Ming dynasty

Great Ming

| |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1368–1644 | |||||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||

• 1368–1398 (first) | Hongwu Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

• 1402–1424 | Yongle Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

• 1572–1620 (longest) | Wanli Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

• 1627–1644 (last) | Chongzhen Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Fall of Beijing | 25 April 1644 | |||||||||||||||

• End of the Southern Ming[b] | 1662 | ||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||

| 1450[1][2] | 6,500,000 km2 (2,500,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||

• 1393[3] | 65,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||

• 1500[4] | 125,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||

• 1600[5] | 160,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||

| GDP (nominal) | estimate | ||||||||||||||||

• Per capita | |||||||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Ming dynasty | ||

|---|---|---|

Tâi-lô | Tāi-bîng | |

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

The Ming dynasty (/mɪŋ/ MING),[7] officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last imperial dynasty of China ruled by the Han people, the majority ethnic group in China. Although the primary capital of Beijing fell in 1644 to a rebellion led by Li Zicheng (who established the short-lived Shun dynasty), numerous rump regimes ruled by remnants of the Ming imperial family—collectively called the Southern Ming—survived until 1662.[c]

The Ming dynasty's founder, the

The rise of new emperors and new factions diminished such extravagances; the capture of the

By the 16th century, the

History

Founding

Revolt and rebel rivalry

The

With the

Reign of the Hongwu Emperor

Hongwu made an immediate effort to rebuild state infrastructure. He built a 48 km (30 mi) long wall around Nanjing, as well as new palaces and government halls.[15] The History of Ming states that as early as 1364 Zhu Yuanzhang had begun drafting a new Confucian law code, the Da Ming Lü, which was completed by 1397 and repeated certain clauses found in the old Tang Code of 653.[17] Hongwu organized a military system known as the weisuo, which was similar to the fubing system of the Tang dynasty (618–907).

In 1380 Hongwu had the Chancellor

The Hongwu Emperor issued many edicts forbidding Mongol practices and proclaiming his intention to purify China of barbarian influence. However, he also sought to use the Yuan legacy to legitimize his authority in China and other areas ruled by the Yuan. He continued policies of the Yuan dynasty such as continued request for Korean concubines and eunuchs, Mongol-style hereditary military institutions, Mongol-style clothing and hats, promoting archery and horseback riding, and having large numbers of Mongols serve in the Ming military. Until the late 16th century Mongols still constituted one-in-three officers serving in capital forces like the

Hongwu insisted that he was not a rebel, and he attempted to justify his conquest of the other rebel warlords by claiming that he was a Yuan subject and had been divinely-appointed to restore order by crushing rebels. Most Chinese elites did not view the Yuan's Mongol ethnicity as grounds to resist or reject it. Hongwu emphasised that he was not conquering territory from the Yuan dynasty but rather from the rebel warlords. He used this line of argument to attempt to persuade Yuan loyalists to join his cause.[23] The Ming used the tribute they received from former Yuan vassals as proof that the Ming had taken over the Yuan's legitimacy. Tribute missions were regularly celebrated with music and dance in the Ming court.[24]

South-Western frontier

Hui Muslim troops settled in

Campaign in the North-East

After the overthrow of the

The early Ming court could not, and did not, aspire to the control imposed upon the

Relations with Tibet

The Mingshi—the official history of the Ming dynasty compiled by the Qing dynasty in 1739—states that the Ming established itinerant commanderies overseeing Tibetan administration while also renewing titles of ex-Yuan dynasty officials from Tibet and conferring new princely titles on leaders of Tibetan Buddhist sects.[32] However, Turrell V. Wylie states that censorship in the Mingshi in favor of bolstering the Ming emperor's prestige and reputation at all costs obfuscates the nuanced history of Sino-Tibetan relations during the Ming era.[33]

Modern scholars debate whether the Ming dynasty had

The Ming sporadically sent armed forays into Tibet during the 14th century, which the Tibetans successfully resisted..

Reign of the Yongle Emperor

Rise to power

The

New capital and foreign engagement

Yongle demoted Nanjing to a secondary capital and in 1403 announced the new capital of China was to be at his power base in

Beginning in 1405, the Yongle Emperor entrusted his favored

Yongle used

Tumu Crisis and the Ming Mongols

The

While the

Decline

Reign of the Wanli Emperor

There were many problems—fiscal or other—facing Ming China that started during the reign of the

Role of eunuchs

The Hongwu Emperor forbade eunuchs to learn how to read or engage in politics. Whether or not these restrictions were carried out with absolute success in his reign, eunuchs during the Yongle Emperor's reign (1402–1424) and afterwards managed huge imperial workshops, commanded armies, and participated in matters of appointment and promotion of officials. Yongle put 75 eunuchs in charge of foreign policy; they traveled frequently to vassal states including Annam, Mongolia, the Ryukyu Islands, and Tibet and less frequently to farther-flung places like Japan and Nepal. In the later 15th century, however, eunuch envoys generally only traveled to Korea.[71]

The eunuchs developed their own bureaucracy that was organized parallel to but was not subject to the civil service bureaucracy.[72] Although there were several dictatorial eunuchs throughout the Ming, such as Wang Zhen, Wang Zhi, and Liu Jin, excessive tyrannical eunuch power did not become evident until the 1590s when the Wanli Emperor increased their rights over the civil bureaucracy and granted them power to collect provincial taxes.[65][73]

The eunuch Wei Zhongxian (1568–1627) dominated the court of the Tianqi Emperor (r. 1620–1627) and had his political rivals tortured to death, mostly the vocal critics from the faction of the Donglin Society. He ordered temples built in his honor throughout the Ming Empire, and built personal palaces created with funds allocated for building the previous emperor's tombs. His friends and family gained important positions without qualifications. Wei also published a historical work lambasting and belittling his political opponents.[74] The instability at court came right as natural calamity, pestilence, rebellion, and foreign invasion came to a peak. The Chongzhen Emperor (r. 1627–44) had Wei dismissed from court, which led to Wei's suicide shortly after.

The eunuchs built their own social structure, providing and gaining support to their birth clans. Instead of fathers promoting sons, it was a matter of uncles promoting nephews. The Heishanhui Society in Peking sponsored the temple that conducted rituals for worshiping the memory of Gang Tie, a powerful eunuch of the Yuan dynasty. The Temple became an influential base for highly placed eunuchs, and continued in a somewhat diminished role during the Qing dynasty.[75][76][77]

Economic breakdown and natural disasters

During the last years of the Wanli era and those of his two successors, an economic crisis developed that was centered on a sudden widespread lack of the empire's chief medium of exchange: silver.

