Miami people

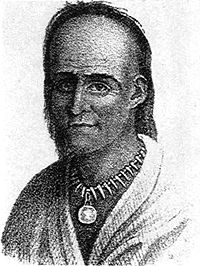

Kee-món-saw, Little Chief, Miami chief, painted by George Catlin, 1830 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,908 (2011)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States |

The Miami (

Name

The name Miami derives from Myaamia (plural Myaamiaki), the tribe's

| Name | Source[3] | Name | Source[3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maiama | Maumee | later French | |

| Meames | Memilounique | French | |

| Metouseceprinioueks | Myamicks | ||

| Nation de la Grue | French | ||

| Omameeg | Omaumeg | Chippewa | |

| Oumami (or Oumiami) | Oumamik | 1st French | |

| Piankashaw | Quikties | ||

| Tawatawas | Titwa | ||

| Tuihtuihronoons | Twechtweys | ||

| Twightwees | Delaware | Wea | band |

History

Prehistory

| 1654 | Fox River, southwest of Lake Winnebago |

|---|---|

| 1670–95 | Wisconsin River, below the Portage to the Fox River |

| 1673 | Niles, Michigan |

| 1679–81 | Fort Miamis, at St. Joseph, Michigan |

| 1680 | Fort Chicago |

| 1682–2014 | Fort St. Louis, at Starved Rock, Illinois |

| 1687 | Calumet River, at Blue Island, Illinois |

| c. 1691 | Wabash River, at the mouth of the Tippecanoe River |

| [4][5] | |

Early Miami people are considered to belong to the Fischer Tradition of

Written history of the Miami traces back to missionaries and explorers who encountered them in what is now

Historic locations[3]

| Year | Location |

|---|---|

| 1658 | Northeast of Lake Winnebago, Wisconsin (Fr) |

| 1667 | Mississippi Valley of Wisconsin |

| 1670 | Head of the Fox River, Wisconsin; Chicago village |

| 1673 | St. Joseph River Village, Michigan (River of the Miamis) (Fr), |

| Kalamazoo River Village, Michigan | |

| 1703 | Detroit village, Michigan |

| 1720–63 | Miami River locations, Ohio |

| Scioto River village (near Columbus), Ohio | |

| 1764 | Wabash River villages, Indiana |

| 1831 | Indian Territory (Oklahoma) |

European contact

When

Around the beginning of the 18th century, with support from French traders coming down from what is now Canada who supplied them with firearms and wanted to trade with them for furs, the Miami pushed back into their historical territory and resettled it. At this time, the major bands of the Miami were:

- Atchakangouen, Atchatchakangouen, Atchakangouen, Greater Miami or Crane Band (named after their leading clan, largest Miami band – their main village was Saint Joseph (Kociihsa Siipiiwi) (″Bean River″), Saint Marys (Nameewa Siipiiwi/Mameewa Siipiiwi) (″River of the Atlantic sturgeon″) and Maumee River (Taawaawa Siipiiwi) (″River of the Odawa″) on the western edge of the Great Black Swampin present-day Indiana – this place was although called saakiiweeki taawaawa siipiiwi (lit. ″the confluence of the Maumee River″); Kekionga / Kiihkayonki was although the capital of the Miami confederacy)

- Kilatika, Kilatak, Kiratika called by the French, later known by the English as Eel River (Kineepikwameekwa Siipiiwi) ("Snake-Fish-River") (near Columbia City, Indiana) down to its mouth at the Wabash River (Waapaahšiki Siipiiwi) (″Shining White River/Bright Shiny River″) (near Logansport, Indiana) in northern Indiana; the Kilatika Band of the French years had their main village at the confluence of the Kankakee River and Des Plaines Rivers to form the Illinois River about 16 km southwest of today's Joliet, Illinois)

