Bengal Subah

Bengal Province Bengal Subāh | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1576–1803 | |||||||||||||||

|

Flags

| |||||||||||||||

Map of the Bengal Subah in 1776 | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Subah (province) of Mughal Empire (1576–1765)

| ||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||||

| 1571–1611 | |||||||||||||||

• Establishment of Jahangirnagar | 1608 | ||||||||||||||

• de facto independence from Mughal Empire | 1717 | ||||||||||||||

| 1741–1751 | |||||||||||||||

| 1757 | |||||||||||||||

| 1764 | |||||||||||||||

• Grant of revenue to Company | 1765 | ||||||||||||||

• Grant of judiciary to Company | 1793 | ||||||||||||||

• Accession to Bengal Presidency | 1803 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Taka | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

| History of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

|

|

|

| History of India |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

The Bengal Subah, also referred to as Mughal Bengal, was the largest

Bengal Subah has been variously described the "Paradise of Nations"

By the 18th century, Bengal emerged as a semi-independent state, under the rule of the Nawabs of Bengal, who acted on Mughal sovereignty. It started to undergo

History

Mughal Empire

Bengal's physical features gave it such a fertile soil, and a favourable climate that it became a terminus of a continent-wide process of Turko-Mongol conquest and migration, informs Prof. Richard Eaton.[17]

The Mughal absorption of Bengal began during the reign of the first Mughal emperor Babur. In 1529, Babur defeated Sultan Nasiruddin Nasrat Shah of the Bengal Sultanate during the Battle of Ghaghra. Babur later annexed parts of Bengal. His son and successor Humayun occupied the Bengali capital Gaur, where he stayed for six months.[18] Humayun was later forced to seek in refuge in Persia because of Sher Shah Suri's conquests. Sher Shah Suri briefly interrupted the reigns of both the Mughals and the Bengal Sultans.

The Mughal conquest of Bengal began with the victory of Akbar's army over Sultan of Bengal

Many of the chiefs subjugated by the Mughals, some of the

The Mughal conquest of

Between 1576 and 1717, Bengal was ruled by a Mughal

Independent Nawabs of Bengal

The Nawab of Bengal

The

The British company eventually rivaled the authority of the Nawabs. In the aftermath of the

.The Nawabs of Bengal entered into treaties with numerous European colonial powers, including joint-stock companies representing

Maratha rule

The resurgent Maratha Empire launched raids against Bengal in the 18th century, which further added to the decline of the Nawabs of Bengal. A decade of Maratha conquest of Bengal from the 1740s to early 1750s forced the Nawab of Bengal to pay Rs. 1.2 million of tribute annually as the chauth of Bengal and Bihar to the Marathas, and the Marathas agreed not to invade Bengal again

The expeditions, led by

British colonization

By the late-18th century, the British East India Company emerged as the foremost military power in the region, defeating the French-allied

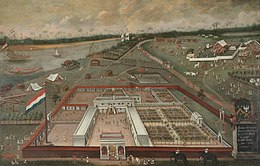

Other European powers also carved out small colonies on the territory of Bengal, including the Dutch East India Company's

Military campaigns

According to

| Conflict | Year(s) | Leader(s) | Enemy | Rival leader(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Tukaroi | 1575 | Akbar | Bengal Sultanate | Daud Khan Karrani | Mughal victory |

Battle of Raj Mahal |

1576 | Khan Jahan I | Bengal Sultanate | Daud Khan Karrani | Mughal victory |

| Conquest of Bhati | 1576–1611 |

|

Baro-Bhuyan |

|

Mughal victory |

Ahom-Mughal conflicts |

1615–1682 | Ahom kingdom | Ahom kings | Assamese victory[41] | |

Mughal-Arakan War |

1665–66 | Shaista Khan | Kingdom of Mrauk U | Thiri Thudhamma | Mughal victory |

| Battle of Plassey | 1757 | Siraj-ud-Daulah |

British Empire | Robert Clive | British victory |

-

Daud Khan receives a robe from Munim Khan

-

Battle of Chittagong in 1666 between the Mughals and Arakanese

Architecture

In rural hinterlands, the indigenous Bengali Islamic style continued to flourish, blended with Mughal elements. One of the finest examples of this style is the Atiya Mosque in Tangail (1609).[44] Several masterpieces of terracotta Hindu temple architecture were also created during this period. Notable examples include the Kantajew Temple (1704) and the temples of Bishnupur (1600–1729).

Art

An authentic Bengali art was reflected in the

A provincial Bengali style of Mughal painting flourished in Murshidabad during the 18th century. Scroll painting and ivory sculptures were also prevalent.

