped pyramids; stucco floors; ball courts with stone rings (see the use of natural rubber and the practice of the ritual Mesoamerican ballgame)

- Record keeping: use of two different hieroglyphic (logo-syllabic) writing systems; numbers (see also vigesimal(base 20) number system); "century" of fifty-two years; eighteen-month calendar; screen-fold books

- Commerce: specialized markets, "department store" markets subdivided according to specialty

- Weapons and warfare: wooden swords with stone chips set into the edges (see macuahuitl), military orders (eagle knights and jaguar knights), clay pellets for blowguns, cotton-pad armor, traveling merchants who act as spies, wars for the purpose of securing sacrificial victims

- Ritual and myth: the practice of various forms of ritual sacrifice, including human sacrifice and quail sacrifice; paper and rubber as sacrificial offerings; a pantheon of gods or spirits; acrobatic flier dance (see the Danza de los Voladores and the Totonac flier dance; 13 as a ritual number; ritual period of 20 x 13 = 260 days; the mythic concept of one or more afterworlds and the difficult journey in reaching them; good and bad omen days; a religious complex based on a combination of shamanism and natural deities, and a shared system of symbols

- Language: a linguistic area defined by a number of grammatical traits that have spread through the area by diffusion[20]

Geography

Located on the

Cultural sub-areas

Several distinct sub-regions within Mesoamerica are defined by a convergence of geographic and cultural attributes. These sub-regions are more conceptual than culturally meaningful, and the demarcation of their limits is not rigid. The Maya area, for example, can be divided into two general groups: the lowlands and highlands. The lowlands are further divided into the southern and northern Maya lowlands. The southern Maya lowlands are generally regarded as encompassing northern Guatemala, southern Campeche and Quintana Roo in Mexico, and Belize. The northern lowlands cover the remainder of the northern portion of the Yucatán Peninsula. Other areas include Central Mexico, West Mexico, the Gulf Coast Lowlands, Oaxaca, the Southern Pacific Lowlands, and Southeast Mesoamerica (including northern Honduras).

Topography

There is extensive topographic variation in Mesoamerica, ranging from the high peaks circumscribing the

. Its peak elevation is 5,636 m (18,490 ft).The Sierra Madre mountains, which consist of several smaller ranges, run from northern Mesoamerica south through

One important topographic feature is the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a low plateau that breaks up the Sierra Madre chain between the Sierra Madre del Sur to the north and the Sierra Madre de Chiapas to the south. At its highest point, the Isthmus is 224 m (735 ft) above mean sea level. This area also represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean in Mexico. The distance between the two coasts is roughly 200 km (120 mi). The northern side of the Isthmus is swampy and covered in dense jungle—but the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, as the lowest and most level point within the Sierra Madre mountain chain, was nonetheless a main transportation, communication, and economic route within Mesoamerica.

Bodies of water

Outside of the northern Maya lowlands,

With an area of 8,264 km2 (3,191 sq mi),

Biodiversity

Almost all

Chronology and culture

The history of human occupation in Mesoamerica is divided into stages or periods. These are known, with slight variation depending on region, as the

The differentiation of early periods (i.e., up through the end of the

Paleo-Indian

The Mesoamerican Paleo-Indian period precedes the advent of agriculture and is characterized by a nomadic hunting and gathering subsistence strategy. Big-game hunting, similar to that seen in contemporaneous North America, was a large component of the subsistence strategy of the Mesoamerican Paleo-Indian. These sites had obsidian blades and Clovis-style fluted projectile points.

Archaic

The Archaic period (8000–2000 BCE) is characterized by the rise of

Preclassic/Formative

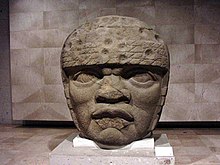

The first complex civilization to develop in Mesoamerica was that of the

During the Middle and Late Preclassic period, the

, among others.The Preclassic in the central Mexican highlands is represented by such sites as

In the

The Preclassic in western Mexico, in the states of Nayarit, Jalisco, Colima, and Michoacán also known as the Occidente, is poorly understood. This period is best represented by the thousands of figurines recovered by looters and ascribed to the "shaft tomb tradition".

