Meteorological history of Hurricane Patricia

Track of Hurricane Patricia | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 20, 2015 |

| Dissipated | October 24, 2015 |

| Category 5 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 215 mph (345 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 872 mbar (hPa); 25.75 inHg (Record low in Western Hemisphere; second-lowest globally) |

| Overall effects | |

| Areas affected |

|

Part of the 2015 Pacific hurricane season | |

On October 23, two

Origins

On October 11, 2015, an area of disturbed weather traversed Central America and emerged over the eastern Pacific Ocean.

Moving south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec on October 18, the system consolidated and developed a small, defined circulation.

Rapid intensification

Located south of a

Exceptionally favorable atmospheric conditions, consisting of little

Forecast errors

| Forecast period |

Patricia errors | 2010–14 errors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kn | mph | km/h | kn | mph | km/h | |

| 12 hours | 22.7 | 26.1 | 42.0 | 5.9 | 6.8 | 10.9 |

| 24 hours | 35.0 | 40.3 | 64.8 | 9.8 | 11.3 | 18.1 |

| 36 hours | 47.7 | 58.9 | 88.3 | 12.5 | 14.4 | 23.2 |

| 48 hours | 57.8 | 66.5 | 107.0 | 14.0 | 16.1 | 25.9 |

| 72 hours | 55.0 | 63.3 | 101.9 | 15.5 | 17.8 | 28.7 |

| 96 hours | 25.0 | 28.8 | 46.3 | 16.3 | 18.8 | 30.2 |

The rapid intensification of Patricia was well-anticipated but poorly forecast. Meteorologists at the NHC indicated the possibility of such in the system's first advisory as a tropical depression. They noted the only inhibiting factor would be how quickly the storm could organize an inner core.[12] Just before the onset of rapid intensification, the agency was unable to utilize the Statistical Hurricane Intensity Prediction Scheme rapid intensification guidance due to technical errors. This likely contributed to even greater errors in the agency's forecast.[2] Initial forecasts were consistently conservative with intensity and dramatic strengthening was not explicitly shown until rapid intensification was already underway.[2]

At 03:00 UTC on October 22, the NHC forecast Patricia to achieve major hurricane status in 36 hours;[14] less than 15 hours later, the system exceeded their forecast peak.[2] Strengthening into a Category 5 hurricane was not forecast at all until Patricia had already reached such intensity,[15][16] although in the intermediate advisory immediately before Patricia's upgrade to Category 5, the NHC noted that "Patricia could become a category 5 hurricane overnight",[17] and in the preceding tropical weather discussion, noted that "Patricia could ... reach Category 5 intensity".[18] This trend continued throughout the rapid intensification period, resulting in some of the largest errors on record through 48 hours; they were the worst-ever for the Eastern Pacific since the NHC took over operations for the basin in 1988. All forecast models saw enormous errors, most of which performed worse than the official NHC forecasts. No model accurately prognosticated the magnitude nor rate of the intensification. The EMXI—an output from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts—saw the largest average error with 98.5 mph (158.5 km/h) at 48 hours.[2]

Peak strength

During the overnight hours of October 22–23, Patricia turned northwest and decelerated slightly as it reached the western edge of the mid-level ridge.

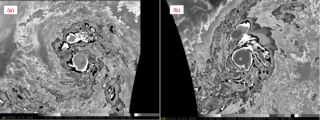

Based on continued improvement of the hurricane's satellite appearance, Patricia is assessed to have achieved its peak intensity around 12:00 UTC on October 23; the storm was situated about 150 mi (240 km) southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico. Maximum winds are estimated at 215 mph (345 km/h) alongside a pressure of 872 mbar (hPa; 25.75 inHg), making Patricia the second-most intense tropical cyclone ever observed. It is possible that Patricia surpassed the all-time record of 870 mbar (hPa; 25.69 inHg) set by Typhoon Tip in 1979 given the rate of deepening observed during the early morning mission.[2] The violent, compact core of Patricia was roughly 25 mi (40 km) wide with the radius of maximum winds extending only 7 mi (11 km).[2][19]

