Monarchy in New Brunswick

| King in Right of New Brunswick | |

|---|---|

Provincial | |

| |

| Incumbent | |

| |

| Charles III King of Canada since 8 September 2022 | |

| Details | |

| Style | His Majesty |

| First monarch | Victoria |

| Formation | 1 July 1867 |

By the arrangements of the

Constitutional role

The role of the Crown is both legal and practical; it functions in

This arrangement began with the 1867 British North America Act[1] and continued an unbroken line of monarchical government extending back to the early 16th century. However, though it has a separate government headed by the King, as a province, New Brunswick is not itself a kingdom.[11]

Royal associations

Those in the royal family perform ceremonial duties when on a tour of the province; the royal persons do not receive any personal income for their service, only the costs associated with the exercise of these obligations are funded by both the Canadian and New Brunswick Crowns in their respective councils.[13] Monuments around New Brunswick mark some of those visits, while others honour a royal personage or event. Further, New Brunswick's monarchical status is illustrated by royal names applied to regions, communities, schools, and buildings, many of which may also have a specific history with a member or members of the royal family; New Brunswick itself is named in honour of King George III, who belonged to the House of Brunswick. Gifts are also sometimes offered from the people of New Brunswick to the royal person to mark a visit or an important milestone; for instance, Queen Elizabeth II was given in 1951 a pair of hand-woven car blankets made by the loom crofters of Gagetown and,[14] in 1976, a quilt hand-sewn by the Havelock United Baptist Church Ladies' Auxiliary.[15]

Associations also exist between the Crown and many private organizations within the province; these may have been founded by a royal charter, received a royal prefix, and/or been honoured with the patronage of a member of the royal family. Examples include the Royal Kennebeccasis Yacht Club, which received its royal prefix from Queen Victoria in 1898. At the various levels of education within New Brunswick, there also exist a number of scholarships and academic awards either established by or named for members of the royal family, such as the Queen Elizabeth II Scholarship, set up by the government of New Brunswick to coincide with the visit of the Queen to the province in 1959.[16]

The main symbol of the monarchy is the sovereign himself, his image (in portrait or effigy) thus being used to signify government authority.

History

Origin of the Crown in New Brunswick

The modern Crown's place in New Brunswick is a result of

One of George III's sons, Prince Edward, arrived in Nova Scotia, in 1794, after three years living in Quebec City. Though he resided in Halifax, the Prince acted as commander-in-chief of both Nova Scotia and New Brunswick[20] and travelled throughout, visiting Fredericton and Saint John (including Fort Howe), along the way meeting with the colony's inhabitants and first lieutenant governor, Colonel Thomas Carleton.[21] The Prince set up a semapore telegraph system between the two colonial capitals, Halifax and Fredericton.[21]

The first royal tours

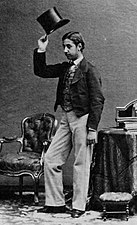

Edward's grandson, Prince Albert Edward (later King Edward VII), toured New Brunswick in 1860, as part of his five-month journey around the Canadas. The Prince's arrival in Fredericton, aboard the steamboat Forest Queen, on 4 August, was regarded as the "social event of the year". Among other duties, the Prince attended a reception and officially opened Wilmot Park.[22][23]

While strolling the grounds of

After the First World War

Edward VII's grandson, Prince Edward (later King Edward VIII), toured New Brunswick in 1919.

After the Second World War

King

Only a few months later, Princess Elizabeth acceded as Queen of Canada. Services of thanksgiving were held across the province for

The 1970s

Fredericton was again the starting point of a provincial tour by the Queen and Prince Philip, on 15 July 1976. Lieutenant Governor

Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, at the Boy Scout and Girl Guide jamboree at Woolastook Provincial Park, near Fredericton, 15 July 1976

|

Elizabeth and Philip stopped at the Boy Scout and Girl Guide jamboree at Woolastook Provincial Park, where they had a picnic with the approximately 3,500 scouts and guides in attendance and watched performances by the Madawaska Dancers,[37] Les jeunes chanteurs d’Acadie, the Kiwanis Steel Band, and the St. Andrew's Pipe Band,[37] before moving on to Kings Landing Historical Settlement,[38][39] there opening Morehouse House and launching the reproduction of the historical sailing ship, Brunswick Lion,[40] which greatly interested Prince Philip, given his naval background.[25] In the evening, the Queen hosted a dinner at McConnell Hall, at the University of New Brunswick,[41] followed by a fireworks show.[38]

In

The 1980s

The Queen and Prince Philip journeyed to New Brunswick to celebrate the province's bicentennial in 1984, arriving at Moncton on 24 September.

