Metalloprotein

Metalloprotein is a generic term for a protein that contains a metal ion cofactor.[1][2] A large proportion of all proteins are part of this category. For instance, at least 1000 human proteins (out of ~20,000) contain zinc-binding protein domains[3] although there may be up to 3000 human zinc metalloproteins.[4]

Abundance

It is estimated that approximately half of all proteins contain a metal.[5] In another estimate, about one quarter to one third of all proteins are proposed to require metals to carry out their functions.[6] Thus, metalloproteins have many different functions in cells, such as storage and transport of proteins, enzymes and signal transduction proteins, or infectious diseases.[7] The abundance of metal binding proteins may be inherent to the amino acids that proteins use, as even artificial proteins without evolutionary history will readily bind metals.[8]

Most metals in the human body are bound to proteins. For instance, the relatively high concentration of iron in the human body is mostly due to the iron in hemoglobin.

| Liver | Kidney | Lung | Heart | Brain | Muscle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn (manganese) | 138 | 79 | 29 | 27 | 22 | <4-40 |

| Fe (iron) | 16,769 | 7,168 | 24,967 | 5,530 | 4,100 | 3,500 |

| Co (cobalt) | <2-13 | <2 | <2-8 | --- | <2 | 150 (?) |

| Ni (nickel) | <5 | <5-12 | <5 | <5 | <5 | <15 |

| Cu (copper) | 882 | 379 | 220 | 350 | 401 | 85-305 |

| Zn (zinc) | 5,543 | 5,018 | 1,470 | 2,772 | 915 | 4,688 |

Coordination chemistry principles

In metalloproteins, metal ions are usually coordinated by

In addition to donor groups that are provided by amino acid residues, many organic

protein. Inorganic ligands such as sulfide and oxide are also common.Storage and transport metalloproteins

These are the second stage product of protein hydrolysis obtained by treatment with slightly stronger acids and alkalies.

Oxygen carriers

In both

2.[14][15]

Cytochromes

Cytochrome P450 enzymes perform the function of inserting an oxygen atom into a C−H bond, an oxidation reaction.[18][19]

Rubredoxin

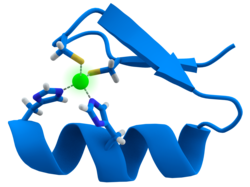

Plastocyanin

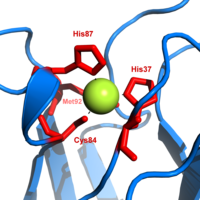

Plastocyanin is one of the family of blue

In the reduced form of plastocyanin, His-87 will become protonated with a pKa of 4.4. Protonation prevents it acting as a ligand and the copper site geometry becomes trigonal planar.

Metal-ion storage and transfer

Iron

Iron is stored as iron(III) in ferritin. The exact nature of the binding site has not yet been determined. The iron appears to be present as a hydrolysis product such as FeO(OH). Iron is transported by transferrin whose binding site consists of two tyrosines, one aspartic acid and one histidine.[22] The human body has no mechanism for iron excretion.[citation needed] This can lead to iron overload problems in patients treated with blood transfusions, as, for instance, with β-thalassemia. Iron is actually excreted in urine[23] and is also concentrated in bile[24] which is excreted in feces.[25]

Copper

Ceruloplasmin is the major copper-carrying protein in the blood. Ceruloplasmin exhibits oxidase activity, which is associated with possible oxidation of Fe(II) into Fe(III), therefore assisting in its transport in the blood plasma in association with transferrin, which can carry iron only in the Fe(III) state.

Calcium

Osteopontin is involved in mineralization in the extracellular matrices of bones and teeth.