Classic

Early Classic

The Classic period is marked by the rise and dominance of several polities. The traditional distinction between the Early and Late Classic is marked by their changing fortune and their ability to maintain regional primacy. Of paramount importance are Teotihuacán in central Mexico and Tikal in Guatemala; the Early Classic's temporal limits generally correlate to the main periods of these sites. Monte Albán in Oaxaca is another Classic-period polity that expanded and flourished during this period, but the Zapotec capital exerted less interregional influence than the other two sites.

During the Early Classic, Teotihuacan participated in and perhaps dominated a far-reaching macro-regional interaction network. Architectural and artifact styles (talud-tablero, tripod slab-footed ceramic vessels) epitomized at Teotihuacan were mimicked and adopted at many distant settlements. Pachuca obsidian, whose trade and distribution is argued to have been economically controlled by Teotihuacan, is found throughout Mesoamerica.

Tikal came to dominate much of the southern Maya lowlands politically, economically, and militarily during the Early Classic. An exchange network centered at Tikal distributed a variety of goods and commodities throughout southeast Mesoamerica, such as obsidian imported from central Mexico (e.g., Pachuca) and highland Guatemala (e.g.,

Late Classic

The Late Classic period (beginning c. 600 CE until 909 CE) is characterized as a period of interregional competition and factionalization among the numerous regional polities in the Maya area. This largely resulted from the decrease in Tikal's socio-political and economic power at the beginning of the period. It was therefore during this time that other sites rose to regional prominence and were able to exert greater interregional influence, including Caracol,

Terminal Classic

Generally applied to the Maya area, the Terminal Classic roughly spans the time between c. 800/850 and c. 1000 AD. Overall, it generally correlates with the rise to prominence of

Chichén Itzá was originally thought to have been a Postclassic site in the northern Maya lowlands. Research over the past few decades has established that it was first settled during the Early/Late Classic transition but rose to prominence during the Terminal Classic and Early Postclassic. During its apogee, this widely known site economically and politically dominated the northern lowlands. Its participation in the circum-peninsular exchange route, possible through its port site of Isla Cerritos, allowed Chichén Itzá to remain highly connected to areas such as central Mexico and Central America. The apparent "Mexicanization" of architecture at Chichén Itzá led past researchers to believe that Chichén Itzá existed under the control of a Toltec empire. Chronological data refutes this early interpretation, and it is now known that Chichén Itzá predated the Toltec; Mexican architectural styles are now used as an indicator of strong economic and ideological ties between the two regions.

Postclassic

The Postclassic (beginning 900–1000 CE, depending on area) is, like the Late Classic, characterized by the cyclical crystallization and fragmentation of various polities. The main Maya centers were located in the northern lowlands. Following Chichén Itzá, whose political structure collapsed during the Early Postclassic,

In central Mexico, the early portion of the Postclassic correlates with the rise of the

The

The Postclassic ends with the

, remained independent until 1697.Some Mesoamerican cultures never achieved dominant status or left impressive archaeological remains but are nevertheless noteworthy. These include the

Chronology in chart form

| Period | Timespan | Important cultures, cities |

|---|---|---|

Paleo-Indian

|

10,000–3500 BCE | Honduras, Guatemala, Belize, obsidian and pyrite points, Iztapan |

| Archaic | 3500–1800 BCE | Agricultural settlements, Tehuacán

|

| Preclassic (Formative) | 2000 BCE – 250 CE | Unknown culture in La Blanca and Ujuxte, Monte Alto culture |

| Early Preclassic | 2000–1000 BCE | San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan; Central Mexico: Chalcatzingo; Valley of Oaxaca: San José Mogote. The Maya area: Nakbe, Cerros