- Mengakonkia or Mengkonkia, Michikinikwa("Little Turtle")' people

- Pepikokia, Pepicokea, later known as Tepicon Band or Tippecanoe Band; autonym: Kiteepihkwana (″People of the Place of the buffalo fish″), their main village Kithtippecanuck / Kiteepihkwana (″Place of the buffalo fish″) moved its location various times from the headwaters of the Tippecanoe River (Kiteepihkwana siipiiwi) (″River of the buffalo fish″) (east of Old Tip Town, Indiana) to its mouth into the Wabash River (Waapaahšiki Siipiiwi) (near Lafayette, Indiana) – sometimes although known as Nation de la Gruë or Miamis of Meramec River, possibly the name of a Miami-Illinois band named Myaarameekwa (″Ugly Fish, i.e. Catfish Band″) that lived along the Meramec River (″River of the ugly fish″)[9][10]

- Vermilion River (Peeyankihšiaki Siipiiwi) (″River of the Peeyankihšiaki/Piankashaw″)[11] and Wabash Rivers (Waapaahšiki Siipiiwi) in Illinois and later along the Great Miami River (Ahsenisiipi) (″Rocky River″) in western Ohio, their first main village Peeyankihšionki (″Place of the Peeyankihšiaki/Piankashaw″) was at the confluence of Vermilion River and the Wabash River (near Cayuga, Indiana) – one minor settlement was at the confluence of the main tributaries of the Vermilion River (near Danville, Illinois), the second important settlement was named Aciipihkahkionki / Chippekawkay / Chippecoke (″Place of the edible Root″) and was situated at the mouth of the Embarras River in the Wabash River (near Vincennes, Indiana), in the 18th century a third settlement outside the historic Wabash River Valley named Pinkwaawilenionki / Pickawillany (″Ash Place″) was erected along the Great Miami River (which developed into Piqua, Ohio)[b][12]

- Ouiatanon" was both referred to a group of extinct five Wea settlements or to their historic tribal lands along the Middle Wabash Valley between the Eel River to the north and the Vermilion River to the south, the ″real″Quiatanon at the mouth of the Wea Creek into the Wabash River was their main village[c][13][14]

In 1696, the

By the 18th century, the Miami had for the most part returned to their homeland in present-day Indiana and Ohio. The eventual victory of the British in the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War) led to an increased British presence in traditional Miami areas.

Shifting alliances and the gradual encroachment of European-American settlement led to some Miami bands, including the Piankeshaw, and Wea, effectively merging into what was sometimes called the Miami Confederacy. Native Americans created larger tribal confederacies led by Chief Little Turtle; their alliances were for waging war against Europeans and to fight advancing white settlement, and the broader Miami itself became a subset of the so-called Western Confederacy during the Northwest Indian War.

The U.S. government later included the Miami with the

Locations

- 1718–94 Kekionga, Portage of the Maumee and Wabash rivers, Fort Wayne, Indiana

- 1720–49 Portage of the St. Joseph and Kankakeerivers

- unknown – 1733 Tepicon of the Wabash, Fort Ouiatenon, Lafayette, Indiana

- 1733–51 Tepicon of the Tippecanoe, headwaters of the Tippecanoe River near Warsaw

- 1748–52 Pickawillany, Piqua on the Great Miami River in Ohio

- 1752 Headwaters of the Eel River, southwest of Columbia City, Indiana

- 1752 Le Gris, Maumee River (Miami River), east of Fort Wayne

- 1763 Captured British at Fort Miami (1760–63) as a part of the Pontiac's Rebellion

- 1774 Warriors participated in Lord Dunmore's Warin Ohio

- 1778 Kenapacomaqua, Wabash at the mouth of the Eel River, Logansport, Indiana

- 1780 October – St. Louis) headed a raid of Detroit. Stopped and raided Kekionga. La Balme withdrew to the west, where Little Turtle destroyed the raiders, killing one third of them, on November 5.

United States and Tribal Divide

The Miami had mixed relations with the United States. Some villages of the Piankeshaw openly supported the American rebel colonists during the American Revolution, while the villages around Ouiatenon were openly hostile. The Miami of Kekionga remained allies of the British, but were not openly hostile to the United States (except when attacked by Augustin de La Balme in 1780).

