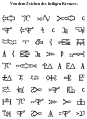

Miꞌkmaw hieroglyphs

| Miꞌkmaw hieroglyphic writing Suckerfish script Gomgwejui'gasit | |

|---|---|

Ave Maria written in Miꞌkmaw hieroglyphic writing. | |

| Script type | |

Time period |

|

Miꞌkmaw hieroglyphic writing or Suckerfish script (

These glyphs, or gomgwejui'gaqan, were derived from a

Classification

Scholars have debated whether the earliest known Miꞌkmaw "hieroglyphs", from the 17th century, qualified fully as a

In 1978, Ives Goddard and William Fitzhugh of the Department of Anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution, contended that the pre-missionary system was purely mnemonic.[citation needed] They said that it could not have been used to write new compositions.[citation needed]

By contrast, in a 1995 book, David L. Schmidt and Murdena Marshall published some of the post-missionary prayers, narratives, and liturgies, as represented by hieroglyphs—pictographic symbols, which the French missionaries had used in the last quarter of the seventeenth century, to teach prayers and hymns.[2] Schmidt and Marshall showed that these hieroglyphics served as a fully functional writing system.[2] They said that it was the oldest writing system for a native language in North America north of Mexico.[2]

Michelle Sylliboy[4] indicates that "(a) French missionary stole our historical narrative with outlandish claims about our written language," and cites her Mikm'aw grandmother (Lillian B. Marshall, 1934-2018) who stated in her "last conversation before she died, to make sure to tell “them” that we’ve always had our language," seemingly asserting that Le Clercq did not invent the script, and it had been in use by the people long before him. However, this does not square with the fact that after Le Clerq's return to France in 1687, the script had to be taught to other groups of Mi'kmaq by other missionaries, indicating it was not a script that the indigenous peoples already knew.[5]

History

Father Le Clercq, a

This adapted writing system proved popular among Miꞌkmaq. They were still using it in the 19th century.[citation needed] Since there is no historical or archaeological evidence of these symbols from before the arrival of this missionary, it is unclear how ancient the use of the pre-missionary mnemonic glyphs was. The relationship of these symbols to Miꞌkmaq petroglyphs, which predated European encounter, is unclear.

The Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site (KNPNHS), petroglyphs of "life-ways of the Mi'kmaw", include written hieroglyphics, human figures, Mi'kmaq houses and lodges, decorations including crosses, sailing vessels, and animals, etched into slate rocks. These are attributed to the Mi'kmaq, who have continuously inhabited the area since prehistoric times.[7]: 1 The petroglyphs date from the late prehistoric period through the nineteenth century.[7]: 32 A Mi'kmaq healer, Jerry Lonecloud, transcribed some of these petroglyphs in 1912, and donated his copies to the provincial museum.[7]: 6 [8]

Examples

-

The beginning of the Lord's Prayer in Míkmaq hieroglyphs. The text reads Nujjinen wásóq – "Our father / in heaven"

-

The full text.

-

Text of the Rite of Confirmation in Míkmaq hieroglyphs. The text reads Koqoey nakla msɨt telikaqumilálaji? – literally 'Why / those / all / after he did that to them?', or "Why are all these different steps necessary?"

-

Page 5 of Buch das gut, enthaltend den Katechismus by Christian Kauder

See also

- Wiigwaasabak – Ojibwe hieroglyphic birchbarks

References

- ISBN 978-0-8108-5113-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55109-069-6.

- ISBN 1-55109-069-4.

- ^ Sylliboy, Michelle (26 June 2022). "Artist's Notes: Nm'ultes is an Active Dialogue I: Reclaiming Komqwejwi'kasikl – by Michelle Sylliboy – Journal18: a journal of eighteenth-century art and culture". Journal18.

- ISBN 1-55109-069-4.

- ^ McCord Museum. Archived from the originalon October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c Cave, Beverley (September 2005). The Petroglyphs of Kejimkujik National Park, Nova Scotia: A Fresh Perspective on their Physical and Cultural Contexts (PDF). Memorial University (Thesis). Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ISBN 0-86492-356-2.

- ^ Johnson, Micheline D. (1974). "Maillard, Pierre". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

Bibliography

- Goddard, Ives; Fitzhugh, William W. (1978). "Barry Fell Reexamined". The Biblical Archaeologist. 41 (3): 85–88. S2CID 166199331.

- Hewson, John (1982). Paddock, Harold (ed.). Micmac Hieroglyphs in Newfoundland. Languages in Newfoundland and Labrador (2nd ed.). St John's, Newfoundland: Memorial University. pp. 188–199.

- Hewson, John (1988). "Introduction to Micmac Hieroglyphics". Cape Breton Magazine (47): 55–61. (text of 1982, plus illustrations of embroidery and some photos)

- Kauder, Christian (1921). Sapeoig Oigatigen tan teli Gômgoetjoigasigel Alasotmaganel, Ginamatineoel ag Getapefiemgeoel; Manuel de Prières, instructions et changs sacrés en Hieroglyphes micmacs; Manual of Prayers, Instructions, Psalms & Hymns in Micmac Ideograms. New edition of Father Kauder's Book published in 1866. Ristigouche, Quebec: The Micmac Messenger.

- Lenhart, John. History relating to Manual of prayers, instructions, psalms and hymns in Micmac Ideograms used by Micmac Indians of Eastern Canada and Newfoundland. Sydney, Nova Scotia: The Nova Scotia Native Communications Society.

- Schmidt, David L.; Balcom, B. A. (Autumn 1993). "The Règlements of 1739: A Note on Micmac Law and Literacy". Acadiensis. XXIII (1): 110–127. ISSN 0044-5851.

- Schmidt, David L.; Marshall, Murdena (1995). Míkmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America's First Indigenous Script. Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 1-55109-069-4.

External links

- Míkmaq Portraits Collection Includes tracings and images of Miꞌkmaw petroglyphs

- Micmac at ChristusRex.org A large collection of scans of prayers in Miꞌkmaw hieroglyphs.

- Écriture sacrée en Nouvelle France: Les hiéroglyphes micmacs et transformation cosmologique (PDF, in French) A discussion of the origins of Miꞌkmaw hieroglyphs and sociocultural change in the 17th century Miꞌkmaw society.