Minotaur

In

Etymology

The word "Minotaur" derives from the

"Minotaur" was originally a proper noun in reference to this mythic figure. That is, there was only the one Minotaur. In contrast, the use of "minotaur" as a common noun to refer to members of a generic "species" of bull-headed creatures developed much later, in 20th century fantasy genre fiction.

The Minotaur was called Θevrumineš in Etruscan.[11]

English pronunciation of the word "Minotaur" is varied. The following can be found in dictionaries: /ˈmaɪnətɔːr, -noʊ-/ MY-nə-tor, -noh-,[1] /ˈmɪnətɑːr, ˈmɪnoʊ-/ MIN-ə-tar, MIN-oh-,[2] /ˈmɪnətɔːr, ˈmɪnoʊ-/ MIN-ə-tor, MIN-oh-.[12]

Creation myth

After ascending the throne of the island of Crete, Minos competed with his brothers as ruler. Minos prayed to the sea god Poseidon to send him a snow-white bull as a sign of the god's favour. Minos was to sacrifice the bull to honor Poseidon, but owing to the bull's beauty he decided instead to keep him. Minos believed that the god would accept a substitute sacrifice. To punish Minos, Poseidon made Minos's wife Pasiphaë fall in love with the bull. Pasiphaë had the craftsman Daedalus fashion a hollow wooden cow, which she climbed into to mate with the bull. She then bore Asterius, the Minotaur.[13] Pasiphaë nursed the Minotaur but he grew in size and became ferocious. As the unnatural offspring of a woman and a beast, the Minotaur had no natural source of nourishment and thus devoured humans for sustenance.[citation needed] Minos, following advice from the oracle at Delphi, had Daedalus construct a gigantic Labyrinth to hold the Minotaur. Its location was near Minos's palace in Knossos.[14]

Appearance

The Minotaur is commonly represented in Classical art with the body of a man and the head and tail of a bull. According to Sophocles's Trachiniai, when the river spirit Achelous seduced Deianira, one of the guises he assumed was a man with the head of a bull. From classical antiquity through the Renaissance, the Minotaur appears at the center of many depictions of the Labyrinth.[15] Ovid's Latin account of the Minotaur, which did not describe which half was bull and which half man, was the most widely available during the Middle Ages, and several later versions show a man's head and torso on a bull's body – the reverse of the Classical configuration, reminiscent of a centaur.[16] This alternative tradition survived into the Renaissance, and is reflected in Dryden's elaborated translation of Virgil's description of the Minotaur in Book VI of the Aeneid: "The lower part a beast, a man above / The monument of their polluted love."[17] It still figures in some modern depictions, such as Steele Savage's illustrations for Edith Hamilton's Mythology (1942).

Theseus myth

All the stories agree that prince

In some versions he was killed by the

When the time for the third sacrifice approached, the Athenian prince Theseus volunteered to slay the Minotaur. Isocrates orates that Theseus thought that he would rather die than rule a city that paid a tribute of children's lives to their enemy.[21] He promised his father Aegeus that he would change the somber black sail of the boat carrying the victims from Athens to Crete, and put up a white sail for his return journey if he was successful; the crew would leave up the black sail if he was killed.

In Crete, Minos's daughter

Interpretations

The contest between Theseus and the Minotaur was frequently represented in

Pasiphaë gave birth to Asterius, who was called the Minotaur. He had the face of a bull, but the rest of him was human; and Minos, in compliance with certain oracles, shut him up and guarded him in the Labyrinth.[23]

While the ruins of Minos's palace at Knossos were discovered, the Labyrinth never was. The multiplicity of rooms, staircases and corridors in the palace has led some archaeologists to suggest that the palace itself was the source of the Labyrinth myth, with over 1300 maze-like compartments,[24] an idea that is now generally discredited.[d]

Homer, describing the shield of Achilles, remarked that Daedalus had constructed a ceremonial dancing ground for Ariadne, but does not associate this with the term labyrinth.

Some 19th century mythologists proposed that the Minotaur was a personification of the sun and a Minoan adaptation of the Baal-Moloch of the Phoenicians. The slaying of the Minotaur by Theseus in that case could be interpreted as a memory of Athens breaking tributary relations with Minoan Crete.[26]

According to

A geological interpretation also exists. Citing early descriptions of the minotaur by Callimachus as being entirely focused on the "cruel bellowing"[31][e] it made from its underground labyrinth, and the extensive tectonic activity in the region, science journalist Matt Kaplan has theorised that the myth may well stem from geology. [f]

Image gallery

-

Theseus and the Minotaur, Attic black-figure kylix tondo, c. 450–440 BC.

-

Theseus and the Minotaur. Detail from an Attic black-figure amphora, c. 575 BC–550 BC.

-

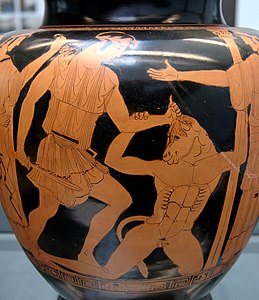

Theseus and the Minotaur. Side A from an Attic red-figure stamnos, c. 460 BC.

-

Theseus and the Minotaur. Side A from a black-figure Attic amphora, c. 540 BC.

-

Tondo of the Aison Cup, showing the victory of Theseus over the Minotaur in the presence of Athena.

-

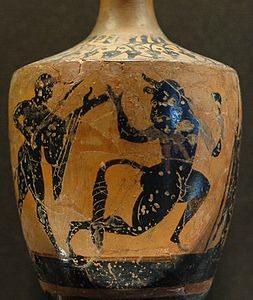

Theseus and the Minotaur. Attic black-figure lekythos, 500–475 BC. From Crimea.

-

Theseus and the Minotaur. Attic red-figured plate, 520–510 BC.

-

Theseus and the Minotaur

-

Theseus and the Minotaur

-

Theseus and the Minotaur

References in media

Dante's Inferno

The Minotaur (infamia di Creti, Italian for 'infamy of Crete'), appears briefly in

Lo savio mio inver' lui gridò: "Forse |

My sage cried out to him: "You think, |

| —Inferno, Canto XII, lines 16–20 |

In these lines, Virgil taunts the Minotaur to distract him, and reminds the Minotaur that he was killed by

Giovanni Boccaccio writes of the Minotaur in his literary commentary of the Commedia: "When he had grown up and become a most ferocious animal, and of incredible strength, they tell that Minos had him shut up in a prison called the labyrinth, and that he had sent to him there all those whom he wanted to die a cruel death".[38] Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in his own commentary,[39][40] compares the Minotaur with all three sins of violence within the seventh circle: "The Minotaur, who is situated at the rim of the tripartite circle, fed, according to the poem was biting himself (violence against one's body) and was conceived in the 'false cow' (violence against nature, daughter of God)."

Virgil and Dante then pass quickly by to the centaurs (Nessus, Chiron and Pholus) who guard the Flegetonte ("river of blood"), to continue through the seventh Circle.[41]

Surrealist art

- Pablo Picasso made a series of etchings in the Vollard Suite showing the Minotaur being tormented, possibly inspired also by Spanish bullfighting.[42]

Television, literature and plays

- Argentine author Julio Cortázar published the play Los reyes (The Kings) in 1949, which reinterprets the Minotaur's story. In the book, Ariadne is not in love with Theseus, but with her brother the Minotaur.[43]

- The short story The House of Asterion by the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges gives the Minotaur's story from the monster's perspective.

- Asterion, depicted as a human prince who wears a bull mask, is the chief antagonist of The King Must Die, Mary Renault's 1958 reinterpretation of the Theseus myth in the light of the excavation of Knossos.

- Aleksey Ryabinin's book Theseus (2018).[44][45] provides a retelling of the myths of Theseus, Minotaur, Ariadne and other personages of Greek mythology.

- In the horror novel House of Leaves (2000) by author Mark Z. Danielewski the myth of the Minotaur is retold from the perspective of King Minos and functions as a recurring theme. Additionally the legend serves as a parallel to the labyrith-like architecture of The House on Ash Tree Lane, which is the main subject of the book.

- The historical fiction novel Once a Monster by Robert Dinsdale is a continuation of the myth of the Minotaur, if he had survived Theseus's attempt to kill him.[46][47]

Film

- Minotaur, the Wild Beast of Crete, a 1960 Italian film directed by Silvio Amadio and starring Bob Mathias[48]

- Lions Gate in 2006.[49]

- The Minotaur appears in Wrath of the Titans as a minor antagonist, played by Spencer Wilding.[50]

- Natalie Portman and Danny McBride fight a minotaur while reclaiming a magical sword from a labyrinth in Your Highness, released in 2011 by Universal Pictures.[51]

Video games

- In the 2013 video game Shin Megami Tensei IV, the Minotaur appears as a boss fight at the end of the game's first dungeon, Naraku.

- In the 2020 video game Ultrakill, the Minotaur appears as a boss fight at the end of the first level in the Violence layer.

- In the 2024 video game Sovereign Syndicate, one of the playable main characters is a minotaur.[52][53]

Museum Exhibitions

- The Minotaur and Knossos featured in the 2023 exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford, "Labyrinth: Knossos, Myth & Reality"

See also

- Theseus and the Minotaur – a logic game that is inspired by the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur in the Labyrinth.

- Kao (bull) – a legendary chaotic bull in Meitei mythology, similar to Minotaur in character

- Ox-Head and Horse-Face – two guardians or types of guardians of the underworld in Chinese mythology

- Satyr – a legendary human-horse (later human-goat) hybrid(s)

- Shedu– a figure in Mesopotamian mythology with the body of a bull and a human head

- Minotauria – a genus of woodlouse hunting spiders endemic to the Balkans[54]

Footnotes

- ^

According to Ovid:

- semibovemque virum semivirumque bovem,[5] one of the three lines that his friends would have deleted from his work, and one of the three that he, selecting independently, would preserve at all cost, in the apocryphal anecdote told by Albinovanus Pedo.[6]

- ^ In a counter-intuitive cultural development going back at least to Cretan coins of the 4th century BCE, many visual patterns representing the Labyrinth do not have dead ends like a maze; instead, a single path winds to the center.[8]

- ^

Hesiod[10] says of Zeus' establishment of Europa in Crete:

- "... he made her live with Rhadamanthys."[10]

- "... he made her live with

- ^ Sir Arthur Evans, the first of many archaeologists who have worked at Knossos, is often given credit for this idea, but he did not believe it;[25] modern scholarship generally discounts the idea.[4](pp 42–43)[7](p 25)

- ^ Callimachus first refers to the minotaur with the phrase

- ^

Kaplan argues that the minotaur is the result of ancient people trying to explain earthquakes;tectonically very active during the years when the minotaur myth first appeared.[33]Given this, he argues that the Minoans used the monster to help explain the terrifying earthquakes that were "bellowing" beneath their feet.

- ^

The City of Dis's defensive ramparts.[36]

References

- ^ a b "English Dictionary: Definition of Minotaur". Collins. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ a b Bechtel, John Hendricks (1908), Pronunciation: Designed for Use in Schools and Colleges and Adapted to the Wants of All Persons who Wish to Pronounce According to the Highest Standards, Penn Publishing Co.

- ^ Garnett, Richard; Vallée, Léon; Brandl, Alois (1923), The Book of Literature: A Comprehensive Anthology of the Best Literature, Ancient, Mediæval and Modern, with Biographical and Explanatory Notes, vol. 33, Grolier society.

- ^ ISBN 379132144-7.

- ^ Ovid. Ars Amatoria. 2.24.

- JSTOR 294479.

- ^ ISBN 978-080142393-2.

- ^ Kern (2000);[4](Chapter 1) Doob (1990)[7](Chapter 2)

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. 2.31.1.

- ^ a b Hesiod. Catalogue of Women. fr. 140.

- ^ de Simone, C. (1970). "Zu einem Beitrag über etruskisch θevru mines". Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung. 84: 221–223.