Central American Area: Los Naranjos |

| Middle Preclassic | 1000–400 BCE | Olmec area: |

| Late Preclassic | 400 BCE – 200 CE | Rio Azul; Central Mexico: Teotihuacan; Gulf Coast: Epi-Olmec culture; Western Mexico: Shaft Tomb Tradition

|

Classic

|

200–900 CE | Classic Maya Centers, Teotihuacan, Zapotec |

| Early Classic | 200–600 CE | Maya area: Tenampua

|

| Late Classic | 600–900 CE | Maya area: Teuchitlan tradition

|

| Terminal Classic | 800–900/1000 CE | Maya area: Puuc sites: Uxmal, Labna, Sayil, Kabah |

Postclassic

|

900–1519 CE | |

| Early Postclassic | 900–1200 CE | Kaminaljuyú, Joya de Cerén

|

| Late Postclassic | 1200–1521 CE | |

| Colonial | 1521–1821 | Amuzgo

|

| Postcolonial | 1821–present | Amuzgo

|

Other characteristics

Subsistence

By roughly 6000 BCE,

Mesoamerica lacked animals suitable for domestication, most notably domesticated large

Societies of this region did hunt certain wild species for food. These animals included deer, rabbit, birds, and various types of insects. They also hunted for luxury items, such as feline fur and bird plumage.[36]

Mesoamerican cultures that lived in the lowlands and coastal plains settled down in agrarian communities somewhat later than did highland cultures because there was a greater abundance of fruits and animals in these areas, which made a hunter-gatherer lifestyle more attractive.[32] Fishing also was a major provider of food to lowland and coastal Mesoamericans creating a further disincentive to settle down in permanent communities.

Political organization

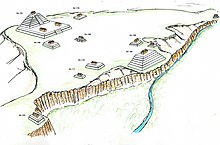

Ceremonial centers were the nuclei of Mesoamerican settlements. The temples provided spatial orientation, which was imparted to the surrounding town. The cities with their commercial and religious centers were always political entities, somewhat similar to the European city-state, and each person could identify with the city where they lived.[citation needed]

Ceremonial centers were always built to be visible. Pyramids were meant to stand out from the rest of the city, to represent the gods and their powers. Another characteristic feature of the ceremonial centers is historic layers. All the ceremonial edifices were built in various phases, one on top of the other, to the point that what we now see is usually the last stage of construction. Ultimately, the ceremonial centers were the architectural translation of the identity of each city, as represented by the veneration of their gods and masters.[

Economy

Given that Mesoamerica was broken into numerous and diverse ecological niches, none of the societies that inhabited the area were self-sufficient, although very long-distance trade was common only for very rare goods, or luxury materials.

The following is a list of some of the specialized resources traded from the various Mesoamerican sub-regions and environmental contexts:

- Pacific lowlands: cotton and cochineal

- Maya lowlands and the Gulf Coast: cacao, vanilla, jaguar skins, birds and bird feathers (especially quetzal and macaw)

- Central Mexico: Obsidian (Pachuca)

- Guatemalan highlands: Obsidian (San Martin Jilotepeque, El Chayal, and Ixtepeque), pyrite, and jade from the Motagua River valley

- Coastal areas: shell, and dyes

Architecture

Mesoamerican architecture is the collective name given to urban, ceremonial and public structures built by pre-Columbian civilizations in Mesoamerica. Although very different in styles, all kinds of Mesoamerican architecture show some kind of interrelation, due to very significant cultural exchanges that occurred during thousands of years. Among the most well-known structures in Mesoamerica, the flat-top pyramids are a landmark feature of the most developed urban centers.

Two characteristics are most notable in Mesoamerican architecture. Firstly, the intimate connection between geography, astronomy, and architecture: very often, urban centers or even single buildings are aligned to cardinal directions and/or along particular constellations.[38] Secondly, iconography was considered integral part of architecture, with buildings often being adorned with images of religious and cultural significance.[39]

Calendrical systems

Agriculturally based people historically divide the year into four seasons. These included the two

The Maya closely observed and duly recorded the seasonal markers. They prepared almanacs recording past and recent solar and

Among the many types of calendars the Maya maintained, the most important include a 260-day cycle, a 360-day cycle or 'year', a 365-day cycle or year, a lunar cycle, and a Venus cycle, which tracked the