-

Murshidabad-style painting of a woman playing a rudra veena

-

Scroll painting of aGhaziriding a Bengal tiger

Demographics

Population

Bengal's population is estimated to have been 30 million prior to the Great Bengal famine of 1770, which reduced it by as much as a third.[46]

Religion

Bengal was an affluent province with a

Immigration

There was a significant influx of migrants from the

Economy and trade

The Bengal Subah had the largest regional economy in that period. It was described as the paradise of nations.[

Parthasarathi estimates that grain wages for weaving and spinning in Bengal and Britain were comparable in the mid 18th century.[52] However, due to the scarcity of data, more research is needed before drawing any conclusions.[53]

Bengal had many traders and bankers. Among them was the

Agrarian reform

The Mughals launched a vast economic development project in the

There are sparse accounts of the Bengal revenue administration in Abul Fazl's Ain-i-Akbari and some in Mirza Nathan's Baharistan-i-Ghaibi.[55] According to the former,

The demands of each year are paid by instalments in eight months, they (the ryots) themselves bringing mohurs and rupees to the appointed place for the receipt of revenue, as the division of grain between the government and the husbandman is not here customary. The harvests are always abundant, measurement is not insisted upon, and the revenue demands are determined by estimate of the crop.[55]

In contrast, the Baharistan says there were two collections per year, following the spring and autumn harvests. It also says that, at least in some areas, revenue demands were based on survey and land measurement.[55]

Bengali peasants were quick to adapt to profitable new crops between 1600 and 1650.

The increased agricultural productivity led to lower food prices. In turn, this benefited the Indian textile industry. Compared to Britain, the price of grain was about one-half in South India and one-third in Bengal, in terms of silver coinage. This resulted in lower silver coin prices for Indian textiles, giving them a price advantage in global markets.[57]

Industrial economy

In the 17th century, Bengal was an affluent province that was, according to economic historian Indrajit Ray, globally prominent in industries such as

Many historians have built on the perspective of

Textile industry

Bengal was a centre of the worldwide muslin, jute and silk trades. During this era, the most important center of jute and cotton production was Bengal, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka, leading to muslin being called "daka" in distant markets such as Central Asia.[60] Domestically, much of India depended on Bengali products such as rice, silks and cotton textiles. Overseas, Europeans depended on Bengali products such as cotton textiles, silks and opium; Bengal accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia, for example, including more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks.[8] From Bengal, saltpetre was also shipped to Europe, opium was sold in Indonesia, raw silk was exported to Japan and the Netherlands, and cotton and silk textiles were exported to Europe, Indonesia and Japan.[61] The jute trade was also a significant factor.

Shipbuilding industry

Bengal had a large shipbuilding industry. Indrajit Ray estimates shipbuilding output of Bengal during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries at 223,250 tons annually, compared with 23,061 tons produced in nineteen colonies in North America from 1769 to 1771.[62] He also assesses ship repairing as very advanced in Bengal.[62]

An important innovation in shipbuilding was the introduction of a

Administrative divisions

In the revenue settlement by

Initially the capital of the Subah was Tanda.[citation needed] On 9 November 1595, the foundations of a new capital were laid at Rajmahal by Man Singh I who renamed it Akbarnagar.[65] In 1610 the capital was shifted from Rajmahal to Dhaka[66] and it was renamed Jahangirnagar. In 1639, Shah Shuja again shifted the capital to Rajmahal. In 1660, Muazzam Khan (Mir Jumla) again shifted the capital to Dhaka. In 1703, Murshid Quli Khan, then diwan (prime minister in charge of finance) of Bengal shifted his office from Dhaka to Maqsudabad and later renamed it Murshidabad.[citation needed]

In 1656, Shah Shuja reorganised the sarkars and added Orissa to the Bengal Subah.[citation needed]

The sarkars (districts) and the parganas/mahallahs (tehsils) of Bengal Subah were:[64]

| Sarkar | Pargana |

|---|---|

| Udamabar/Tanda (modern-day areas include North Birbhum, Rajmahal and Murshidabad) | 52 parganas |

