Migraine

| Migraine | |

|---|---|

| Usual onset | Around puberty[1] |

| Duration | Recurrent, long term[1] |

| Causes | Environmental and genetic[3] |

| Risk factors | Family history, female[4][5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Subarachnoid hemorrhage, venous thrombosis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, brain tumor, tension headache, sinusitis,[6] cluster headache[7][unreliable medical source?] |

| Prevention | Propranolol, amitriptyline, topiramate[8] |

| Medication | Ibuprofen, paracetamol (acetaminophen), triptans, ergotamines[5][9] |

| Prevalence | ~15%[10] |

Migraine (UK: /ˈmiːɡreɪn/, US: /ˈmaɪ-/)[11][12] is a genetically influenced complex neurological disorder characterized by episodes of moderate-to-severe headache, most often unilateral and generally associated with nausea and light and sound sensitivity.[1] Other characterizing symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, cognitive dysfunction, allodynia, and dizziness. Exacerbation of headache symptoms during physical activity is another distinguishing feature.[13] Up to one-third of migraine sufferers experience aura, a premonitory period of sensory disturbance widely accepted to be caused by cortical spreading depression at the onset of a migraine attack.[13] Although primarily considered to be a headache disorder, migraine is highly heterogenous in its clinical presentation and is better thought of as a spectrum disease rather than a distinct clinical entity.[14] Disease burden can range from episodic discrete attacks, consisting of as little as several lifetime attacks, to chronic disease.[14][15]

Migraine is believed to be caused by a mixture of environmental and genetic factors that influence the excitation and inhibition of

Initial recommended

Globally, approximately 15% of people are affected by migraine.[10] In the Global Burden of Disease Study, conducted in 2010, migraines ranked as the third-most prevalent disorder in the world.[25] It most often starts at puberty and is worst during middle age.[1] As of 2016[update], it is one of the most common causes of disability.[26]

Signs and symptoms

Migraine typically presents with self-limited, recurrent severe headache associated with autonomic symptoms.[5][27] About 15–30% of people living with migraine experience episodes with aura,[9][28] and they also frequently experience episodes without aura.[29] The severity of the pain, duration of the headache, and frequency of attacks are variable.[5] A migraine attack lasting longer than 72 hours is termed status migrainosus.[30] There are four possible phases to a migraine attack, although not all the phases are necessarily experienced:[13]

- The prodrome, which occurs hours or days before the headache

- The aura, which immediately precedes the headache

- The pain phase, also known as headache phase

- The postdrome, the effects experienced following the end of a migraine attack

Migraine is associated with

Prodrome phase

Aura phase

|

|

|

|

Aura is a transient focal neurological phenomenon that occurs before or during the headache.[2] Aura appears gradually over a number of minutes (usually occurring over 5–60 minutes) and generally lasts less than 60 minutes.[37][38] Symptoms can be visual, sensory or motoric in nature, and many people experience more than one.[39] Visual effects occur most frequently: they occur in up to 99% of cases and in more than 50% of cases are not accompanied by sensory or motor effects.[39] If any symptom remains after 60 minutes, the state is known as persistent aura.[40]

Visual disturbances often consist of a

Sensory aura are the second most common type; they occur in 30–40% of people with auras.

Pain phase

Classically the headache is unilateral, throbbing, and moderate to severe in intensity.

The pain is frequently accompanied by nausea, vomiting,

Silent migraine

Sometimes, aura occurs without a subsequent headache.[39] This is known in modern classification as a typical aura without headache, or acephalgic migraine in previous classification, or commonly as a silent migraine.[52][53] However, silent migraine can still produce debilitating symptoms, with visual disturbance, vision loss in half of both eyes, alterations in color perception, and other sensory problems, like sensitivity to light, sound, and odors.[54] It can last from 15 to 30 minutes, usually no longer than 60 minutes, and it can recur or appear as an isolated event.[53]

Postdrome

The migraine postdrome could be defined as that constellation of symptoms occurring once the acute headache has settled.[55] Many report a sore feeling in the area where the migraine was, and some report impaired thinking for a few days after the headache has passed. The person may feel tired or "hung over" and have head pain, cognitive difficulties, gastrointestinal symptoms, mood changes, and weakness.[56] According to one summary, "Some people feel unusually refreshed or euphoric after an attack, whereas others note depression and malaise."[57][unreliable medical source?]