In the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolutionary War, Britain transferred its claim of sovereignty over the Northwest Territory – modern-day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin – to the new United States. White pioneers pushed into the Ohio Valley, leading to disputes over whether they had a legal right to carve out homesteads and settlements on land the tribes considered unceded territory. The Miami invited tribes displaced by white settlers, the Delaware (Lenape) and Shawnee to resettle at Kekionga, forming the nucleus of the pan-tribal Western Confederacy. War parties attacked white settlers, seeking to drive them out, and whites – including Kentucky militia members – carried out sometimes indiscriminate reprisal attacks on Native American villages. The resulting conflict became known as the Northwest Indian War.

Seeking to bring an end to the rising violence by forcing the tribes to sign treaties ceding land for white settlement, the George Washington administration ordered an attack on Kekionga in 1790;

Those Miami who still resented the United States gathered around Ouiatenon and Prophetstown, where Shawnee Chief Tecumseh led a coalition of Native American nations. Territorial governor William Henry Harrison and his forces destroyed Prophetstown in 1811, and in the War of 1812 – which included a tribal siege of Fort Wayne – attacked Miami villages throughout the Indiana Territory.

Although Wayne had promised in the Treaty of Greenville negotiations that the remaining unceded territory would remain tribal land – the origin of the name "Indiana" – forever, that is not what happened. Wayne would die a year later. White traders who came to Fort Wayne were used by the government to deliver the annual treaty payments to the Miami and other tribes. The traders also sold them alcohol and manufactured goods. Between annuity days, the traders sold them such things on credit, and the tribes repeatedly ran up more debts than the existing payments could cover. Harrison and his successors pursued a policy of leveraging these debts to induce tribal leaders to sign new treaties ceding large swaths of collectively-held reservation land and then to agree to the tribe's removal. As incentives to induce tribal leaders to sign such treaties, the government gave them individual deeds and other personal perks, such as building one chief a mansion. In 1846, the government forced the tribe's rank-and-file to leave, but several major families who had acquired private property to live on through this practice were exempted and permitted to stay in Indiana, creating a bitter schism.[16]

Those who affiliated with the tribe were moved to first to Kansas, then to Oklahoma, where they were given individual allotments of land rather than a reservation as part of efforts to make them assimilate into the American culture of private property and yeoman farming.[16] The U.S. government has recognized what is now the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma as the official tribal government since 1846.

In the 20th century, the Indiana-based Miami unsuccessfully sought separate federal recognition. Although they had been recognized by the U.S. in an 1854 treaty, that recognition was stripped in 1897. In 1980, the Indiana legislature recognized the Eastern Miami as a matter of state law and voted to support federal recognition,[5]: 291 but in 1993, a federal judge ruled that the statute of limitations on appealing their status had expired.[5]: 293 In 1996, the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma changed its constitution to permit any descendant of people on certain historical roles to join, and since then hundreds of Indiana-based Miami have become members. Today the Oklahoma-based Miami tribe has about 5,600 enrolled members.[16] However many other Indiana-based Miami still consider themselves a separate group that has been unfairly denied separate federal recognition. The Miami Nation of Indiana does not have federal tribal recognition. Senate Bill No. 311 was introduced in the Indiana General Assembly in 2011 to formally grant state recognition to the tribe, giving it sole authority to determine its tribal membership,[20][21] but the bill did not advance to a vote.

Locations

- 1785 – Delaware villages located near Kekionga (refugees from American settlements)

- 1790 – Pickawillany Miami join Kekionga (refugees from American settlements)

- 1790 Gen. Josiah Harmar is ordered to attack and destroy Kekionga. On October 17, Harmar's forces burn the evacuated villages but are then defeated by Little Turtle's warriors.

- 1790-1791 – Rather than rebuilding Kekionga, tribes resettle further down the Maumee River, including at what is now Defiance, Ohio

- 1791 Gen. Arthur St. Clair attempts to attack Kekionga again and build a fort there, but before he can get there the Western Confederacy attacks his camp and destroys his army near the future Fort Recovery.

- Kentucky Militia destroy Eel River villages.

- 1793 December – General Anthony Wayne launches third invasion and builds Fort Recovery on the site of St. Clair's Defeat.

