Murad III

| Murad III | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ottoman Caliph Amir al-Mu'minin Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques | |||||

Life-size portrait, attributed to a Spanish artist, 17th century | |||||

| Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Padishah) | |||||

| Reign | 27 December 1574 – 16 January 1595 | ||||

| Predecessor | Selim II | ||||

| Successor | Mehmed III | ||||

| Born | 4 July 1546 Manisa, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Died | 16 January 1595 (aged 48) Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Burial | Hagia Sophia, Istanbul | ||||

| Consorts | |||||

| Issue Among others | Hümaşah Sultan Ayşe Sultan Mehmed III Şehzade Mahmud Şehzade Selim Fatma Sultan Mihrimah Sultan Fahriye Sultan | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Ottoman | ||||

| Father | Selim II | ||||

| Mother | Nurbanu Sultan | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

| Tughra |  | ||||

Murad III (

Early life

Born in Manisa on 4 July 1546,[1] Şehzade Murad was the oldest son of Şehzade Selim and his powerful wife Nurbanu Sultan. He received a good education and learned the Arabic and Persian languages. After his ceremonial circumcision in 1557, Murad's grandfather, the Sultan Suleiman I, appointed him sancakbeyi (governor) of Akşehir in 1558. At the age of 18 he was appointed sancakbeyi of Saruhan. Suleiman died in 1566 when Murad was 20, and his father became the new sultan, Selim II. Selim II broke with tradition by sending only his oldest son out of the palace to govern a province, assigning Murad to Manisa.[2]: 21–22

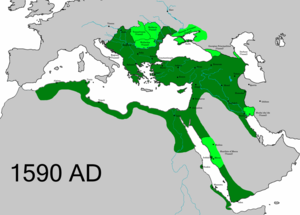

Reign

Selim died in 1574 and was succeeded by Murad, who began his reign by having his five younger brothers strangled.

Expedition to Morocco

Abd al-Malik became a trusted member of the Ottoman establishment during his exile. He made the proposition of making Morocco an Ottoman vassal in exchange for the support of Murad III in helping him gain the Saadi throne.[5]

With an army of 10,000 men, most of whom were Turks, Ramazan Pasha and Abd al-Malik left from Algiers to install Abd al-Malik as an Ottoman vassal ruler of Morocco.[6] Ramazan Pasha conquered Fez which caused the Saadi Sultan to flee to Marrakesh which was also conquered. Abd al-Malik then assumed rule over Morocco as a client of the Ottomans.[7][5][8]

Abd al-Malik made a deal with the Ottoman troops by paying them a large amount of gold and sending them back to Algiers, suggesting a looser concept of vassalage than Murad III may have thought.[5] Murad's name was recited in the Friday prayer and stamped on coinage marking the two traditional signs of sovereignty in the Islamic world.[9] The reign of Abd al-Malik is understood to be a period of Moroccan vassalage to the Ottoman Empire.[10][11] Abd al-Malik died in 1578 and was succeeded by his brother Ahmad al-Mansur who formally recognised the suzerainty of the Ottoman Sultan at the start of his reign while remaining de facto independent. He stopped minting coins in Murad's name, dropped his name from the Khutba and declared his full independence in 1582.[12][13]

War with the Safavids

The Ottomans had been at peace with the neighbouring rivaling Safavid Empire since 1555, per the

Ottoman activity in the Horn of Africa

During his reign, an Ottoman Admiral by the name of Mir Ali Beg was successful in establishing Ottoman supremacy in numerous cities in the Swahili coast between Mogadishu and Kilwa.[14] Ottoman suzerainty was recognised in Mogadishu in 1585 and Ottoman supremacy was also established in other cities such as Barawa, Mombasa, Kilifi, Pate, Lamu, and Faza.[15][16]

Financial affairs

Murad's reign was a time of financial stress for the Ottoman state. To keep up with changing military techniques, the Ottomans trained infantrymen in the use of firearms, paying them directly from the treasury. By 1580 an influx of silver from the New World had caused high inflation and social unrest, especially among Janissaries and government officials who were paid in debased currency. Deprivation from the resulting rebellions, coupled with the pressure of over-population, was especially felt in Anatolia.[2]: 24 Competition for positions within the government grew fierce, leading to bribery and corruption. Ottoman and Habsburg sources accuse Murad himself of accepting enormous bribes, including 20,000 ducats from a statesman in exchange for the governorship of Tripoli and Tunisia, thus outbidding a rival who had tried bribing the Grand Vizier.[2]: 35

During his period, excessive inflation was experienced, the value of silver money was constantly played, food prices increased. 400 dirhams should be cut from 600 dirhams of silver, while 800 was cut, which meant 100 percent inflation. For the same reason, the purchasing power of wage earners was halved, and the consequence was an uprising.[17]

