Moorish architecture

Great Mosque of Córdoba, Spain (8th century); Centre: Bab Oudaya in Rabat, Morocco (late 12th century); Bottom: Court of the Lions at the Alhambra in Granada , Spain (14th century) | |

| Years active | 8th century to present day |

|---|---|

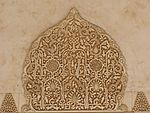

Moorish architecture is a style within Islamic architecture which developed in the western Islamic world, including al-Andalus (on the Iberian peninsula) and what is now Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia (part of the Maghreb).[1][2] Scholarly references on Islamic architecture often refer to this architectural tradition in terms such as architecture of the Islamic West[2][1][3] or architecture of the Western Islamic lands.[4][5][3] The use of the term "Moorish" comes from the historical Western European designation of the Muslim inhabitants of these regions as "Moors".[6][7][a] Some references on Islamic art and architecture consider this term to be outdated or contested.[11][12]

This architectural tradition integrated influences from pre-Islamic

This architectural style came to encompass distinctive features such as the

Even as Muslim rule ended on the Iberian Peninsula, the traditions of Moorish architecture continued in North Africa as well as in the Mudéjar style in Spain, which adapted Moorish techniques and designs for Christian patrons.[2][18] In Algeria and Tunisia local styles were subjected to Ottoman influence and other changes from the 16th century onward, while in Morocco the earlier Hispano-Maghrebi style was largely perpetuated up to modern times with fewer external influences.[2]: 243–245 In the 19th century and after, the Moorish style was frequently imitated in the form of Neo-Moorish or Moorish Revival architecture in Europe and America,[19] including Neo-Mudéjar in Spain.[20] Some scholarly references associate the term "Moorish" or "Moorish style" more narrowly with this 19th-century trend in Western architecture.[21][11]

History

Earliest Islamic monuments (8th–9th centuries)

In the 7th century the region of North Africa became steadily integrated into the emerging Muslim world during the Early Arab-Muslim Conquests. The territory of Ifriqiya (roughly present-day Tunisia), and its newly-founded capital city of Kairouan (also transliterated as "Qayrawan") became an early center of Islamic culture for the region.[22] According to tradition, the Great Mosque of Kairouan was founded here by Uqba ibn Nafi in 670, although the current structure dates from later.[1][23][2]: 28

Al-Andalus

In 711 most of the

In Seville, the Mosque of Ibn Adabbas was founded in 829 and was considered the second-oldest Muslim building in Spain (after the Great Mosque of Cordoba) until it was demolished in 1671.[b] This mosque had a hypostyle form consisting of eleven aisles divided by rows of brick arches supported on marble columns.[26][25]: 144–145 Of the brief Muslim presence in southern France during the 8th century, only a few funerary stelae have been found.[27] In 1952 French archaeologist Jean Lacam excavated the Cour de la Madeleine ('Courtyard of Madeline') in the Saint-Rustique Church in Narbonne, where he discovered remains which he interpreted as the remains of a mosque from the 8th-century Muslim occupation of Narbonne.[c][27][28]

Ifriqiya

In Ifriqiya, the

In the 9th century Ifriqiya was controlled by the

One of the most important Aghlabid monuments is the Great Mosque of Kairouan, which was completely rebuilt in 836 by the emir Ziyadat Allah I (r. 817–838), although various additions and repairs were effected later which complicate the chronology of its construction.[2]: 28–32 Its design was a major reference point in the architectural history of mosques in the Maghreb.[29]: 273 The mosque features an enormous rectangular courtyard, a large hypostyle prayer hall, and a thick three-story minaret (tower from which the call to prayer is issued). The prayer hall's layout reflects an early use of the so-called "T-plan", in which the central nave of the hypostyle hall (the one leading to the mihrab) and the transverse aisle running along the qibla wall are wider than the other aisles and intersect in front of the mihrab.[4] The mihrab of the prayer hall is among the oldest examples of its kind, richly decorated with marble panels carved in high-relief vegetal motifs and with ceramic tiles with overglaze and luster.[2]: 30 [30] Next to the mihrab is the oldest surviving minbar (pulpit) in the world, made of richly-carved teakwood panels. Both the carved panels of the minbar and the ceramic tiles of the mihrab are believed to be imports from Abbasid Iraq.[2]: 30–32 An elegant dome in front of the mihrab with an elaborately-decorated drum is one of architectural highlights of this period. Its light construction contrasts with the bulky structure of the surrounding mosque and the dome's drum is elaborately decorated with a frieze of blind arches, squinches carved in the shape of shells, and various motifs carved in low-relief.[2]: 30–32 The mosque's minaret is the oldest surviving one in North Africa and the western Islamic world.[31][32] Its form was modeled on older Roman lighthouses in North Africa, quite possibly the lighthouse at Salakta (Sullecthum) in particular.[2]: 32 [33][34]: 138

The

Western and central Maghreb

Further west, the Rustamid dynasty, who were Ibadi Kharijites and did not recognize the Abbasid Caliphs, held sway over much of the central Maghreb. Their capital, Tahart (near present-day Tiaret), was founded in the second half of the 8th century by Abd al-Rahman ibn Rustam and was occupied seasonally by its semi-nomadic inhabitants. It was destroyed by the Fatimids in 909 but its remains were excavated in the 20th century.[2]: 41 The city was surrounded by a fortified wall interspersed with square towers. It contained a hypostyle mosque, a fortified citadel on higher ground, and a palace structure with a large courtyard similar to the design of traditional houses.[2]: 41 [13]: 13–14

The

The rival caliphates (10th century)

The Caliphate of Córdoba

In the 10th century

Andalusi decoration and craftsmanship of this period became more standardized. While Classical inspirations are still present, they are interpreted more freely and are mixed with influences from the Middle East, including ancient Sasanian or more recent Abbasid motifs. This is seen for example in the stylized vegetal motifs intricately carved onto limestone panels on the walls at Madinat al-Zahra.[4]: 121–124 [6]: 103–104 It is also at Madinat al-Zahra that the "caliphal" style of horseshoe arch was formalized: the curve of the arch forms about three quarters of a circle, the voussoirs are aligned with the imposts rather than the center of the arch, the curve of the extrados is "stilted" in relation to that of the intrados, and the arch is set within a decorative alfiz.[24]: 33 [2]: 57 Back in Cordoba itself, Abd ar-Rahman III also expanded the courtyard (sahn) of the Great Mosque and built its first true minaret. The minaret, with a cuboid shape about 47 metres (154 ft) tall, became the model followed for later minarets in the region.[2]: 61–63 Abd ar-Rahman III's cultured son and successor, al-Hakam II, further expanded the mosque's prayer hall, starting in 962. He endowed it with some of its most significant architectural flourishes and innovations, which included a maqsura enclosed by intersecting multifoil arches, four ornate ribbed domes, and a richly-ornamented mihrab with Byzantine-influenced gold mosaics.[1]: 139–151 [6]: 70–86

A much smaller but notable work from the late caliphate period is the Bab al-Mardum Mosque (now known as the Church of San Cristo de la Luz) in Toledo, which has a nine-bay layout covered by a variety of ribbed domes and an exterior façade with an Arabic inscription carved in brick. Other monuments from the Caliphate period in al-Andalus include some of Toledo's old city gates (e.g. Puerta de Bisagra), the former mosque (and later monastery) of Almonaster la Real, the Castle of Tarifa, the Burgalimar Castle, the Caliphal Baths of Cordoba, and, possibly, the Baths of Jaen.[6]: 88–103

In the 10th century much of northern Morocco also came directly within the sphere of influence of the Ummayyad Caliphate of Cordoba, with competition from the Fatimid Caliphate further east.[22] Early contributions to Moroccan architecture from this period include expansions to the Qarawiyyin and Andalusiyyin mosques in Fes and the addition of their square-shafted minarets, carried out under the sponsorship of Abd ar-Rahman III and following the example of the minaret he built for the Great Mosque of Cordoba.[1]: 199, 212

The Fatimid Caliphate

In Ifriqiya, the Fatimids also built extensively, most notably with the creation of a new fortified capital on the coast, Mahdia. Construction began in 916 and the new city was officially inaugurated on 20 February 921, although some construction continued.[2]: 47 In addition to its heavy fortified walls, the city included the Fatimid palaces, an artificial harbor, and a congregational mosque (the Great Mosque of Mahdia). Much of this has not survived to the present day. Fragments of mosaic pavements from the palaces have been discovered from modern excavations.[2]: 48 The mosque is one of the most well-preserved Fatimid monuments in the Maghreb, although it too has been extensively damaged over time and was in large part reconstructed by archeologists in the 1960s.[2]: 49 It consists of a hypostyle prayer hall with a roughly square courtyard. The mosque's original main entrance, a monumental portal projecting from the wall, was relatively unusual at the time and may have been inspired by ancient Roman triumphal arches. Another unusual feature was the absence of a minaret, which may have reflected an early Fatimid rejection of such structures as unnecessary innovations.[2]: 49–51