- ^ "Minotaur". American English Dictionary. Collins. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ "Apollodorus, Library, book 3, chapter 1". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 555.

- ^ Several examples are shown in Kern (2000).[4]

- ^ Examples include illustrations 204, 237, 238, and 371 in Kern.[4]

- ^ The Aeneid of Virgil, as translated by John Dryden, found at http://classics.mit.edu/Virgil/aeneid.6.vi.html . Virgil's text calls the Minotaur "biformis"; like Ovid, he does not describe which part is bull, which part man.

- ^ "Pausanias, Description of Greece, Attica, chapter 27". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ Catullus. Carmen 64.

- Servius. On the Aeneid. 6.14.

singulis quibusque annis 'every one year'.

- The annual period is given by Zimmerman, J.E. (1964). "Androgeus". Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Harper & Row; and Rose, H.J. (1959). A Handbook of Greek Mythology. Dutton. p. 265. Zimmerman cites Virgil, Apollodorus, and Pausanias.

- The annual period is given by Zimmerman, J.E. (1964). "Androgeus". Dictionary of Classical Mythology.

- ^ "Isocrates, Helen, section 27". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ Plutarch. Theseus. 15–19.Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca historica. i.16, iv.61.Apollodorus. Bibliotheke. iii.1, 15.

- ^ Apollodorus. Bibliotheca. 3.1.4.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (2007). Cope, Julian (ed.). "Knossos fieldnotes". The Modern Antiquarian.

- ^ McCullough, David (2004). The Unending Mystery. Pantheon. pp. 34–36.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 555.

- ^ Paolo Alessandro Maffei (1709), Gemmae Antiche, Pt. IV, pl. 31; Kern (2000): Maffei "erroneously deemed the piece to be from Classical antiquity".[4](p 202, fig. 371)

- ^ Kerenyi, Karl (1951). The Gods of the Greeks. p. 269.

- ^ See illustrations of Carme, for an example of a goddess crowned with a labyrinthine wreath of grain.

- ^ Kerényi, Karl (1976). Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life. pp. 104–105, 159.

- ^ a b Callimachus (1921). Callimachus, Hymns and Epigrams. Translated by Mair, A.W.; Mair, G.R. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Kaplan, Matt (2012). Science of Monsters. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- .

- ^ The traverse of this circle is a long one, filling Cantos 12 to 17.

- ^ Inferno XII, verse translation by R. Hollander, p. 228 commentary

- ^ Alighieri, Dante. "Canto IX". Inferno.

- ^ Boccaccio, Comedia delle ninfe fiorentine commentary

- ^ Boccaccio, G. (30 November 2009). Boccaccio's Expositions on Dante's Comedy. University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Bennett, Pre-Raphaelite Circle, 177–180.

- ^ "Dante Gabriel Rossetti. His Family-Letters with a Memoir (Volume Two)". www.rossettiarchive.org.

- ^ Beck, Christopher, "Justice among the Centaurs", Forum Italcium 18 (1984): 217–229

- ISBN 0269026576

- ISSN 1989-1709.

- ISBN 978-5-6040037-6-3.

- ^ O.Zdanov. Life and adventures of Theseus. // «KP», 14 February 2018.

- ^ "Book Review: 'Once A Monster' by Robert Dinsdale". Plato's Fire. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ "Once a Monster by Robert Dinsdale". www.panmacmillan.com. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ "The Minotaur, the Wild Beast of Crete". Letter Box. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Jonathan English (director). Minotaur (2005). Retrieved 2 March 2018 – via AllMovie.

- ^ "Wrath of the Titans". IMDB. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ Your Highness. AllMovie. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Macgregor, Jody (11 January 2024). "Sovereign Syndicate review". PC Gamer. Future plc. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ Kobylanski, Abraham (11 January 2024). "Sovereign Syndicate Review". RPGFan. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ Kulczyński, W. (1903). "Aranearum et Opilionum species in insula Creta a comite Dre Carolo Attems collectae". Bulletin International de l'Académie des Sciences de Cracovie. 1903: 32–58.

External links

- Minotaur in Greek Myth source Greek texts and art.