Microcomputer

A microcomputer is a small, relatively inexpensive

The abbreviation "micro" was common during the 1970s and 1980s,[4] but has since fallen out of common usage.

Origins

The term microcomputer came into popular use after the introduction of the minicomputer, although Isaac Asimov used the term in his short story "The Dying Night" as early as 1956 (published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in July that year).[5] Most notably, the microcomputer replaced the many separate components that made up the minicomputer's CPU with one integrated microprocessor chip.

In 1973, the French

In the US the earliest models such as the Altair 8800 were often sold as kits to be assembled by the user, and came with as little as 256 bytes of RAM, and no input/output devices other than indicator lights and switches, useful as a proof of concept to demonstrate what such a simple device could do.[6] As microprocessors and semiconductor memory became less expensive, microcomputers grew cheaper and easier to use.

- Increasingly inexpensive logic chips such as the keyboardinput, instead of simply a row of switches to toggle bits one at a time.

- Use of audio cassettes for inexpensive data storagereplaced manual re-entry of a program every time the device was powered on.

- Large cheap arrays of silicon turnkey systemthat does not require a computer expert to understand or to use the device.

- teletypewriterthat was previously common as an interface to minicomputers and mainframes.

All these improvements in cost and usability resulted in an explosion in their popularity during the late 1970s and early 1980s. A large number of computer makers packaged microcomputers for use in small business applications. By 1979, many companies such as

operating system. The increasing availability and power of , may all be considered examples of microcomputers according to the definition given above.Colloquial use of the term

By the early 2000s, everyday use of the expression "microcomputer" (and in particular "micro") declined significantly from its peak in the mid-1980s.-based microcomputers.

In colloquial usage, "microcomputer" has been largely supplanted by the term "

Description

Monitors, keyboards and other devices for input and output may be integrated or separate. Computer memory in the form of

A microcomputer comes equipped with at least one type of data storage, usually

History

TTL precursors

Although they did not contain any microprocessors, but were built around

The

Another early system, the Kenbak-1, was released in 1971. Like the Datapoint 2200, it used small-scale integrated transistor–transistor logic instead of a microprocessor. It was marketed as an educational and hobbyist tool, but it was not a commercial success; production ceased shortly after introduction.[14]

Early microcomputers

In late 1972, a French team headed by François Gernelle within a small company, Réalisations & Etudes Electroniques (R2E), developed and patented a computer based on a microprocessor – the Intel 8008 8-bit microprocessor. This Micral-N was marketed in early 1973 as a "Micro-ordinateur" or microcomputer, mainly for scientific and process-control applications. About a hundred Micral-N were installed in the next two years, followed by a new version based on the Intel 8080. Meanwhile, another French team developed the Alvan, a small computer for office automation which found clients in banks and other sectors. The first version was based on LSI chips with an Intel 8008 as peripheral controller (keyboard, monitor and printer), before adopting the Zilog Z80 as main processor.

In late 1972, a Sacramento State University team led by Bill Pentz built the Sac State 8008 computer, able to handle thousands of patients' medical records. The Sac State 8008 was designed with the Intel 8008. It had a full set of hardware and software components: a disk operating system included in a series of programmable read-only memory chips (PROMs); 8 Kilobytes of RAM; IBM's Basic Assembly Language (BAL); a hard drive; a color display; a printer output; a 150 bit/s serial interface for connecting to a mainframe; and even the world's first microcomputer front panel.[15][16]

In early 1973, Sord Computer Corporation (now Toshiba Personal Computer System Corporation) completed the SMP80/08, which used the Intel 8008 microprocessor. The SMP80/08, however, did not have a commercial release. After the first general-purpose microprocessor, the Intel 8080, was announced in April 1974, Sord announced the SMP80/x, the first microcomputer to use the 8080, in May 1974.[17]

Virtually all early microcomputers were essentially boxes with lights and switches; one had to read and understand binary numbers and machine language to program and use them (the Datapoint 2200 was a striking exception, bearing a modern design based on a monitor, keyboard, and tape and disk drives). Of the early "box of switches"-type microcomputers, the MITS

The period from about 1971 to 1976 is sometimes called the

Home computers

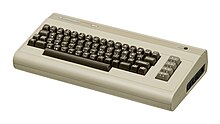

By 1977, the introduction of the second microcomputer generation as

In 1979, the launch of the

See also

- History of computing hardware (1960s–present)

- Lists of microcomputers

- Mainframe computer

- Market share of personal computer vendors

- Minicomputer

- Personal computer

- Keyboard computer

- SFF computer

- Supercomputer

Notes and references

- ^ Kahney, Leander (2003-09-09). "Grandiose Price for a Modest PC". Wired. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ "Microcomputer". dictionary.com.

- S2CID 11184882.

- ISBN 0-86020-637-8), a children's guide to microcomputers.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (July 1956). "The Dying Night". The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

- ISBN 9780262517676.

- ^ "microcomputer". OED Online. December 2013. Oxford University Press. 15 February 2014.

- ^ "personal computer". OED Online. December 2013. Oxford University Press. 15 February 2014

- ^ "The Museum of HP Calculators".

- ^ "Powerful Computing Genie" (PDF). Hewlett Packard. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-03-12. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ "Restoring the Balance Between Analysis and Computation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-06-21. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ "History of the 9100A desktop calculator, 1968". HP virtual museum. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- ^ "MicroprocessorHistory". Computermuseum.li. 1971-11-15. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ "Kenbak-1". The Vintage Computer. Archived from the original on 2011-01-22. Retrieved 2006-08-14.

- ^ "Digibarn Stories: Bill Pentz and (Earliest) History of the Microcomputer (August 2008)". DigiBarn Computer Museum. August–November 2008. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ Terdiman, Daniel (2010-01-08). "Inside the world's long-lost first microcomputer". CNET. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- ^ "SMP80/X series-Computer Museum".

- ^ "16-bit timeline". 19 November 1997.

- ^ "Paper Tape Readers Work With IMP Micros". Computerworld. 23 Oct 1974. p. 28.

- ^ "Upward Compatible Software and Downward Compatible Price". Computerworld. 10 Dec 1975. p. 49.

- ^ Hawkins, William J. (December 1983). "Computer Adventures". Popular Science.