Cause

The underlying causes of migraines are unknown.[58] However, they are believed to be related to a mix of environmental and genetic factors.[3] They run in families in about two-thirds of cases[5] and rarely occur due to a single gene defect.[59] While migraines were once believed to be more common in those of high intelligence, this does not appear to be true.[46] A number of psychological conditions are associated, including depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.[60]

Success of the surgical migraine treatment by decompression of extracranial sensory nerves adjacent to vessels[61] suggests that migraineurs may have anatomical predisposition for neurovascular compression that may be caused by both intracranial and extracranial vasodilation due to migraine triggers. This, along with the existence of numerous cranial neural interconnections,[62] may explain the multiple cranial nerve involvement and consequent diversity of migraine symptoms.[63]

Genetics

Studies of twins indicate a 34% to 51% genetic influence of likelihood to develop migraine.[3] This genetic relationship is stronger for migraine with aura than for migraines without aura.[29] A number of specific variants of genes increase the risk by a small to moderate amount.[59]

Triggers

Migraine may be induced by triggers, with some reporting it as an influence in a minority of cases[5] and others the majority.[69] Many things such as fatigue, certain foods, alcohol, and weather have been labeled as triggers; however, the strength and significance of these relationships are uncertain.[69][70] Most people with migraines report experiencing triggers.[71] Symptoms may start up to 24 hours after a trigger.[5]

Physiological aspects

Common triggers quoted are stress, hunger, and fatigue (these equally contribute to

Dietary aspects

Between 12% and 60% of people report foods as triggers.[75][76]

There are many reports[77][78][79][80][81] that tyramine – which is naturally present in chocolate, alcoholic beverages, most cheeses, processed meats, and other foods – can trigger migraine symptoms in some individuals. Monosodium glutamate (MSG) has been reported as a trigger for migraine,[82] but a systematic review concluded that "a causal relationship between MSG and headache has not been proven... It would seem premature to conclude that the MSG present in food causes headache".[83]

Environmental aspects

A 2009 review on potential triggers in the indoor and outdoor environment concluded that while there were insufficient studies to confirm environmental factors as causing migraine, "migraineurs worldwide consistently report similar environmental triggers".[84]

Pathophysiology

Migraine is believed to be primarily a neurological disorder,

Sensitization of trigeminal pathways is a key pathophysiological phenomenon in migraine. It is debatable whether sensitization starts in the periphery or in the brain.[96][97]

Aura

Cortical spreading depression, or spreading depression according to Leão, is a burst of neuronal activity followed by a period of inactivity, which is seen in those with migraines with aura.[98] There are a number of explanations for its occurrence, including activation of NMDA receptors leading to calcium entering the cell.[98] After the burst of activity, the blood flow to the cerebral cortex in the area affected is decreased for two to six hours.[98] It is believed that when depolarization travels down the underside of the brain, nerves that sense pain in the head and neck are triggered.[98]

Pain

The exact mechanism of the head pain which occurs during a migraine episode is unknown.[99] Some evidence supports a primary role for central nervous system structures (such as the brainstem and diencephalon),[100] while other data support the role of peripheral activation (such as via the sensory nerves that surround blood vessels of the head and neck).[99] The potential candidate vessels include dural arteries, pial arteries and extracranial arteries such as those of the scalp.[99] The role of vasodilatation of the extracranial arteries, in particular, is believed to be significant.[101]

Neuromodulators

Calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRPs) have been found to play a role in the pathogenesis of the pain associated with migraine, as levels of it become elevated during an attack.[9][43]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a migraine is based on signs and symptoms.[5] Neuroimaging tests are not necessary to diagnose migraine, but may be used to find other causes of headaches in those whose examination and history do not confirm a migraine diagnosis.[106] It is believed that a substantial number of people with the condition remain undiagnosed.[5]

The diagnosis of migraine without aura, according to the International Headache Society, can be made according the "5, 4, 3, 2, 1 criteria," which is as follows:[13]

- Five or more attacks – for migraine with aura, two attacks are sufficient for diagnosis.