In 946 the Fatimids began construction of a new capital, al-Mansuriyya, near Kairouan. Unlike Mahdia, which was built with more strategic and defensive considerations in mind, this capital was built as a display of power and wealth. The city had a round layout with the caliph's palace at the center, possibly modeled on the Round City of Baghad. While only sparse remains of the city have been uncovered, it appears to have differed from earlier Fatimid palaces in its extensive use of water. One excavated structure had a vast rectangular courtyard mostly occupied by a large pool. This use of water was reminiscent of earlier Aghlabid palaces at nearby Raqqada and of contemporary palaces at Madinat al-Zahra, but not of older Umayyad and Abbasid palaces further east, suggesting that displays of waterworks were evolving as symbols of power in the Maghreb and al-Andalus.[2]: 58–61

Political fragmentation (11th century)

The Taifas in Al-Andalus

The collapse of the Cordoban caliphate in the early 11th century gave rise to the first

The

Zirids and Hammadids in North Africa

In North Africa, new Berber dynasties such as the Zirids ruled on behalf of the Fatimids, who had moved their base of power to Cairo in the late 10th century. The Zirid palace at 'Ashir (near the present town of Kef Lakhdar in Algeria) was built in 934 by Ziri ibn Manad while in the service of the Fatimid caliph al-Qa'im. It is one of the oldest palaces in the Maghreb to have been discovered and excavated.[13]: 53 It was built in stone and has a carefully-designed symmetrical plan which included a large central courtyard and two smaller courtyards in each of the side wings of the palace. Some scholars believe this design imitated the now-lost Fatimid palaces of Mahdia.[2]: 67 As independent rulers, however, the Zirids of Ifriqiya built relatively few grand structures. They reportedly built a new palace at al-Mansuriyya, a former Fatimid capital near Kairouan, but it has not been found by archeologists.[13]: 123 In Kairouan itself the Great Mosque was restored by Al-Mu'izz ibn Badis. The wooden maqsura within the mosque today is believed to date from this time.[2]: 87 It is the oldest maqsura in the Islamic world to be preserved in situ and was commissioned by al-Mu῾izz ibn Badis in the first half of the 11th century (though later restored). It is notable for its woodwork, which includes an elaborately carved Kufic inscription dedicated to al-Mu'izz.[45][46] The Qubbat al-Bahw, an elegant dome at the entrance of the prayer hall of the Zaytuna Mosque in Tunis, dates from 991 and can be attributed to Al-Mansur ibn Buluggin.[2]: 86–87

The Hammadids, an offshoot of the Zirids, ruled in the central Maghreb (present-day Algeria) during the 11th and 12th centuries. They built an entirely new fortified capital known as Qal'at Bani Hammad, founded in 1007. Although abandoned and destroyed in the 12th century, the city has been excavated by modern archeologists and the site is one of the best-preserved medieval Islamic capitals in the world. It contains several palaces, various amenities, and a grand mosque, in an arrangement that bears similarities to other palace-cities such as Madinat al-Zahra.[13]: 125–126 [2]: 88–93 The largest palace, Qasr al-Bahr ("Palace of the Sea"), was built around an enormous rectangular water basin. The architecture of the site has been compared to Fatimid architecture, but bears specific resemblances to contemporary architecture in the western Maghreb, Al-Andalus, and Arab-Norman Sicily. For example, while the Fatimids usually built no minarets, the grand mosque of Qal'at Bani Hammad has a large square-based minaret with interlacing and polylobed arch decoration, which are features of architecture in al-Andalus.[2]: 88–93 Various remnants of tile decoration have been discovered at the site, including the earliest known use of glazed tile decoration in western Islamic architecture.[2]: 91–93 Archeologists also discovered fragments of plaster which have been identified by some as the earliest appearance of muqarnas ("stalactite" or "honeycomb" sculpting) in the western Islamic world,[47][13]: 133 but their identification as true muqarnas has been questioned or rejected by some other scholars.[48][2]: 93

The Berber Empires (11th–13th centuries)

The late 11th century saw the significant advance of Christian kingdoms into Muslim al-Andalus, particularly with the fall of Toledo to Alfonso VI of Castile in 1085, and the rise of major Berber empires originating in northwestern Africa. The latter included first the Almoravids (11th–12th centuries) and then the Almohads (12th–13th centuries), both of whom created empires that stretched across large parts of western and northern Africa and took over the remaining Muslim territories of al-Andalus in Europe. Both empires had their capital at Marrakesh, which was founded by the Almoravids in the second half of the 11th century.[49] This period is one of the most formative stages of architecture in al-Andalus and the Maghreb, establishing many of the forms and motifs that were refined in subsequent centuries.[1][14][49][50]

Almoravids

The Almoravids made use of Andalusi craftsmen throughout their realms, thus helping to spread the highly ornate architectural style of al-Andalus to North Africa.[2]: 115–119 [14]: 26–30 Almoravid architecture assimilated the motifs and innovations of Andalusi architecture, such as the complex interlacing arches of the Great Mosque in Cordoba and of the Aljaferia palace in Zaragoza, but it also introduced new ornamental techniques from the east, such as muqarnas, and added its own innovations, such as the lambrequin arch and the use of pillars instead of columns in mosques.[14]: 26–30 [51] Stucco-carved decoration began to appear more and more as part of these compositions and would become even more elaborate in subsequent periods.[6]: 155 Almoravid patronage thus marks a period of transition for architecture in the region, setting the stage for future developments.[14]: 30

Some of the oldest and most significant surviving examples of Almoravid religious architecture, although with later modifications, are the Great Mosque of Algiers (1096–1097), the Great Mosque of Tlemcen (1136), and the Great Mosque of Nedroma (1145), all located in Algeria today.[1][2] The highly ornate, semi-transparent plaster dome in front of the mihrab of the Great Mosque of Tlemcen, dating from the reign of Ali ibn Yusuf (r. 1106–1143), is one of the highlights of this period. The design of the dome traces its origins to the earlier ribbed domes of Al-Andalus and, in turn, it probably influenced the design of similar ornamental domes in later mosques in Fez and Taza.[52][2]: 116

In Morocco, the only notable remnants of Almoravid religious architecture are the Qubba Ba'adiyyin, a small but highly ornate ablutions pavilion in Marrakesh, and the Almoravid expansion of the Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fez. These two monuments also contain the earliest clear examples of muqarnas decoration in the region, with the first complete muqarnas vault appearing in the central nave of the Qarawiyyin Mosque.[2]: 114–120 [53] The Almoravid palace of Ali Ibn Yusuf in Marrakesh, excavated in the 20th century, contains the earliest known example of a riad garden (an interior garden symmetrically divided into four parts) in Morocco.[54]: 71 [1]: 404

In present-day Spain, the oldest surviving muqarnas fragments were found in a palace built by Muhammad Ibn Mardanish, the independent ruler of Murcia (1147–1172). The remains of the palace, known as al-Qasr al-Seghir (or Alcázar Seguir in Spanish) are part of the present-day Monastery of Santa Clara in Murcia. The muqarnas fragments are painted with images of musicians and other figures.[2]: 98–100 Ibn Mardanish also constructed what is now known as the Castillejo de Monteagudo, a hilltop castle and fortified palace outside the city that is one of the best-preserved examples of Almoravid-era architecture in the Iberian Peninsula. It has a rectangular plan and contained a large riad garden courtyard with symmetrical reception halls facing each other across the long axis of the garden.[2]: 98–100 [16][55]

Almohads

Almohad architecture showed more restraint than Almoravid architecture in its use of ornamental richness, giving greater attention to wider forms, contours, and overall proportions. Earlier motifs were refined and were given a grander scale. While surface ornament remained important, architects strove for a balance between decorated surfaces and empty spaces, allowing the interaction of light and shadows across carved surfaces to play a role.[14]: 86–88 [4]

The Almohad

The Almohad caliphs constructed their own palace complexes in several cities. They founded the

Arab-Norman architecture in Sicily (11th-12th centuries)

Sicily was progressively brought under Muslim control in the 9th when the Aghlabids conquered it from the Byzantines. The island was subsequently settled by Arabs and Berbers from North Africa. In the following century the island passed into the control of the Fatimids, who left the island under the governorship of the Kalbids. By the mid-11th century the island was fragmented into smaller Muslim states and by the end of that century the Normans had conquered it under the leadership of Robert Guiscard and Roger de Hauteville (Roger I).[59][60]

