Military history of Armenia

| History of Armenia |

|---|

|

| Timeline • Origins • Etymology |

The early military history of Armenia is defined by the situation of the

From the early 16th century,

After losing the war in 1828 Qajar Iran ceded Eastern Armenia to the Russian Empire. Thus, from 1828 and on, historical Armenia was again situated between two empires, this time the Ottoman Empire vs. the Russian Empire. During the events of the Armenian genocide, many Armenians resisted the actions of the Turkish government and took up arms.

In 1991, when, following the

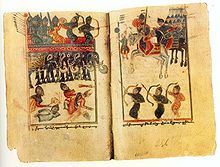

Early history

Armani

The Armani are mentioned to have fought the Akkadian Empire and to have a city sacked but not much more is known about the campaigns and wars between the nations nor the Armani nation itself.[citation needed]

Mitanni

After a few successful clashes with the Egyptians over the control of Syria, Mitanni sought peace with them, and an alliance was formed. During the reign of Shuttarna II, in the early 14th century BC, the relationship was very amicable, and he sent his daughter Gilu-Hepa to Egypt for a marriage with Pharaoh Amenhotep III. Mitanni was now at its peak of power.

However, by the reign of Eriba-Adad I (1390–1366 BC) Mitanni influence over Assyria was on the wane. Eriba-Adad I became involved in a dynastic battle between Tushratta and his brother Artatama II and after this his son Shuttarna II, who called himself king of the Hurri while seeking support from the Assyrians. A pro-Hurri/Assyria faction appeared at the royal Mitanni court. Eriba-Adad I had thus loosened Mitanni influence over Assyria, and in turn had now made Assyria an influence over Mitanni affairs. King Ashur-Uballit I (1365–1330 BC) of Assyria attacked Shuttarna and annexed Mitanni territory in the middle of the 14th century BC, making Assyria once more a great power.

At the death of Shuttarna, Mitanni was ravaged by a war of succession. Eventually Tushratta, a son of Shuttarna, ascended the throne, but the kingdom had been weakened considerably and both the Hittite and Assyrian threats increased. At the same time, the diplomatic relationship with Egypt went cold, the Egyptians fearing the growing power of the Hittites and Assyrians. The Hittite king Suppiluliuma I invaded the Mitanni vassal states in northern Syria and replaced them with loyal subjects.

In the capital Washukanni, a new power struggle broke out. The Hittites and the Assyrians supported different pretenders to the throne. Finally a Hittite army conquered the capital Washukanni and installed Shattiwaza, the son of Tushratta, as their vassal king of Mitanni in the late 14th century BC. The kingdom had by now been reduced to the Khabur Valley. The Assyrians had not given up their claim on Mitanni, and in the 13th century BC, Shalmaneser I annexed the kingdom.

Nairi, Shupria and Hayassa

The Nairi, Shupria and Hayassa tribes are a successive continuation of Armenian confederations that fought the Assyrians and Hittites for almost 500 years going from periods of vassalisation and infighting to periods of fierce campaigns against the Hittites causing a lot of trouble. There are mentions of 40 kings confirming the fact that this was a confederation of kingdoms who had to pay tribute to the Assyrians

Urartu

Urartu (Biainili in Urartian) was an ancient kingdom in the mountainous plateau between Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, and Caucasus mountains, later known as the Armenian Highland, and it centered around Lake Van (present-day eastern Turkey). The kingdom existed from about 1000 BC, or earlier, until 585 BC. The name corresponds to the Biblical Ararat.

Urartu was often called the "Kingdom of Ararat" in many ancient manuscripts and holy writings of different nations. The reason for uncertainty in the names (i.e. Urartu and Ararat) is due to variations in sources. In fact, the written languages at that time employed only consonants and not vowels. So the word itself in various ancient sources is written as "RRT", which could be either Ararat, or Urartu, or Uruarti and so on (for more on the name's etymology, see the section Name below).