- Four hours to three days in duration

- Two or more of the following:

- Unilateral (affecting one side of the head)

- Pulsating

- Moderate or severe pain intensity

- Worsened by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity

- One or more of the following:

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Sensitivity to both light (photophobia) and sound (phonophobia)

If someone experiences two of the following: photophobia, nausea, or inability to work or study for a day, the diagnosis is more likely.[107] In those with four out of five of the following: pulsating headache, duration of 4–72 hours, pain on one side of the head, nausea, or symptoms that interfere with the person's life, the probability that this is a migraine attack is 92%.[9] In those with fewer than three of these symptoms, the probability is 17%.[9]

Classification

Migraine was first comprehensively classified in 1988.[29]

The

Migraine is divided into six subclasses (some of which include further subdivisions):[110]

- Migraine without aura, or "common migraine", involves migraine headaches that are not accompanied by aura.

- Migraine with aura, or "classic migraine", usually involves migraine headaches accompanied by aura. Less commonly, aura can occur without a headache, or with a nonmigraine headache. Two other varieties are world spinning, ringing in ears, or a number of other brainstem-related symptoms, but not motor weakness. This type was initially believed to be due to spasms of the basilar artery, the artery that supplies the brainstem. Now that this mechanism is not believed to be primary, the symptomatic term migraine with brainstem aura (MBA) is preferred.[49] Retinal migraine(which is distinct from visual or optical migraine) involves migraine headaches accompanied by visual disturbances or even temporary blindness in one eye.

- Childhood periodic syndromes that are commonly precursors of migraine include cyclical vomiting (occasional intense periods of vomiting), abdominal migraine(abdominal pain, usually accompanied by nausea), and benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood (occasional attacks of vertigo).

- Complications of migraine describe migraine headaches and/or auras that are unusually long or unusually frequent, or associated with a seizure or brain lesion.

- Probable migraine describes conditions that have some characteristics of migraines, but where there is not enough evidence to diagnose it as a migraine with certainty (in the presence of concurrent medication overuse).

- Chronic migraine is a complication of migraines, and is a headache that fulfills diagnostic criteria for migraine headache and occurs for a greater time interval. Specifically, greater or equal to 15 days/month for longer than 3 months.[111]

Abdominal migraine

The diagnosis of

Differential diagnosis

Other conditions that can cause similar symptoms to a migraine headache include

Those with stable headaches that meet criteria for migraines should not receive neuroimaging to look for other intracranial disease.[114][115][116] This requires that other concerning findings such as papilledema (swelling of the optic disc) are not present. People with migraines are not at an increased risk of having another cause for severe headaches.[citation needed]

Prevention

Preventive treatments of migraine include medications, nutritional supplements, lifestyle alterations, and surgery. Prevention is recommended in those who have headaches more than two days a week, cannot tolerate the medications used to treat acute attacks, or those with severe attacks that are not easily controlled.[9] Recommended lifestyle changes include stopping tobacco use and reducing behaviors that interfere with sleep.[117]

The goal is to reduce the frequency, painfulness, and duration of migraine episodes, and to increase the effectiveness of abortive therapy.[118][119] Another reason for prevention is to avoid medication overuse headache. This is a common problem and can result in chronic daily headache.[120][121]

Medication

Preventive migraine medications are considered effective if they reduce the frequency or severity of the migraine attacks by at least 50%.

