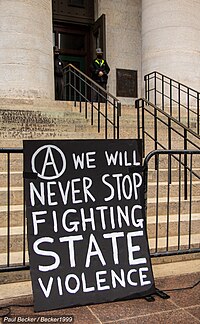

Monopoly on violence

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

In political philosophy, a monopoly on violence or monopoly on the legal use of force is the property of a polity that is the only entity in its jurisdiction to legitimately use force, and thus the supreme authority of that area.

While the monopoly on violence as the defining conception of the

Max Weber's theory

Max Weber wrote in Politics as a Vocation that a fundamental characteristic of statehood is the claim of such a monopoly. An expanded definition appears in Economy and Society:

A compulsory political organization with continuous operations will be called a 'state' [if and] insofar as its administrative staff successfully upholds a claim to the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force (das Monopol legitimen physischen Zwanges) in the enforcement of its order.[3][4]

Weber applied several caveats to this definition:

- He intended the statement as a contemporary observation, noting that the connection between the state and the use of physical force has not always been so close. He uses the examples of religious courts, which had sole jurisdiction over some types of offenses, especially heresyand sex crimes (thus the nickname "bawdy courts"). Regardless, the state exists wherever a single authority can legitimately authorize violence.

- For the same reasons, "monopoly" does not mean that only the government may use physical force, but that the state is that human community that successfully claims for itself to be the only source of legitimacy for all physical coercion or adjudication of coercion. For example, the law might permit individuals to use force in defense of one's self or property, but this right derives from the state's authority. This conflicts directly with enlightenment principles of individual sovereignty that delegates power to the state by consent, and concepts of natural law that hold that individual rights deriving from sapient self-ownership preexist the state and are only recognised and guaranteed by the state which may be restricted from limiting them by constitutional law.[5]

Criticisms of Weber

Robert Hinrichs Bates argues that the state itself has no violent power; rather, the people hold all the power of coercion to ensure that order and other equilibriums hold up.[6] The implication of this is that there is a frontier of well-being in stateless societies, that can only be surpassed if some level of coercion or violence is used to elevate the complexity of the state. In other words, without investing in troops, police, or some sort of enforcement mechanism, early states cannot enjoy the law and order (or prosperity) of more developed states.

Relation to state capacity

The capacity of a state is often measured in terms of its fiscal and legal capacity. Fiscal capacity meaning the state's ability to recover taxation, and legal capacity meaning the state's supremacy as sole arbiter of conflict resolution and contract enforcement. Without some sort of coercion, the state would not otherwise be able to enforce its legitimacy in its desired sphere of influence. In early and developing states, this role was often played by the "stationary bandit" who defended villagers from roving bandits, in the hope that the protection would incentivize villagers to invest in economic production, and the stationary bandit could eventually use its coercive power to expropriate some of that wealth.[7]

In regions where state presence is minimally felt, non-state actors can use their monopoly on violence to establish legitimacy, or maintain power.[8] For example, the Sicilian Mafia originated as a protection racket providing buyers and sellers in the black market with protection. Without this type of enforcement, market participants would not be confident enough to trust their counter-parties to honour contracts and the market would collapse.

In unorganized and underground markets, violence is used to enforce contracts in the absence of accessible legal conflict resolution.

Other

According to Raymond Aron, international relations are characterized by the absence of widely acknowledged legitimacy in the use of force between states.[15]

Martha Lizabeth Phelps takes Weber's ideas on the legitimacy of private security a step further, claiming that the use of private actors by the state remains legitimate if and only if military contractors are perceived as being controlled by the state.[16]

In the Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, & Conflict, Jon D. Wiseman points out that a state's monopoly on violence is conferred by the people of that state in exchange for protection of their person and property, which in turn grants states the ability to coerce and exploit people through, for example, taxation.[17]

See also

- Coercion

- Counter-insurgency

- Conflict resolution

- Civilian control of the military

- Definitions of terrorism

- Failed state

- Fiscal capacity

- Insurgency

- Legitimacy (political)

- Non-state actor

- Peelian principles

- Police brutality

- Police legitimacy

- Police power (United States constitutional law)

- "Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun"

- Power (social and political)

- Private army

- State-building

- Statelessness

References

- ISBN 978-1-137-37353-3.

- ISBN 978-1-137-37353-3.

- ^ Weber, Max (1978). Roth, Guenther; Wittich, Claus (eds.). Economy and Society. Berkeley: U. California P. p. 54.

- ^ Weber, Max (1980) [1921]. Winckelmann, Johannes (ed.). Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft (5 ed.). Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck. p. 29.

- ^ Monopoly on violence at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- S2CID 14970734.

- S2CID 145312307.

- ^ Gambetta, Diego (1996). The Sicilian Mafia: the business of private protection. Harvard University Press. p. 1.

- .

- ^ Tilly, Charles (1985). “War making and state making as organized crime” in Bringing the State Back In, eds P.B. Evans, D. Rueschemeyer, and T. Skocpol. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985. • Introduction and Chapt

- .

- JSTOR 1817092.

- S2CID 182194314.

- .

- ^ Raymond Aron. Paix et guerre entre les nations, Paris 1962; English: Peace and War, 1966. New edition 2003.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-12-227010-9.