Famines became common in northern China in the early 17th century because of unusually dry and cold weather that shortened the growing season—effects of a larger ecological event now known as the Little Ice Age.[89] Famine, alongside tax increases, widespread military desertions, a declining relief system, and natural disasters such as flooding and inability of the government to properly manage irrigation and flood-control projects caused widespread loss of life and normal civility.[89] The central government, starved of resources, could do very little to mitigate the effects of these calamities. Making matters worse, a widespread epidemic, the Great Plague of 1633–1644, spread across China from Zhejiang to Henan, killing an unknown but large number of people.[90] The deadliest earthquake of all time, the Shaanxi earthquake of 1556, occurred during the Jiajing Emperor's reign, killing approximately 830,000 people.[91]

Fall of the Ming

Rise of the Manchus

Originally a Ming vassal who officially considered himself a guardian of the Ming border and a local representative of imperial Ming power,[92] Nurhaci, leader of the Jianzhou Jurchens, unified other Jurchen clans to create a new Manchu ethnic identity. He offered to lead his armies to support Ming and Joseon armies against the Japanese invasions of Korea in the 1590s. Ming officials declined the offer, but granted him the title of dragon-tiger general for his gesture. Recognizing the weakness of Ming authority in Manchuria at the time, he consolidated power by co-opting or conquering surrounding territories. In 1616 he declared himself Khan and established the Later Jin dynasty in reference to the previous Jurchen-ruled Jin dynasty. In 1618 he openly renounced the Ming overlordship and effectively declared war against the Ming with the "Seven Grievances."[93]

In 1636, Nurhaci's son

Rebellion, invasion, collapse

A peasant soldier named Li Zicheng mutinied with his fellow soldiers in western Shaanxi in the early 1630s after the Ming government failed to ship much-needed supplies there.[89] In 1634 he was captured by a Ming general and released only on the terms that he return to service.[97] The agreement soon broke down when a local magistrate had thirty-six of his fellow rebels executed; Li's troops retaliated by killing the officials and continued to lead a rebellion based in Rongyang, central Henan province by 1635.[98] By the 1640s, an ex-soldier and rival to Li—Zhang Xianzhong (1606–1647)—had created a firm rebel base in Chengdu, Sichuan, with the establishment of the Xi dynasty, while Li's center of power was in Hubei with extended influence over Shaanxi and Henan.[98]

In 1640, masses of Chinese peasants who were starving, unable to pay their taxes, and no longer in fear of the frequently defeated Chinese army, began to form into huge bands of rebels. The Chinese military, caught between fruitless efforts to defeat the Manchu raiders from the north and huge peasant revolts in the provinces, essentially fell apart. Unpaid and unfed, the army was defeated by Li Zicheng—now self-styled as the Prince of

Seizing opportunity, the

Despite the loss of Beijing and the death of the emperor, the Ming were not yet totally destroyed. Nanjing, Fujian, Guangdong, Shanxi, and Yunnan were all strongholds of Ming resistance. However, there were several pretenders for the Ming throne, and their forces were divided. These scattered Ming remnants in southern China after 1644 were collectively designated by 19th-century historians as the

Government

Province, prefecture, sub-prefecture and county

Described as "one of the greatest eras of orderly government and social stability in human history" by

Institutions and bureaus

Institutional trends

Departing from the main central administrative system generally known as the

The Hongwu Emperor sent his heir apparent to Shaanxi in 1391 to "tour and soothe" (xunfu) the region; in 1421 the Yongle Emperor commissioned 26 officials to travel the empire and uphold similar investigatory and patrimonial duties. By 1430 these xunfu assignments became institutionalized as "

Although decentralization of state power within the provinces occurred in the early Ming, the trend of central government officials delegated to the provinces as virtual provincial governors began in the 1420s. By the late Ming dynasty, there were central government officials delegated to two or more provinces as supreme commanders and viceroys, a system which reined in the power and influence of the military by the civil establishment.[113]

Grand Secretariat and Six Ministries

- The Ministry of Personnel was in charge of appointments, merit ratings, promotions, and demotions of officials, as well as granting of honorific titles.[117]

- The Ministry of Revenue was in charge of gathering census data, collecting taxes, and handling state revenues, while there were two offices of currency that were subordinate to it.[118]

- The Ministry of Rites was in charge of state ceremonies, rituals, and sacrifices; it also oversaw registers for Buddhist and Daoist priesthoods and even the reception of envoys from tributary states.[119]

- The Ministry of War was in charge of the appointments, promotions, and demotions of military officers, the maintenance of military installations, equipment, and weapons, as well as the courier system.[120]

- The Ministry of Justice was in charge of judicial and penal processes, but had no supervisory role over the Censorate or the Grand Court of Revision.[121]

- The Ministry of Public Works had charge of government construction projects, hiring of artisans and laborers for temporary service, manufacturing government equipment, the maintenance of roads and canals, standardization of weights and measures, and the gathering of resources from the countryside.[121]

Bureaus and offices for the imperial household

The imperial household was staffed almost entirely by eunuchs and ladies with their own bureaus.[122] Female servants were organized into the Bureau of Palace Attendance, Bureau of Ceremonies, Bureau of Apparel, Bureau of Foodstuffs, Bureau of the Bedchamber, Bureau of Handicrafts, and Office of Staff Surveillance.[122] Starting in the 1420s, eunuchs began taking over these ladies' positions until only the Bureau of Apparel with its four subsidiary offices remained.[122] Hongwu had his eunuchs organized into the Directorate of Palace Attendants, but as eunuch power at court increased, so did their administrative offices, with eventual twelve directorates, four offices, and eight bureaus.[122] The dynasty had a vast imperial household, staffed with thousands of eunuchs, who were headed by the Directorate of Palace Attendants. The eunuchs were divided into different directorates in charge of staff surveillance, ceremonial rites, food, utensils, documents, stables, seals, apparel, and so on.[123] The offices were in charge of providing fuel, music, paper, and baths.[123] The bureaus were in charge of weapons, silverwork, laundering, headgear, bronze work, textile manufacture, wineries, and gardens.[123] At times, the most influential eunuch in the Directorate of Ceremonial acted as a de facto dictator over the state.[124]

Although the imperial household was staffed mostly by eunuchs and palace ladies, there was a civil service office called the Seal Office, which cooperated with eunuch agencies in maintaining imperial seals, tallies, and stamps.[125] There were also civil service offices to oversee the affairs of imperial princes.[126]

Personnel

Scholar-officials

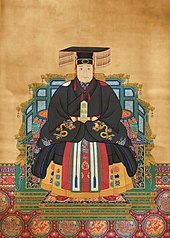

The Hongwu emperor from 1373 to 1384 staffed his bureaus with officials gathered through recommendations only. After that the scholar-officials who populated the many ranks of bureaucracy were recruited through a rigorous

As in earlier periods, the focus of the examination was classical Confucian texts, while the bulk of test material centered on the

The maximum tenure in office was nine years, but every three years officials were graded on their performance by senior officials. If they were graded as superior then they were promoted, if graded adequate then they retained their ranks, and if graded inadequate they were demoted one rank. In extreme cases, officials would be dismissed or punished. Only capital officials of grade 4 and above were exempt from the scrutiny of recorded evaluation, although they were expected to confess any of their faults. There were over 4,000 school instructors in county and prefectural schools who were subject to evaluations every nine years. The Chief Instructor on the prefectural level was classified as equal to a second-grade county graduate. The Supervisorate of Imperial Instruction oversaw the education of the heir apparent to the throne; this office was headed by a Grand Supervisor of Instruction, who was ranked as first class of grade three.[136]