Ancient sources have sometimes used "Armenia" and "Urartu" interchangeably to refer to the same country. For example, in the trilingual Behistun inscription, carved in 520 BC by the order of Darius the Great of Persia the country is referred to as Arminia in Old Persian, translated as Harminuia in Elamite and Urartu in Babylonian.

Furthermore, the kingdom was known as Armenia to the Greeks (and, subsequently, to the Roman Empire) living in western Anatolia, possibly due to the fact that the contacts they had with Urartu, were through the people of the tribe of Armen.

The kingdom fought mainly with the Assyrians and under Sarduri II and Argishti II defeated the Assyrians and drove them to their heartlands, cutting them off North and East. Their successors however would prove incapable of maintaining the Empire and after the death of Argishti II the Empire lost a successive war to Assyria and would later become a vassal of the Medes.

Antiquity

Artaxiad dynasty

An Armenian

The army of Tigranes II

According to the author of

Note that the numbers given by Israelite historians of the time were probably exaggerated, considering the fact that the

Plutarch wrote that the Armenian archers could kill from 200 meters with their deadly accurate arrows. The Romans admired and respected the bravery and the warrior spirit of the Armenian Cavalry -- the hardcore of Tigran's Army. The Roman historian Sallustius Crispus wrote that the Armenian [Ayrudzi - lit. horsemen] Cavalry was "remarkable by the beauty of their horses and armor" Horses in Armenia, since ancient times were considered as the most important part and pride of the warrior.[2][unreliable source?]

Armenian cavalry

Armenian horsemen were used by both Armenia, and also by nearby kingdoms or empires such as

Chapot wrote:

"What they say about Armenia bewilders us. How could this mountain people develop such a cavalry that was able to measure itself against the horsemen of the Medes? One thing which is certain is the fact that Armenia was a source of excellent well bred horses. The people in this country had discovered that horses were not just an economic asset, but could also be used for military purposes."[3]

In

Early Middle Ages

Armenia in the Byzantine Empire

During the Byzantine occupation of Western Armenia, the Armenians were considered an important element of the Byzantine army. As a result, they were encouraged to settle in distant regions of the Byzantine Empire in order to serve there. For example, in the 6th century,

In sixth century Narses, one of great generals of Justinian I, along with other victories succeeded in reconquering Italy from Ostgoths.

Traditional Armenian arms and armour

"

Bagratid Kingdom of Armenia

Following Byzantine occupation of

In Armenia, local nakharars were able to raise 25,000 to 40,000 men, but such a levy was rare. The country was strongly fortified. It is said that seventy castles defended the province of Vaspurakan, near Lake Van. There existed a special regiment of mountaineers who were trained to roll rocks onto their foes. In siege warfare, Armenians used iron hooks to help them climb fortification walls, and large leather shields to protect them from anything that would be dropped from above. Each nakharar led a force of free men under his own coat-of-arms. Armenians were well equipped for the time, as their country was rich in iron. The Armenian army also consisted of heavy cavalry called Ayruzdi. These Ayruzdi were said to be the strongest cavalry force of the time. Levies were recruited from the commoners in Armenia. Christian Armenian levies would fight for Christianity for any of the Christian armies of the time. It is said that most of Vartan Mamikonian's army were Christian levies[5]

Fortifications of Ani

During the reign of King

High Middle Ages

Involvement in the Byzantine army

In the late tenth and early eleventh centuries, Armenian involvement in the Byzantine army came from three different sources: "allied" contingents from

When the Byzantine Empire took over

Involvement in the Egyptian army

Although most Armenians were Christians, they played a significant role in nearby Muslim nations, such as

Georgian rule

Armenia was occupied by the Great

In 1195 when

Around the year 1199, they took the city of

Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia

The

According to contemporary chroniclers, there were up to 100,000 men in the Cilician Armenian army, a third of which was cavalry. At the time, Armenian heavy cavalry bore heavy resemblances to their Frankish counterparts, and the equipment used by the Armenian army was more and more akin to that used by the Europeans.[12] The Armenians provided great help in the Crusaders' military campaigns in the Levant. In fact, the Crusaders employed Armenian siege engineers throughout their campaigns. For example, a certain specialist named "Havedic" (Latinized form of "Avedis") designed the machines used to attack Tyre in 1124.[6]

Leo II introduced important changes in Cilician Armenian military organization, which until then was similar to that the Armenian kingdoms of Greater Armenia. The "nakharars", Armenian feudal nobles, lost much of their old autonomy. The names and functions of regional leaders were Latinized, and many facets of the army structure were inspired or copied from the Crusader states, particularly from the nearby principality of Antioch.[6]

Fortifications in Cilician Armenia

Most Armenian fortification in Cilicia are characterized by multiple bailey walls laid with irregular plans to follow the sinuosities of the outcrops, rounded and especially horseshoe-shaped towers, finely-cut often rusticated ashlar facing stones, a complex bent entrance with a slot machicolation, embrasured loopholes for archers, barrel or pointed vaults over undercrofts, gates and chapels, and cisterns with elaborate scarped drains.[13] In the immediate proximity of many fortifications are the remains of civilian settlements.[14] Some of the important castles in the Armenian Kingdom include: Sis, Anavarza, Vahka, Yılankale, Sarvandikar, Kuklak, T‛il Hamtun, Hadjin, Lampron, and Gaban (modern Geben).[15] Armenian design ideas influenced castle building in nearby Crusader states, such as the Principality of Antioch, where fortifications ranged from tiny hilltop outposts to major garrison fortresses. Antioch attracted few European settlers, and thus they relied heavily on military elites of Greek, Syrian, and Armenian origin, who probably influenced the design of local fortifications.[16]

Ottoman-Iranian Rule

In 1375, the

Armenian militia

The

World War I

The Armenian people were subjected to a

With the establishment of the

Aftermath

In 1920, Armenia fought a series of battles with

World War II

Armenia participated in the Second World War on the side of the Allies under the Soviet Union. Armenia was spared the devastation and destruction that wrought most of the western Soviet Union during the Great Patriotic War of World War II. The Nazis never reached the South Caucasus, which they intended to do in order to capture the oil fields in Azerbaijan. Still, Armenia played a valuable role in aiding the allies both through industry and agriculture. An estimated 300–500,000 Armenians served in the war, almost half of whom did not return.[19] Armenia thus had one of the highest death tolls, per capita, among the other Soviet republics.

Bagramyan, Isakov, Babadzhanian, Khudyakov

A total of 117 citizens of

Six special military divisions were formed in Soviet Armenia in 1941–42, partly because so many draftees from the republic could not understand Russian. These six divisions alone had more than 67,000 soldiers. Five of them, the 89th,

The

Outside of Armenia and the Soviet Union,

On the Axis side, the

An estimated 600,000 Armenians served in the

As of 2005[update], some 9,000 veterans of the war were still living in Armenia.[20]

Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh Republic)

During the 20th century, Nagorno-Karabakh had been denied an Armenian identity by the succeeding Russian, British, and Azeri rulers.[28]

The Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh had accused the Soviet Azerbaijani government of conducting forced ethnic cleansing of the region. The majority Armenian population, with ideological and material support from Armenia, started a movement to transfer the territory to Armenia. The issue was at first a "war of words" in 1987. In a December 1991 referendum, the people of Nagorno-Karabakh approved the creation of an independent state. A Soviet proposal for enhanced autonomy for Nagorno-Karabakh within Azerbaijan satisfied neither side. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, a war for independence of the Republic of Artsakh erupted between the Armenians and Azerbaijan, which claimed the area.

In the post-Soviet power vacuum, military action between Azerbaijan and Armenia was heavily influenced by the

By the end of 1993, the conflict had caused thousands of casualties and created hundreds of thousands of refugees on both sides. By May 1994 the Armenians were in control of 14% of the territory of Azerbaijan. As a result, the Azerbaijanis started direct negotiations with the Karabakhi authorities. A cease-fire was reached on May 12, 1994, through Russian negotiation. But, a final resolution to the conflict has yet to be realized.

