History of Arda

In

Major themes of the history are the

Music of the Ainur

The supreme deity of Tolkien's universe is

Then Ilúvatar created

Ages of Arda

Valian Years

When the

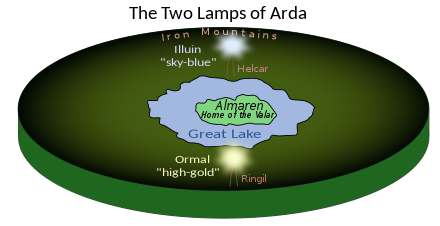

This period, known as the Spring of Arda, was a time when the Valar had ordered the World as they wished and rested upon Almaren, and Melkor lurked beyond the Walls of Night. During this time animals first appeared, and forests started to grow.[T 2] The Spring of Arda was interrupted when Melkor returned to Arda, creating his fortress of Utumno or Udûn beneath the Iron Mountains in the far north. The period ended when Melkor assaulted and destroyed the Lamps of the Valar. Arda was again darkened, and the fall of the great Lamps spoiled the symmetry of Arda's surface. New continents were created:

Years of the Trees

After the destruction of the Two Lamps and the kingdom of

The Years of the Trees were divided into two epochs. The first ten ages, the Days of Bliss, saw peace and prosperity in Valinor. The

After the War of the Powers,

Bitter at the Valar's inactivity, Fëanor and his house left to pursue Melkor, cursing him with the name "Morgoth".

Years of the Sun

The Years of the Sun were the last of the three great time-periods of Arda. They began with the first sunrise in conjunction with the return of the

| Age |

Duration years |

Events | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valian Years | |||||||||

Days before days[T 12] |

3,500 | First War: Marring of Arda | |||||||

Years of the Trees |

1,500 | Yavanna creates the Silmarils

| |||||||

| Years of the Sun | |||||||||

| First Age (cont'd) | 590 | Awakening of Men War of the Jewels War of Wrath: Morgoth's defeat in Beleriand Thangorodrim broken Most of Beleriand drowned | |||||||

| Second Age | 3,441 | removed from Arda | |||||||

| Third Age | 3,021 | War of the Ring: Final defeat of Sauron Destruction of the Elves depart from Middle-earth

| |||||||

| Fourth Age and later | ???? | Tolkien estimated that the Fourth Age began approximately 6,000 years ago and that we would now be in the 6th or 7th Age[T 11] | |||||||

Ages of the Children of Ilúvatar

The First Age of the

First Age

The First Age of the Children of Ilúvatar, also referred to as the Elder Days in The Lord of the Rings, began during the Years of the Trees when the Elves awoke at Cuiviénen, and hence the events mentioned above under Years of the Trees overlap with the beginning of the First Age.[T 13]

Having crossed into Middle-earth, Fëanor was soon lost in an attack on Morgoth's

At the end of the age, all that remained of free Elves and Men in

Second Age

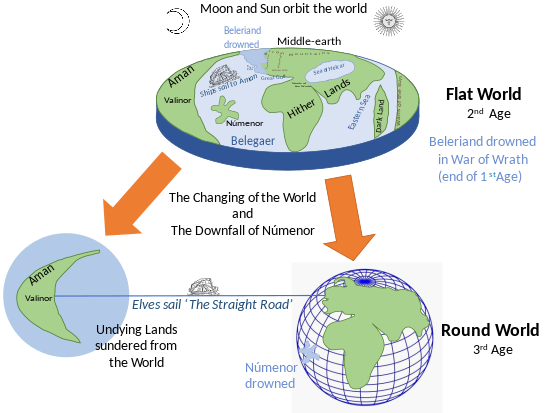

The Second Age is characterized by the establishment and flourishing of

At the start of the Second Age, the Men who had remained faithful were given the island of Númenor, in the middle of the Great Sea, and there they established a powerful kingdom. The

As soon as Sauron put on the One Ring, the Elves realized that they had been betrayed and removed the Three (Sauron eventually obtained the Seven and the Nine. While he was unable to suborn the Dwarf ringbearers, he had more success with the Men who bore the Nine; they became the Nazgûl or Ringwraiths). Sauron then made war on the elves and nearly destroyed them utterly during the Dark Years, but when it seemed defeat was imminent, the Númenóreans joined the battle and completely crushed the forces of Sauron. Sauron never forgot the ruin brought on his armies by the Númenóreans, and made it his goal to destroy them.[T 20]

Towards the end of the age, the Númenóreans became increasingly haughty. Now they sought to dominate other men and to establish kingdoms. Centuries after Tar-Minastir's engagement, when Sauron had largely recovered, Ar-Pharazôn, the last and most powerful of the Kings of

The world was changed into a sphere and the continent of Aman was removed, although a sailing route from Middle-earth to Aman, accessible to the Elves but not to mortals, persisted. Númenor was utterly destroyed, as was the fair body of Sauron; however, his spirit returned to Mordor, where he again took up the One Ring, and gathered his strength once more. Elendil, his sons and the remainder of the Faithful sailed to Middle-earth, where they founded the realms in exile of Gondor and Arnor.[T 20]

Sauron arose again and challenged them. The Elves allied with Men to form the Last Alliance of Elves and Men. For seven years, the Alliance laid siege to

Third Age

The Third Age lasted for 3021 years, beginning with the first downfall of

This age was characterized by the waning of the

The

The so-called Watchful Peace began in

The main events of

Fourth Age

With the end of the Third Age began the Dominion of Men. Elves were no longer involved in Human affairs, and most Elves left for Valinor; those that remain behind "fade" and diminish. A similar fate meets the Dwarves: although

Eldarion, son of Aragorn II Elessar and Arwen Evenstar, became King of the Reunited Kingdom in F.A. 120. Aragorn gave him the tokens of his rule, and then surrendered his life willingly, as his ancestors had done thousands of years before. Arwen left him to rule alone, passing away to the now-empty land of Lórien where she died.[T 28] Upon the death of Aragorn, Legolas departed Middle-earth for Valinor, taking Gimli with him and ending the Fellowship of the Ring in Middle-earth.[T 29]

Tolkien once considered writing a sequel to The Lord of the Rings, called The New Shadow, which would have taken place in Eldarion's reign, and in which Eldarion deals with his people turning to evil practices – in effect, a repetition of the history of Númenor.[T 30] In a 1972 letter concerning this draft, Tolkien mentioned that Eldarion's reign would have lasted for about 100 years after the death of Aragorn.[T 31][d] His realm was to be "great and long-enduring", but the lifespan of the royal house was not to be restored; it would continue to wane until it was like that of ordinary Men.[T 32]

Dagor Dagorath

In a letter, Tolkien wrote that "This legendarium [The Silmarillion] ends with a vision of the end of the world [after all the ages have elapsed], its breaking and remaking, and the recovery of the Silmarilli and the 'light before the Sun' – after a final battle [Dagor Dagorath] which owes, I suppose, more to the Norse vision of Ragnarök than to anything else, though it is not much like it."[T 33] The concept of Dagor Dagorath appears in many of Tolkien's manuscripts that were published by his son Christopher in The History of Middle-earth series, but not in the published Silmarillion, where the eventual fate of Arda is left open-ended in the closing lines of the Quenta Silmarillion.[T 34]

Analysis

Creation and sub-creation

Scholars, noting that Tolkien was a devout

Flieger has observed that the splintering of the created light is a process of decline and fall from a once-perfect state. She identifies a theory of decline that influenced Tolkien, namely Owen Barfield's theory of language in his 1928 book Poetic Diction. The central idea was that there was once a unified set of meanings in an ancient language, and that modern languages are derived from this by fragmentation of meaning.[9] Tolkien took this to imply the separation of peoples, in particular the complicated and repeated sundering of the Elves.[10]

A dark mythology

Scholars including Flieger have noted that if Tolkien intended to create

Greek mythology

Among

"Imagined prehistory"

Arda is summed up by the Tolkien scholar Paul H. Kocher as "our own green and solid Earth at some quite remote epoch in the past."[1] Kocher notes Tolkien's statement in the Prologue, equating Middle-earth with the actual Earth, separated by a long period of time:

Those days, the Third Age of Middle-earth, are now long past, and the shape of all lands has been changed; but the regions in which Hobbits then lived were doubtless the same as those in which they still linger: the North-West of the Old World, east of the Sea. Of their original home the Hobbits in Bilbo’s time preserved no knowledge.[T 38]

In a letter written in 1958, Tolkien states that while the time is invented, the place, planet Earth, is not (italics in original):[T 11]

I have, I suppose, constructed an imaginary time, but kept my feet on my own mother-earth for place. I prefer that to the contemporary mode of seeking remote globes in 'space'... Many reviewers seem to assume that Middle-earth is another planet![T 11]

In the same letter, he places the beginning of the Fourth Age some 6,000 years in the past:[T 11]

I imagine the gap [since

the War of the Ring and the end of the Third Age] to be about 6000 years; that is we are now at the end of the Fifth Age if the Ages were of about the same length as Second Age and Third Age. But they have, I think, quickened; and I imagine we are actually at the end of the Sixth Age, or in the Seventh.[T 11]

The Tolkien scholar

West praises and quotes Kocher on Tolkien's imagined prehistory and the implied process of fading to lead from fantasy to the modern world:[3]

At the end of his epic Tolkien inserts ... some forebodings of [Middle-earth's] future which will make Earth what it is today ... he shows the initial steps in a long process of retreat or disappearance by which all other intelligent species, which will leave man effectually alone on earth... Ents may still be there in our forests, but what forests have we left? The process of extermination is already well under way in the Third Age, and ... Tolkien bitterly deplores its climax today."[20]

The Tolkien scholar

The poet W. H. Auden wrote in The New York Times that "no previous writer has, to my knowledge, created an imaginary world and a feigned history in such detail. By the time the reader has finished the trilogy, including the appendices to this last volume, he knows as much about Tolkien's Middle Earth, its landscape, its fauna and flora, its peoples, their languages, their history, their cultural habits, as, outside his special field, he knows about the actual world."[e][21] The scholar Margaret Hiley comments that Auden's "feigned history" echoes Tolkien's own statement in the foreword to the second edition of Lord of the Rings that he much preferred history, true or feigned, to allegory; and that Middle-earth's history is told in The Silmarillion.[22]

Notes

- Brian Rosebury have noted that it makes more sense to call it the history of Arda, as Middle-earth was just one continent, and the early part of the history largely concerns another continent, Aman (Valinor), not to mention the creation and destruction of the island of Númenor.[2]

- Valar in Arda. The Valian years were measured in Valinor after the first sunrise, but Tolkien provided no dates for events in Aman after that point. Valian years are not used for Beleriand and Middle-earth. In the 1930s and 1940s Tolkien used a figure which fluctuated slightly around ten before settling on 9.582 solar years in each Valian year. However, in the 1950s, Tolkien decided to use a much greater value of 144 solar years per Valian year.[T 3]

- ^ Tolkien wrote "I have written nothing beyond the first few years of the Fourth Age. (Except the beginning of a tale supposed to refer to the end of the reign of Eldarion about 100 years after the death of Aragorn. ...)"[T 31]

- ^ Auden only had The Lord of the Rings to go on in 1956, but he commented that "From the appendices readers will get tantalizing glimpses of the First and Second Ages" and hoped that as the "legend of these" had already been written, readers would not have to wait too long for them.[21]

References

Primary

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, "Ainulindalë"

- ^ a b c d Tolkien 1977, ch. 1 "Of the Beginning of Days"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1993, "Myths Transformed", 9 "Aman"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 5 "Of Eldamar and the Princes of the Eldalië"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 7 "Of the Silmarils and the Unrest of the Noldor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 8 "Of the Darkening of Valinor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 6 "Of Fëanor and the Unchaining of Melkor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 11 "Of the Sun and Moon and the Hiding of Valinor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 13 "Of the Return of the Noldor"

- ^ a b c d e f g h Carpenter 2023, #211 to Rhona Beare, 14 October 1958, last footnote

- ^ Tolkien 1993, "The Annals of Aman", §§ 5-10 "Of the Beginning of Time and its Reckoning"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 17 "Of the Coming of Men into the West"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 18 "Of the Ruin of Beleriand and the Fall of Fingolfin"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 20 "Of the Fifth Battle: Nirnaeth Arnoediad"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, ch. 22 "Of the Ruin of Doriath"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 23 "Of Tuor and the Fall of Gondolin"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, ch. 24 Of the Voyage of Earendil and the War of Wrath

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tolkien 1955, Appendix B: The Tale of Years. "The Second Age"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix D: "Calendars"

- ^ Tolkien 1980, part 2: "The Second Age"

- Akallabêth"

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tolkien 1955, Appendix B: The Tale of Years, "The Third Age"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix A part I(iv), p. 328

- ^ Tolkien 1980, part 3 ch. 2(i) pp. 288–289

- ^ Tolkien 1996, "The Making of Appendix A", '(IV) Durin's Folk', p. 278.

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix A: The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix B: "Later events concerning the members of the Fellowship of the Ring"

- ^ Tolkien 1996, "The New Shadow"

- ^ a b Carpenter 2023, #338 to Fr. Douglas Carter, 6 June 1972

- ^ Tolkien 1996, "The Heirs of Elendil"

- ^ a b c Carpenter 2023, #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

- ^ Tolkien 1986, ch. 3: "Quenta Noldorinwa"

- ^ Tolkien 2001, pp. 85–90

- ^ a b Carpenter 2023, #154 to Naomi Mitchison, September 1954

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #227 to Mrs Drijver, January 1961

- ^ Tolkien 1954a "Prologue"

Secondary

- ^ a b c d Kocher 1974, pp. 8–11.

- ^ Rosebury 2003, pp. 89–133.

- ^ a b c d e West 2006, pp. 67–100

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 324–328.

- ^ Rosebury 1992, p. 97.

- ^ a b Flieger 1983, pp. 44–49.

- ^ Flieger 1983, pp. 6–61, 89–90, 144-145 and passim.

- ^ Chance 1980, p. 133.

- ^ Flieger 1983, pp. 35–41.

- ^ Flieger 1983, pp. 65–87.

- ^ Chance 1980, Title page and passim.

- ^ Flieger 2005, pp. 139–142.

- ^ Garth 2003, Preface, pp. xiii–xviii, 309, and passim.

- ^ Flieger 2001, p. 224.

- ^ Croft 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Purtill 2003, pp. 52, 131.

- ^ Stanton 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Flieger 1983, p. 95.

- ^ a b c d e Lee & Solopova 2005, pp. 256–257

- ^ Kocher 1974, p. 14.

- ^ a b Auden, W. H. (22 January 1956). "Books: At the End of the Quest, Victory". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Hiley 2006.

Sources

- ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- ISBN 978-0-333-29034-7.

- ISBN 978-0-313-32592-2.

- Donovan, Leslie A. (2020) [2014]. "Middle-earth Mythology: An Overview". In ISBN 978-1119656029.

- ISBN 978-0-802-81955-0.

- ISBN 978-0-87338-699-9.

- ISBN 978-0-87338-824-5.

- ISBN 978-0-00711-953-0.

- Hiley, Margaret Barbara (2006). "Aspects of modernism in the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien and Charles Williams". University of Glasgow (PhD Thesis). Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-14-003877-4.

- ISBN 978-1403946713.

- ISBN 978-0-89870-948-3.

- ISBN 978-0-333-53896-8.

- ISBN 978-1-4039-1263-3.

- ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Stanton, Michael (2001). Hobbits, Elves, and Wizards: Exploring the Wonders and Worlds of J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. ISBN 978-1-4039-6025-2.

- OCLC 9552942.

- OCLC 519647821.

- ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.

- ISBN 978-0-395-42501-5.

- ISBN 0-395-68092-1.

- ISBN 978-0-395-82760-4.

- ISBN 978-0-007-10504-5.

- ISBN 978-0-87462-018-4.