The names given to the days, months, and years in the Mesoamerican calendar came, for the most part, from animals, flowers, heavenly bodies, and cultural concepts that held symbolic significance in Mesoamerican culture. This calendar was used throughout the history of Mesoamerican by nearly every culture. Even today, several Maya groups in Guatemala, including the

Writing systems

The Mesoamerican scripts deciphered to date are

The other

Mesoamerican writing is found in several mediums, including large stone monuments such as

The Mesoamerican book was typically written with brush and colored inks on a paper prepared from the inner bark of the Ficus amacus. The book consisted of a long strip of the prepared bark, which was folded like a screenfold to define individual pages. The pages were often covered and protected by elaborately carved book boards. Some books were composed of square pages while others were composed of rectangular pages.

Following the Spanish conquests in the sixteenth century, Spanish friars taught indigenous scribes to write their languages in alphabetic texts. Many oral histories of the prehispanic period were subsequently recorded in alphabetic texts. The indigenous in central and southern Mexico continued to produce written texts in the colonial period, many with pictorial elements. An important scholarly reference work is the

Arithmetic

Mesoamerican

In representing numbers, a series of bars and dots were employed. Dots had a value of one, and bars had a value of five. This type of arithmetic was combined with symbolic numerology: '2' was related to origins, as all origins can be thought of as doubling; '3' was related to household fire; '4' was linked to the four corners of the universe; '5' expressed instability; '9' pertained to the underworld and the night; '13' was the number for light, '20' for abundance, and '400' for infinity. The

Food, medicine, and science

Mesoamerica would deserve its place in the human

zero.[42]

Maize played an important role in Mesoamerican feasts due to its symbolic meaning and abundance.[43] Gods were praised and named after.

Companion planting was practiced in various forms by the indigenous peoples of the Americas. They domesticated squash 8,000 to 10,000 years ago, then maize, then common beans, forming the Three Sisters agricultural technique. The cornstalk served as a trellis for the beans to climb, and the beans fixed nitrogen, benefitting the maize.[44]

Fray

Evidence shows that wild animals were captured and traded for symbolic and ritual purposes.[49]

Mythology and worldview

The great breadth of the Mesoamerican

The typical Mesoamerican cosmology sees the world as separated into a day world watched by the sun and a night world watched by the moon. More importantly, the three superposed levels of the world are united by a Ceiba tree (Yaxche in Mayan). The geographic vision is also tied to the cardinal points. Certain geographical features are linked to different parts of this cosmovision. Thus mountains and tall trees connect the middle and upper worlds; caves connect the middle and nether worlds.

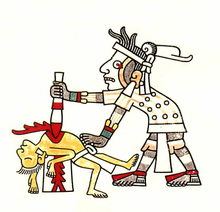

Sacrifice

Generally, sacrifice can be divided into two types:

Autosacrifice

Autosacrifice, also called

Autosacrifice was not limited to male rulers, as their female counterparts often performed these ritualized activities. They are typically shown performing the rope and thorns technique. A recently discovered queen's tomb in the Classic Maya site of Waka (also known as El Perú) had a ceremonial stingray spine placed in her genital area, suggesting that women also performed bloodletting in their genitalia.[54]

Human sacrifice

Sacrifice had great importance in the social and religious aspects of Mesoamerican culture. First, it showed death transformed into the divine.[55] Death is the consequence of a human sacrifice, but it is not the end; it is but the continuation of the cosmic cycle. Death creates life—divine energy is liberated through death and returns to the gods, who are then able to create more life. Secondly, it justifies war, since the most valuable sacrifices are obtained through conflict. The death of the warrior is the greatest sacrifice and gives the gods the energy to go about their daily activities, such as the bringing of rain. Warfare and capturing prisoners became a method of social advancement and a religious cause. Finally, it justifies the control of power by the two ruling classes, the priests and the warriors. The priests controlled the religious ideology, and the warriors supplied the sacrifices. Historically, it was also believed those sacrificed were chosen by the gods, this idea of being "chosen" was decided by the gods. This was then displayed by acts, such as being struck by lightning. If someone was struck by lightning and a sacrifice was needed they would often be chosen by their population, as they believed they were chosen by the gods.