Little change in strength took place for the next six hours; a

Landfall and dissipation

Late on October 23, radar imagery depicted the formation of a secondary outer eyewall, indicative of an eyewall replacement cycle. By 20:30 UTC, the final pass by reconnaissance, the hurricane's flight-level winds fell by 60 mph (97 km/h) and its central pressure rose at 8 mbar (hPa; 0.236 inHg) per hour. Coinciding with the eyewall replacement cycle was an increase in southwesterly wind shear, a factor that further accelerated Patricia's degradation.[2] The hurricane's eye soon became cloud-filled and rapid weakening ensued at an unprecedented pace.[2][21]

At 23:00 UTC, the cyclone made landfall at Cuixmala in the municipality of La Huerta, Jalisco—about 55 mi (89 km) west-northwest of Manzanillo—with estimated winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and an estimated pressure of 932 mbar (hPa; 27.52 inHg).[2][22][nb 5] This made Patricia the strongest hurricane recorded at the time to strike Mexico's Pacific coast, exceeding an unnamed storm in 1959 and Madeline in 1976 (the latter of which has not been reanalyzed); Patricia's record was later surpassed by Hurricane Otis in 2023.[23][24] Although Patricia was operationally thought to have made landfall as a Category 5 hurricane with winds of 165 mph (266 km/h) and a pressure of 920 mbar (hPa; 27.17 inHg),[25] reanalysis of available data suggested that the hurricane weakened more rapidly than originally thought:[2] an automated station in Cuixmala measured a pressure of 934.2 mbar (934.2 hPa; 27.59 inHg),[2] while Josh Morgerman in Emiliano Zapata, just inside the eye of Patricia, measured a pressure of 937.8 mbar (hPa; 27.69 inHg). His observations also indicated a pressure gradient of 11 mbar (hPa; 0.325 inHg) per nautical mile.[19]

Patricia's winds at landfall are relatively uncertain, and the 150 mph (240 km/h) value is based upon the Knaff–Zehr–Courtney pressure–wind relationship and an extrapolation of a 54 mbar (hPa; 1.59 inHg) filling using the Dvorak technique. An additional equation stemming from work by Willoughby (1993) yielded a landfall intensity of 147 mph (237 km/h). A NOAA automated weather station at the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve, at an elevation of 280 ft (85 m), recorded sustained winds of 185 mph (298 km/h) and a maximum gust of 211 mph (340 km/h).[2] Further raw data from this station indicated unrealistically high sustained winds of 266 mph (428 km/h) and a maximum gust of 1,138 mph (1,831 km/h).[2][26] Based on the station's distance from Patricia's eye, outside the radius of maximum winds, the observations from this station are considered unreliable. The highest reliably measured winds of 98 mph (158 km/h) occurred in Pista between 22:30 and 23:00 UTC on October 23 before the anemometer failed.[2]

Even faster weakening ensued through October 24 as the hurricane traversed the Sierra Madre mountains;[2] its eye disappeared from satellite imagery within hours of moving ashore.[27] The system weakened below hurricane strength by 03:00 UTC as it passed west of Guadalajara.[2] Patricia accelerated inland between a trough over Northwestern Mexico and the ridge over the Gulf of Mexico. Convection dramatically decreased in organization and the low- and mid- to upper-level circulation centers of the cyclone soon decoupled.[28][29] The system degraded into a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC as little organized convection remained, and the storm dissipated shortly thereafter over central Mexico.[2] Unimpeded by the mountains of Mexico, the mid- to upper-level circulation of Patricia, accompanied by considerable moisture, continued northeast and interacted with a cold front over the western Gulf of Mexico. The new system produced flooding rains across large areas of Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas.[30][31][32]

| Hurricane | Season | Wind speed | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Otis | 2023 | 160 mph (260 km/h) | [33] |