Timeline of notable events

Victories are in light gray, losses are in red.

See also

- Armed Forces of Armenia

- Armenian Air Force

- History of Armenia

- List of wars involving Armenia

- Military history of the Republic of Artsakh

References

- ISBN 88-8057-226-1.

- ^ Gevork Nazaryan, Armenian Empire.

- ^ V. Chapot, La frontière de l'Euphrate de Pompée à la Conquète arabe, Paris, 1907, p. 17

- ISBN 1-84176-713-1.

- ^ ISBN 1-85532-224-2.

- ^ ISBN 0-85045-682-7.

- ^ Armenian Architecture – VirtualANI – The Lion Gate

- ^ ISBN 2-85944-448-3.

- ^ a b Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Badmoutioun Hayots, Volume II (in Armenian). Athens, Greece: Hradaragoutioun Azkayin Oussoumnagan Khorhourti. pp. 29–44.

- ISBN 0-85045-448-4.

- ISBN 0-521-05735-3. [verification needed]

- ^ "Le royaume arménien de Cilicie". Histoire-fr.com. Retrieved June 19, 2010.

- ISBN 0-88402-163-7.

- ^ Edwards, Robert W., “Settlements and Toponymy in Armenian Cilicia,” Revue des Études Arméniennes 24, 1993, pp.181-204.

- ^ Extensive photographic survey with plans of Armenian castles in Cilicia [1]

- ISBN 1-84176-715-8.

- ^ Blow 2009, pp. 9–10.

- ISBN 1-85532-697-3.

- ISBN 0-7099-0210-7.

- ^ a b c d e Sanjian, Ara. "The Armenian Contribution to the Allied Victory in the Second World War, 19 April 2005 (in English)". academia.edu. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ "V-Day: Armenian leader attends WW II allies' parade in Red Square" Archived 2010-05-12 at the Wayback Machine. ArmeniaNow. May 9, 2010.

- ^ a b (in Armenian) Khudaverdyan, Konstantin. «Սովետական Միության Հայրենական Մեծ Պատերազմ, 1941–1945» ("The Soviet Union's Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945"). Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1984, pp. 542–547.

- ISBN 9780962294518.

- ^ "Obituary: Monique Agazarian". The Independent. 22 March 1993. Archived from the original on 2022-05-14. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ "Gevork Vartanyan". The Telegraph. 11 January 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

Gevork Vartanyan, who has died aged 87, worked for Soviet intelligence for more than half a century and played an important part in thwarting a Nazi plot to assassinate Churchill, Stalin and President Roosevelt at the Tehran Conference in 1943.

- ISBN 0-7658-0834-X.

- ^ Dallin, Alexander (1957). German Rule in Russia: 1941–1945: A Study of Occupation Policies. New York: St Martin's Press. pp. 229, 251.

- ISBN 90-411-0223-X.

- ^ ""The 'Afghan Alumni' Terrorism"". Archived from the original on 2001-11-30. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- ^ "Chechen Fighter's Death Reveals Conflicted Feelings in Azerbaijan" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, EurasiaNet

- ^ "Chechen Fighters". Archived from the original on 2010-07-16. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- ^ a b c Establishment, or naming these forces as DRA military will follow the deceleration of independence

Sources

- Blow, David (2009). Shah Abbas: The Ruthless King Who became an Iranian Legend. London, UK: I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd. LCCN 2009464064.

- Elishe: History of Vardan and the Armenian War, transl. R.W. Thomson, Cambridge, Mass. 1982

- Dr. Abd al-Husayn Zarrin’kub "Ruzgaran:tarikh-i Iran az aghz ta saqut saltnat Pahlvi" Sukhan, 1999. ISBN 964-6961-11-8

- Vahan Kurkjian - Period of the Marzbans — Battle of Avarair

- Gevork Nazaryan - The struggle for Religious Freedom

- de Waal, Thomas. Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press, 2003