Morrie Turner

| Morrie Turner | |

|---|---|

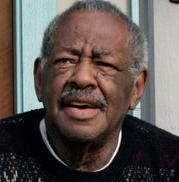

Turner in 2005 | |

| Born | Morris Nolton Turner December 11, 1923 Oakland, California |

| Died | January 25, 2014 (aged 90) Sacramento, California |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) | Cartoonist |

Notable works | Wee Pals |

| Awards | full list |

Morris Nolton Turner[1] (December 11, 1923 – January 25, 2014)[2] was an American cartoonist. He was creator of the strip Wee Pals, the first American syndicated strip with a racially integrated cast of characters.

Biography

Turner was raised in Oakland, California, the youngest child of a Pullman porter father and a homemaker and nurse mother.[1][2] He attended Cole Elementary School and McClymonds High School in Oakland and Berkeley High School.[3][4]

Turner first started drawing at age 10, drawing what he heard while listening to radio shows. He later moved onto cartoons during high school, ultimately deciding at the age of 14 that he wanted to become a professional cartoonist.[5] During this time, he also worked on the school newspaper, and was elected to the student council, though widespread racism greatly hindered any benefits he gained as a result.[6] Turner got his first training in cartooning via a correspondence course.[7] During World War II, where he served as a mechanic with Tuskegee Airmen,[1] his illustrations appeared in the newspaper Stars and Stripes. After the war, while working for the Oakland Police Department, he created the comic strip Baker's Helper.[8]

In 1963, Turner joined the Association of California Cartoonists and Gag Artists, where he befriended fellow cartoonists

This thought of a comic based on the experience of a minority would be further solidified during a discussion with Schulz. Turner lamented the lack of minorities in cartoons, and Schulz suggested he create one.

In 1969, Morris and his wife, Letha, collaborated to add a new segment to accompany Wee Pals. Titled "Soul Corner", the segment highlighted famous ethnic minorities, with Morris illustrating, and Letha researching the subjects.[13]

In 1970, Turner became a co-chairman of the White House Conference on Children and Youth.[2]

Turner appeared twice as a guest on

As the comic strip continued, Turner added characters of more ethnicities, as well as child with physical disabilities.

During the

For concerts by the Bay Area Little Symphony of Oakland, California, Turner drew pictures to the music and of children in the audience.[15]

Turner launched the first in a series of Summer Art exhibitions at the East Oakland Youth Development Center (EOYDC) on June 10, 1995.[16]

Personal life

Turner married Letha Mae Harvey on April 6, 1946; they collaborated on "Soul Corner," the weekly supplement to Wee Pals.[8] Morrie and Letha had one son, Morrie Jr;[17] Letha died in 1994. Late in life, Turner's companion was Karol Trachtenburg of Sacramento.[12] Turner died on January 25, 2014, at age 90 from chronic kidney disease in a hospital in Sacramento.[18][19]

Tributes

In 1967, Keane created the Family Circus character Morrie, a playmate of Billy and the only recurring black character in the strip, based on Turner.[20]

Awards

In 2003, the National Cartoonists Society recognized Turner for his work on Wee Pals and others with the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award.[1]

Throughout his career, Turner was showered with awards and community distinctions. For example, he received the Brotherhood Award from the

In 2000, the

Turner was honored a number of times at the San Diego Comic-Con: in 1981, he was given an Inkpot Award; and in 2012 he was given the Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award.

Bibliography

Wee Pals collections

- Wee Pals That "Kid Power" Gang in Rainbow Power (Signet Books, 1968)

- Wee Pals (Signet Books, 1969) — introduction by Charles M. Schulz

- Kid Power (Signet Books, 1970)

- Nipper (Westminster Press, 1971)

- Nipper's Secret Power (Westminster Press, 1971) ISBN 978-0-664-32498-8

- Wee Pals: Rainbow Power (Signet Books, 1973)

- Wee Pals: Doing Their Thing (Signet Books, 1973)

- Wee Pals' Nipper and Nipper's Secret Power (Signet Books, 1974)

- Wee Pals: Book of Knowledge (Signet Books, 1974) ISBN 0451058003

- Wee Pals: Staying Cool (Signet Books, 1974) ISBN 0451060768

- Wee Pals: Funky Tales (New American Library, 1975)

- Wee Pals: Welcome to the Club (Rainbow Power Club Books, 1978)

- Choosing a Health Career: Featuring Wee Pals, the Kid Power Gang (Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Health Resources Administration, 1979)

- Wee Pals: A Full-Length Musical Comedy for Children or Young Teenagers (The Dramatic Publishing Company, 1981)