Ballgame

The Mesoamerican ballgame was a sport with ritual associations played for over 3000 years by nearly all pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a modern version of the game, ulama, is still played in a few places.

Over 1300 ballcourts have been found throughout Mesoamerica.[56] They vary considerably in size, but they all feature long narrow alleys with side walls to bounce the balls against.

The rules of the ballgame are not known, but it was probably similar to volleyball, where the object is to keep the ball in play. In the most well-known version of the game, the players struck the ball with their hips, though some versions used forearms or employed rackets, bats, or handstones. The ball was made of solid rubber, and weighed up to 4 kg or more, with sizes that differed greatly over time or according to the version played.[57][58]

While the game was played casually for simple recreation, including by children and perhaps even women, the game also had important ritual aspects, and major formal ballgames were held as ritual events, often featuring human sacrifice.

Astronomy

Mesoamerican astronomy included a broad understanding of the cycles of planets and other celestial bodies. Special importance was given to the sun, moon, and Venus as the morning and evening star.[59]

Observatories were built at some sites, including the round observatory at Ceibal and the "Observatorio" at Xochicalco. Often, the architectural organization of Mesoamerican sites was based on precise calculations derived from astronomical observations. Well-known examples of these include the El Castillo pyramid at Chichen Itza and the Observatorio at Xochicalco. A unique and common architectural complex found among many Mesoamerican sites is the E-Group; these are aligned to serve as astronomical observatories. The name of this complex is based on Uaxactun's "Group E", the first known observatory in the Maya area. Perhaps the earliest observatory documented in Mesoamerica is that of the Monte Alto culture. This complex consisted of three plain stelae and a temple oriented with respect to the Pleiades.[60]

Symbolism of space and time

It has been argued that among Mesoamerican societies the concepts of

Dates or events were always tied to a compass direction, and the calendar specified the symbolic geographical characteristic peculiar to that period. Resulting from the significance held by the cardinal directions, many Mesoamerican architectural features, if not entire settlements, were planned and oriented according to directionality.In Maya cosmology, each cardinal point was assigned a specific color and a specific jaguar deity (Bacab). They are as follows:

- Hobnil, Bacab of the East, associated with the color red and the Kan years

- Can Tzicnal, Bacab of the North, assigned the color white and the Muluc years

- Zac Cimi, Bacab of the West, associated with the color black and the Ix years

- Hozanek, Bacab of the South, associated with the color yellow and the Cauac years.

Later cultures such as the

Among the Aztecs, the name of each day was associated with a cardinal point (thus conferring symbolic significance), and each cardinal direction was associated with a group of symbols. Below are the symbols and concepts associated with each direction:

- East: serpent, water, cane, and movement. The East was linked to the world priests and associated with vegetative fertility, or, in other words, tropical exuberance.

- North: wind, death, the dog, the jaguar, and flint (or chert). The North contrasts with the East in that it is conceptualized as dry, cold, and oppressive. It is considered the nocturnal part of the universe and includes the dwellings of the dead. The dog (xoloitzcuintle) has a very specific meaning, as it accompanies the deceased during the trip to the lands of the dead and helps them cross the river of death that leads to nothingness. (See also Dogs in Mesoamerican folklore and myth).

- West: the house, the deer, the monkey, the eagle, and rain. The west was associated with the cycles of vegetation, specifically the temperate high plains that experience light rains and the change of seasons.

- South: rabbit, the lizard, dried herbs, the buzzard, and flowers. It is related on the one hand to the luminous Sun and the noon heat, and on the other to rain filled with alcohol. The rabbit, the principal symbol of the West, was associated with farmers and with pulque.

Political and religious art

Mesoamerican

The majority of artwork created during this historical time was about these topics, religion and politics. Rulers were drawn and sculpted. Historical tales and events were then translated into pieces of art, and art was used to relay religious and political messages.