The beta blocker

Tentative evidence also supports the use of

The

Medications in the

Alternative therapies

Acupuncture has a small effect in reducing migraine frequency, compared to sham acupuncture, a practice where needles are placed randomly or do not penetrate the skin.[134] Physiotherapy, massage and relaxation, and chiropractic manipulation might be as effective as propranolol or topiramate in the prevention of migraine headaches; however, the research had some problems with methodology.[135][136] Another review, however, found evidence to support spinal manipulation to be poor and insufficient to support its use.[137]

Tentative evidence supports the use of stress reduction techniques such as cognitive behavioral therapy, biofeedback, and relaxation techniques.[72] Regular physical exercise may decrease the frequency.[42] Numerous psychological approaches have been developed that are aimed at preventing or reducing the frequency of migraine in adults including educational approaches, relaxation techniques, assistance in developing coping strategies, strategies to change the way one thinks of a migraine attack, and strategies to reduce symptoms.[138] Other strategies include: progressive muscle relaxation, biofeedback, behavioral training, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness-based interventions.[139] The medical evidence supporting the effectiveness of these types of psychological approaches is very limited.[138]

Among alternative medicines,

Feverfew has traditionally been used as a treatment for fever, headache and migraine, women's conditions such as difficulties in labour and regulation of menstruation, relief of stomach ache, toothache and insect bites. During the last decades, it has mainly been used for headache and as a preventive treatment for migraine.[145] The plant parts used for medicinal use are the dried leaves or the dried aerial parts. Several historical data supports feverfew's traditional medicinal uses.[146] In addition, several clinical studies have been performed assessing the efficacy and safety of feverfew monotherapy in the prevention of migraine.[147] The majority of the clinical trials favoured feverfew over placebo. The data also suggest that feverfew is associated with only mild and transient adverse effects. The frequency of migraine was positively affected after treatment with feverfew. Reduction of migraine severity was also reported after intake of feverfew and incidence of nausea and vomiting decreased significantly. No effect of feverfew was reported in one study.[147]

There is tentative evidence for melatonin as an add-on therapy for prevention and treatment of migraine.[148][149] The data on melatonin are mixed and certain studies have had negative results.[148] The reasons for the mixed findings are unclear but may stem from differences in study design and dosage.[148] Melatonin's possible mechanisms of action in migraine are not completely clear, but may include improved sleep, direct action on melatonin receptors in the brain, and anti-inflammatory properties.[148][150]

Devices and surgery

Medical devices, such as

Management

There are three main aspects of treatment: trigger avoidance, acute symptomatic control, and medication for prevention.

For children, ibuprofen helps decrease pain and is the initially recommended treatment.[160][161] Paracetamol does not appear to be effective in providing pain relief.[160] Triptans are effective, though there is a risk of causing minor side effects like taste disturbance, nasal symptoms, dizziness, fatigue, low energy, nausea, or vomiting.[160][162] Ibuprofen should be used less than half the days in a month and triptans less than a third of the days in a month to decrease the risk of medication overuse headache.[161]

Analgesics

Recommended initial treatment for those with mild to moderate symptoms are simple analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or the combination of paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen), aspirin, and caffeine, although caffeine overuse can be a contributor to migraine chronification as well as a migraine trigger for many patients.[9][163] Several NSAIDs, including diclofenac and ibuprofen, have evidence to support their use.[164][165] Aspirin (900 to 1000 mg) can relieve moderate to severe migraine pain, with an effectiveness similar to sumatriptan.[166] Ketorolac is available in intravenous and intramuscular formulations.[9]

Paracetamol, either alone or in combination with

Naproxen by itself may not be effective as a stand-alone medicine to stop a migraine headache as it is only weakly better than a placebo medication in clinical trials.[170]

Antiemetics

Triptans

Most side effects are mild, including

Sumatriptan does not prevent other migraine headaches from starting in the future.[174] For increased effectiveness at stopping migraine symptoms, a combined therapy that includes sumatriptan and naproxen may be suggested.[178]

CGRP receptor antagonists

Calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonists (CGRP) target calcitonin gene-related peptide or its receptor to prevent migraine headaches or reduce their severity.[38] CGRP is a signaling molecule as well as a potent vasodilator that is involved in the development of a migraine headache.[38] There are four injectable monoclonal antibodies that target CGRP or its receptor (eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab) and the medications have demonstrated efficacy in the preventative treatment of episodic and chronic migraine headaches in phase III randomized clinical trials.[38]

Zavegepant was approved for medical use in the United States in March 2023.[179][180][181]

Ergotamines

Ergotamine and dihydroergotamine are older medications still prescribed for migraines, the latter in nasal spray and injectable forms.[5][182] They appear equally effective to the triptans[183] and experience adverse effects that typically are benign.[184] In the most severe cases, such as those with status migrainosus, they appear to be the most effective treatment option.[184] They can cause vasospasm including coronary vasospasm and are contraindicated in people with coronary artery disease.[185]

Magnesium

Magnesium is recognized as an inexpensive, over-the-counter supplement which can be part of a multimodal approach to migraine reduction. Some studies have shown to be effective in both preventing and treating migraine in intravenous form.[186] The intravenous form reduces attacks as measured in approximately 15–45 minutes, 120 minutes, and 24-hour time periods, magnesium taken orally alleviates the frequency and intensity of migraines.[187][188]

Other

Intravenous

Occipital nerve stimulation, may be effective but has the downsides of being cost-expensive and has a significant amount of complications.[191]

There is modest evidence for the effectiveness of non-invasive neuromodulatory devices, behavioral therapies and

Feverfew is registered as a traditional herbal medicine in the Nordic countries under the brand name Glitinum, only powdered feverfew is approved in the Herbal community monograph issued by European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Topiramate and botulinum toxin (Botox) have evidence in treating chronic migraine.[131][192] Botulinum toxin has been found to be useful in those with chronic migraine but not those with episodic ones.[193][194] The anti-CGRP monoclonal antibody erenumab was found in one study to decrease chronic migraines by 2.4 days more than placebo.[195]

Prognosis

"Migraine exists on a continuum of different attack frequencies and associated levels of disability."[196] For those with occasional, episodic migraine, a "proper combination of drugs for prevention and treatment of migraine attacks" can limit the disease's impact on patients' personal and professional lives.[197] But fewer than half of people with migraine seek medical care and more than half go undiagnosed and undertreated.[198] "Responsive prevention and treatment of migraine is incredibly important" because evidence shows "an increased sensitivity after each successive attack, eventually leading to chronic daily migraine in some individuals."[197] Repeated migraine results in "reorganization of brain circuitry," causing "profound functional as well as structural changes in the brain."[199] "One of the most important problems in clinical migraine is the progression from an intermittent, self-limited inconvenience to a life-changing disorder of chronic pain, sensory amplification, and autonomic and affective disruption. This progression, sometimes termed chronification in the migraine literature, is common, affecting 3% of migraineurs in a given year, such that 8% of migraineurs have chronic migraine in any given year." Brain imagery reveals that the electrophysiological changes seen during an attack become permanent in people with chronic migraine; "thus, from an electrophysiological point of view, chronic migraine indeed resembles a never-ending migraine attack."[199] Severe migraine ranks in the highest category of disability, according to the World Health Organization, which uses objective metrics to determine disability burden for the authoritative annual Global Burden of Disease report. The report classifies severe migraine alongside severe depression, active psychosis, quadriplegia, and terminal-stage cancer.[200]

Migraine with aura appears to be a risk factor for

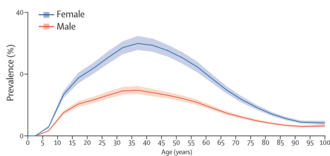

Epidemiology

Migraine is common, with around 33% of women and 18% of men affected at some point in their lifetime.[208] Onset can be at any age, but prevalence rises sharply around puberty, and remains high until declining after age 50.[208] Before puberty, boys and girls are equally impacted, with around 5% of children experiencing migraines. From puberty onwards, women experience migraines at greater rates than men. From age 30 to 50, up to 4 times as many women experience migraines as men.[208]

Worldwide, migraine affects nearly 15% or approximately one billion people.[10] In the United States, about 6% of men and 18% of women experience a migraine attack in a given year, with a lifetime risk of about 18% and 43% respectively.[5] In Europe, migraines affect 12–28% of people at some point in their lives with about 6–15% of adult men and 14–35% of adult women getting at least one yearly.[209] Rates of migraine are slightly lower in Asia and Africa than in Western countries.[46][210] Chronic migraine occurs in approximately 1.4 to 2.2% of the population.[211]