- Wee Pals Make Friends with Music and Musical Instruments: Coloring Book (Stockton Symphony Association, 1982)

- Wee Pals, the Kid Power Gang: Thinking Well (Ingham County Health Department, 1983)

- Wee Pals Doing the Right Thing Coloring Book (Oakland Police Department, 1991)

- Explore Black History with Wee Pals (Just us Books, 1998) ISBN 0940975793

- The Kid Power Gang Salutes African-Americans in the Military Past and Present (Conway B. Jones Jr., 2000)

Willis and his Friends

- Ser un Hombre (Lear Siegler/Fearon Publishers, 1972) ISBN 0822474271

- Prejudice (Fearon, 1972) ASIN B00071EIOG

- The Vandals (Fearon, 1974) ASIN B0006WJ9JU

Other books

- A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Freedom (Ross Simmons, 1967)

- Black and White Coloring Book (Troubadour Press, 1969) — written with Letha Turner

- Right On (Signet Books, 1969)

- Getting It All Together (Signet Books, 1972)

- Where's Herbie? A Sickle Cell Anemia Story and Coloring Book (Sickle Cell Anemia Workshop, 1972)

- Famous Black Americans (Judson Press, 1973) ISBN 0817005919

- Happy Birthday America (Signet Book, 1975)

- All God's Chillun Got Soul (Judson Press, 1980) ISBN 0817008926

- Thinking Well (Wisconsin Clearing House, 1983)

- Black History Trivia: Quiz and Game Book (News America Syndicate, 1986)

- What About Gangs? Just Say No! (Oakland Police Department, 1994)

- Babcock (Scholastic, 1996) — by John Cottonwood and Morrie Turner, ISBN 059022221X

- Mom Come Quick (Wright Pub Co., 1997) — by Joy Crawford and Morrie Turner, ISBN 0965236838

- Super Sistahs: Featuring the Accomplishments of African-American Women Past and Present (Bye Publishing Services, 2005), ISBN 0965673952

References

- ^ a b c d e Cavna, Michael (January 31, 2014). "RIP, Morrie Turner: Cartoonists say farewell to a friend, a hero, a 'Wee Pals' pioneer". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ a b c Bernstein, Adam (January 28, 2014). "Morrie Turner dies at 90; pioneering 'Wee Pals' cartoonist". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ Hartlaub, Peter (January 28, 2014). "Morrie Turner – pioneering Wee Pals cartoonist – dies". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ "Morrie Turner". The HistoryMakers. April 6, 2004. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ^ "Celebrating the Life of Morrie Turner on the Anniversary of Wee Pals". oaklandlibrary.org. February 22, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ Kelly, Kate (February 2, 2015). "Morrie Turner: Creator of Wee Pals Comic Strip". America Comes Alive. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "California's cartooning cop". Ebony. Vol. 16, no. 12. October 1961. pp. 74–79 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lambiek Comiclopedia. April 3, 2015. Archived from the originalon January 27, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "Morrie Turner". BlacklistedCulture.com. December 15, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "Morrie Turner: Pioneering 'Wee Pals' cartoonist, dies at 90". East Bay Times. Walnut Creek, California. January 27, 2014. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018.

- ^ Hamlin, Jesse (September 13, 2009). "Wee Pals retrospective at S.F. library". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ a b c d "About Morrie Turner". Creators Syndicate. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "Celebrating the Life of Morrie Turner on the Anniversary of Wee Pals". oaklandlibrary.org. February 22, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "Kid Power Cartoon". The Museum Of UnCut Funk. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ Gibson, Michael P. "Morrie Turner". Bay Area Little Symphony. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "EOYDC: A Beacon for Oakland Youth". Alameda Magazine. July–August 2009. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ Jay, Alex (October 25, 2011). "Ink-Slinger Profiles: Morrie Turner". Stripper's Guide. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- Mercury News. Archivedfrom the original on January 27, 2014.

- Mercury News. Archivedfrom the original on January 27, 2014.

- ^ Chang, Jeff (November–December 2009). "Morrie Turner and the Kids". The Believer. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ Turner, Morrie. Who's Who of American Comic Books, 1928–1999. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

External links

- Morrie Turner at IMDb

- "Morrie Turner Collection: A description of the collection at Syracuse University". Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University. Archived from the original on March 21, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- Harvey, R.C. (February 10, 2014). "Morrie Turner: To Say the Name Is Both Eulogy and Tribute". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- Oral History Interview with Morrie Turner. Via Internet Archive, from the African American Museum and Library at Oakland.

- Finding Aid for the Morrie Turner Papers, African American Museum and Library at Oakland.