| Patricia | 2015 | 150 mph (240 km/h) | [34] |

| Madeline | 1976 | 145 mph (230 km/h) | [35] |

| Iniki | 1992 | [36] | |

| Twelve | 1957 | 140 mph (220 km/h) | [37] |

| "Mexico" | 1959 | [37] | |

| Kenna | 2002 | [38] | |

| Lidia | 2023 | [39] |

Records

With maximum sustained winds of 215 mph (345 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 872 mbar (hPa; 25.75 inHg), Hurricane Patricia is the second-most intense tropical cyclone ever observed, just shy of Typhoon Tip in 1979 which had a minimum pressure of 870 mbar (hPa; 25.69 inHg). It is also the strongest tropical cyclone ever recorded in the Western Hemisphere.[2] It exceeded the previous sustained wind record of 190 mph (305 km/h) set by Hurricane Allen in 1980 and the pressure record of 882 mbar (hPa; 26.05 inHg) set by Hurricane Wilma in 2005, both in the Atlantic basin.[40] In the Eastern Pacific basin, north of the equator and east of the International Date Line, the previous basin record-holder was Hurricane Linda in 1997 with winds of 185 mph (300 km/h) and a pressure of 902 mbar (hPa; 26.64 inHg).[23] Reconnaissance also found a pressure gradient of 24 mbar (hPa; 0.709 inHg) per nautical mile early on October 23, among the steepest gradients ever observed in a tropical cyclone.[2]

On a global scale, Patricia's one-minute maximum sustained winds rank as the highest ever reliably observed or estimated globally in a tropical cyclone, surpassing

The magnitude of Patricia's rapid intensification is among the fastest ever observed. In a 24-hour period, 06:00–06:00 UTC October 22–23, its maximum sustained winds increased from 85 mph (140 km/h) to 205 mph (335 km/h). This represents a record increase of 120 mph (195 km/h). During the same period, Patricia's central pressure fell by 95 mbar (hPa; 2.81 inHg).

See also

Other record-strength tropical cyclones:

- El Niñoevent

- Typhoon Megi in 2010 – Research reconnaissance observed similarly intense sustained winds

- Typhoon Goni in 2020 – Strongest landfalling tropical cyclone by 1-minute sustained winds

- Typhoon Nancy in 1961 – Tied with Patricia for the highest winds observed in a tropical cyclone, considered unreliable

- Typhoon Tip in 1979 – Most intense tropical cyclone recorded in terms of pressure

- Hurricane Wilma in 2005 – Previous record low central pressure in the Western Hemisphere, still record low for the Atlantic

- Hurricane Allen in 1980 – Previous record high sustained winds in the Western Hemisphere, still record high for the Atlantic

- Typhoon Forrest in 1983 – Record-fastest intensification of any tropical cyclone; underwent a 100 mbar (hPa; 2.953 inHg) pressure drop in just under 24 hours

Notes

- ^ These sea surface temperatures were at record levels for mid-October in the region and were largely undisturbed since Hurricane Carlos in June.[2]

- ^ Post-storm reanalysis concluded that Patricia's peak intensity occurred between the reconnaissance flights, and thus the actual minimum pressure at peak intensity was estimated at 872 mbar (hPa; 25.75 inHg). However, this measured value of 879 mbar (hPa; 25.96 inHg)—extrapolated from a direct observation of 883 mbar (hPa; 26.07 inHg) with surface winds of 52 mph (84 km/h)—remains the lowest directly-measured central pressure in a Western Hemisphere tropical cyclone.[2]

- ^ The maximum SFMR winds for the 06:00 UTC mission were operationally withheld for quality assurance and later determined to be accurate.[2]

- ^ This pressure value was extrapolated from an observation of 885 mbar (hPa; 26.13 inHg) with surface winds of 66 mph (106 km/h).[2]

- ^ The landfall pressure is based upon several observations in the hurricane's eye and has an error margin of ± 2–3 mbar (hPa; 0.06–0.09 inHg).[2]

References

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization retires storm names Erika, Joaquin and Patricia" (Press release). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 25, 2016. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as Todd B. Kimberlain; Eric S. Blake & John P. Cangialosi (February 1, 2016). Hurricane Patricia (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ Bibcode:2016AGUFM.A54F..07B. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2016.)