English pact

Numerous envoys and letters were exchanged between

Personal life

Palace life

Following the example of his father Selim II, Murad was the second Ottoman sultan who never went on campaign during his reign, instead spending it entirely in Constantinople. During the final years of his reign, he did not even leave

In the morning he rises at dawn to say his prayer for half an hour, then for another half-hour he writes. Then he is given something pleasant as a collation, and afterwards sets himself to read for another hour. Then he begins to give audience to the members of the Divan on the four days of the week that this occurs, as had been said above. Then he goes for a walk through the garden, taking pleasure in the delight of fountains and animals for another hour, taking with him the dwarves, buffoons and others to entertain him. Then he goes back once again to studying until he considers the time for lunch has arrived. He stays at table only half an hour, and rises (to go) once again into the garden for as long as he pleases. Then he goes to say his midday prayer. Then he stops to pass the time and amuse himself with the women, and he will stay one or two hours with them, when it is time to say the evening prayer. Then he returns to his apartments or, if it pleases him more, he stays in the garden reading or passing the time until evening with the dwarfs and buffoons, and then he returns to say his prayers, that is at nightfall. Then he dines and takes more time over dinner than over lunch, making conversation until two hours after dark, until it is time for prayer [...] He never fails to observe this schedule every day.[2]: 29–30

Özgen Felek argues that Murad's sedentary lifestyle and lack of participation in military campaigns earned him the disapproval of

Children

Before becoming sultan, Murad had been loyal to Safiye Sultan, his Albanian concubine. His monogamy was disapproved of by Nurbanu Sultan, who worried that Murad needed more sons to succeed him in case Mehmed died young. She also worried about Safiye's influence over her son and the Ottoman dynasty. Five or six years after his accession to the throne, Murad was given a pair of concubines by his sister Ismihan. Upon attempting sexual intercourse with them, he proved impotent. "The arrow [of Murad], [despite] keeping with his created nature, for many times [and] for many days has been unable to reach at the target of union and pleasure," wrote Mustafa Ali. Nurbanu accused Safiye and her retainers of causing Murad's impotence with witchcraft. Several of Safiye's servants were tortured by eunuchs in order to discover a culprit. Court physicians, working under Nurbanu's orders, eventually prepared a successful cure, but a side effect was a drastic increase in sexual appetite; by the time Murad died, he was said to have fathered over a hundred children.[2]: 31–32 Nineteen of these were executed by Mehmed III when he became sultan.

Women at court

Influential ladies of his court included his mother Nurbanu Sultan, his sister Ismihan Sultan, wife of grand vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, and musahibes (favourites) mistress of the housekeeper Canfeda Hatun, mistress of financial affairs Raziye Hatun, and the poet Hubbi Hatun, Finally, after the death of his mother and older sister, Safiye Sultan was the only influential woman in the court.[20][21]

Eunuchs at court

Before Murad, the palace

Murad and the arts

Murad took great interest in the arts, particularly

Murad also furnished the content of Kitabü’l-Menamat (The Book of Dreams), addressed to Murad's spiritual advisor, Şüca Dede. A collection of first person accounts, it tells of Murad's spiritual experiences as a Sufi disciple. Compiled from thousands of letters Murad wrote describing his dream visions, it presents a hagiographic self-portrait. Murad dreams of various activities, including being stripped naked by his father and having to sit on his lap,[2]: 72 single-handedly killing 12,000 infidels in battle,[2]: 99 walking on water, ascending to heaven, and producing milk from his fingers.[2]: 143

In another letter addressed to Şüca Dede, Murad wrote "I wish that God, may He be glorified and exalted, had not created this poor servant as the descendant of the Ottomans so that I would not hear this and that, and would not worry. I wish I were of unknown pedigree. Then, I would have one single task, and could ignore the whole world."[2]: 171

The diplomatic edition of these dream letters have been recently published by Ozgen Felek in Turkish.

Death

Murad died from what is assumed to be natural causes in the Topkapı Palace on 16 January 1595 and was buried in a tomb next to the Hagia Sophia. In the mausoleum are 54 sarcophagus of the sultan, his wives and children that are also buried there. He is also responsible for changing the burial customs of the sultans' mothers. Murad had his mother Nurbanu buried next to her husband Selim II, making her the first consort to share a sultan's tomb.[2]: 33–34

Family

Consorts

Murad is believed to have had Safiye Sultan as his only concubine for circa fifteen years. However, Safiye was opposed by Murad's mother, Nurbanu Sultan, and by his sister, Ismihan Sultan, and around 1580, she was exiled to the Old Palace on charges of having rendered the sultan impotent with a spell, after he had not succeeded or had not wanted to have sex with two concubines received by his sister. Furthermore, Nurbanu was concerned about the future of the dynasty, as she believed that Safiye's son alone, Mehmed, (two of three sons that Safiye give to Murad were dead before 1580) were not enough to ensure the succession. After Safiye's exile, revoked only after Nurbanu's death on December 1583, Murad, to deny the rumor about his impotency, took a huge number of concubines and he had more than fifty known children, although according to sources the total number could exceed hundred.[26]

At time of his death in 1595, Murad had at least thirty-five concubines, amongs others:[27]

- Safiye Sultan, an ethnic Albanian. Haseki Sultan of Murad and Valide sultan of Mehmed III;[28]

- Şemsiruhsar Hatun, mother of Rukiye Sultan. She commissioned Koranic readings of prayers in the

- Mihriban Hatun;[27]

- Şahıhuban Hatun; she commissioned a school in Fatih, where she is buried[27]

- Nazperver Hatun; she commissioned a mosque in Eyüp[27]

- Zerefşan Hatun[27]

- Fakriye Hatun[29]

- A concubine who died in stillbirth in August 1591, along with their son, and were interred together.[30]

- Seven of pregnant concubines were placed in sacks and tossed into the Sea of Marmara, where they drowned, in 1595, by order of Mehmed III.[31]

- A concubine seduced and made pregnant by Mehmed III when he was a prince. The act was a violation of the rules of the harem, so Mehmed’s grandmother, Nurbanu Sultan, ordered the girl to be drowned in order to protect her grandson.

After the death of Murad III many of his concubines who became childless when at his accession Mehmed had his half-brothers killed, and others who never had children by Sultan, were remarried off to palace officials, such as door keepers, cavalry forces (bölük halkı), and sergeants (çavus).[32][33]

Sons

Murad III had at least 27 known sons.

On Murad's death in 1595 Mehmed III, his eldest son and new sultan, son of Safiye Sultan, executed the 19 half-brothers still alive and drowned seven pregnant concubines, fulfilling the Law of Fraticide.

Known sons of Murad III are:

- Sultan Mehmed III (26 May 1566, Manisa Palace, Manisa – 22 December 1603, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Mehmed III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque, Constantinople), with Safiye Sultan, became the next sultan;

- Şehzade Selim (1567, Manisa Palace, Manisa - 25 May 1577), with Safiye Sultan.

- Şehzade Mahmud (1568, Manisa Palace, Manisa – before 1580, buried in Selim II Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque), with Safiye Sultan.

- Şehzade Fülan (June 1582, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - June 1582, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople. buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque). Stillbirth.

- Şehzade Cihangir (February 1585, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - August 1585, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque); twin of Şehzade Suleyman.

- Şehzade Suleyman (February 1585, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - 1585, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque); twin of Şehzade Cihangir.

- Şehzade Abdullah (1585, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Mustafa (1585, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Abdurrahman (1585, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Bayezid (1586, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Hasan (1586, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - died 1591, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Cihangir (1587, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Yakub (1587, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Ahmed (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - before 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Fülan (August 1591, stillbirth);

- Şehzade Alaeddin (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Davud (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Alemşah (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Ali (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Hüseyin (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Ishak (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Murad (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Osman (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - died 1587, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Yusuf (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Korkud (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Ömer (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Selim (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

In addition to these, a European braggart, Alexander of Montenegro, claimed to be the lost son of Murad III and Safiye Sultan, presenting himself with the name of Şehzade Yahya and claiming the throne for it. His claims were never proven and appear dubious to say the least.[34]

Daughters

Murad had more of thirty daughters still alive at his death in 1595, of whom nineteen died of plague (or smallpox) in 1598.[35][32]

It is not known if and how many daughters may have died before him.

Known daughters of Murad III are:

- Hümaşah Sultan (Manisa, c. 1567 - Costantinople, 1625 : 168 ); buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque) - with Safiye Sultan. Also called Hüma Sultan.[36] She married Nişar Mustafazade Mehmed Pasha (died 1586). She may have then married Serdar Ferhad Pasha (d.1595) in 1591.[37] She was lastly married in 1605 to Nakkaş Hasan Pasha (died 1622);[38][39][40][41][42]

- Ayşe Sultan (Manisa, c. 1565 - Costantinople, 15 May 1605, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque) - with Safiye Sultan. Married firstly on 20 May 1586, to Ibrahim Pasha,[39] married secondly on 5 April 1602, to Yemişçi Hasan Pasha, married thirdly on 29 June 1604, to Güzelce Mahmud Pasha.[40][43]

- Fatma Sultan (Manisa, c. 1573 - Costantinople, 1620, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque) - with Safiye Sultan. