Southern Min

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

| Southern Min | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ethnicity |

|

| Geographic distribution | |

| Linguistic classification | Sino-Tibetan

|

Early forms | |

| Subdivisions | |

BUC | Mìng-nàng-ngṳ̄ |

| Northern Min | |

| Jian'ou Romanized | Mâing-nâng-ngṳ̌ |

Southern Min (

The most widely spoken Southern Min language is Hokkien, which includes Taiwanese. Other varieties of Southern Min have significant differences from Hokkien, some having limited

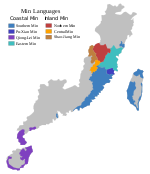

Geographic distribution

Mainland China

Southern Min dialects are spoken in

Taiwan

The Southern Min dialects spoken in Taiwan, collectively known as Taiwanese, is a first language for most of the Hoklo people, the main ethnicity of Taiwan. The correspondence between language and ethnicity is not absolute, as some Hoklo have very limited proficiency in Southern Min while some non-Hoklo speak Southern Min fluently.[7]

Southeast Asia

There are many Southern Min speakers among

Southern Min speakers form the majority of Chinese in Singapore, with Hokkien being the largest group and the second largest being Teochew. Despite the similarities, the two groups are rarely viewed together as "Southern Min".

Classification

The variants of Southern Min spoken in Zhejiang province are most akin to that spoken in Quanzhou. The variants spoken in Taiwan are similar to the three Fujian variants and are collectively known as Taiwanese.

Those Southern Min variants that are collectively known as "Hokkien" in

The Southern Min language variant spoken around

Varieties

There are two or three divisions of Southern Min, depending on the criteria for Leizhou and Hainanese inclusion:

More recently, Kwok (2018: 157)

Hokkien

Hokkien is the most widely spoken form of Southern Min, including

Chaoshan (Teo-Swa)

Teo-Swa or Chaoshan speech (潮汕片) is a closely related variant of Southern Min that includes the

Phonology

Southern Min has one of the most diverse phonologies of Chinese varieties, with more consonants than Mandarin or Cantonese. Vowels, on the other hand, are more-or-less similar to those of Mandarin. In general, Southern Min dialects have five to six tones, and tone sandhi is extensive. There are minor variations within Hokkien, and the Teochew system differs somewhat more.

Southern Min's

Writing systems

Both Hokkien and Chaoshan (

History

The Min homeland of Fujian was opened to Han Chinese settlement by the defeat of the

- The Jin dynasty, particularly the Disaster of Yongjiain 311 AD, caused a tide of immigration to the south.

- In 669, Chen Yuanguang from Gushi County in Henan set up a regional administration in Fujian to suppress an insurrection by the She people.

- Ten Kingdoms in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

Jerry Norman identifies four main layers in the vocabulary of modern Min varieties:

- A non-Chinese substratum from the

- The earliest Chinese layer, brought to Fujian by settlers from Zhejiang to the north during the Han dynasty.[18]

- A layer from the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, which is largely consistent with the phonology of the Qieyun dictionary.[19]

- A

Comparisons with Sino-Xenic character pronunciations

Southern Min can trace its origins through the

| English | Han characters | Mandarin Chinese | Hokkien[21] | Teochew | Cantonese | Korean | Vietnamese | Japanese |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Book | 冊 | cè | Chhek/Chheh | cêh4 | caak3 | Chaek (책) | Sách | Saku/Satsu/Shaku |

| Bridge | 橋 | qiáo | Kiâu/Kiô | giê5/gio5 | kiu4 | Gyo (교) | Kiều | Kyō |

| Dangerous | 危險 | wēixiǎn/wéixiǎn | Guî-hiám | guîn5/nguín5 hiem2 | ngai4 him2 | Wiheom (위험) | Nguy hiểm | Kiken |

| Embassy | 大使館 | Dàshǐguǎn | Tāi-sài-koán | dai6 sái2 guêng2 | daai6 si3 gun2 | Daesagwan (대사관) | Đại Sứ Quán | Taishikan |

| Flag | 旗 | Qí | Kî | kî5 | kei4 | Gi (기) | Kì | Ki |

| Insurance | 保險 | Bǎoxiǎn | Pó-hiám | Bó2-hiém | bou2 him2 | Boheom (보험) | Bảo hiểm | Hoken |

| News | 新聞 | Xīnwén | Sin-bûn | sing1 bhung6 | san1 man4 | Shinmun (신문) | Tân văn | Shinbun |

| Student | 學生 | Xuéshēng | Ha̍k-seng | Hak8 sêng1 | hok6 saang1 | Haksaeng (학생) | Học sinh | Gakusei |

| University | 大學 | Dàxué | Tāi-ha̍k/Tōa-o̍h | dai6 hag8/dua7 oh8 | daai6 hok6 | Daehak (대학) | Đại học | Daigaku |

See also

- Chinese in Singapore

- Languages of China

- Languages of Taiwan

- Languages of Thailand

- Malaysian Chinese

- Protection of the Varieties of Chinese

References

- JSTOR 2718766

- ISBN 978-0-7748-0192-8

- from the original on 2023-10-13. Retrieved 2023-10-13.