The 2000s

For the

The Queen and Duke of Edinburgh the following day, 12 October 2002, visited

In 2022, New Brunswick instituted a

See also

References

- ^ Victoria (29 March 1867), Constitution Act, 1867, III.9, V.58, Westminster: Queen's Printer, retrieved 15 January 2009

- ^ Elizabeth II (17 December 2004), An Act to Amend the Municipal Assistance Act, 4.b, Fredericton: Queen's Printer for New Brunswick, retrieved 6 July 2009

- ^ Elizabeth II (22 June 2006), Clean Air Act, 1, Fredericton: Queen's Printer for New Brunswick, retrieved 6 July 2009

- ^ Moreau‑Bérubé v. New Brunswick, Title (Supreme Court of Canada 7 February 2002), Text.

- ISBN 978-0-662-46012-1

- ^ Cox, Noel (September 2002). "Black v Chrétien: Suing a Minister of the Crown for Abuse of Power, Misfeasance in Public Office and Negligence". Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law. 9 (3). Perth: Murdoch University: 12. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-100-11096-7, archived from the originalon 24 September 2009, retrieved 17 May 2009

- ^ MacLeod 2008, p. 16.

- ^ Roberts, Edward (2009). "Ensuring Constitutional Wisdom During Unconventional Times" (PDF). Canadian Parliamentary Review. 23 (1). Ottawa: Commonwealth Parliamentary Association: 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ^ MacLeod 2008, p. 20

- ISBN 978-0-7710-9773-7

- ^ MacLeod 2008, p. XIV

- ^ Palmer, Sean; Aimers, John (2002), The Cost of Canada's Constitutional Monarchy: $1.10 per Canadian (2 ed.), Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada, archived from the original on 19 June 2008, retrieved 15 May 2009

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick (2009). "Exhibits and Education Tools > Royal Visits to New Brunswick > The Golden Jubilee: A New Brunswick Tribute > 1951 > Welcome to New Brunswick > The Official Welcome". Queen's Printer for New Brunswick. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2009, Welcome to the Miramichi

- ^ Elizabeth II (28 July 1959), "Reply to the Premier of New Brunswick", in New Brunswick Provincial Archives (ed.), The Golden Jubilee: A New Brunswick Tribute, Fredericton: Queen's Printer for New Brunswick (published 2009), PANB RS415/D10b, retrieved 4 November 2008

- ISBN 978-0-7712-1016-7

- ^ Slumkoski, Corey (2005), "The Partition of Nova Scotia", The Winslow Papers, Electronic text centre (UNB Libraries), archived from the original on 4 August 2020, retrieved 5 May 2020

- ^ Censuses of Canada 1665 to 1871: Upper Canada & Loyalists (1785 to 1797), Statistics Canada, 22 October 2008, retrieved 24 July 2013

- ^ Harris, Carolyn (3 February 2022), "Royals Who Lived in Canada", The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, retrieved 2 April 2023

- ^ a b Tidridge, Nathan, Prince Edward and New Brunswick, the Crown in Canada, retrieved 4 April 2023

- ISBN 978-1-4597-1165-5.

- ^ a b Provincial Archives of New Brunswick (2002), "The Golden Jubilee: A New Brunswick Tribute", P229-46, King's Printer for New Brunswick, retrieved 16 March 2023

- ^ Celebrating the Platinum Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (PDF), Kings Landing, 2022, p. 2, retrieved 3 April 2023

- ^ a b Platinum Jubilee Celebration, King's Landing, retrieved 2 April 2022

- ^ a b Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P155-1394

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, PC670.8-14

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, PC670.8-23

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, PC670.8-44

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, PC670.8-11

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P155-1394

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, Introduction

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P116-128

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, Welcome Your Majesty

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P194-478

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, 1

- ^ a b Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, 2

- ^ a b c Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, The 1976 Royal Visit

- ^ “At Home in Canada”: Royalty at Canada’s Historic Places, Canad's Historic Places, retrieved 30 April 2023

- ^ Kings Landing 2022, p. 3

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-18

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P194-476

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, 3

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, 4

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, Celebrating the Bicentennial

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-32

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-37

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-40

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, Home

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-38

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-43

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, The Diamond Jubilee: A Time to Reflect

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-15

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-25

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-20

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-34

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-22

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-28

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-39

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-44

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-47

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-42

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-53

- ^ Provincial Archives of New Brunswick 2002, P229-53

- ^ "The Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Medal (New Brunswick)". Government of New Brunswick. 22 April 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

Further information

- Remembering Elizabeth in New Brunswick: See treasures from the archives, CBC News, 18 September 2022