Military settlement

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

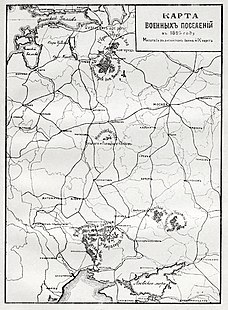

Military settlements (

The beginning of the reform

The Emperor

Internal organization

The quartered military forces were being formed from among married soldiers, who had already served in the army for no less than six years, and local men (mainly, peasants) between 18 and 45 years of age. Both of these categories were called master settlers (поселяне-хозяева). The rest of the locals of the same age, who had been fit for military service, but had not been chosen, were being enlisted as assistants to their masters and were a part of reserve military subdivisions.

The children (under age of 18) of the military settlers and the indigenous peasant population within the military settlement were enlisted in the cantonists, with military schooling starting at the age of 7 (later changed to 10). Upon reaching the age of 18, they were transferred to the military units. The settlers would retire at the age of 45 and continue to serve in hospitals and other establishments.[1]

Each military settlement consisted of 60 interconnected houses (дома-связи) with a

Organization of rural and agriculture activities was extremely bad. All the activities of military settlers were strictly specified by Arakcheyev’s instructions. These instructions paid little attention to season character of certain works or distance between military settlement and fields to be plowed. For example, sometimes it may be prescribed to make hay 7–10 miles away from the military settlement. Settlers had to spend a lot of time to get to their job and then back, so the work could not be done in time. If an instruction was not complied with, all the settlers had been severely punished no matter what reason they had for not to do the job in time. Sometimes the instruction strictly specified a certain day for a certain job, and if it was rainy at such day, the job could not be done. Since the instruction was not complied again, settlers got severe punishment. State officials including Arakcheyev knew little about agriculture. In Saint Petersburg area peasants had been practicing hunting, fishing, small artisan production, trade activities for a long time, because northern soil did not fit for agriculture. When military settlements had been implemented near Saint Petersburg, all the settlers had been prescribed to grow wheat and other activities out of law, this led to impoverishment of local population and malnourishment. Due to such circumstances the military performance of settlers was low. Overall, they were not effective as soldiers or agriculture workers.

Riots in military settlements

Military settlements never became an anti-

In July 1831, one of the largest military riots in the Russian army of the 1st half of the 19th century took place in a military settlement near Staraya Russa. It was caused by

Abolition

In 1831, many military settlements were renamed to communities of plowing soldiers (округа пахотных солдат), which would lead to an actual elimination of most of the military settlements. In 1857, all of the military settlements and okrugs of the plowing soldiers were abolished.[2]

See also

References

- ISBN 5518040083.

- ^ a b Снытко, О.В.; et al. (2009). Трифонов, С.Д.; Чуйкова, Т.Б.; Федина, Л.В.; Дубоносова, А.Э. (eds.). Административно-территориальное деление Новгородской губернии и области 1727-1995 гг. Справочник [Administrative-territorial division of the Novgorod province and region 1727-1995. Reference] (PDF) (in Russian). Saint Petersburg. p. 26. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)