Music

Archaeological studies have never discovered any written music from the pre-Columbian era, but musical instruments were found, as well as carvings and depictions, that clearly show how music played a central role in the Mayan religious and societal structures, for example, as accompaniment to celebrations and funerals.[62] Some Mesoamerican civilizations, such as the Maya, commonly played various instruments such as drums, flutes and whistles.[63] Although most of the original Mayan music disappeared following the Spanish colonization, some of it mixed with the incoming Spanish music and exists to date.

See also

- Americas (terminology)

- Americas

- Central America

- Hispanic America

- Hispanic and Latino Americans

- Indigenous peoples of Mexico

- Indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Latin America

- Mesoamerican region

- Middle America (Americas)

- Painting in the Americas before European colonization

References

- ^ "Mesoamerica". Education | National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on Dec 30, 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4443-3884-3.

- ^ Kilroy-Ewbank, Lauren. "Mesoamerica, an introduction". Art of the Americas to World War I. Khan Academy. Archived from the original on Nov 7, 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-19-976658-1, retrieved 2024-04-14

- ^ Kilroy-Ewbank, Lauren (September 12, 2017). "Mesoamerica, an introduction". Smarthistory. Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- ISBN 978-0-19-976658-1, retrieved 2024-04-14

- ISBN 978-0-19-976656-7, retrieved 2024-04-14

- ^ Carrasco 2001.

- ^ Fagan 1996, p. 762.

- ^ Carmack, Gasco & Gossen 1996, p. 55.

- ^ "Exploring the Maya World". Google Arts & Culture. Archived from the original on Jan 25, 2024.

- ^ "Who Are the Maya?". Google Arts & Culture.

- ^ Carmack, Gasco & Gossen 1996, pp. 40–80.

- ISBN 0-19-860652-4) Oxford: Oxford University Press; p. 906.

- ^ (2000): Atlas del México Prehispánico. Revista Arqueología mexicana. Número especial 5. Julio de 2000. Raíces/ Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. México.

- ^ Carmack, Gasco & Gossen 1996, p. [page needed].

- ^ Kirchhoff 1943.

- ^ Carmack, Gasco & Gossen 1996, pp. 5–8.

- ISBN 0688067212.

- ^ Campbell, Kaufman & Smith-Stark 1986.

- ^ Coe 1994.

- ^ Carmack, Gasco & Gossen 1996, pp. 9–11.

- ^ "MTU Volcanoes Page – World Reference Map". Geo.mtu.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-04-08. Retrieved 2014-04-21.

- doi:10.1101/684431.

- ^ "Science Show – Bosawas Bioreserve Nicaragua". Abc.net.au. 2006-08-19. Archived from the original on 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2014-04-21.

- (PDF) from the original on 2018-05-18. Retrieved 2018-05-17.

- S2CID 158673509.

- ^ Diehl 2004, p. 248.

- ^ Paul A. Dunn; Vincent H. Malmström. "Pre-Columbian Magnetic Sculptures in Western Guatemala" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-09. Retrieved 2006-12-31. (10.1 KB)

- ^ "the kingdom of this world".

- ^ "Los Ladrones cave site" (PDF). UAC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-15. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ a b O'Brien 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Diamond 1999, p. 126–27.

- ^ Diamond 1999, p. 100.

- ^ Coe (1994), p. 45 ("The only domestic animals were dogs—the principal source of meat for much of Preclassic Mesoamerica—and turkeys—understandably rare because that familiar bird consumes very large quantities of corn and is thus expensive to raise".)

- ^ Diamond 1999.

- ^ "Science, civilization and society". www.mt-oceanography.info. Archived from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- ^ Šprajc, Ivan. "El Sol en Chichén Itzá y Dzibilchaltún: la supuesta importancia de los equinoccios en Mesoamérica". Arqueología Mexicana.

- ^ Miller & Taube 1993, p. 30.

- ^ Roxanne V. Pacheco, Myths of Mesoamerican Cultures Reflect a Knowledge and Practice of Astronomy, University of New Mexico, archived July 18, 2003 (accessed January 25, 2016).