Jannatabad (Lakhnauti) (Modern day Malda division ) |

66 parganas |

Fatehabad |

31 parganas |

| Mahmudabad (modern-day areas include Jessore ) |

88 parganas |

| Khalifatabad | 35 parganas |

| Bakla | 4 parganas |

| Purniyah | 9 parganas |

| Tajpur (East Dinajpur) | 29 parganas |

| Ghoraghat (South Rangpur Division, Bogura) | 84 parganas |

Pinjarah |

21 parganas |

| Barbakabad (West Dinajpur ) |

38 parganas |

| Bazuha | 32 parganas |

| Sonargaon modern day Dhaka Division | 52 parganas |

Srihatta |

8 mahals |

| Chittagong | 7 parganas |

Sharifatabad |

26 parganas |

Sulaimanabad |

31 parganas |

Howrah District ) |

53 parganas |

| Mandaran | 16 parganas |

Sarkars of Orissa:

| Sarkar | Mahal |

|---|---|

Jaleswar |

28 |

Bhadrak |

7 |

| Kotok ( Cuttack ) |

21 |

| Kaling Dandpat | 27 |

| Raj Mahendrih | 16 |

Government

The state government was headed by a

In 1717, the Mughal government replaced Viceroy

List of Subadars & Nawab Nazims

Subahdars

| Personal name[69] | Reign | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Munim Khan Khan-i-Khanan منعم خان، خان خاناں |

25 September 1574 – 23 October 1575 | ||

Hussain Quli Beg Khan Jahan Iحسین قلی بیگ، خان جہاں اول |

15 November 1575 – 19 December 1578 | ||

| Muzaffar Khan Turbati مظفر خان تربتی |

1579–1580 | ||

| Mirza Aziz Koka Azam Khan I میرزا عزیز کوکہ،خان اعظم |

1582–1583 | ||

| Shahbaz Khan Kamboh Lahori Mir Jumla I شھباز خان کمبوہ |

1583–1585 | ||

| Sadiq Khan صادق خان |

1585–1586 | ||

| Wazir Khan Tajik وزیر خان |

1586–1587 | ||

| Sa'id Khan سعید خان |

1587–1594 | ||

| Raja Man Singh I راجہ مان سنگھ |

4 June 1594 – 2 September 1606 | ||

| Qutb-ud-din Khan Koka قطب الدین خان کوکہ |

2 September 1606 – 20 May 1607 | ||

| Jahangir Quli Beg جہانگیر قلی بیگ |

1607–1608 | ||

| Sheikh Ala-ud-din Chisti Islam Khan I اسلام خان چشتی |

June 1608 – 1613 | ||

| Qasim Khan Chishti Muhtashim Khan قاسم خان چشتی |

1613–1617 | ||

| Ibrahim Khan Fateh Jang Ibrahim Khan I ابراہیم خان فتح جنگ |

1617–1622 | ||

| Mahabat Khan محابت خان |

1622–1626 | ||

| Mirza Amanullah Khan Jahan II میرزا أمان اللہ ، خان زماں ثانی |

1626 | ||

Mukarram Khan Chishti مکرم خان |

1626–1627 | ||

| Fidai Khan I فدای خان |

1627–1628 | ||

| Qasim Khan Juvayni Qasim Manija قاسم خان جوینی، قاسم مانیجہ |

1628–1632 | ||

| Mir Muhammad Baqir Azam Khan II میر محمد باقر، اعظم خان |

1632–1635 | ||

| Mir Abdus Salam Islam Khan II اسلام خان مشھدی |

1635–1639 | ||

| Sultan Shah Shuja شاہ شجاع |

1639–1660 | ||

| Mir Jumla II میر جملہ |

May 1660 – 30 March 1663 | ||

| Mirza Abu Talib Shaista Khan I میرزا ابو طالب، شایستہ خان |

March 1664 – 1676 | ||

| Fidai Khan Koka, Fidai Khan II اعظم خان کوکہ، فدای خان ثانی |

1676–1677 | ||

| Sultan Muhammad Azam Shah Alijah محمد اعظم شاہ عالی جاہ |

1678–1679 | ||

| Mirza Abu Talib Shaista Khan I میرزا ابو طالب، شایستہ خان |

1680–1688 | ||

| Ibrahim Khan ibn Ali Mardan Khan Ibrahim Khan II ابراہیم خان ابن علی مردان خان |

1688–1697 | ||

| Sultan Azim-us-Shan عظیم الشان |

1697–1712 | ||

| Others were appointed but did not show up from 1712 to 1717 and managed by Deputy Subahdar Murshid Quli Khan. | |||

| Murshid Quli Khan مرشد قلی خان |

1717–1727 | ||

Nawab Nazims (independent)

| Portrait | Regnal name | Personal name | Birth | Reign | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasiri dynasty | |||||

|

Jaafar Khan Bahadur Nasiri | Murshid Quli Khan | 1665 | 1717– 1727 | 30 June 1727 |

|

Ala-ud-Din Haidar Jang | Sarfaraz Khan Bahadur Dakhni | ? | 1727–1727 | 29 April 1740 |

|

Shuja ud-Daula | Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan or Mirza Deccani | Around 1670 (date not available) | July 1727 – 26 August 1739 | 26 August 1739 |

|

Ala-ud-Din Haidar Jang | Sarfaraz Khan Bahadur Dakhni | ? | 13 March 1739 – April 1740 | 29 April 1740 |

| Afsar dynasty | |||||

|

Hashim ud-Daula | Muhammad Alivardi Khan Bahadur | Before 10 May 1671 | 29 April 1740 – 9 April 1756 | 9 April 1756 |

|

Siraj ud-Daulah | Muhammad Siraj-ud-Daulah | 1733 | April 1756 – 2 June 1757 | 2 July 1757 |