In women, migraine without aura are more common than migraine with aura; however in men the two types occur with similar frequency.[46]

During

History

An early description consistent with migraine is contained in the Ebers Papyrus, written around 1500 BCE in ancient Egypt.[213]

The word migraine is from the Greek ἡμικρᾱνίᾱ (hēmikrāníā), 'pain in half of the head',[214] from ἡμι- (hēmi-), 'half' and κρᾱνίον (krāníon), 'skull'.[215]

In 200 BCE, writings from the Hippocratic school of medicine described the visual aura that can precede the headache and a partial relief occurring through vomiting.[216]

A second-century description by

While many treatments for migraine have been attempted, it was not until 1868 that use of a substance which eventually turned out to be effective began.[216] This substance was the fungus ergot from which ergotamine was isolated in 1918.[223] Methysergide was developed in 1959 and the first triptan, sumatriptan, was developed in 1988.[223] During the 20th century with better study-design, effective preventive measures were found and confirmed.[216]

Society and culture

Migraine is a significant source of both medical costs and lost productivity. It has been estimated that migraine is the most costly neurological disorder in the European Community, costing more than €27 billion per year.

Research

Potential prevention mechanisms

Potential sex dependency

While no definitive proof has been found linking migraine to sex, statistical data indicates that women may be more prone to having migraine, showing migraine incidence three times higher among women than men.[230][231] The Society for Women's Health Research has also mentioned hormonal influences, mainly estrogen, as having a considerable role in provoking migraine pain. Studies and research related to the sex dependencies of migraine are still ongoing, and conclusions have yet to be achieved.[232][233][234]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e "Headache disorders Fact sheet N°277". October 2012. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ ISBN 9780071664332.

- ^ PMID 18058067.

- PMID 19289228.

- ^ PMID 20572569.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-5400-2. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Cluster Headache". American Migraine Foundation. 15 February 2017. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ PMID 21302868.

- ^ PMID 23245607.

- ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ PMID 14979299.

- ^ PMID 22083262.

- from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- from the original on 28 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- PMID 30127722.

- PMID 27312704.

- PMID 25926442.

- from the original on 4 July 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- PMID 24347803.

- from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- PMID 36475060.

- ^ Gobel H. "1. Migraine". ICHD-3 The International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- PMID 28919117.

- S2CID 34805084.

- ISBN 9781556428005. Archivedfrom the original on 12 March 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-5400-2. Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-5400-2. Archivedfrom the original on 22 December 2016.

- S2CID 35451906.

- ^ ISBN 9780683307238. Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2017.

- PMID 16483458.

- PMID 16483459.

- ISBN 9780071499927.

- PMID 31466456.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-148480-0.

- ^ S2CID 227078662.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-5400-2. Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2017.

- PMID 30171359.

- ISBN 9780323040730. Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ PMID 30203180.

- ^ S2CID 213191464.

- ISBN 9781461401780. Archivedfrom the original on 22 December 2016.

- S2CID 23256755.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-5400-2. Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2017.

- ISBN 9780195135183.

- ^ ISBN 9781405157384.

- ^ S2CID 22242504.

- ^ ISBN 9780781717298. Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ ISBN 9780781769471. Archivedfrom the original on 12 March 2017.

- ^ Robblee J (21 August 2019). "Silent Migraine: A Guide". American Migraine Foundation. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ PMID 25884682.

- ^ Leonard J (7 September 2018). Han S (ed.). "Silent migraine: Symptoms, causes, treatment, prevention". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- S2CID 22445093.

- S2CID 21519111.

- ISBN 978-1-888799-83-5. NBK7326. Archived from the originalon 27 August 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- S2CID 260317083.

- ^ PMID 22072275.

- ^ The Headaches, pp. 246–247

- S2CID 208273535.

- PMID 32289703.

- PMID 36078174.

- S2CID 20119237.

- S2CID 207195127.

- ^ PMID 23618705.

- S2CID 34902092.

- PMID 27634619.