- ^ Bernardino de Sahagun, Historia de las cosas de Nueva Espana; Diego Duran, The Book of The Gods and Rites, Oklahoma; The Books of Chilam Balam of Mani, Kaua, and Chumayel.

- ^ Mann, Charles C. 1491: Revelations of the Americas before Columbus. Vinton Press. 2005. pp. 196–97.

- ^ Lecount, Lisa J. "Like Water for Chocolate: Feasting and Political Ritual among the Late Classic Maya at Xunantunich, Belize." American Anthropologist 103.4 (2001): 935–53. Web.

- ^ Landon, Amanda J. (2008). "The "How" of the Three Sisters: The Origins of Agriculture in Mesoamerica and the Human Niche". Archived from the original on 2021-04-14.

- OCLC 6251390.

- ^ de Sahagún, Bernardino (1577). General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: The Florentine Codex. Archived from the original on 2020-12-02. Retrieved 2020-12-16 – via World Digital Library.

- ^ Hofmann, Albert (1971). "Teonanácatl and Ololiuqui, two ancient magic drugs of Mexico". Bulletin on Narcotics.

- PMID 21893367.

- ^ Sugiyama, Fash & France 2018.

- ^ Ortiz de Montellano 1990, p. 67-71.

- ^ "Transcript of "The Maya myth of the morning star"". www.ted.com. 21 October 2019. Archived from the original on 2021-08-17. Retrieved 2021-02-04.

- ^ "Creation Story of the Maya | Living Maya Time". maya.nmai.si.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-01-20. Retrieved 2021-02-04.

- ^ "Feeding the gods: Hundreds of skulls reveal massive scale of human sacrifice in Aztec capital". Science | AAAS. 2018-06-21. Archived from the original on 2021-10-13. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- ^ "Archaeologists Announce Discoveries At The Ancient Maya Site Of Waka' In Northern Guatemala". May 6, 2004. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ Fitzsimmons 2009.

- American Southwest. This total does not include those, since they are outside Mesoamerica, and there is discussion whether these areas were actually used for ballplaying.

- ^ Filloy Nadal 2001, p. 30.

- ^ Leyenaar 2001, pp. 125–26.

- ^ Grofe 2016, p. 1-12.

- ^ Šprajc 2011, p. 87-95.

- ^ Duverger 1999.

- ISBN 978-0-292-71319-2.

- from the original on 2021-04-10. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

Bibliography

- Adams, Richard E. W.; MacLeod, Murdo J., eds. (2000). Cambridge History of the Native peoples of The Americas. Vol. 2: Mesoamerica. Cambridge University Press.

- Braswell, Geoffrey E. (2003). "Introduction: Reinterpreting Early Classic Interaction". In Geoffrey E. Braswell (ed.). The Maya and Teotihuacan: Reinterpreting Early Classic Interaction. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 1–44. OCLC 49936017.

- OCLC 32923907.

- OCLC 1361911.

- Carmack, Robert M.; Gasco, Janine L.; Gossen, Gary H. (1996). Legacy of Mesoamerica, The: History and Culture of a Native American Civilization. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-337445-2.

- OCLC 1169898498. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-09.

- Carrasco, Davíd; Jones, Lindsay; Sessions, Scott (2002). Mesoamerica's Classic Heritage: From Teotihuacan to the Aztecs. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

- ISBN 978-0-500-27722-5.

- Diehl, Richard A. (2004). The Olmecs: America's First Civilization. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28503-9.

- ISBN 978-0-393-31755-8.

- Duverger, Ch. (1999). La Méso-Amérique: L'art pré-hispanique du Mexique et de l'Amérique centrale (in French). Paris: Flammarion.

- Fagan, Brian M., ed. (1996). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507618-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-10-16. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- Filloy Nadal, Laura (2001). "Rubber and Rubber Balls in Mesoamerica". In E. Michael Whittington (ed.). The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame. New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 20–31. ISBN 978-0-500-05108-5.

- Fitzsimmons, James L. (2009). Death And The Classic Maya Kings, Chapter Three Royal Funerals. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-79370-5.

- Gamio, Manuel (1922). La Población del Valle de Teotihuacán: Representativa de las que Habitan las Regiones Rurales del Distrito Federal y de los Estados de Hidalgo, Puebla, México y Tlaxcala (in Spanish). Mexico City: Talleres Gráficos de la Secretaría de Educación Pública. 2 vols. in 3.

- Gibson, Charles. The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1964.

- Grofe, Michael J. (2016), "Astronomy in Mesoamerica", in Selin, Helaine (ed.), Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 1–12, ISBN 978-94-007-3934-5

- Kirchhoff, Paul (1943). "Mesoamérica. Sus Límites Geográficos, Composición Étnica y Caracteres Culturales". Acta Americana (in Spanish). 1 (1): 92–107.

- Leyenaar, Ted (2001). "The Modern Ballgames of Sinaloa: a Survival of the Aztec Ullamaliztli". In E. Michael Whittington (ed.). The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame. New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 97–115. ISBN 978-0-500-05108-5.

- OCLC 24283718.

- López Austin, Alfredo; López Luján, Leonardo (1996). El pasado indígena (in Spanish). Mexico City: El Colegio de México. ISBN 978-968-16-4890-9.

- O'Brien, Patrick, ed. (2005). Oxford Atlas of World History. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Markman, Roberta H.; Markman, Peter T. (1992). The Flayed God: the Mesoamerican Mythological Tradition; Sacred Texts and Images from pre-Columbian Mexico and Central America. San Francisco: OCLC 25507756.

- OCLC 27667317.

- Mendoza, Ruben G. (2001). Mesoamerican Chronology: Periodization. Vol. 2. pp. 222–226. )

- Ortiz de Montellano, B. (1990). Aztec medicine, health, and nutrition. Mazal Holocaust Collection. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. OCLC 20798977.

- Palerm, Ángel (1972). Agricultura y civilización en Mesoamérica (in Spanish). Mexico: Secretaría de Educación Pública. ISBN 978-968-13-0994-7.

- OCLC 56695639.

- OCLC 276351.

- Sharer, Robert J.; Traxler, Loa P. (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th ed.). Stanford University Press.

- OCLC 48579073.

- (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-08. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- Smith, Michael E.; Masson, Marilyn (2000). The Ancient Civilizations of Mesoamerica: A Reader. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Šprajc, Ivan (June 2011). "Astronomy and its role in ancient Mesoamerica". The Role of Astronomy in Society and Culture. 260: 87–95. ISSN 1743-9221.

- Suaréz, Jorge A. (1983). The Mesoamerican Indian Languages. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge: OCLC 8034800.

- Sugiyama, Nawa; Fash, William L.; France, Christine A. M. (2018). "Jaguar and puma captivity and trade among the Maya: Stable isotope data from Copan, Honduras". PLOS ONE. 13 (9): e0202958. PMID 30208053.

- Taladoire, Eric (2001). "The Architectural Background of the Pre-Hispanic Ballgame". In E. Michael Whittington (ed.). The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame. New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 97–115. ISBN 978-0-500-05108-5.

- Wauchope, Robert, general editor. Handbook of Middle American Indians. Austin: University of Texas Press 1964–1976.

- Weaver, Muriel Porter (1993). The Aztecs, Maya, and Their Predecessors: Archaeology of Mesoamerica (3rd ed.). San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-01-263999-3.

- Zeitlin, Robert N.; Zeitlin, Judith (2000). The Paleoindian and Archaic Cultures of Mesoamerica. Vol. 2. pp. 45–122. )

External links

- Maya Culture

- Mesoweb.com: a comprehensive site for Mesoamerican civilizations

- Museum of the Templo Mayor (Mexico) (in Spanish)

- National Museum of Anthropology and History (Mexico) (in Spanish)

- Selected bibliography concerning war in Mesoamerica (in Spanish)

- WAYEB: European Association of Mayanists

- Arqueologia Iberoamericana: Open access international scientific journal devoted to the archaeological study of the American and Iberian peoples. It contains research articles on Mesoamerica.

- Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520–1820

- "Google Scholar Citations: Mesoamerica".