- ISBN 978-7533469511.

- ^ Southern Min at Ethnologue (23rd ed., 2020)

- ISBN 9780252032462.

- ^ "The politics of language names in Taiwan". www.ksc.kwansei.ac.jp. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- ISBN 978-1-138-94365-0.

- ^ Minnan/ Southern Min at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Norman (1991), pp. 328.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 210, 228.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 228–229.

- ^ Ting (1983), pp. 9–10.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 33, 79.

- ^ Yan (2006), p. 120.

- ^ Norman & Mei (1976).

- ^ Norman (1991), pp. 331–332.

- ^ Norman (1991), pp. 334–336.

- ^ Norman (1991), p. 336.

- ^ Norman (1991), p. 337.

- ^ Iûⁿ, Ún-giân. "Tâi-bûn/Hôa-bûn Sòaⁿ-téng Sû-tián" 台文/華文線頂辭典 [Taiwanese/Chinese Online Dictionary]. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

Sources

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2014), Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- JSTOR 40726203.

- ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- Norman, Jerry (1991), "The Mǐn dialects in historical perspective", in Wang, William S.-Y. (ed.), Languages and Dialects of China, Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series, vol. 3, Chinese University Press, pp. 325–360, OCLC 600555701.

- Ting, Pang-Hsin (1983), "Derivation time of colloquial Min from Archaic Chinese", Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, 54 (4): 1–14.

- Yan, Margaret Mian (2006), Introduction to Chinese Dialectology, LINCOM Europa, ISBN 978-3-89586-629-6.

Further reading

- Branner, David Prager (2000). Problems in Comparative Chinese Dialectology — the Classification of Miin and Hakka. Trends in Linguistics series, no. 123. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-015831-0.

- Chung, Raung-fu (1996). The segmental phonology of Southern Min in Taiwan. Taipei: Crane Pub. Co. ISBN 957-9463-46-8.

- DeBernardi, Jean (1991). "Linguistic nationalism: the case of Southern Min". OCLC 24810816.

- Chappell, Hilary, ed. (2001). Sinitic Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-829977-X. "Part V: Southern Min Grammar" (3 articles).

External links

- 當代泉州音字彙, a dictionary of Quanzhou speech

- Iûⁿ, Ún-giân (2006). "Tai-gi Hôa-gí Sòaⁿ-téng Sû-tián" 台文/華文線頂辭典 [On-line Taiwanese/Mandarin Dictionary] (in Chinese and Minnan).

- Iûⁿ, Ún-giân. 台語線頂字典 [Taiwanese Hokkien Online Character Dictionary] (in Minnan and Chinese (Taiwan)).

- 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典, Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan by the Ministry of Education, Republic of China (Taiwan).

- 臺灣本土語言互譯及語音合成系統, Taiwanese-Hakka-Mandarin online conversion

- Voyager - Spacecraft - Golden Record - Greetings from Earth - Amoy The voyager clip says: Thài-khong pêng-iú, lín-hó. Lín chia̍h-pá--bē? Ū-êng, to̍h lâi gún chia chē--ô·! 太空朋友,恁好。恁食飽未?有閒著來阮遮坐哦!

- 台語詞典 Taiwanese-English-Mandarin Dictionary

- "How to Forget Your Mother Tongue and Remember Your National Language" by Victor H. Mair, University of Pennsylvania

- ISO 639-3 Change Request Documentation: 2008-083, requesting to replace code nan (Minnan Chinese) with dzu (Chaozhou) and xim (Xiamen), rejected because it did not include codes to cover the rest of the group.

- ISO 639-3 Change Request Documentation: 2021-045, requesting to replace code

nanwith 11 new codes.- "Reclassifying ISO 639-3 [nan]: An Empirical Approach to Mutual Intelligibility and Ethnolinguistic Distinctions". GitHub. 18 December 2021. – supporting documentation