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help - ^ Philippe P. Papin; Kyle S. Griffin; Lance F. Bosart & Ryan D. Torn (2013). "A Climatology of Central American Gyres" (PDF). University of Albany. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ^ Todd B. Kimberlain (October 17, 2015). Tropical Weather Outlook (.TXT) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- (PDF) from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ Todd B. Kimberlain (October 18, 2015). Tropical Weather Outlook (.TXT) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ Todd B. Kimberlain (October 19, 2015). Tropical Weather Outlook (.TXT) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on November 23, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ Dave Roberts (October 19, 2015). Tropical Weather Outlook (.TXT) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (October 21, 2015). Tropical Storm Patricia Discussion Number 4 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ Jack L. Beven (October 21, 2015). Tropical Storm Patricia Discussion Number 5 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Todd B. Kimberlain (October 20, 2015). Tropical Depression Twenty-E Discussion Number 1 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (October 22, 2015). Hurricane Patricia Discussion Number 8 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Stacy R. Stewart (October 22, 2015). Tropical Storm Patricia Discussion Number 7 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- ^ a b Michael J. Brennan (October 22, 2015). Hurricane Patricia Discussion Number 11 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (October 23, 2015). Hurricane Patricia Discussion Number 12 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (October 23, 2015). Hurricane Patricia Intermediate Advisory Number 11a (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ^ Scott Stripling (October 22, 2015). Tropical Weather Discussion (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on July 14, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ a b Josh Morgerman (November 2, 2015). iCyclone Chase Report: Hurricane Patricia (PDF) (Report). iCyclone. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Scott Sistek (October 25, 2015). "Watch: 'Most intense turbulence' as NOAA flies through Hurricane Patricia". KOMO-TV. American Broadcasting Company. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ Jack L. Beven (October 23, 2015). Hurricane Patricia Discussion Number 16 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ Patricia Tocó Tierra en Costa de Jalisco (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Comisión Nacional de Agua. October 24, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 8, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ a b National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center (April 4, 2023). "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2022". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Josh Morgerman (October 27, 2014). "Great Mexico Hurricane of 1959: Reanalyzing a Monster". iCyclone. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ Eric S. Blake & Stacy R. Stewart (October 23, 2015). "Hurricane Patricia Tropical Cyclone Update". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ "7 Day Observations from Data Collection Platform (DCP) CCXJ1". National Weather Service. October 23, 2015. Archived from the original on October 29, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ Eric S. Blake & Stacy R. Stewart (October 24, 2015). Hurricane Patricia Discussion Number 17 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ John P. Cangialosi & Stacy R. Stewart (October 24, 2015). Hurricane Patricia Discussion Number 18 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ Jack L. Beven (October 24, 2015). Tropical Depression Patricia Discussion Number 19 (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ Jeff Masters & Bob Henson (October 24, 2015). "Patricia's Remnants to Fuel Dangerous Rains in Texas". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ Amanda K. Fanning (October 24, 2015). Storm Summary Number 10 for Southern Plains Heavy Rainfall (Report). College Park, Maryland: Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on June 7, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ Amanda K. Fanning (October 24, 2015). Storm Summary Number 15 for Southern Plains Heavy Rainfall (Report). College Park, Maryland: Weather Prediction Center. Archived from the original on October 26, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- ^ Brown, Daniel; Kelly, Larry (October 25, 2023). Hurricane Otis Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). Miami, Florida. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ Kimberlain, Todd B.; Blake, Eric S.; Cangialosi, John P. (February 1, 2016). Hurricane Patricia (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- . Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ The 1992 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season (PDF) (Report). Honolulu, Hawaii: Central Pacific Hurricane Center. 1993. Retrieved November 24, 2003.

- ^ a b Blake, Eric S; Gibney, Ethan J; Brown, Daniel P; Mainelli, Michelle; Franklin, James L; Kimberlain, Todd B; Hammer, Gregory R (2009). Tropical Cyclones of the Eastern North Pacific Basin, 1949-2006 (PDF). Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ Franklin, James L. (December 26, 2002). Hurricane Kenna (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Bucci, Lisa; Brown, Daniel (October 10, 2023). Hurricane Lidia Intermediate Advisory Number 31A (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ^ "North Atlantic Hurricane Best Tracks (HURDAT2)". Hurricane Research Division. National Hurricane Center. February 17, 2016. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- University of Wisconsin-Madison. n.d. Archivedfrom the original on February 13, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Dennis Mersereau (October 23, 2015). "At 200 MPH, Hurricane Patricia Is Now the Strongest Tropical Cyclone Ever Recorded". The Vane. Gawker Media. Archived from the original on October 23, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ Christopher W. Landsea (April 21, 2010). "Subject: E1) Which is the most intense tropical cyclone on record?". Frequently Asked Questions. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ "5 Things to Know About Hurricane Patricia". Atlanta, Georgia: The Weather Channel. October 23, 2015. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ "World: Maximum Surface Wind Gust (3-Second)". World Meteorological Organization. 2010. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone: Fastest Intensification of Tropical Cyclone". World Meteorological Organization. n.d. Archived from the original on April 20, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2015.