Virtually no examples of architecture from the period of the

The Palazzo dei Normanni (Palace of the Normans) in Palermo contains the Cappella Palatina, one of the most important masterpieces of this style, built under Roger II in the 1130s and 1140s.[63][64] It combines harmoniously a variety of styles: the Norman architecture and door decor, the Arabic arches and scripts adorning the roof, the Byzantine dome and mosaics. The central nave of the chapel is covered by a large rectangular vault ceiling made of painted wood and carved in muqarnas: the largest rectangular muqarnas vault of its kind.[60]

Marinids, Nasrids, and Zayyanids (13th–15th centuries)

The eventual collapse of the Almohad Empire in the 13th century was precipitated by its defeat at the

The Marinids, who chose

The most famous architectural legacy of the Nasrids in Granada is the Alhambra, a hilltop palace district protected by heavy fortifications and containing some of the most famous and best-preserved palaces of western Islamic architecture. Initially a fortress built by the Zirids in the 11th century (corresponding to the current Alcazaba), it was expanded into a self-contained and well-fortified palace district complete with habitations for servants and workers. The oldest remaining palace there today, built under Muhammad III (ruled 1302–1309), is the Palacio del Partal which, although only partly preserved, demonstrates the typical layout which would be repeated in other palaces nearby: a courtyard centered on a large reflective pool with porticos at either end and a mirador (lookout) tower at one end which looked down on the city from the edge of the palace walls.[70][24][6] The most famous palaces, the Comares Palace and the Palace of the Lions, were added afterwards. The Comares Palace, which includes a lavish hammam (bathhouse) and the Hall of the Ambasadors (a throne room), was begun under Isma'il I (ruled 1314–1325) but mostly constructed under Yusuf I (1333–1354) and Muhammad V (ruled 1354–1359 and 1362–1391).[24][2]: 152 The Palace of the Lions was built under Muhammad V and possibly finished around 1380.[2]: 152 [24]: 142 It features a courtyard with a central marble fountain decorated with twelve lion sculptures. The galleries and chambers around the courtyard are notable for their extremely fine stucco decoration and some exceptional muqarnas vault ceilings.[2]: 160–163 Four other nearby palaces in the Alhambra were demolished at various points after the end of the Reconquista (1492).[24] The summer palace and gardens known as the Generalife were also created nearby – at the end of the 13th century[2]: 164 or in the early 14th century[6]: 204 – in a tradition reminiscent of the Almohad-era Agdal Gardens of Marrakesh and the Marinid Royal Gardens of Fes.[68] The Nasrids also built other structures throughout the city – such as the Madrasa and the Corral del Carbón – and left their mark on other structures and fortifications throughout their territory, though not many significant structures have survived intact to the present-day.[6]

Meanwhile, in the former territories of al-Andalus under the control of the Spanish kingdoms of Léon, Castile and Aragon, Andalusi art and architecture continued to be employed for many years as a prestigious style under new Christian patrons, becoming what is known as Mudéjar art (named after the Mudéjars or Muslims under Christian rule). This type of architecture, created by Muslim craftsmen or by other craftsmen following the same tradition, continued many of the same forms and motifs with minor variations. Numerous examples are found in the early churches of Toledo (e.g. the Church of San Román, 13th century), as well as other cities in Aragon such as Zaragoza and Teruel.[1][18] Among the most famous and celebrated examples is the Alcazar of Seville, which was the former palace of the Abbadids and the Almohads in the city but was rebuilt in by Christian rulers, including Peter the Cruel who added lavish sections in Moorish style starting in 1364 with the help of craftsmen from Granada and Toledo.[2] Other smaller but notable examples in Cordoba include the Chapel of San Bartolomé[71] and the Royal Chapel (Capilla Real) in the Great Mosque (which was converted to a cathedral in 1236).[72][1] Some surviving 13th and 14th-century Jewish synagogues were also built (or rebuilt) in Mudéjar Moorish style while under Christian rule, such as the Synagogue of Santa Maria la Blanca in Toledo (rebuilt in its current form in 1250),[73] Synagogue of Cordoba (1315),[74] and the Synagogue of El Tránsito (1355–1357).[75][76]

Further east, in Algeria, the Berber Zayyanid or Abd al-Wadid dynasty controlled

The Hafsids of Tunisia (13th–16th centuries)

In Ifriqiya (Tunisia), the Hafsids, a branch of the Almohad ruling class, declared their independence from the Almohads in 1229 and developed their own state which came to control much of the surrounding region. They were also significant builders, particularly under the reigns of successful leaders like

The

The Hafsids also introduced the first madrasas to the region, beginning with the

The Hafsids were eventually supplanted by the Ottomans who took over most of the Maghreb in the 16th century, with the exception of Morocco, which remained an independent kingdom.[22] This resulted in an even greater divergence between the architecture of Morocco to the west, which continued to follow essentially the same Andalusi-Maghrebi traditions of art as before, and the architecture of Algeria and Tunisia to the east, which increasingly blended influences from Ottoman architecture into local designs.[2]

The Sharifian dynasties in Morocco: Saadians and 'Alawis (16th century and after)

In Morocco, after the Marinids came the

The Saadians, especially under the sultans Abdallah al-Ghalib and Ahmad al-Mansur, were extensive builders and benefitted from great economic resources at the height of their power in the late 16th century. In addition to the Saadian Tombs, they also built several major mosques in Marrakesh including the Mouassine Mosque and the Bab Doukkala Mosque, which are notable for being part of larger multi-purpose charitable complexes including several other structures like public fountains, hammams, madrasas, and libraries. This marked a shift from the previous patterns of architectural patronage and may have been influenced by the tradition of building such complexes in Mamluk architecture in Egypt and the külliyes of Ottoman architecture.[56][80] The Saadians also rebuilt the royal palace complex in the Kasbah of Marrakesh for themselves, where Ahmad al-Mansur constructed the famous El Badi Palace (built between 1578 and 1593) which was known for its superlative decoration and costly building materials including Italian marble.[56][80]

The 'Alawis, starting with Moulay Rashid in the mid-17th century, succeeded the Saadians as rulers of Morocco and continue to be the reigning monarchy of the country to this day. As a result, many of the mosques and palaces standing in Morocco today have been built or restored by the 'Alawis at some point or another in recent centuries.[65][56][36] Ornate architectural elements from Saadian buildings, most infamously from the lavish El Badi Palace, were also stripped and reused in buildings elsewhere during the reign of Moulay Isma'il (1672–1727).[80] Moulay Isma'il is also notable for having built a vast imperial capital in Meknes, where the remains of his monumental structures can still be seen today. In 1765 Sultan Mohammed ben Abdallah (one of Moulay Isma'il's sons) started the construction of a new port city called Essaouira (formerly Mogador), located along the Atlantic coast as close as possible to his capital at Marrakesh, to which he tried to move and restrict European trade.[22]: 241 [2]: 264 He hired European architects to design the city, resulting in a relatively unique historic city built by Moroccans but with Western European architecture, particularly in the style of its fortifications. Similar maritime fortifications or bastions, usually called a sqala, were built at the same time in other port cities like Anfa (present-day Casablanca), Rabat, Larache, and Tangier.[1]: 409 Late sultans were also significant builders. Up until the late 19th century and early 20th century, both the sultans and their ministers continued to build beautiful palaces, many of which are now used as museums or tourist attractions, such as the Bahia Palace in Marrakesh, the Dar Jamaï in Meknes, and the Dar Batha in Fes.[17][81]

Ottoman rule in Algeria and Tunisia (16th century and after)

Over the course of the 16th century the central and eastern Maghreb – Algeria, Tunisia, and

Tunisia

In Tunis, the

The

It wasn't until the end of the 17th century that the first and only Ottoman-style domed mosque in Tunisia was built: the Sidi Mahrez Mosque, begun by Muhammad Bey and completed by his successor, Ramadan ibn Murad, between 1696 and 1699. The mosque's prayer hall is covered by a dome system typical of Classical Ottoman architecture and first employed by Sinan for the Şehzade Mosque (c. 1548) in Istanbul: a large central dome flanked by four semi-domes, with four smaller domes at the corners and pendentives in the transitional zones between the semi-domes. The interior is decorated with marble paneling and Ottoman Iznik tiles.[2]: 226–227

Algeria

During this period Algiers developed into a major town and witnessed regular architectural patronage, and as such most of the major monuments from this period are concentrated there. By contrast, the city of Tlemcen, the former major capital of the region, went into relative decline and saw far less architectural activity.[2]: 234–236 Mosque architecture in Algiers during this period demonstrates the convergence of multiple influences as well as peculiarities that may be attributed to the innovations of local architects.[2]: 238–240 Domes of Ottoman influence were introduced into the design of mosques, but minarets generally continued to be built with square shafts instead of round or octagonal ones, thus retaining local tradition, unlike contemporary architecture in Ottoman Tunisia and other Ottoman provinces, where the "pencil"-shaped minaret was a symbol of Ottoman sovereignty.[2]: 238 [82][83]

The oldest surviving mosque from the Ottoman period in Algeria is the Ali Bitchin (or 'Ali Bitshin) Mosque in Algiers, commissioned by an admiral of the same name, a convert of Italian origin, in 1622.[2]: 238 The mosque is built on top of a raised platform and was once associated with various annexes including a hospice, a hammam, and a mill. A minaret and public fountain stand on its northeast corner. The interior prayer hall is centered around a square space covered by a large octagonal dome supported on four large pillars and pendentives. This space is surrounded on all four sides with galleries or aisles covered by rows of smaller domes. On the west side of the central space this gallery is two bays deep (i.e. composed of two aisles instead of one), while on the other sides, including on the side of the mihrab, the galleries are just one bay deep.[2]: 238 Several other mosques in Algiers built from the 17th to early 19th centuries had a similar floor plan.[2]: 237–238 [1]: 426–432 This particular design was unprecedented in the Maghreb. The use of a large central dome was a clear connection with Ottoman architecture. However, the rest of the layout is quite different from the mosques of metropolitan Ottoman architecture in cities like Istanbul. Some scholars, such as Georges Marçais, suggested that the architects or patrons could have been influenced by Ottoman-era mosques built in the Levantine provinces of the empire, where many of the rulers of Algiers had originated.[2]: 238 [1]: 432

The most notable monument from this period in Algiers is the New Mosque (Djamaa el Djedid) in Algiers, built in 1660–1661.[2]: 239 [1]: 433 The mosque has a large central dome supported by four pillars, but instead of being surrounded by smaller domes it is flanked on four sides by wide barrel-vaulted spaces, with small domed or vaulted bays occupying the corners between these barrel vaults. The barrel-vaulted space on the north side of the dome (the entrance side) is elongated, giving the main vaulted spaces of the mosque a cross-like configuration resembling a Christian cathedral.[2]: 239–241 The mosque's minaret has a traditional form with a square shaft surmounted by a small lantern structure. Its simple decoration includes tilework; the clock faces visible today were added at a later period. The mihrab has a more traditional western Islamic form, with a horseshoe-arch shape and stucco decoration, although the decoration around it is crowned with Ottoman-style half-medallion and quarter-medallion shapes.[2]: 239–241 [1]: 433–434 The mosque's overall design and its details thus attest to an apparent mix of Ottoman, Maghrebi, and European influences. As the architect is unknown, Jonathan Bloom suggests that it could very well have been a local architect who simply took the general idea of Ottoman mosque architecture and developed his own interpretation of it.[2]: 240–241

Beyond the Islamic world

Certain aspects and traditions of Moorish architecture were brought to the Iberian colonies in the Americas. Günter Weimer outlines the influence of Arab and Amazigh substrates in popular architecture in Brazil, noting the considerable number of architectural terms in Portuguese inherited from Arabic, including muxarabi (مشربية) and açoteia (السُطيحة lit. 'little roof').[85]: 91–107 Elements of Mudéjar architecture, derived from Islamic architectural traditions and assimilated into Spanish architecture, are found in the architecture of the Spanish colonies.[86][87] The Islamic and Mudéjar style of decorative wooden ceilings, known in Spanish as armadura, proved particularly popular in both Spain and its colonies.[18][87] Examples of Mudéjar-influenced colonial architecture are concentrated in Mexico and Central America, including some in what is now the southwestern United States.[88]: 300

Later, particularly in the 19th century, the Moorish Islamic style was frequently imitated by the Neo-Moorish or Moorish Revival style which emerged in the Europe and North America as part of the Romanticist interest in the "Orient".[19] The term "Moorish" or "neo-Moorish" sometimes also covered an appropriation of motifs from a wider range of Islamic architecture.[19][89] This style was a recurring choice for Jewish synagogue architecture of the era, where it was seen as an appropriate way to mark Judaism's non-European origins.[19][90][91] Similar to Neo-Moorish, Néo-Mudéjar was a revivalist style evident in late 19th and early 20th-century Spain and in some Spanish Colonial architecture in northern Morocco.[92][93][20] During the French occupation of Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco, the French colonial administration also encouraged, in some cases, the use of indigenous North African or arabisant ("Arabizing") motifs in new buildings.[94]

Architectural features

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

The architecture of the western Islamic world is exemplified by mosques, madrasas, palaces, fortifications, hammams (bathhouses), funduqs (

As scholar

Arches

Horseshoe arch

Perhaps the most characteristic arch type of western Islamic architecture generally is the so-called "Moorish" or "horseshoe" arch. This is an arch where the curves of the arch continue downward past the horizontal middle axis of the circle and begin to curve towards each other, rather than just forming a half circle.[17]: 15 This arch profile became nearly ubiquitous in the region from the very beginning of the Islamic period.[1]: 45 The origin of this arch appear to date back to the preceding Byzantine period across the Mediterranean, as versions of it appear in Byzantine-era buildings in Cappadocia, Armenia, and Syria. They also appear frequently in Visigothic churches in the Iberian peninsula (5th–7th centuries). Perhaps due to this Visigothic influence, horseshoe arches were particularly predominant afterwards in al-Andalus under the Umayyads of Cordoba, although the "Moorish" arch was of a slightly different and more sophisticated form than the Visigothic arch.[1]: 163–164 [6]: 43 Arches were not only used for supporting the weight of the structure above them. Blind arches and arched niches were also used as decorative elements. The mihrab of a mosque was almost invariably in the shape of horseshoe arch.[1]: 164 [17]

Starting in the Almoravid period, the first pointed or "broken" horseshoe arches began to appear in the region and became more widespread during the Almohad period. This arch is likely of North African origin, since pointed arches were already present in earlier Fatimid architecture further east.[1]: 234

Polylobed arch

Polylobed (or multifoil) arches, have their earliest precedents in Fatimid architecture in Ifriqiya and Egypt and had also appeared in Andalusi Taifa architecture such as the Aljaferia palace and the Alcazaba of Malaga, which elaborated on the existing examples of al-Hakam II's extension to the Great Mosque of Cordoba. In the Almoravid and Almohad periods, this type of arch was further refined for decorative functions while horseshoe arches continued to be standard elsewhere.[1]: 232–234 Some early examples appear in the Great Mosque of Tlemcen (in Algeria) and the Mosque of Tinmal.[1]: 232

-

Interlacing polylobed arches at the Alcazaba of Malaga in Spain (11th century)

-

A polylobed arch in the Mosque of Tinmal in Morocco (mid-12th century)

-

Polylobed arches in the Mudéjar-style Patio de las Doncellas at the Alcazar of Seville in Spain (14th century)

"Lambrequin" arch

The so-called "lambrequin" arch,

-

Lambrequin arches in the Mosque of Tinmal (mid-12th century)

-

A lambrequin or "muqarnas" arch with muqarnas decoration in the Madrasa al-Attarine, Fes (1323-1325)

-

A lambrequin/muqarnas arch (top) in the gallery of the Courtyard of the Lions in the Alhambra, Granada (14th century)

-

Lambrequin arches in the Bahia Palace in Marrakesh, Morocco (late 19th century)

Domes

Although domes and vaulting were not extensively used in western Islamic architecture, domes were still employed as decorative features to highlight certain areas, such as the space in front of the mihrab in a mosque. In the extension of the Great Mosque of Córdoba by al-Hakam II in the late 10th century, three domes were built over the maqsura (the privileged space in front of the mihrab) and another one in the central nave or aisle of the prayer hall at the beginning of the new extension. These domes were constructed as ribbed vaults. Rather than meeting in the centre of the dome, the "ribs" intersect one another off-center, forming a square or an octagon in the centre.[97]

The ribbed domes of the Mosque of Córdoba served as models for later mosque buildings in Al-Andalus and the Maghreb. At around 1000 AD, the Bab al-Mardum Mosque in Toledo was constructed with a similar, eight-ribbed dome, surrounded by eight other ribbed domes of varying design.[2]: 79 Similar domes are also seen in the mosque building of the Aljafería of Zaragoza. The architectural form of the ribbed dome was further developed in the Maghreb: the central dome of the Great Mosque of Tlemcen, a masterpiece of the Almoravids founded in 1082 and redecorated in 1136, has twelve slender ribs, the shell between the ribs is filled with filigree stucco work.[97][98]

In Ifriqiya, certain domes from the 9th and 10th centuries, of a quite different style, are also particularly accomplished in their design and decoration. These are the 9th-century (Aghlabid) dome in front of the mihrab in the Great Mosque of Kairouan and the 10th-centuy (Zirid) Qubbat al-Bahw dome in the Al-Zaytuna Mosque in Tunis. Both are elegant ribbed domes with stonework flourishes such as decorative niches, inscriptions, and shell-shaped squinches.[2]: 30–32, 86–87