Historians debate whether the examination system expanded or contracted upward social mobility. On the one hand, the exams were graded without regard to a candidate's social background, and were theoretically open to everyone.[f] In actual practice, the successful candidates had years of a very expensive, sophisticated tutoring of the sort that wealthy gentry families specialized in providing their talented sons. In practice, 90 percent of the population was ineligible due to lack of education, but the upper 10 percent had equal chances for moving to the top. To be successful young men had to have extensive, expensive training in classical Chinese, the use of Mandarin in spoken conversation, calligraphy, and had to master the intricate poetic requirements of the eight-legged essay. Not only did the traditional gentry dominated the system, they also learned that conservatism and resistance to new ideas was the path to success. For centuries critics had pointed out these problems, but the examination system only became more abstract and less relevant to the needs of China.[137] The consensus of scholars is that the eight-legged essay can be blamed as a major cause of "China's cultural stagnation and economic backwardness." However Benjamin Ellman argues there were some positive features, since the essay form was capable of fostering "abstract thinking, persuasiveness, and prosodic form" and that its elaborate structure discouraged a wandering, unfocused narrative".[138]

Lesser functionaries

Scholar-officials who entered civil service through examinations acted as executive officials to a much larger body of non-ranked personnel called lesser functionaries. They outnumbered officials by four to one; Charles Hucker estimates that they were perhaps as many as 100,000 throughout the empire. These lesser functionaries performed clerical and technical tasks for government agencies. Yet they should not be confused with lowly lictors, runners, and bearers; lesser functionaries were given periodic merit evaluations like officials and after nine years of service might be accepted into a low civil service rank.[139] The one great advantage of the lesser functionaries over officials was that officials were periodically rotated and assigned to different regional posts and had to rely on the good service and cooperation of the local lesser functionaries.[140]

Eunuchs, princes, and generals

Eunuchs gained unprecedented power over state affairs during the Ming dynasty. One of the most effective means of control was the secret service stationed in what was called the Eastern Depot at the beginning of the dynasty, later the Western Depot. This secret service was overseen by the Directorate of Ceremonial, hence this state organ's often totalitarian affiliation. Eunuchs had ranks that were equivalent to civil service ranks, only theirs had four grades instead of nine.[141][142]

Descendants of the first Ming emperor were made princes and given (typically nominal) military commands, annual stipends, and large estates. The title used was "king" (王, wáng) but—unlike the princes in the

Like scholar-officials, military generals were ranked in a hierarchic grading system and were given merit evaluations every five years (as opposed to three years for officials).[144] However, military officers had less prestige than officials. This was due to their hereditary service (instead of solely merit-based) and Confucian values that dictated those who chose the profession of violence (wu) over the cultured pursuits of knowledge (wen).[145] Although seen as less prestigious, military officers were not excluded from taking civil service examinations, and after 1478 the military even held their own examinations to test military skills.[146] In addition to taking over the established bureaucratic structure from the Yuan period, the Ming emperors established the new post of the travelling military inspector. In the early half of the dynasty, men of noble lineage dominated the higher ranks of military office; this trend was reversed during the latter half of the dynasty as men from more humble origins eventually displaced them.[147]

Society and culture

Literature and arts

Informal essay and travel writing was another highlight. Xu Xiake (1587–1641), a travel literature author, published his Travel Diaries in 404,000 written characters, with information on everything from local geography to mineralogy.[151][152] The first reference to the publishing of private newspapers in Beijing was in 1582; by 1638 the Peking Gazette switched from using woodblock print to movable type printing.[153] The new literary field of the moral guide to business ethics was developed during the late Ming period, for the readership of the merchant class.[154]

In contrast to Xu Xiake, who focused on technical aspects in his travel literature, the Chinese poet and official Yuan Hongdao (1568–1610) used travel literature to express his desires for individualism as well as autonomy from and frustration with Confucian court politics.[155] Yuan desired to free himself from the ethical compromises that were inseparable from the career of a scholar-official. This anti-official sentiment in Yuan's travel literature and poetry was actually following in the tradition of the Song dynasty poet and official Su Shi (1037–1101).[156] Yuan Hongdao and his two brothers, Yuan Zongdao (1560–1600) and Yuan Zhongdao (1570–1623), were the founders of the Gong'an School of letters.[157] This highly individualistic school of poetry and prose was criticized by the Confucian establishment for its association with intense sensual lyricism, which was also apparent in Ming vernacular novels such as the Jin Ping Mei.[157] Yet even gentry and scholar-officials were affected by the new popular romantic literature, seeking courtesans as soulmates to re-enact the heroic love stories that arranged marriages often could not provide or accommodate.[158]

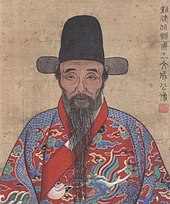

Famous painters included Ni Zan and Dong Qichang, as well as the Four Masters of the Ming dynasty, Shen Zhou, Tang Yin, Wen Zhengming, and Qiu Ying. They drew upon the techniques, styles, and complexity in painting achieved by their Song and Yuan predecessors, but added techniques and styles. Well-known Ming artists could make a living simply by painting due to the high prices they demanded for their artworks and the great demand by the highly cultured community to collect precious works of art. The artist Qiu Ying was once paid 2.8 kg (100 oz) of silver to paint a long handscroll for the eightieth birthday celebration of the mother of a wealthy patron. Renowned artists often gathered an entourage of followers, some who were amateurs who painted while pursuing an official career and others who were full-time painters.[159]

The period was also renowned for ceramics and porcelains. The major production center for porcelain was the

Carved designs in lacquerware and designs glazed onto porcelain wares displayed intricate scenes similar in complexity to those in painting. These items could be found in the homes of the wealthy, alongside embroidered silks and wares in jade, ivory, and cloisonné. The houses of the rich were also furnished with rosewood furniture and feathery latticework. The writing materials in a scholar's private study, including elaborately carved brush holders made of stone or wood, were designed and arranged ritually to give an aesthetic appeal.[161]

Connoisseurship in the late Ming period centered on these items of refined artistic taste, which provided work for art dealers and even underground scammers who themselves made imitations and false attributions.

Religion

The dominant religious beliefs during the Ming dynasty were the various forms of

The Yongle Emperor and later emperors strongly patronised Tibetan Buddhism by supporting construction, printing of sutras, ceremonies etc., to seek legitimacy among foreign audiences. Yongle tried to portray himself as a Buddhist ideal king, a cakravartin.[166] There is evidence that this portrayal was successful in persuading foreign audiences.[167]

Islam was also well-established throughout China, with a history said to have begun with Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas during the Tang dynasty and strong official support during the Yuan. Although the Ming sharply curtailed this support, there were still several prominent Muslim figures early on, including the Yongle Emperor's powerful eunuch Zheng He. The Hongwu Emperor's generals Chang Yuqun, Lan Yu, Ding Dexing, and Mu Ying have also been identified as Muslim by Hui scholars, though this is doubted by non-Muslim sources. Regardless, the presence of Muslims in the armies that drove the Mongols northwards caused a gradual shift in the Chinese perception of Muslims, transitioning from "foreigners" to "familiar strangers".[168] The Hongwu Emperor wrote a 100 character praise of Islam and the prophet Muhammad. The Ming Emperors strongly sponsored the construction of mosques and granted generous liberties for the practice of Islam.[169]

The advent of the Ming was initially devastating to Christianity: in his first year, the

During his mission, Ricci was also contacted in Beijing by one of the approximately 5,000

Philosophy

Wang Yangming's Confucianism

During the Ming dynasty, the

Conservative reaction

Other

The liberal views of Wang Yangming were opposed by the Censorate and by the Donglin Academy, re-established in 1604. These conservatives wanted a revival of orthodox Confucian ethics. Conservatives such as Gu Xiancheng (1550–1612) argued against Wang's idea of innate moral knowledge, stating that this was simply a legitimization for unscrupulous behavior such as greedy pursuits and personal gain. These two strands of Confucian thought, hardened by Chinese scholars' notions of obligation towards their mentors, developed into pervasive factionalism among the ministers of state, who used any opportunity to impeach members of the other faction from court.[182]

Urban and rural life

Wang Gen was able to give philosophical lectures to many commoners from different regions because—following the trend already apparent in the Song dynasty—communities in Ming society were becoming less isolated as the distance between market towns was shrinking. Schools, descent groups, religious associations, and other local voluntary organizations were increasing in number and allowing more contact between educated men and local villagers.