- 1794 June – Fort Recovery repulses attack by Western Confederacy

- 1794 August – Battle of Fallen Timbers near modern-day Toledo; Wayne's forces defeat Western Confederacy

- 1794 September – Wayne's forces march up the Maumee River, burning tribal villages and fields (where tribes resettled after Harmar destroyed Kekionga) for dozens of miles, before reaching the abandoned ruins of Kekionga at its headwaters and building Fort Wayne

- 1795 – Tribal leaders sign the Treaty of Greenville, ceding most of what is now Ohio as well as the area around Fort Wayne that includes its historic capital of Kekionga and the Maumee-Wabash land portage

- 1809 – Gov. William Henry Harrison orders destruction of all villages within two days' march of Fort Wayne. Villages near Columbia City and Huntington destroyed.

- 1812 17 December – Lt. Col. John B. Campbell ordered to destroy the Mississinewa villages. Campbell destroys villages and kills 8 Indians and 76 were taken prisoner, including 34 women and children.[22]

- 1812 18 December, at Silver Heel's village, a sizeable Native American force counterattacked. The American Indians were outnumbered, but fought fiercely to rescue the captured villagers being held by Campbell, A joint cavalry charge led by Major James McDowell and Captains Trotter and Johnston finally broke the attack.[23] an estimated 30 Indians were killed; Americans repulsed and return to Greenville.[22]

- 1813 July – U.S. Army returns and burns deserted town and crops.

- 1817 Maumee Treaty – lose Ft. Wayne area (1400 Miami counted)

- 1818 Treaty of St. Mary's (New PurchaseTreaty) – lose south of the Wabash – Big Miami Reservation created. Grants on the Mississinewa and Wabash given to Josetta Beaubien, Anotoine Bondie, Peter Labadie, Francois Lafontaine, Peter Langlois, Joseph Richardville, and Antoine Rivarre. Miami National Reserve (875,000) created.

- 1818 Eel River Miami settle at Thorntown, northeast of Lebanon).

- 1825 1073 Miami, including the Eel River Miami

- 1826 Mississinewa Treaty – Tribe cedes most of its remaining reservation land in northeastern Indiana, which the government wanted to create a right of way for a canal linking Lake Erie to the Wabash River. Miami chief Jean Baptiste de Richardville receives deed to a large personal property and funds to build a mansion on it for signing. Eel River Miami leave Thorntown, northeast of Lebanon, for Logansport area.

- 1834 Western part of the Big Reservation sold (208,000 acres (840 km2))

- 1838 Potawatomi removed from Indiana. No other Indian tribes in the state. Treaty of 1838 made 43 grants and sold the western portion of the Big Reserve. Richardville exempted from any future removal treaties. Richardsville, Godfroy, Metocina received grants, plus family reserves for Ozahshiquah, Maconzeqyuah (Wife of Benjamin), Osandian, Tahconong, and Wapapincha.

- 1840 Remainder of the Big Reservation (500,000 acres (2,000 km2)) sold for lands in Kansas. Godfroy descendants and Meshingomesia (s/o Metocina), sister, brothers and their families exempted from the removal.

- 1846 – October 1, removal was supposed to begin. It began October 6 by canal boat. By ship to Kansas Landing Kansas City and 50 miles (80 km) overland to the reservation. Reached by 9 November.

- 1847 Godfroy Reserve, between the Wabash and Mississinewa

- Wife of Benjamin Reserve, east edge of Godfroy

- Osandian Reserve, on the Mississinewa, southeast boundary of Godfroy

- Wapapincha Reserve, south of Mississinewa at Godfroy/Osandian juncture

- Tahkonong Reserve, southeast of Wapapincha south of Mississinewa

- Ozahshinquah Reserve, on the Mississinewa River, southeast of Peoria

- Meshingomesa Reserve, north side of Mississinewa from Somerset to Jalapa (northwest Grant County)

- 1872 Most reserves were partially sold to non-Indians.

- 1922 All reserves were sold for debt or taxes for the Miamis.

Places named for the Miami

A number of places have been named for the Miami nation. However,

Towns and cities

Townships

|

CountiesFortsBodies of water and geographical locations

InstitutionsSports teams

|

Notable Miami people

- Memeskia (Old Briton) (c. 1695–1752), Miami chief

- Francis Godfroy (Palawonza) (1788–1840), Miami Chief

- Tetinchoua, a powerful 17th-century Miami chief

- Little Turtle (Mishikinakwa) (c. 1747–1812), 18th-century war chief

- Pacanne (c. 1737–1816), 18th-century chief

- Francis La Fontaine (1810–1847), last principal chief of the united Miami tribe

- Jean Baptiste de Richardville(Peshewa) (c. 1761–1841), 19th-century chief

- Frances Slocum (Maconaquah) (1773–1847), adopted member of the Miami tribe

- William Wells (Apekonit), adopted member of the Miami tribe

- Daryl Baldwin (Kinwalaniihsia), recognized in 2016 with an award from the MacArthur Foundation; founding director of the Myaamia Center nationally and internationally recognized for its research, planning, and implementation of community language and cultural revitalization efforts at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio[26][27]

Notes

- ^ West Fork of the White River was known to the native Miami-Illinois peoples as Wapahani, meaning ″white sands″ or Waapi-nipi Siipiiwi, meaning ″white lake river″.

- ^ Both the Piankashaw and the Wea are known in historic sources as Newcalenous because of their close relationship.

- Ou" representing the sound of "W".

References

- ^ 2011 Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory. Archived 2012-04-24 at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. 2011: 21. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ Costa, David J. (2000). "Miami-Illinois Tribe Names". In Nichols, John (ed.). Papers of the Thirty-first Algonquian Conference. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba. pp. 30–53.

- ^ ISBN 978-0517172476.

- ^ ISBN 978-0806120560.

- ^ ISBN 978-0871951328.

- ISBN 978-0-252-06878-2.

- ^ Carter, Life and Times, 62–63.

- ^ Libby, Dr. Dorothy. (1996). "An Anthropological Report on the Piankashaw Indians". Dockett 99 (a part of Consolidated Docket No. 315)]: Glenn Black Laboratory of Archaeology and The Trustees of Indiana University. Archived from the original on 2008-03-15. Retrieved 2020-04-09.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ http://www.meramecrivermonitor.com/MeramecThenandNow-Revised.pdf Archived 2011-05-16 at the Wayback Machine Revised, 2003, Updates on River and Place Names Origins, Plus Meramec River Source

- ^ "Meramec River Name Origin – Ozark Outdoors Riverfront Resort". ozarkoutdoors.net. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Torp, K. "piankeshaw Indian Village of Vermilion County, IL". genealogytrails.com. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ISBN 0-9617367-3-9.

- ^ "Walking Myaamionki: Quelle für Siedlungs-, Flüsse, Orts- sowie Eigennamen der einzelnen Bands". myaamiahistory.wordpress.com. 16 December 2010.

- ISBN 0-8061-3197-7.

- ^ "Vincennes, Sieur de (Jean Baptiste Bissot". The Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 28. Danbury, Connecticut: Grolier. 1990. p. 130.

- ^ a b c d e Savage, Charlie (2020-07-31). "When the Culture Wars Hit Fort Wayne". Politico. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- ^ "Little Turtle (1752 – July 1812)". The Supreme Court of Ohio & The Ohio Judicial System. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ Sword 2003, p. 159.

- ISBN 978-0-253-34886-9.

- ^ Glenn and Rafert, p. 111.

- ^ "Introduced Version, Senate Bill 0342". Indiana General Assembly. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013. and "Digest of Introduced Bill 0342". Indiana General Assembly. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ a b Gilpin, p. 154

- ^ Allison, 224

- ^ Alemany, Ed (2019-06-30). "Miami ∙ Origins and Name Meaning – Neighborhoods". edalemany.com. Retrieved 2022-10-18.

- ^ a b Drury, Augustus Waldo (1909). History of the City of Dayton and Montgomery County, Ohio, Vol. 1. S. J. Clarke Publishing Company. p. 57.

- ^ "Daryl Baldwin". www.miamioh.edu.

- ^ "Daryl Baldwin - MacArthur Foundation". www.macfound.org.

- Magnin, Frédéric (2005). Mottin de la Balme, cavalier des deux mondes et de la liberté (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-7475-9080-1.

External links

- Miami Indian Collection (MSS 004)

- Guide to Native American Resources

- . Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . . 1914.