Metalloenzymes

Metalloenzymes all have one feature in common, namely that the metal ion is bound to the protein with one

Carbonic anhydrase

In aqueous solution, carbon dioxide forms carbonic acid

- CO2 + H2O ⇌ H2CO3

This reaction is very slow in the absence of a catalyst, but quite fast in the presence of the hydroxide ion

- CO2 + OH− ⇌ HCO−

3

A reaction similar to this is almost instantaneous with

- H2CO3 ⇌ HCO−

3 + H+

favours dissociation of carbonic acid at biological pH values.[26]

Vitamin B12-dependent enzymes

The

Nitrogenase (nitrogen fixation)

The

where Pi stands for inorganic phosphate. The precise structure of the active site has been difficult to determine. It appears to contain a MoFe7S8 cluster that is able to bind the dinitrogen molecule and, presumably, enable the reduction process to begin.[30] The electrons are transported by the associated "P" cluster, which contains two cubical Fe4S4 clusters joined by sulfur bridges.[31]

Superoxide dismutase

The

The formal oxidation state of the oxygen atoms is −1⁄2. In solutions at neutral pH, the superoxide ion disproportionates to molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide.

- 2 O−

2 + 2 H+ → O2 + H2O2

In biology this type of reaction is called a

- Oxidation: M(n+1)+ + O−

2 → Mn+ + O2 - Reduction: Mn+ + O−

2 + 2 H+ → M(n+1)+ + H2O2.

In human SOD, the active metal is copper, as Cu(II) or Cu(I), coordinated tetrahedrally by four histidine residues. This enzyme also contains zinc ions for stabilization and is activated by copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase (CCS). Other isozymes may contain iron, manganese or nickel. The activity of Ni-SOD involves nickel(III), an unusual oxidation state for this element. The active site nickel geometry cycles from square planar Ni(II), with thiolate (Cys2 and Cys6) and backbone nitrogen (His1 and Cys2) ligands, to square pyramidal Ni(III) with an added axial His1 side chain ligand.[34]

Chlorophyll-containing proteins

Chlorophyll plays a crucial role in photosynthesis. It contains a magnesium enclosed in a chlorin ring. However, the magnesium ion is not directly involved in the photosynthetic function and can be replaced by other divalent ions with little loss of activity. Rather, the photon is absorbed by the chlorin ring, whose electronic structure is well-adapted for this purpose.

Initially, the absorption of a photon causes an

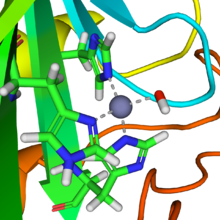

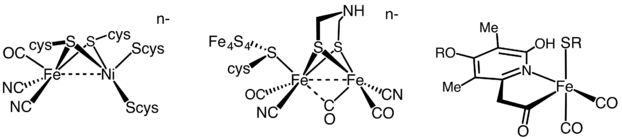

Hydrogenase

Hydrogenases are subclassified into three different types based on the active site metal content: iron–iron hydrogenase, nickel–iron hydrogenase, and iron hydrogenase.[35] All hydrogenases catalyze reversible H2 uptake, but while the [FeFe] and [NiFe] hydrogenases are true redox catalysts, driving H2 oxidation and H+ reduction

- H2 ⇌ 2 H+ + 2 e−

the [Fe] hydrogenases catalyze the reversible heterolytic cleavage of H2.

- H2 ⇌ H+ + H−

Ribozyme and deoxyribozyme

Since discovery of ribozymes by Thomas Cech and Sidney Altman in the early 1980s, ribozymes have been shown to be a distinct class of metalloenzymes.[36] Many ribozymes require metal ions in their active sites for chemical catalysis; hence they are called metalloenzymes. Additionally, metal ions are essential for structural stabilization of ribozymes. Group I intron is the most studied ribozyme which has three metals participating in catalysis.[37] Other known ribozymes include group II intron, RNase P, and several small viral ribozymes (such as hammerhead, hairpin, HDV, and VS) and the large subunit of ribosomes. Several classes of ribozymes have been described.[38]

Signal-transduction metalloproteins

Calmodulin

In an

The protein has two approximately symmetrical domains, separated by a flexible "hinge" region. Binding of calcium causes a conformational change to occur in the protein. Calmodulin participates in an intracellular signaling system by acting as a diffusible second messenger to the initial stimuli.[45][46]

Troponin

In both

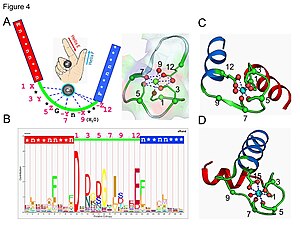

Transcription factors

Many transcription factors contain a structure known as a zinc finger, this is a structural module where a region of protein folds around a zinc ion. The zinc does not directly contact the DNA that these proteins bind to. Instead, the cofactor is essential for the stability of the tightly folded protein chain.[47] In these proteins, the zinc ion is usually coordinated by pairs of cysteine and histidine side-chains.

Other metalloenzymes

There are two types of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase: one contains iron and molybdenum, the other contains iron and nickel. Parallels and differences in catalytic strategies have been reviewed.[48]

Pb2+ (lead) can replace Ca2+ (calcium) as, for example, with

Some other metalloenzymes are given in the following table, according to the metal involved.

| Ion | Examples of enzymes containing this ion |

|---|---|

| Magnesium[50] | Glucose 6-phosphatase Hexokinase DNA polymerase Poly(A) polymerase

|

| Vanadium | vanabins

|

| Manganese[51] | Arginase Oxygen-evolving complex |

| Iron[52] | IRE-BP

Aconitase |

| Cobalt[53] | Nitrile hydratase Methionyl aminopeptidase Methylmalonyl-CoA mutase Isobutyryl-CoA mutase |

| Nickel[54][55] | Methyl-coenzyme M reductase (MCR)

|

| Copper[56] | |

| Zinc[57] | Beta amyloid

|

| Cadmium[58][59] | Thiolate proteins

|

| Molybdenum[60] | Nitrate reductase Sulfite oxidase Xanthine oxidase DMSO reductase |

| Tungsten[61] | Acetylene hydratase |

| various | Metallothionein Phosphatase |

See also

References

- PMID 23595668.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-850330-9.

- ^ Human reference proteome in Uniprot, accessed 12 Jan 2018

- PMID 17081069.

- PMID 9667942.

- S2CID 7253420.

- PMID 24470087.

- PMID 30634485.

- PMID 21069142.

- PMID 28731303.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8. Fig.25.7, p 1100 illustrates the structure of deoxyhemoglobin

- .

- PMID 12656634.

- .

- .

- ISBN 978-0-471-62743-2.

- ^ Moore GR, Pettigrew GW (1990). Cytochrome c: Structural and Physicochemical Aspects. Berlin: Springer.

- ISBN 978-0-470-01672-5.

- ISBN 978-0-306-48324-0.

- S2CID 4226644.

- )

- PMID 3470756.

- PMID 8808191.

- S2CID 7925719.

- ^ "Biliary excretion of waste products". Archived from the original on 2017-03-26. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- PMID 9336012.

- ISBN 978-1-84755-915-9.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1964". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- S2CID 95235740.

- ISBN 9780841227088.

- PMID 8484118.

- ISBN 978-0-12-182252-1.

- ISBN 978-3-540-32680-9.

- PMID 15209499.

- ^

Parkin, Alison (2014). "Understanding and Harnessing Hydrogenases, Biological Dihydrogen Catalysts". In Kroneck, Peter M. H.; Sosa Torres, Martha E. (eds.). The Metal-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 14. Springer. pp. 99–124. PMID 25416392.

- PMID 7688142.

- PMID 10535916.

- PMID 26167874.

- PMID 9383394.

- PMID 25939889.

- PMID 9113977.

- PMID 9383394.

- PMID 17284609.

- PMID 25918425.

- PMID 6313166.

- PMID 10884684.

- PMID 2114117.

- PMID 25416390.

- PMID 28731300.

- PMID 23595671.

- PMID 23595673.

- PMID 23595675.

- )

- ISBN 978-0-470-01671-8.

- )

- )

- )

- PMID 23430777.

- PMID 23430778.

- )

- PMID 25416389.

External links

- Metalloprotein at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Catherine Drennan's Seminar: Snapshots of Metalloproteins