A variety of occupations could be chosen or inherited from a father's line of work. This would include – but was not limited to – coffin makers, ironworkers and blacksmiths, tailors, cooks and noodle-makers, retail merchants, tavern, teahouse, or winehouse managers, shoemakers, seal cutters, pawnshop owners, brothel heads, and merchant bankers engaging in a proto-banking system involving notes of exchange.[81][185] Virtually every town had a brothel where female and male prostitutes could be had.[186] Male catamites fetched a higher price than female concubines since pederasty with a teenage boy was seen as a mark of elite status, regardless of sodomy being repugnant to sexual norms.[187] Public bathing became much more common than in earlier periods.[188] Urban shops and retailers sold a variety of goods such as special paper money to burn at ancestral sacrifices, specialized luxury goods, headgear, fine cloth, teas, and others.[185] Smaller communities and townships too poor or scattered to support shops and artisans obtained their goods from periodic market fairs and traveling peddlers. A small township also provided a place for simple schooling, news and gossip, matchmaking, religious festivals, traveling theater groups, tax collection, and bases of famine relief distribution.[184]

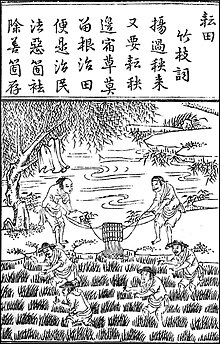

Farming villagers in the north spent their days harvesting crops like wheat and millet, while farmers south of the

Early Ming dynasty saw the strictest

Science and technology

After the flourishing of

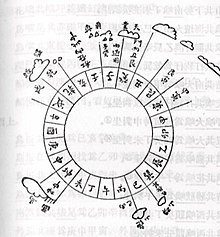

By the 16th century the Chinese calendar was in need of reform. Although the Ming had adopted Guo Shoujing's Shoushi calendar of 1281, which was just as accurate as the Gregorian calendar, the Ming Directorate of Astronomy failed to periodically readjust it;[clarification needed] this was perhaps due to their lack of expertise since their offices had become hereditary in the Ming and the Statutes of the Ming prohibited private involvement in astronomy.[197][198] A sixth-generation descendant of the Hongxi Emperor, the "Prince" Zhu Zaiyu (1536–1611), submitted a proposal to fix the calendar in 1595, but the ultra-conservative astronomical commission rejected it.[199][198] This was the same Zhu Zaiyu who discovered the system of tuning known as equal temperament, a discovery made simultaneously by Simon Stevin (1548–1620) in Europe.[200] In addition to publishing his works on music, he was able to publish his findings on the calendar in 1597.[198] A year earlier, the memorial of Xing Yunlu suggesting a calendar improvement was rejected by the Supervisor of the Astronomical Bureau due to the law banning private practice of astronomy; Xing would later serve with Xu Guangqi in reforming the calendar (Chinese: 崇禎暦書) in 1629 according to Western standards.[198]

When the Ming founder Hongwu came upon the mechanical devices housed in the Yuan dynasty's palace at Khanbaliq—such as fountains with balls dancing on their jets, self-operating tiger automata, dragon-headed devices that spouted mists of perfume, and mechanical clocks in the tradition of Yi Xing (683–727) and Su Song (1020–1101)—he associated all of them with the decadence of Mongol rule and had them destroyed.[201] This was described in full length by the Divisional Director of the Ministry of Works, Xiao Xun, who also carefully preserved details on the architecture and layout of the Yuan dynasty palace.[201] Later, European Jesuits such as Matteo Ricci and Nicolas Trigault would briefly mention indigenous Chinese clockworks that featured drive wheels.[202] However, both Ricci and Trigault were quick to point out that 16th-century European clockworks were far more advanced than the common time keeping devices in China, which they listed as water clocks, incense clocks, and "other instruments ... with wheels rotated by sand as if by water" (Chinese: 沙漏).[203] Chinese records—namely the Yuan Shi—describe the 'five-wheeled sand clock', a mechanism pioneered by Zhan Xiyuan (fl. 1360–80) which featured the scoop wheel of Su Song's earlier astronomical clock and a stationary dial face over which a pointer circulated, similar to European models of the time.[204] This sand-driven wheel clock was improved upon by Zhou Shuxue (fl. 1530–58) who added a fourth large gear wheel, changed gear ratios, and widened the orifice for collecting sand grains since he criticized the earlier model for clogging up too often.[205]

The Chinese were intrigued with European technology, but so were visiting Europeans of Chinese technology. In 1584, Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598) featured in his atlas Theatrum Orbis Terrarum the peculiar Chinese innovation of mounting masts and sails onto carriages, just like Chinese ships.[206] Gonzales de Mendoza also mentioned this a year later—noting even the designs of them on Chinese silken robes—while Gerardus Mercator (1512–1594) featured them in his atlas, John Milton (1608–1674) in one of his famous poems, and Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest (1739–1801) in the writings of his travel diary in China.[207] The encyclopedist

Focusing on agriculture in his Nongzheng Quanshu, the agronomist Xu Guangqi (1562–1633) took an interest in irrigation, fertilizers, famine relief, economic and textile crops, and empirical observation of the elements that gave insight into early understandings of chemistry.[216]

There were many advances and new designs in gunpowder weapons during the beginning of the dynasty, but by the mid to late Ming the Chinese began to frequently employ European-style artillery and firearms.

Li Shizhen (1518–1593)—one of the most renowned pharmacologists and physicians in Chinese history—belonged to the late Ming period. His Bencao Gangmu is a medical text with 1,892 entries, each entry with its own name called a gang. The mu in the title refers to the synonyms of each name.[225] Inoculation, although it can be traced to earlier Chinese folk medicine, was detailed in Chinese texts by the sixteenth century. Throughout the Ming dynasty, around fifty texts were published on the treatment of smallpox.[226] In regards to oral hygiene, the ancient Egyptians had a primitive toothbrush of a twig frayed at the end, but the Chinese were the first to invent the modern bristle toothbrush in 1498, although it used stiff pig hair.[227]

Population

Sinologist historians debate the population figures for each era in the Ming dynasty. The historian Timothy Brook notes that the Ming government census figures are dubious since fiscal obligations prompted many families to underreport the number of people in their households and many county officials to underreport the number of households in their jurisdiction.[228] Children were often underreported, especially female children, as shown by skewed population statistics throughout the Ming.[229] Even adult women were underreported;[230] for example, the Daming Prefecture in North Zhili reported a population of 378,167 males and 226,982 females in 1502.[231] The government attempted to revise the census figures using estimates of the expected average number of people in each household, but this did not solve the widespread problem of tax registration.[232] Some part of the gender imbalance may be attributed to the practice of female infanticide. The practice is well documented in China, going back over two thousand years, and it was described as "rampant" and "practiced by almost every family" by contemporary authors.[233] However, the dramatically skewed sex ratios, which many counties reported exceeding 2:1 by 1586, cannot likely be explained by infanticide alone.[230]