-

The ribbed dome at the beginning of al-Hakam II's extension of the Great Mosque of Cordoba (circa 965)

-

The ribbed dome in front of the mihrab of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, covered in mosaics (circa 965)

-

Smaller ribbed domes in the Bab al-Mardum Mosque in Toledo (c. 1000)

-

Detail of decoration inside the dome before the mihrab of the Great Mosque of Kairouan (circa 836)

-

The Qubbat al-Bahw (or Qubbat al-Bahu) at the Al-Zaytuna Mosque in Tunis (991)

Decorative motifs

Floral and vegetal motifs

Arabesques, or stylized floral and vegetal motifs, derive from a long tradition of similar motifs in Syrian, Hellenistic, and Roman architectural ornamentation.[1][17] Early arabesque motifs in Umayyad Cordoba, such as those seen at the Great Mosque or Madinat al-Zahra, continued to make use of acanthus leaves and grapevine motifs from this Hellenistic tradition. Almoravid and Almohad architecture made more use of a general striated leaf motif, often curling and splitting into unequal parts along an axis of symmetry.[1][17] Palmettes and, to a lesser extent, seashell and pine cone images were also featured.[1][17] In the late 16th century, Saadian architecture sometimes made use of a mandorla-type (or almond-shaped) motif which may have been of Ottoman influence.[80]: 128

-

Madinat al-Zahra in Spain, carved in panels of limestone(10th century)

-

Arabesques carved in stucco over an archway in the al-Attarine Madrasa in Fes (14th century)

-

Arabesques in stucco in the Court of the Myrtles at the Alhambra (14th century)

Sebka motif

Various types of interlacing lozenge-like motifs are heavily featured on the surface of minarets starting in the Almohad period (12th–13th centuries) and are later found in other decoration such as carved stucco along walls in Marinid and Nasrid architecture, eventually becoming a standard feature in the western Islamic ornamental repertoire in combination with arabesques.[17][1] This motif, typically called sebka (meaning "net"),[24]: 80 [99] is believed by some scholars to have originated with the large interlacing arches in the 10th-century extension of the Great Mosque of Cordoba by Caliph al-Hakam II.[1]: 257–258 It was then miniaturized and widened into a repeating net-like pattern that can cover surfaces. This motif, in turn, had many detailed variations. One common version, called darj wa ktaf ("step and shoulder") by Moroccan craftsmen, makes use of alternating straight and curved lines which cross each other on their symmetrical axes, forming a motif that looks roughly like a fleur-de-lys or palmette shape.[1]: 232 [17]: 32 Another version, also commonly found on minarets in alternation with the darj wa ktaf, consists of interlacing multifoil/polylobed arches which form a repeating partial trefoil shape.[17]: 32, 34

-

A sebka or darj wa ktaf motif on one of the facades of the Hassan Tower in Rabat, Morocco (late 12th century)

-

Variation of the sebka motif with a trefoil-like shape on theKasbah Mosque in Marrakesh, Morocco (late 12th century)

-

Darj wa ktaf motif on Bab Mansour in Meknes, Morocco (early 18th century)

Geometric patterns

Geometric patterns, most typically making use of intersecting straight lines which are rotated to form a radiating star-like pattern, were common in Islamic architecture generally and across Moorish architecture. These are found in carved stucco and wood decoration, and most notably in zellij mosaic tilework which became commonplace in Moorish architecture from the 13th century onward. Other polygon motifs are also found, often in combination with arabesques.[1][17]

In addition to zellij tiles, geometric motifs were also predominant in the decoration and composition of wooden ceilings. One of the most famous examples of such ceilings, considered the masterpiece of its kind, is the ceiling of the Salón de Embajadores in the Comares Palace at the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. The ceiling, composed of 8,017 individual wooden pieces joined together into a pyramid-like dome, consists of a recurring 16-pointed star motif which is believed to have symbolized the

-

Eight-pointed and sixteen-pointed star motifs in zellij (azelujos) tilework at the Sala del Mexuar in the Alhambra in Granada, Spain (14th century)[101]

-

Geometric patterns in stucco decoration at the Hall of the Two Sisters in the Alhambra (14th century)

-

Twelve-pointed star motifs in zellij tilework at the Saadian Tombs in Marrakesh, Morocco (16th century)

-

Geometric motifs on the bronze plating of the doors of the Al-Attarine Madrasa (14th century)

-

The enormous wooden ceiling of the Salón de Embajadores (the Nasrid throne room) at the Alhambra in Granada, Spain (14th century)

-

Another example of geometric patterns in a (smaller and simpler) wooden ceiling in the Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakesh (16th century)

-

Painted geometric motifs on a wooden ceiling in the Bahia Palace in Marrakesh (late 19th century)

Arabic calligraphy

Many Islamic monuments feature inscriptions of one kind or another which serve to either decorate or inform, or both. Arabic calligraphy, as in other parts of the Muslim world, was also an art form. Many buildings had foundation inscriptions which record the date of their construction and the patron who sponsored it. Inscriptions could also feature Qur'anic verses, exhortations of God, and other religiously significant passages. Early inscriptions were generally written in the Kufic script, a style where letters were written with straight lines and had fewer flourishes.[1][17]: 38 At a slightly later period, mainly in the 11th century, Kufic letters were enhanced with ornamentation, particularly to fill the empty spaces that were usually present above the letters. This resulted in the addition of floral forms or arabesque backgrounds to calligraphic compositions.[1]: 251 In the 12th century the cursive Naskh script began to appear, though it only became commonplace in monuments from the Marinid and Nasrid period (13th–15th century) onward.[1]: 250, 351–352 [17]: 38 Kufic was still employed, especially for more formal or solemn inscriptions such as religious content.[17]: 38 [1]: 250, 351–352 However, from the 13th century onward Kufic became increasingly stylized and almost illegible.[102] In the decoration of the Alhambra, one can find examples of "Knotted" Kufic, a particularly elaborate style where the letters tie together in intricate knots.[103][104] This style is also found in other parts of the Islamic world and may have had its origins in Iran.[105][106] The extensions of the letters could turn into strips or lines that continued to form more motifs or form the edges of a cartouche encompassing the rest of the inscription.[107]: 269 As a result, Kufic script could be used in a more strictly decorative form, as the starting point for an interlacing or knotted motif that could be woven into a larger arabesque background.[1]: 351–352

-

Kufic inscriptions carved into the façade of the Mosque of the Three Doors in Kairouan, Tunisia, dating from 866

-

Late 12th-century Kufic inscription carved into stone on the Almohad gate of Bab Agnaou in Marrakesh

-

Kufic script with floral and interlacing flourishes, painted on tile, in the Al-Attarine Madrasa, Fes, Morocco (early 14th century)

-

Cursive (Naskh) Arabic script carved into stucco in the al-Attarine Madrasa in Fes (early 14th century)

-

Calligraphic inscription carved into wood in the Sahrij Madrasa in Fes, surrounded by other arabesque decoration (early 14th century)

-

Calligraphy in the Salón de Embajadores in the Alhambra, Granada (14th century): above is the Nasrid motto ("There is no conqueror but God") in cursive script, repeated more than once, while below is a larger inscription in "Knotted" Kufic

Muqarnas

Muqarnas (also called mocárabe in Spain), sometimes referred to as "honeycomb" or "stalactite" carvings, consists of a three-dimensional geometric prismatic motif which is among the most characteristic features of Islamic architecture. This technique originated further east in Iran before spreading across the Muslim world.[1]: 237 It was first introduced into al-Andalus and the western Maghreb by the Almoravids, who made early use of it in early 12th century in the Qubba Ba'adiyyin in Marrakesh and in the Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fes.[14][51][1]: 237 While the earliest forms of muqarnas in Islamic architecture were used as squinches or pendentives at the corners of domes,[1]: 237 they were quickly adapted to other architectural uses. In the western Islamic world they were particularly dynamic and were used, among other examples, to enhance entire vaulted ceilings, fill in certain vertical transitions between different architectural elements, and even to highlight the presence of windows on otherwise flat surfaces.[1][65][17]

-

Small muqarnas cupola inside the mihrab of the Mosque of Tinmal (mid-12th century)

-

Closer view of the details at the apex of a muqarnas dome in the Sala de los Reyes in the Alhambra

-

Extreme close-up of carved and painted details in constituent niches of a muqarnas dome in the Sala de los Reyes in the Alhambra

-

Rectangular muqarnas vault carved in cedar wood at the Bou Inania Madrasa in Fes, Morocco (mid-14th century)

-

Muqarnas carved in wood in theDar al-Makhzen of Tangier(17th century or later)

Zellij (tilework)

Tilework, particularly in the form of mosaic tilework called zellij, is a standard decorative element along lower walls and for the paving of floors across the region. It consists of hand-cut pieces of faience in different colours fitted together to form elaborate geometric motifs, often based on radiating star patterns.[65][1] Zellij made its appearance in the region during the 10th century and became widespread by the 14th century during the Marinid and Nasrid period.[65] It may have been inspired or derived from Byzantine mosaics and then adapted by Muslim craftsmen for faience tiles.[65]

In the traditional Moroccan craft of zellij-making, the tiles are first fabricated in glazed squares, typically 10 cm per side, then cut by hand into a variety of pre-established shapes (usually memorized by heart) necessary to form the overall pattern.[17] This pre-established repertoire of shapes combined to generate a variety of complex patterns is also known as the hasba method.[108] Although the exact patterns vary from case to case, the underlying principles have been constant for centuries and Moroccan craftsmen are still adept at making them today.[17][108]

Riads and gardens

A riad (sometimes spelled riyad; Arabic: رياض) is an interior garden found in many Moorish palaces and mansions. It is typically rectangular and divided into four parts along its central axes, with a fountain at its middle.[54] Riad gardens probably originated in Persian architecture (where it is also known as chahar bagh) and became a prominent feature in Moorish palaces in Spain (such Madinat al-Zahra, the Aljaferia, and the Alhambra).[54] In Morocco, they became especially widespread in the palaces and mansions of Marrakesh, where the combination of available space and warm climate made them particularly appealing.[54] The term is nowadays applied in a broader way to traditional Moroccan houses that have been converted into hotels and tourist guesthouses.[109][110]

Many royal palaces were also accompanied by vast pleasure gardens, sometimes built outside the main defensive walls or within their own defensive enclosure. This tradition is evident in the gardens of the Madinat al-Zahra built by the Caliphs of Cordoba (10th century), in the Agdal Gardens south of the Kasbah of Marrakesh created by the Almohads (12th century), the Mosara Garden created by the Marinids north of their palace-city of Fes el-Jdid (13th century), and the Generalife created by the Nasrids east of the Alhambra (13th century).[1][56][68]

Building types

Mosques

Mosques are the main place of worship in Islam. Muslims are called to prayer five times a day and participate in prayers together as a community, facing towards the qibla (direction of prayer). Every neighbourhood normally had one or many mosques to accommodate the spiritual needs of its residents. Historically, there was a distinction between regular mosques and "Friday mosques" or "great mosques", which were larger and had a more important status by virtue of being the venue where the khutba (sermon) was delivered on Fridays.[36] Friday noon prayers were considered more important and were accompanied by preaching, and also had political and social importance as occasions where news and royal decrees were announced, as well as when the current ruler's name was mentioned. In the early Islamic era there was typically only one Friday mosque per city, but over time Friday mosques multiplied until it was common practice to have one in every neighbourhood or district of the city.[111][96] Mosques could also frequently be accompanied by other facilities which served the community.[96][56]

Mosque architecture in Al-Andalus and the Maghreb was heavily influenced from the beginning by major well-known mosques in early cultural centers like the Great Mosque of Kairouan and the Great Mosque of Cordoba.[1][2][49] Accordingly, most mosques in the region have roughly rectangular floor plans and follow the hypostyle format: they consist of a large prayer hall upheld and divided by rows of horseshoe arches running either parallel or perpendicular to the qibla wall (the wall towards which prayers faced). The qibla (direction of prayer) was always symbolized by a decorative niche or alcove in the qibla wall, known as a mihrab.[17] Next to the mihrab there was usually a symbolic pulpit known as a minbar, usually in the form of a staircase leading to a small kiosk or platform, where the imam would stand to deliver the khutba. The mosque also normally included a sahn (courtyard) which often had fountains or water basins to assist with ablutions. In early periods this courtyard was relatively minor in proportion to the rest of the mosque, but in later periods it became a progressively larger until it was equal in size to the prayer hall and sometimes larger.[80][96]

Medieval hypostyle mosques also frequently followed the "T-type" model established in the Almohad period. In this model the aisle or "nave" between the arches running towards the mihrab (and perpendicular to the qibla wall) was wider than the others, as was also the aisle directly in front of and along the qibla wall (running parallel to the qibla wall); thus forming a T-shaped space in the floor plan of the mosque which was often accentuated by greater decoration (e.g. more elaborate arch shapes around it or decorative cupola ceilings at each end of the "T").[96][80][56]

Lastly, mosque buildings were distinguished by their minarets: towers from which the muezzin issues the call to prayer to the surrounding city. (This was historically done by the muezzin climbing to the top and projecting his voice over the rooftops, but nowadays the call is issued over modern megaphones installed on the tower.) Minarets traditionally have a square shaft and are arranged in two tiers: the main shaft, which makes up most of its height, and a much smaller secondary tower above this which is in turn topped by a finial of copper or brass spheres.[1][2] Some minarets in North Africa have octagonal shafts, though this is more characteristic of certain regions or periods.[65][23] Inside the main shaft a staircase, and in other cases a ramp, ascends to the top of the minaret.[1][2]

The whole structure of a mosque was also orientated or aligned with the direction of prayer, such that mosques were sometimes orientated in a different direction from the rest of the buildings or streets around it.

Synagogues

Synagogues had a very different layout from mosques but in North Africa and Al-Andalus they often shared similar decorative trends as the traditional Islamic architecture around them, such as

Madrasas

The madrasa was an institution which originated in northeastern Iran by the early 11th century and was progressively adopted further west.[1][17] These establishments provided higher education and served to train Islamic scholars, particularly in Islamic law and jurisprudence (fiqh), most commonly in the Maliki branch of Sunni legal thought. The madrasa in the Sunni world was generally antithetical to more "heterodox" religious doctrines, including the doctrine espoused by the Almohad dynasty. As such, in the westernmost parts of the Islamic world it only came to flourish in the late 13th century, after the Almohads, under the Marinid, Zayyanid, and Hafsid dynasties.[1][2]

Madrasas played an important role in training the scholars and professionals who operated the state bureaucracy.[77] To dynasties like the Marinids, madrasas also played a part in bolstering the political legitimacy of their rule. They used this patronage to encourage the loyalty of the country's influential but independent religious elites and also to portray themselves to the general population as protectors and promoters of orthodox Sunni Islam.[1][77] In other parts of the Muslim world, the founders of madrasas could name themselves or their family members as administrators of the foundation's waqf (a charitable and inalienable endowment), making them a convenient means of protecting family fortunes, but this was not allowed under the Maliki school of law that was dominant in the western Islamic lands. As a result, the construction of madrasas was less prolific in the Maghreb and in al-Andalus than it was further east. Madrasas in this region are also frequently named after their location or some other distinctive physical feature, rather than after their founders (as was common further east).[2]: 178

Madrasas also played a supporting role to major learning institutions of the region like the Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fes; in part because, unlike the mosque, they provided accommodations for students who came from outside the city.[17]: 137 [37]: 110 Many of these students were poor, seeking sufficient education to gain a higher position in their home towns, and the madrasas provided them with basic necessities such as lodging and bread.[36]: 463 Nonetheless, madrasas were also teaching institutions in their own right and offered their own courses, with some Islamic scholars making their reputation by teaching at certain madrasas.[37]: 141

Madrasas were generally centered around a main courtyard with a central fountain, off which other rooms could be accessed. Student living quarters were typically distributed on an upper floor around the courtyard. Many madrasas also included a prayer hall with a mihrab, though only the Bou Inania Madrasa of Fes officially functioned as a full mosque and featured its own minaret.[67][1][2]

Mausoleums and zawiyas

Most

Funduqs (merchant inns)

A funduq (also spelled foundouk or fondouk; Arabic: فندق) was a caravanserai or commercial building which served as both an inn for merchants and a warehouse for their goods and merchandise.[1][17][54] In North Africa some funduqs also housed the workshops of local artisans.[36] As a result of this function, they also became centers for other commercial activities such as auctions and markets.[36] They typically consisted of a large central courtyard surrounded by a gallery, around which storage rooms and sleeping quarters were arranged, frequently over multiple floors. Some were relatively simple and plain, while others, like the Funduq al-Najjarin in Fes, were quite richly decorated.[65] While many structures of this kind can be found in historic North African cities, the only one in Al-Andalus to have been preserved is the Nasrid-era Corral del Carbón in Granada.[119][2]

Hammams (bathhouses)

Hammams (Arabic: حمّام) are

Palaces

The main palaces of rulers were usually located inside a separate fortified district or citadel of the capital city. These citadels included a complex of different structures including administrative offices, official venues for ceremonies and receptions, functional amenities (such as warehouses, kitchens, and hammams), and the private residences of the ruler and his family. Although palace architecture varied from one period and region to the next, certain traits recurred such as the predominance of courtyards and internal gardens around which elements of the palace were typically centered.[1][13]

In some cases, rulers were installed in the existing fortified citadel of the city, such as the many

Rulers with enough resources sometimes founded entirely separate and autonomous royal cities outside their capital cities, such as Madinat al-Zahra, built by Abd ar-Rahman III outside Cordoba, or Fes el-Jdid built by the Marinids outside old Fez. Some rulers even built entirely new capital cities centered on their palaces, such as the Qal'at Bani Hammad, founded in 1007 by the Hammadids in present-day Algeria, and Mahdia, begun in 916 by the Fatimid Caliphs in present-day Tunisia.[13] In many periods and regions rulers also built outlying private estates with gardens in the countryside. As early as the 8th century, for example, Abd ar-Rahman I possessed such estates in the countryside outside Cordoba. The later Nasrid-built Generalife, located on the mountainside a short distance outside the Alhambra, is also an example of outlying residence and garden made for the private use of the rulers. Moroccan sultans also built pleasure pavilions or residences within the vast gardens and orchards that they maintained outside their cities, notably the Menara Gardens and Agdal Gardens on the outskirts of Marrakesh.[1][13]

Fortifications

In Al-Andalus

The remains of castles and fortifications from various periods of Al-Andalus have survived across Spain and Portugal, often situated on hilltops and elevated positions that command the surrounding countryside. A large number of Arabic terms were used to denote the different types and functions of these structures, many of which were borrowed into Spanish and are found in numerous

In the Umayyad period (8th–10th centuries) an extensive network of fortifications stretched in a wide line roughly from Lisbon in the west then up through the Central System of mountains in Spain, around the region of Madrid, and finally up to the areas of Navarre and Huesca, north of Zaragoza, in the east.[126]: 63 In addition to these border defenses, castles and fortified garrisons existed in the interior regions of the realm as well.[6] Such fortifications were built from the very beginning of Muslim occupation in the 8th century, but a larger number of remaining examples date from the Caliphal period of the 10th century. Some notable examples from this period include the Castle of Gormaz, the Castle of Tarifa, the Alcazaba of Trujillo, the Alcazaba of Guadix, the Burgalimar Castle at Baños de la Encina, and the Alcazaba of Mérida.[6][126][127] The castle of El Vacar near Cordoba is an early example of a rammed-earth fortification in Al-Andalus, likely dating from the Emirate period (756–912), while the castle at Baños de la Encina, dating from later in the 10th century, is a more imposing example of rammed earth construction.[128][126] Many of these early fortifications had relatively simple architecture with no barbicans and only a single line of walls. The gates were typically straight entrances with an inner and outer doorway (often in the form of horseshoe arches) on the same axis.[6]: 100, 116 The castles typically had quadrangular layouts with walls reinforced by rectangular towers.[126]: 67 To guarantee a protected access to water even in times of siege, some castles had a tower built on a riverbank which was connected to the main castle via a wall, known in Spanish as a coracha. One of the oldest examples of this can be found at Calatrava la Vieja (9th century), while a much later example is the tower of the Puente del Cadi below the Alhambra in Granada.[126]: 71 The Alcazaba of Mérida also features an aljibe (cistern) inside the castle which draws water directly from the nearby river.[129][130] Moats were also used as defensive measures up until the Almohad period.[126]: 71–72

In addition to the more sizeable castles, there was a proliferation of smaller castles and forts which held local garrisons, especially from the 10th century onward.[126]: 65 The authorities also built multitudes of small, usually round, watch towers which could rapidly send messages to each other via fire or smoke signals. Using this system of signals, a coded message from Soria in northern Spain, for example, could arrive in Cordoba after as little as five hours. The Watchtower of El Vellón, near Madrid, is one surviving example, along with others in the region. This system continued to be used even up until the time of Philip II in the 16th century.[126]: 66

Following the collapse of the Caliphate in the 11th century, the resulting political insecurity encouraged further fortification of cities. The Zirid walls of Granada along the northern edge of the Albaicin today (formerly the Old Alcazaba of the city) date from this time, as do the walls of Niebla, the walls of Jativa, and the walls of Almeria and its Alcazaba.[6]: 115 The Alcazaba of Málaga also dates from this period but was later redeveloped under the Nasrids. Traces of an 11th-century fortress also exist on the site of Granada's current Alcazaba in the Alhambra.[6] Military architecture also became steadily more complex. Fortified gates began to regularly include bent entrances – meaning that their passage made one or more right-angle turns to slow down any attackers.[6]: 116 Precedents for this type of gate existed as far back as the mid-9th century, with a notable example from this time being the Bab al-Qantara (or Puerta del Alcántara today) in Toledo.[88]: 284 [126]: 71

Later on, the Almohads (12th and early 13th centuries) were particularly active in the restoration and construction of fortresses and city walls across the regions under their control to counter the growing threat of the Christian Reconquista. The fortress of Alcalá de Guadaíra is a clear example dating from this time, as well as the Paderne Castle in present-day Portugal.[6]: 166 [127] The walls of Seville and Silves also date from this time, both of them either built, restored, or expanded by the Almoravids and Almohads.[127][132][133][134] Military technology again became more sophisticated, with barbicans appearing in front of city walls and albarrana towers appearing as a recurring innovation.[6]: 166 Both Cordoba and Seville were reinforced by the Almohads with a set of double walls in rammed earth, consisting of a main wall with regular bastion towers and a smaller outer wall, both topped by a walkway (chemin de ronde) with battlements.[1]: 225 Fortification towers also became taller and more massive, sometimes with round or polygonal bases but more commonly still rectangular. Some of the more famous tower fortifications from this period include the Calahorra Tower in Cordoba, which guarded the outer end of the old Roman bridge, and the Torre del Oro in Seville, a dodecagonal tower which fortified a corner of the city walls and which, along with another tower across the river, protected the city's harbour.[6]: 166

In the 13th–15th centuries, during the final period of Muslim rule in Al-Andalus, fortresses and towns were again refortified by either the Nasrids or (in fewer cases) the Marinids. In addition to the fortifications of Granada and its Alhambra, the Nasrids built or rebuilt the Gibralfaro Castle of Málaga and the castle of Antequera, and many smaller strategic hilltop forts like that of Tabernas.[6]: 212 A fortified arsenal (dar as-sina'a) was also built in Malaga, which served as a Nasrid naval base.[1]: 323 This late period saw the construction of massive towers and keeps which likely reflected a growing influence of Christian military architecture. The Calahorra Tower (now known as the Torre de Homenaje) of the Moorish Castle in Gibraltar is one particular example of this, built by the Marinids in the 14th century.[6]: 212 [1]: 322

In the Maghreb

Some of the oldest surviving Islamic-era monuments in the Maghreb are military structures in Ifriqiya and present-day Tunisia. The best-known examples are the Ribat of Sousse and the Ribat of Monastir, both dating generally from the Aghlabid period in the 9th century. A ribat was a type of residential fortress which was built to guard the early frontiers of Muslim territory in North Africa, including the coastline. They were built at intervals along the coastline so that they could signal each other from afar. Especially in later periods, ribats also served as a kind of spiritual retreat, and the examples in Sousse and Monastir both contained prayer rooms that acted as mosques. Also dating from the same period are the city walls of Sousse and Sfax, both made in stone and bearing similarities to earlier Byzantine-Roman walls in Africa.[1]: 29–36 [2]: 25–27

After the Aghlabids came the Fatimids, who took over Ifriqiya in the early 10th century. Most notably, the Fatimids built a heavily-fortified new capital at Mahdia, located on a narrow peninsula extending from the coastline into the sea. The narrow land approach to the peninsula was protected by an extremely thick stone wall reinforced with square bastions and a round polygonal tower at either end where the wall met the sea. The only gate was the

The Hammadids, who started out as governors as governors of the

Starting with the Almoravid and Almohad domination of the 11th–13th centuries, most medieval fortifications in the western Maghreb shared many characteristics with those of Al-Andalus.

After the Almohads, the Marinids followed in a similar tradition, again building mostly in rammed earth. Their most significant fortification system was the 13th-century double walls of

In Morocco, the term "Kasbah" (

Examples by country

The following is a list of important or well-known monuments and sites of historic Moorish architecture. Many are located in Europe in the Iberian Peninsula (in the former territories of Al-Andalus), with an especially strong concentration in southern Spain (modern-day Andalusia). There is also a high concentration of historic Moorish architecture in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. The types of monuments that have been preserved vary greatly between regions and between periods. For example, the historic palaces of North Africa have rarely been preserved whereas Spain retains multiple major examples of Islamic palace architecture that have are among the best-studied in the world. By contrast, few major mosques from later periods have been preserved in Spain, whereas many historic mosques are still standing and still being used in North Africa.[2]: 12–13 [13]: xvii–xviii

Spain

Major monuments

Caliphate of Córdoba (929–1031):

- Great Mosque of Cordoba

- Alcazar of the Caliphs (no longer extant)

- Medina Azahara

- Mosque of Cristo de la Luz in Toledo

Period of Taifas, Almoravids, and Almohads (11th–13th century):

- Aljaferia palace (second half of the 11th century) of the Banu Huddynasty in Zaragoza

- The Giralda, formerly the minaret of the Almohad Great Mosque of Seville

- Torre del Oro, an Almohad defensive tower in Seville

Nasrid Emirate of Granada (1232–1492):

- The Alhambra

- The Generalife, a country palace initially linked to the Alhambra by a covered walkway across the ravine that divides them

- Nasrid Maristan (hospital) of Granada

- Madrasa of Granada, of which only the prayer hall has been preserved, inside a later Spanish Baroque building

- Corral del Carbón, a funduq (caravanserai) of Granada (14th century)

- Alcaicería of Granada, Nasrid-era bazaar, but destroyed by fire in 19th century and rebuilt in different style)[139]

- Alcazar of Seville, mostly rebuilt under Christian rule but in Moorish style, with the help of craftsmen from Granada[2]

Other monuments

- Alicante

- Castle of Santa Bárbara

- Antequera

- Alhama de Granada

- Arab baths of Alhama de Granada[140]

- Almería

- Archez

- Bobastro (archaeological site and former 9th-century fortress)[6]: 48

- Badajoz

- Baños de la Encina

- Burgalimar Castle (Umayyad-era castle built in 967)[127][145]

- Córdoba

- Caliphal Baths

- Calahorra Tower

- Noria of Albolafia

- Synagogue

- "Minaret of San Juan" (930), once belonging to a mosque, now attached to the Church of San Juan de los Caballeros[146][147]

- Gormaz

- Gormaz Castle (10th-century castle, with later modifications)[148]

- Granada

- Albayzín quarter

- El Bañuelo (Arab Baths)

- Dar al-Horra Palace

- City walls and gates (remains from Zirid and Nasrid periods)[149]

- Zirid minaret at the Church of San José (ca. 1055)[150][1]

- Almohad minaret at the Church of San Juan de los Reyes[151][6]: 112, 212

- Casa de Zafra[152]

- Remains of the courtyard and minaret of the former congregational mosque of the Albaicín, at the Church of San Salvador[153][88]: 100

- Cuarto Real de Santo Domingo[154]

- Alcázar Genil and nearby ribat (rábita) converted into the Hermitage of San Sebastián[155]

- Albayzín quarter

- Fiñana

- Jaén

- Arab Baths of Jaén

- Saint Catalina's Castle

Vaulted and pierced ceiling of the Arab Baths in the Alcázar of Jerez de la Frontera (11th century)

- Jerez de la Frontera

- Alcazar

Arches and carved arabesques in a palace at the Alcazaba of Malaga, dating from the Taifa period in the 11th century[6]

- Alcazar

- Málaga

- Alcazaba

- Gibralfaro Castle

- Mérida

- Murcia

- Castillejo de Monteagudo

- Remains of 12th-century al-Qasr al-Seghir (Alcázar Seguir), in the present-day Monastery of Santa Clara

- Remains of mihrab of the former mosque of the main citadel (Alcázar Mayor), now kept at the Museum of the Church of San Juan de Dios[157]

- Niebla

- Ronda

- Arab baths of Ronda[158][124][6]: 212

- Remains of mihrab of former main mosque at the Cathedral of Ronda[6]: 212

- Seville

- Walls of Seville

- Buhaira Gardens (former Almohad palace and garden)

- Church of San Salvador (preserving traces of the former Mosque of Ibn Adabbas on this site, the first city's first great mosque)[159][2]: 21

- Tarifa

- Toledo

- Puerta de Bisagra

- Puerta de Alcántara

- Mosque of las Tornerías

- Church of San Román (Mudéjar architecture)

- Synagogue of Santa Maria la Blanca (Mudéjar architecture)

- Synagogue del Tránsito (Mudéjar architecture)

- Trujillo

Portugal

- Albufeira

- Paderne Castle

- Silves

- Silves Castle

- Mértola

- Igreja de Nossa Senhora da Anunciação(former mosque)

- Lisbon

- Castle of São Jorge (almost entirely rebuilt after the Portuguese conquest; only some archeological remains[162] and a small part of the northern wall are preserved from the Islamic period[163])

- Sintra

Morocco

- Fez (also spelled "Fes")

- Fes el-Bali ("Old Fes", founded at beginning of 9th century)

- Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque

- Mosque of the Andalusians

- City walls and gates

- Madrasa as-Saffarin

- Madrasa as-Sahrij

- Madrasa al-Attarin

- Chrabliyine Mosque

- Bab Guissa Mosque

- Mosque of Abu al-Hasan

- Madrasa Bou Inania

- Zawiya of Moulay Idris II

- Cherratine Madrasa

- Funduq al-Najjarin

- Bab Bou Jeloud (20th-century gate in local Neo-Moorish style)

- Fes el-Jdid ("New Fes", founded in 13th century)

- Dar al-Makhzen(the Royal Palace; interior not accessible to general visitors)

- Great Mosque of Fes el-Jdid

- Lalla az-Zhar Mosque

- Al-Hamra Mosque

- Marinid Royal Gardens (no longer extant)

- Fes el-Bali ("Old Fes", founded at beginning of 9th century)

- Marrakesh

- Tin Mal Mosque (at the village of Tinmel)

Courtyard of the Marinid Madrasa of Abu al-Hasan in Salé (1341) - Rabat & Salé

- Meknes

- Great Mosque of Meknes

- Bou Inania Madrasa

- Kasbah of Moulay Ismail (encompassing many structures in various states of preservation)

- Bab al-Mansour

- Mausoleum of Moulay Ismail

- Taza

- Tangier

- Great Mosque of Tangier

- Kasbah Mosque

- Tétouan (city developed and expanded by refugees from al-Andalus after the fall of Granada in 1492)[65]

- Chefchaouen

Algeria

- Algiers

- Great Mosque of Algiers

- Sidi Ramdane Mosque

- Mausoleum of Sidi Abderrahmane Et-Thaalibi

- Zawiya of Sidi M'hamed Bou Qobrine

- Al-Ummah Mosque

- New Mosque of Algiers (mix of Ottoman, European, and Moorish influences)[2]

- Tlemcen (and nearby)

- Great Mosque of Tlemcen

- Mosque of Sidi Bel Hasan

- El Mechouar Mosque

- El Mechouar Palace

- Mosque of Sidi Bu Madyan

- Mosque of al-Mansourah

- Sidi el-Haloui Mosque

- Madrasa Tashfiniya(destroyed by the French in 1876)

- Minaret of Agadir

- Bab Zir Mosque

- Béjaïa

- Nedroma

- Oran

- Imam el-Houari Mosque

- Bey Mohamed el-Kebir Mosque

- Hassan Pasha Mosque (mix of Ottoman and Moorish styles)

- Qal'at (Citadel) of the Banu Hammad (ruins in the countryside near M'Sila)

Tunisia

- Tunis

- Great Mosque of al-Zaytuna

- Kasbah Mosque

- Al-Hawa Mosque

- Al-Haliq Mosque

- Zawiya of Sidi Qasim al-Jalizi (or Sidi Qacem al-Zelliji)

- Dar Uthman

- Madrasa Slimaniya

- Madrasa al-Bashiya

- Al-Ksar Mosque

- Hammuda Pasha Mosque (local blend of Ottoman and Moorish/Tunisian styles)[2]

- Kairouan

- Great Mosque of Kairouan

- Mosque of Ibn Khayrun (Mosque of the Three Doors)

- Aghlabid Reservoirs

- Zawiya of Abu al-Balawi(Mosque of the Barber)

- Sousse

- Monastir

- Sfax

- Testour

See also

- Islamic influences on Western art

- Mudéjar Architecture of Aragon

- List of former mosques in Spain

- List of former mosques in Portugal

- Moorish Mosque, Kapurthala

References

Notes

- ^ It was replaced by the present-day Church of San Salvador. Today, only the lower part of the mosque's minaret survives, as part of the church's bell tower. The minaret is likely of a later date than the mosque's foundation, but it existed before 1079, as records show it was repaired by al-Mu'tamid (ruler of Seville) after the earthquake of that year.[25]: 145

- ^ His claims were controversial and some French archeologists rejected his findings. In 1956 the excavations were ended and the remains re-buried under the courtyard.[27]

- ^ This date has been interpreted by some as the foundation date of the whole ribat rather than the construction date of its tower.[2]: 25–26

Citations