- ^ S2CID 31707887.

- S2CID 5511782.

- S2CID 25016889.

- ^ PMID 23608071.

- PMID 19728969.

- PMID 24792340.

- S2CID 19582697.

- PMID 22646127.

- PMID 6527752.

- PMID 4559027.

- ^ "Tyramine and Migraines: What You Need to Know". excedrin.com. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-12-227055-0.

- (PDF) from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- S2CID 3042635. Archived from the original(PDF) on 13 August 2017.

- PMID 27189588.

- S2CID 29764274.

- PMID 31870279.

- ^ "Migraine". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 11 July 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- PMID 28948863.

- PMID 20216215.

- ^ Spiri D, Titomanlio L, Pogliani L, Zuccotti G (January 2012). "Pathophysiology of migraine: The neurovascular theory". Headaches: Causes, Treatment and Prevention: 51–64.

- PMID 19098031.

- S2CID 6272233.

- PMID 31679956.

- PMID 27312704.

- PMID 30127722.

- PMID 18666680.

- S2CID 214320892.

- PMID 36627561.

- ^ a b c d The Headaches, Chp. 28, pp. 269–72

- ^ S2CID 20452008.

- S2CID 8472711.

- S2CID 6939786.

- ^ PMID 26920010.

- ISBN 978-0-19-803135-2. Archivedfrom the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- PMID 29067618.

- S2CID 26543041.

- ^

- Lewis DW, Dorbad D (September 2000). "The utility of neuroimaging in the evaluation of children with migraine or chronic daily headache who have normal neurological examinations". Headache. 40 (8): 629–32. S2CID 14443890.

- Silberstein SD (September 2000). "Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 55 (6): 754–62. PMID 10993991.

- Medical Advisory Secretariat (2010). "Neuroimaging for the evaluation of chronic headaches: an evidence-based analysis". Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series. 10 (26): 1–57. PMID 23074404.

- Lewis DW, Dorbad D (September 2000). "The utility of neuroimaging in the evaluation of children with migraine or chronic daily headache who have normal neurological examinations". Headache. 40 (8): 629–32.

- S2CID 205684294.

- PMID 29368949.

- PMID 16362664.

- PMID 29368949.

- PMID 22288302.

- ^ ISBN 9780195137057. Archivedfrom the original on 22 December 2016.

- S2CID 12289726.

- S2CID 14443890.

- PMID 10993991.

- PMID 23074404.

- ^ PMID 31413170.

- from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- S2CID 43840120.

- S2CID 23422679.

- ^ Kaniecki R, Lucas S (2004). "Treatment of primary headache: preventive treatment of migraine". Standards of care for headache diagnosis and treatment. Chicago: National Headache Foundation. pp. 40–52.

- ^ S2CID 540800.

- PMID 23797674.

- PMID 32040139.

- S2CID 28302667.

- S2CID 202557362.

- PMID 22241949.

- S2CID 31097792.

- S2CID 25398410.

- ^ PMID 22529202.

- PMID 23592242.

- from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- PMID 27351677.

- PMID 21298314.

- S2CID 19155758.

- ^ S2CID 31205541.

- ^ PMID 31264211.

- ^ "Behavioral Interventions for Migraine Prevention (A Systematic Review)". Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. 14 July 2022. Archived from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- PMID 22529203.

- PMID 22683887.

- ^ "Butterbur: Uses, Side Effects, Interactions, Dosage, and Warning". webmd.com. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ "Butterbur". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). 8 February 2012. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- S2CID 25010508.

- PMID 1475370.

- ^ Barnes J, Anderson LA, Philipson JD (2007). Herbal Medicines (3rd ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press.

- ^ a b EMA. "Assessment report on Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Schultz Bip., herba" (PDF). Europa (web portal). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ PMID 27316772.

- PMID 30653130.

- S2CID 33548757.

- S2CID 23351902.

- S2CID 29122354.

- PMID 20816443.

- S2CID 18639211.

- ^ "FDA allows marketing of first medical device to prevent migraine headaches". Food and Drug Administration (Press release). 11 March 2014. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ "FDA approves transcranial magnetic stimulator" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2014.

- PMID 29845369.

We found significant reduction of monthly headache days

- S2CID 18817383.

- ^ "American Headache Society Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". Choosing Wisely. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ PMID 27091010.

- ^ PMID 31413171.

- S2CID 215814011.

- PMID 32731623.

- PMID 23633348.

- PMID 23633360.

- PMID 23633350.

- PMID 23633349.

- PMID 25579820.

- ^ PMID 27300483.

- PMID 24142263.

- from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- S2CID 41613179.

- ^ PMID 22336868.

- ^ PMID 22336867.

- ^ PMID 22336869.

- ^ a b "Generic migraine drug could relieve your pain and save you money". Best Buy Drugs. Consumer Reports. Archived from the original on 4 August 2013.

- S2CID 36333666.

- PMID 27096438.

- ^ "Zavzpret- zavegepant spray". DailyMed. 9 March 2023. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Zavzpret". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 April 2023. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Pfizer's Zavzpret (zavegepant) Migraine Nasal Spray Receives FDA Approval" (Press release). Pfizer. 10 March 2023. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023 – via businesswire.com.

- ^ from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- S2CID 45767513.

- ^ S2CID 44639896.

- PMID 10611116.

- from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- PMID 26752497.

- from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- PMID 18541610.

- PMID 31621134.

- S2CID 52923061.

- PMID 29939406.

- PMID 22535858.

- PMID 27164716.

- S2CID 49559342.

- S2CID 53114546.

- ^ a b "Migraine Information Page: Prognosis" Archived 10 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine, National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Institutes of Health (US).

- ^ "Key facts and figures about migraine". The Migraine Trust. 2017. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ PMID 29518355.

- ^ World Health Organization (2008). "Disability classes for the Global Burden of Disease study" (table 8), The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update Archived 13 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, p 33.

- ^ PMID 19861375.

- S2CID 31939284.

- PMID 21511950.

- S2CID 27227332.

- PMID 21803936.

- S2CID 46681674.

- PMID 24751961.

- ^ S2CID 245883895.

- S2CID 7490176.

- S2CID 24939546.

- S2CID 5328642.

- S2CID 23204921.

- ^ ISBN 9780781748117. Archivedfrom the original on 12 March 2017.

- ^ Liddell HG, Scott R. "ἡμικρανία". A Greek-English Lexicon. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. on Perseus

- ISBN 978-0-8151-6111-0.

- ^ ISBN 9780199754564. Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ ISBN 9781437736038. Archivedfrom the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "Sex(ism), Drugs, and Migraines". Distillations. Science History Institute. 15 January 2019. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ISBN 9780521691468. Archivedfrom the original on 17 June 2013.

- ISBN 9781935345039.

- ISBN 9781449069629. Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2017.

- OCLC 1259297708. Archivedfrom the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ S2CID 31940152.

- ^ PMID 18418547.

- ^ PMID 18604472.

- PMID 22543428.

- S2CID 42537455.

- S2CID 3805337.

- PMID 30974836.

- PMID 30155469.

- PMID 1727198.

- ^ "Speeding Progress in Migraine Requires Unraveling Sex Differences". SWHR. 28 August 2018. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Smith L (11 March 2021). Hamilton K (ed.). "Migraine in Women Needs More Sex-Specific Research". Migraine Again. Archived from the original on 12 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- S2CID 52048078.

Further reading

- Ashina M (November 2020). Ropper AH (ed.). "Migraine". The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (19): 1866–1876. S2CID 227078662.

- Oskoui M, Pringsheim T, Billinghurst L, Potrebic S, Gersz EM, Gloss D, et al. (September 2019). "Practice guideline update summary: Pharmacologic treatment for pediatric migraine prevention: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 93 (11): 500–509. PMID 31413170.

- Oskoui M, Pringsheim T, Holler-Managan Y, Potrebic S, Billinghurst L, Gloss D, et al. (September 2019). "Practice guideline update summary: Acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 93 (11): 487–499. S2CID 199662718.

External links

| External audio | |

|---|---|

- Migraine at Curlie