The number of people counted in the census of 1381 was 59,873,305; however, this number dropped significantly when the government found that some 3 million people were missing from the tax census of 1391.[235] Even though underreporting figures was made a capital crime in 1381, the need for survival pushed many to abandon the tax registration and wander from their region, where Hongwu had attempted to impose rigid immobility on the populace. The government tried to mitigate this by creating their own conservative estimate of 60,545,812 people in 1393.[234] In his Studies on the Population of China, Ho Ping-ti suggests revising the 1393 census to 65 million people, noting that large areas of North China and frontier areas were not counted in that census.[3] Brook states that the population figures gathered in the official censuses after 1393 ranged between 51 and 62 million, while the population was in fact increasing.[234] Even the Hongzhi Emperor (r. 1487–1505) remarked that the daily increase in subjects coincided with the daily dwindling amount of registered civilians and soldiers.[189] William Atwell states that around 1400 the population of China was perhaps 90 million people, citing Heijdra and Mote.[236]

Historians are now turning to local gazetteers of Ming China for clues that would show consistent growth in population.[229] Using the gazetteers, Brook estimates that the overall population under the Chenghua Emperor (r. 1464–87) was roughly 75 million,[232] despite mid-Ming census figures hovering around 62 million.[189] While prefectures across the empire in the mid-Ming period were reporting either a drop in or stagnant population size, local gazetteers reported massive amounts of incoming vagrant workers with not enough good cultivated land for them to till, so that many would become drifters, conmen, or wood-cutters that contributed to deforestation.[237] The Hongzhi and Zhengde emperors lessened the penalties against those who had fled their home region, while the Jiajing Emperor (r. 1521–67) finally had officials register migrants wherever they had moved or fled in order to bring in more revenues.[231]

Even with the Jiajing reforms to document migrant workers and merchants, by the late Ming era the government census still did not accurately reflect the enormous growth in population. Gazetteers across the empire noted this and made their own estimations of the overall population in the Ming, some guessing that it had doubled, tripled, or even grown fivefold since 1368.[238] Fairbank estimates that the population was perhaps 160 million in the late Ming dynasty,[239] while Brook estimates 175 million,[238] and Ebrey states perhaps as large as 200 million.[240] However, a great epidemic that started in Shanxi Province in 1633, ravaged the densely populated areas along the Grand Canal; a gazetteer in northern Zhejiang noted more than half the population fell ill that year and that 90% of the local populace in one area was dead by 1642.[241]

See also

- Economy of the Ming dynasty

- 1642 Yellow River flood

- Kingdom of Tungning

- List of tributaries of Imperial China

- Luchuan–Pingmian campaigns

- Manchuria under Ming rule

- Ming dynasty in Inner Asia

- Military conquests of the Ming dynasty

- Ming ceramics

- Ming emperors family tree

- Ming official headwear

- Ming poetry

- Transition from Ming to Qing

- Ye Chunji (for further information on rural economics in the Ming)

- Zheng Zhilong

Notes

- ^ Prior to proclaiming himself emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang declared himself King of Wu in Nanjing in 1364. The regime is known in historiography as the "Western Wu" (西吳).

- ^ Remnants of the Ming imperial family, whose regimes are collectively called the Southern Ming in historiography, ruled southern China until 1662. The Ming loyalist state Kingdom of Tungning on Taiwan lasted until 1683, but it was not ruled by the Zhu clan and thus usually not considered part of the Southern Ming.

- ^ The Ming loyalist regime Kingdom of Tungning on the island of Taiwan, ruled by the House of Zheng, is usually not considered part of the Southern Ming.

- ^ For the lower population estimate, see (Fairbank & Goldman 2006:128); for the higher, see (Ebrey 1999:197).

- ^ The last Ming princes to hold out were Zhu Shugui, Prince of Ningjing and Zhu Honghuan, who stayed with Koxinga's Ming loyalists in Taiwan until 1683. Zhu Shugui proclaimed that he acted in the name of the deceased Yongli Emperor.[103] The Qing eventually sent the 17 Ming princes still living in Taiwan back to mainland China where they spent the rest of their lives.[104] In 1725, the Yongzheng Emperor of the Qing dynasty bestowed the hereditary title of marquis on a descendant of the Ming imperial family, Zhu Zhilian, who received a salary from the Qing government and whose duty was to perform rituals at the Ming tombs, and was also inducted into the Eight Banners. He was posthumously promoted to Marquis of Extended Grace in 1750 by the Qianlong Emperor, and the title passed on through twelve generations of Ming descendants until the end of the Qing dynasty in 1912.

- ^ For the argument that they increased social mobility see Ho (1962).

References

Citations

- ^ Turchin, Adams & Hall (2006), p. 222

- ^ Taagepera (1997), p. 500

- ^ a b Ho (1959), pp. 8–9, 22, 259.

- ^ Frank (1998), p. 109.

- ^ Maddison (2006), p. 238.

- ^ Broadberry (2014).

- ^ Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ a b c Zhang (2008), pp. 148–175

- ^ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. 271.

- ^ Crawford (1961), p. 115–148

- ISBN 978-0-691-25040-3.

- ^ a b Gascoigne (2003), p. 150.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), pp. 190–191.

- ^ Gascoigne (2003), p. 151.

- ^ a b c Ebrey (1999), p. 191.

- ^ Naquin (2000), p. xxxiii.

- ^ Andrew & Rapp (2000), p. 25.

- ^ a b Ebrey (1999), pp. 192–193.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman (2006), p. 130.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman (2006), pp. 129–130.

- ^ Robinson (2008), pp. 365–399.

- ^ Robinson (2020), pp. 8–9.

- ^ Robinson (2019), pp. 144–146.

- ^ Robinson (2019), p. 248.

- ^ Shi (2002), p. 133.

- ^ Dillon (1999), p. 34.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 197.

- ^ Wang (2011), p. 101–144.

- ^ Tsai (2001), p. 159.

- ^ Zhang & Xiang (2002), p. 73

- ^ Wang & Nyima (1997), pp. 39–41.

- ^ History of Ming, Geography I, III; Western Territory III

- ^ a b c d Wylie (2003), p. 470.

- ^ Wang & Nyima (1997), pp. 1–40.

- ^ Norbu (2001), p. 52.

- ^ Kolmaš (1967), p. 32.

- ^ Wang & Nyima (1997), pp. 39–40.

- ^ Sperling (2003), pp. 474–75, 478.

- ^ Perdue (2000), p. 273.

- ^ Kolmaš (1967), pp. 28–29.

- ^ Langlois (1988), pp. 139, 161.

- ^ Geiss (1988), pp. 417–418.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 227.

- ^ Wang & Nyima (1997), p. 38.

- ^ Kolmaš (1967), pp. 30–31.

- ^ Goldstein (1997), p. 8.

- ^ The Ming Biographical Dictionary (1976), p. 23

- ^ Kolmaš (1967), pp. 34–35.