References

- OL 30677644M. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Rajmahal – India". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ "Dhaka – national capital, Bangladesh". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Rizvi, Saiyid Athar Abbas (1986). A Socio-intellectual History of the Isnā 'Asharī Shī'īs in India: 16th to 19th century A.D. Vol. 2. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. pp. 45–47.

- ISBN 978-0-19-061320-4.

- ^ Steel, Tim (19 December 2014). "The paradise of nations". Op-ed. Dhaka Tribune. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ISBN 978-984-512-337-2.

- ^ a b Om Prakash (2006). "Empire, Mughal". In John J. McCusker (ed.). History of World Trade Since 1450. World History in Context. Vol. 1. Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 237–240. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1. Archivedfrom the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Khandker, Hissam (31 July 2015). "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star (Op-ed). Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-1-317-13522-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-516520-3. Archivedfrom the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1. Archivedfrom the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ a b Shombit Sengupta (8 February 2010). "Bengal's plunder gifted the British Industrial Revolution". The Financial Express. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ The Bengalis. p. 143.

- ISBN 0-520-20507-3.

- ^ "Humayun". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- OCLC 5585437.

- OCLC 5585437.

- OCLC 5585437.

- ^ "Dhaka". Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 July 2016. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Sir Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler (1953). The Cambridge History of India: The Indus civilization. Vol. Supplementary. Cambridge University Publishers. pp. 237–.

- ISBN 978-984-464-164-8.

- ISBN 978-81-317-3202-1.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-8024-5.

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/63552. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ "ʿAlī Vardī Khān | nawab of Bengal". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "Bengal | region, Asia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "Odisha - History". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ Silliman, Jael (28 December 2017). "Murshidabad can teach the rest of India how to restore heritage and market the past". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ISBN 978-81-207-2506-5.

- ISBN 978-1-63557-395-4.

- ^ "Forgotten Indian history: The brutal Maratha invasions of Bengal". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-14-341678-4.

- ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6.

- ISBN 978-81-250-1149-1.

- OCLC 43324741.

- ^ Tim Steel (31 October 2014). "Gunpowder plots". Dhaka Tribune. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ "Saltpetre". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 247.

- ^ "Nimtoli Deuri becomes heritage museum". The Daily Star. 17 January 2019. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "- YouTube" ঢাকার নিমতলি দেউড়ি এখন ঐতিহ্য জাদুঘর. Nimtoli Deuri Becomes Heritage Museum. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c "The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760". University of California Press. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ "In Search of Bangladeshi Islamic Art". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-19-020988-9. Archivedfrom the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ Karim, Abdul (2012). "Iranians, The". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ Ali, Ansar; Chaudhury, Sushil; Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Armenians, The". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-4008-3138-8.

- ISBN 978-81-8069-149-2. Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-415-21489-6.

[page 136: From 1500-1850,] in Bengal the main market was Chittagong ... [page 164:] Mir Jumla, who in the 1640s had his own ships ... travelling all over the ocean: to Bengal, Surat, Arakan, Ayuthya, Aceh, Melaka, Johore, Bantam, Makassar, Ceylon, Bandar Abbas, Mocha and the Maldives.

- ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0. Archivedfrom the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0. Archivedfrom the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ OCLC 5585437.

- ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0. Archivedfrom the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ISBN 978-81-7211-201-1.

- ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- ^ Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760 Archived 4 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, page 202, University of California Press

- ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- ^ "Technological Dynamism in a Stagnant Sector: Safety at Sea during the Early Industrial Revolution" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ a b Sarkar, Jadu-Nath, ed. (1949). Ain I Akbari Of Abul Fazl-i-allami. Vol. II. Translated by Jarrett, H. S. Calcutta: Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal. pp. 142–55.

- ISBN 81-250-0333-9.

- ISBN 0-415-23988-5.

- ^ Chatterjee, Anjali (2012). "Azim-us-Shan". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Nawab". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ISBN 0-520-20507-3.

Further reading

- ISBN 978-0-19-807742-8.