- ^ Goldstein (1997), pp. 6–9.

- ^ Robinson (2000), p. 527.

- ^ Atwell (2002), p. 84.

- ^ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. 272.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 194.

- ISSN 0041-977X.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman (2006), p. 137.

- ^ Wang (1998), pp. 317–327.

- ^ a b Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. 273.

- ^ Robinson (1999), p. 83.

- ^ Robinson (1999), pp. 84–85.

- ^ Robinson (1999), pp. 79, 101–08.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman (2006), p. 139.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 208.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 31.

- ^ Spence (1999), p. 16.

- ^ a b Spence (1999), p. 17.

- ISBN 9780806185026.

- ^ Swope (2011), p. 122–125.

- ^ Xie (2013), p. 118–120.

- ^ Herman (2007), p. 164, 165, 281.

- ^ Ness (1998), p. 139–140.

- ^ Tsai (1996), p. 119-120.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), pp. 194–195.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 11.

- ^ Spence (1999), pp. 17–18.

- ^ Chen (2016), p. 27–47.

- ^ Robinson (1995), p. 1–16.

- ^ Tsai (1996), excerpt.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 124.

- ^ Spence (1999), pp. 19–20.

- ^ Wills (1998), pp. 343–349.

- ^ a b c Spence (1999), p. 20.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 205.

- ^ Lane (2019).

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 206, 208.

- ^ Wills (1998), pp. 349–353.

- ^ Spence (1999), pp. 20–21.

- ^ Atwell (2005), p. 467–489.

- ^ So (2012), p. 4, 17–18, 32–34.

- ^ a b c Spence (1999), p. 21.

- ^ Spence (1999), pp. 22–24.

- ^ BBC News (2004).

- ^ The Cambridge History of China: Volume 9, The Ch'ing Empire to 1800, Part 1, by Denis C. Twitchett, John K. Fairbank, p. 29

- ^ Spence (1999), p. 27-28.

- ^ Spence (1999), pp. 24, 28.

- ^ a b Chang (2007), p. 92.

- ^ a b Spence (1999), p. 31.

- ^ Spence (1999), pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Spence (1999), p. 22.

- ^ Spence, 25.

- ^ Spence (1999), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Spence (1999), p. 33.

- ^ Dennerline (1985), p. 824–25.

- ^ Shepherd (1993), p. 469–70

- ^ Manthorpe (2008), p. 108.

- ^ Fan (2016), p. 97.

- ^ Yuan (1994), pp. 193–194.

- ^ Hartwell (1982), pp. 397–398.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 5.

- ^ a b Hucker (1958), p. 28.

- ^ Chang (2007), p. 15, footnote 42.

- ^ a b Chang (2007), p. 16.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 16.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 23.

- ^ Hucker (1958), pp. 29–30.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 30.

- ^ Hucker (1958), pp. 31–32.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 32.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 33.

- ^ Hucker (1958), pp. 33–35.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 35.

- ^ a b Hucker (1958), p. 36.

- ^ a b c d Hucker (1958), p. 24.

- ^ a b c Hucker (1958), p. 25.

- ^ Hucker (1958), pp. 11, 25.

- ^ Hucker (1958), pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Hucker (1958), p. 26.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 12.

- ^ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. 96.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), pp. 145–146.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), pp. 198–202.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 200.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 198.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. xxv.

- ^ Hucker (1958), pp. 11–14.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 199.

- ^ Hucker (1958), pp. 15–17, 26.

- ^ Elman (1991), p. 7–28.

- ^ Elman (2000), p. 380, 394, 392.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 18.

- ^ Hucker (1958), pp. 18–19.

- ^ Hucker (1958), pp. 24–25.

- ^ Mote (2003), p. 602–606.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 8.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 19.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman (2006), pp. 109–112.

- ^ Hucker (1958), pp. 19–20.

- ^ Robinson (1999), pp. 116–117.

- ^ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), pp. 104–105.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), pp. 202–203.

- ^ Plaks (1987), pp. 55–182.

- ^ Needham (1959), p. 524.

- ^ Hargett (1985), p. 69.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. xxi.

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 215–217.

- ^ Chang (2007), pp. 318–319.

- ^ Chang (2007), p. 319.

- ^ a b Chang (2007), p. 318.

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 229–231.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 201.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 206.

- ^ a b Spence (1999), p. 10.

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 224–225.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 225.

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 225–226.

- ^ a b Wang (2012), p. 11

- ISBN 978-0-674-02823-4.

- ^ Robinson (2020), pp. 203–207.

- ^ Lipman (1998), p. 38-39.

- doi:10.36816/shedet.006.08. Archived from the originalon 18 October 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Needham (1965), pp. 171–172.

- ^ Leslie (1998), p. 15.

- ^ Wong (1963), pp. 30–32.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 212.

- ^ White (1966), pp. 31–38.

- ^ Xu (2003), p. 47.

- ^ a b c Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. 282.

- ^ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. 281.

- ^ a b Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), pp. 281–282.

- ^ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. 283.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 158.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 230.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 213.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 206.

- ^ a b c Spence (1999), p. 13.

- ^ a b Spence (1999), pp. 12–13.

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 229, 232.

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 232–223.

- ^ Schafer (1956), p. 57.

- ^ a b c Brook (1998), p. 95.

- ^ Spence (1999), p. 14.

- ^ Zhou (1990), p. 34–40.

- ^ Needham (1959), pp. 444–445.

- ^ Needham (1959), pp. 444–447.

- ^ Wong (1963), p. 31, footnote 1.

- ^ Needham (1959), p. 110.

- ^ Needham (1965), pp. 255–257.

- ^ Peterson (1986), p. 47.

- ^ a b c d Engelfriet (1998), p. 78.

- ^ Kuttner (1975), p. 166.

- ^ Kuttner (1975), pp. 166–167.

- ^ a b Needham (1965), pp. 133, 508.

- ^ Needham (1965), p. 438.

- ^ Needham (1965), p. 509.

- ^ Needham (1965), p. 511.

- ^ Needham (1965), pp. 510–511.

- ^ Needham (1965), p. 276.

- ^ Needham (1965), pp. 274–276.

- ^ Song (1966), pp. 7–30, 84–103.

- ^ Song (1966), pp. 171–72, 189, 196.

- ^ Needham (1971), p. 668.

- ^ Needham (1971), pp. 634, 649–50, 668–69.

- ^ Song (1966), pp. 36–36.

- ^ Song (1966), pp. 237, 190.

- ^ Needham (1987), p. 126.

- ^ Needham (1987), pp. 205, 339ff.

- ^ Needham (1984), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Needham (1987), p. 372.

- ^ Needham (1987), pp. 24–25.

- ^ Needham (1987), p. 264.

- ^ Needham (1987), pp. 203–205.

- ^ Needham (1987), p. 205.

- ^ Needham (1987), pp. 498–502.

- ^ Needham (1987), p. 508.

- ^ Needham (1987), p. 229.

- ^ Yaniv & Bachrach (2005), p. 37

- ^ Hopkins (2002), p. 110: "Inoculation had been a popular folk practice ... in all, some fifty texts on the treatment of smallpox are known to have been published in China during the Ming dynasty."

- ^ The Library of Congress (2007).

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 27.

- ^ a b Brook (1998), p. 267.

- ^ a b Brook (1998), pp. 97–99.

- ^ a b Brook (1998), p. 97.

- ^ a b Brook (1998), pp. 28, 267.

- ^ Kinney (1995), p. 200–01.

- ^ a b c Brook (1998), p. 28.

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 27–28.

- ^ Atwell (2002), p. 86.

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 94–96.

- ^ a b Brook (1998), p. 162.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman (2006), p. 128.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 195.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 163.

Works cited

- Andrew, Anita N.; Rapp, John A. (2000), Autocracy and China's Rebel Founding Emperors: Comparing Chairman Mao and Ming Taizu, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-8476-9580-5.

- Atwell, William S. (2002), "Time, Money, and the Weather: Ming China and the 'Great Depression' of the Mid-Fifteenth Century", The Journal of Asian Studies, 61 (1): 83–113, JSTOR 2700190.

- ——— (2005). "Another Look at Silver Imports into China, ca. 1635–1644". Journal of World History. 16 (4): 467–489. S2CID 162090282.

- Broadberry, Stephen (2014). "China, Europe and the Great Divergence: a Study in National Accounting, 980–1850" (PDF). Economic History Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Brook, Timothy (1998), ISBN 978-0-520-22154-3.

- Chang, Michael G. (2007), A Court on Horseback: Imperial Touring & the Construction of Qing Rule, 1680–1785, Cambridge: ISBN 978-0-674-02454-0.

- Chen, Gilbert (2 July 2016). "Castration and Connection: Kinship Organization among Ming Eunuchs". Ming Studies. 2016 (74): 27–47. S2CID 152169027.

- Crawford, Robert B. (1961). "Eunuch Power in the Ming Dynasty". T'oung Pao. 49 (3): 115–148. JSTOR 4527509.

- "Definition of Ming". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Dennerline, Jerry P. (1985). "The Southern Ming, 1644–1662. By Lynn A. Struve". The Journal of Asian Studies. 44 (4): 824–825. S2CID 162510092.

- Dillon, Michael (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1026-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006), East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, ISBN 978-0-618-13384-0.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-66991-7.

- Elman, Benjamin A. (1991). "Political, Social, and Cultural Reproduction via Civil Service Examinations in Late Imperial China" (PDF). The Journal of Asian Studies. 50 (1): 7–28. (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022.

- ——— (2000). A Cultural History of Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92147-4.

- Engelfriet, Peter M. (1998), Euclid in China: The Genesis of the First Translation of Euclid's Elements in 1607 & Its Reception Up to 1723, Leiden: ISBN 978-90-04-10944-5.

- Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006), China: A New History (2nd ed.), Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01828-0.

- Fan, C. Simon (2016). Culture, Institution, and Development in China: The economics of national character. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-24183-6.

- Farmer, Edward L., ed. (1995). Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10391-0.

- Frank, Andre Gunder (1998). ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age. Berkeley; London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21129-2.

- Gascoigne, Bamber (2003), The Dynasties of China: A History, New York: Carroll & Graf, ISBN 978-0-7867-1219-9.

- Geiss, James (1988), "The Cheng-te reign, 1506–1521", in Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 403–439, ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1997), The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet and the Dalai Lama, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-21951-9.

- Hargett, James M. (1985), "Some Preliminary Remarks on the Travel Records of the Song Dynasty (960–1279)", Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews, 7 (1/2): 67–93, JSTOR 495194.

- Hartwell, Robert M. (1982), "Demographic, Political, and Social Transformations of China, 750–1550", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 42 (2): 365–442, JSTOR 2718941.

- Herman, John E. (2007). Amid the Clouds and Mist: China's Colonization of Guizhou, 1200–1700 (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-02591-2.

- Ho, Ping-ti (1959), Studies on the Population of China: 1368–1953, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-85245-7.

- ——— (1962). The Ladder of Success in Imperial China. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-89496-8.

- Hopkins, Donald R. (2002). The Greatest Killer: Smallpox in History. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-35168-1.

- Hucker, Charles O. (1958), "Governmental Organization of The Ming Dynasty", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 21: 1–66, JSTOR 2718619.

- Jiang, Yonglin (2011). The Mandate of Heaven and The Great Ming Code. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80166-7.

- Kinney, Anne Behnke (1995). Chinese Views of Childhood. University of Hawai'i Press. JSTOR j.ctt6wr0q3.

- Kolmaš, Josef (1967), Tibet and Imperial China: A Survey of Sino-Tibetan Relations Up to the End of the Manchu Dynasty in 1912: Occasional Paper 7, Canberra: The Australian National University, Centre of Oriental Studies.

- Kuttner, Fritz A. (1975), "Prince Chu Tsai-Yü's Life and Work: A Re-Evaluation of His Contribution to Equal Temperament Theory" (PDF), Ethnomusicology, 19 (2): 163–206, S2CID 160016226, archived from the original(PDF) on 26 February 2020.

- Langlois, John D. Jr. (1988), "The Hung-wu reign, 1368–1398", in Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 107–181, ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Lane, Kris (30 July 2019). "Potosí: the mountain of silver that was the first global city". Aeon. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- Leslie, Donald D. (1998). "The Integration of Religious Minorities in China: The Case of Chinese Muslims" (PDF). www.islamicpopulation.com. The 59th George E. Morrison Lecture in Ethnology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- Lipman, Jonathan N. (1998), Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China, Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Maddison, Angus (2006). Development Centre Studies The World Economy Volume 1: A Millennial Perspective and Volume 2: Historical Statistics. Paris: OECD Publishing. ISBN 978-92-64-02262-1.

- Manthorpe, Jonathan (2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-230-61424-6.

- Naquin, Susan (2000). Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400–1900. Berkeley: University of California press. p. xxxiii. ISBN 978-0-520-21991-5.

- Bibcode:1959scc3.book.....N.

- ——— (1965), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering, Cambridge University Press.

- ——— (1971), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics, Cambridge University Press.

- ——— (1984), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 2: Agriculture, Cambridge University Press.

- ——— (1987), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press.

- Ness, John Philip (1998). The Southwestern Frontier During the Ming Dynasty (PhD thesis). University of Minnesota.

- Norbu, Dawa (2001), China's Tibet Policy, Richmond: Curzon, ISBN 978-0-7007-0474-3.

- Perdue, Peter C. (2000), "Culture, History, and Imperial Chinese Strategy: Legacies of the Qing Conquests", in van de Ven, Hans (ed.), Warfare in Chinese History, Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, pp. 252–287, ISBN 978-90-04-11774-7.

- Peterson, Willard J. (1986). "Calendar Reform Prior to the Arrival of Missionaries at the Ming Court". Ming Studies. 1986 (1): 45–61. .

- JSTOR j.ctt17t75h5.

- Robinson, David M. (1995). "Notes on Eunuchs in Hebei During the Mid-Ming Period". Ming Studies. 1995 (1): 1–16. .

- ——— (1999), "Politics, Force and Ethnicity in Ming China: Mongols and the Abortive Coup of 1461", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 59 (1): 79–123, JSTOR 2652684.

- ——— (2000), "Banditry and the Subversion of State Authority in China: The Capital Region during the Middle Ming Period (1450–1525)", Journal of Social History, 33 (3): 527–563, S2CID 144496554.

- ——— (2008), "The Ming court and the legacy of the Yuan Mongols" (PDF), in Robinson, David M. (ed.), Culture, Courtiers, and Competition: The Ming Court (1368–1644), Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 365–421, ISBN 978-0-674-02823-4, archived from the original(PDF) on 11 June 2016, retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ——— (2019). In the Shadow of the Mongol Empire: Ming China and Eurasia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10-868279-4.

- ——— (2020). Ming China and its Allies: Imperial Rule in Eurasia (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-1-108-48922-5.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1956), "The Development of Bathing Customs in Ancient and Medieval China and the History of the Floriate Clear Palace", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 76 (2): 57–82, JSTOR 595074.

- Shepherd, John Robert (1993). Statecraft and Political Economy on the Taiwan Frontier, 1600–1800. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2066-3.

- Shi, Zhiyu (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Routledge studies – China in transition. Vol. 13 (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-28372-4.

- So, Billy Kee Long (2012). The Economy of Lower Yangzi Delta in Late Imperial China: Connecting Money, Markets, and Institutions. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-50896-4.

- Song, Yingxing (1966), T'ien-Kung K'ai-Wu: Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century, translated with preface by E-Tu Zen Sun and Shiou-Chuan Sun, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- ISBN 978-0-393-97351-8.

- Sperling, Elliot (2003), "The 5th Karma-pa and some aspects of the relationship between Tibet and the Early Ming", in McKay, Alex (ed.), The History of Tibet: Volume 2, The Medieval Period: c. AD 850–1895, the Development of Buddhist Paramountcy, New York: Routledge, pp. 473–482, ISBN 978-0-415-30843-4.

- Swope, Kenneth M. (2011). "6 To catch a tiger The Eupression of the Yang Yinglong Miao uprising (1578–1600) as a case study in Ming military and borderlands history". In Aung-Thwin, Michael Arthur; Hall, Kenneth R. (eds.). New Perspectives on the History and Historiography of Southeast Asia: Continuing Explorations. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-81964-3.

- JSTOR 2600793.

- The Great Ming Code / Da Ming lu. University of Washington Press. 2012. ISBN 978-0-295-80400-2.

- Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (1996). The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2687-6.

- ——— (2001). Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80022-6.

- "Tsunami among world's worst disasters". BBC News. 30 December 2004. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2). Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Wang, Gungwu (1998), "Ming Foreign Relations: Southeast Asia", in Twitchett, Denis; Mote, Frederick W. (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 2, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 301–332, ISBN 978-0-521-24333-9.

- Wang, Jiawei; Nyima, Gyaincain (1997), The Historical Status of China's Tibet, Beijing: China Intercontinental Press, ISBN 978-7-80113-304-5.

- Wang, Yuan-kang (2011). "The Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)". Harmony and War: Confucian Culture and Chinese Power Politics. Columbia University Press. JSTOR 10.7312/wang15140.

- Wang, Richard G. (2012). The Ming Prince and Daoism: Institutional Patronage of an Elite. OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-976768-7.

- White, William Charles (1966), The Chinese Jews, Volume 1, New York: Paragon Book Reprint Corporation.

- "Who invented the toothbrush and when was it invented?". The Library of Congress. 4 April 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- Wills, John E. Jr. (1998), "Relations with Maritime Europe, 1514–1662", in Twitchett, Denis; Mote, Frederick W. (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 2, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 333–375, ISBN 978-0-521-24333-9.

- Wong, H.C. (1963), "China's Opposition to Western Science during Late Ming and Early Ch'ing", Isis, 54 (1): 29–49, S2CID 144136313.

- Wylie, Turrell V. (2003), "Lama Tribute in the Ming Dynasty", in McKay, Alex (ed.), The History of Tibet: Volume 2, The Medieval Period: c. AD 850–1895, the Development of Buddhist Paramountcy, New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-30843-4.

- Xie, Xiaohui (2013). "5 From Woman's Fertility to Masculine Authority: The Story of the White Emperor Heavenly Kings in Western Hunan". In Faure, David; Ho, Ts'ui-p'ing (eds.). Chieftains into Ancestors: Imperial Expansion and Indigenous Society in Southwest China (illustrated ed.). UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-2371-5.

- Xu, Xin (2003). The Jews of Kaifeng, China : history, culture, and religion. Jersey City, NJ: KTAV Publishing House. ISBN 978-0-88125-791-5.

- Yaniv, Zohara; Bachrach, Uriel (2005). Handbook of Medicinal Plants. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-56022-995-7.

- Yuan, Zheng (1994), "Local Government Schools in Sung China: A Reassessment", History of Education Quarterly, 34 (2): 193–213, S2CID 144538656.

- Zhang Tingyu; et al. (1739). (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Zhang, Wenxian (2008). "The Yellow Register Archives of Imperial Ming China". Libraries & the Cultural Record. 43 (2): 148–175. S2CID 201773710.

- Zhang, Yuxin; Xiang, Hongjia (2002). Testimony of History. China: China Intercontinental Press. ISBN 978-7-80113-885-9.

- Zhou, Shao Quan (1990). "明代服饰探论" [On the Costumes of Ming Dynasty]. 史学月刊 (in Chinese) (6): 34–40.

Further reading

Reference works and primary sources

- Farmer, Edward L. ed. Ming History: An Introductory Guide to Research (1994).

- Goodrich, Luther Carrington (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368–1644. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-03833-1.

- The Ming History English Translation Project, A collaborative project that makes available translations (from Chinese to English) of portions of the 明史 Mingshi (Official History of the Ming Dynasty).

- Lynn Struve, The Ming-Qing conflict, 1619–1683: A historiography and source guide, Online Indiana University.

General studies

- Brook, Timothy. The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties (History of Imperial China) (Harvard UP, 2010). excerpt

- Chan, Hok-Lam (1988), "The Chien-wen, Yung-lo, Hung-shi, and Hsuan-te reigns, 1399–1435", in Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 182–384, ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Dardess, John W. (1983), Confucianism and Autocracy: Professional Elites in the Founding of the Ming Dynasty, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-04733-4.

- Dardess, John W. (1968), Background Factors in the Rise of the Ming Dynasty, Columbia University.

- Dardess, John W. (2012), Ming China, 1368–1644: A Concise History of a Resilient Empire, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-1-4422-0491-1.

- Dardess, John W. A Ming Society: T'ai-ho County, Kiangsi, in the Fourteenth to Seventeenth Centuries (U of California Press, 1996) online free

- ISBN 978-0-300-02518-7.

- Mote, Frederick W. (1988), "The Ch'eng-hua and Hung-chih reigns, 1465–1505", in Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge UP, pp. 343–402, ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- Mote, Frederick W. (2003). Imperial China, 900–1800. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- Owen, Stephen (1997), "The Yuan and Ming Dynasties", in Owen, Stephen (ed.), An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911, New York: ).

- Swope, Kenneth M. "Manifesting Awe: Grand Strategy and Imperial Leadership in the Ming Dynasty." Journal of Military History 79.3 (2015). pp. 597–634.

- Wade, Geoff (2008), "Engaging the South: Ming China and Southeast Asia in the Fifteenth Century", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 51 (4): 578–638, JSTOR 25165269.

- ISBN 0-521-36518-X.

External links

- Notable Ming dynasty painters and galleries at China Online Museum

- Ming dynasty art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Highlights from the British Museum exhibition Archived 20 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine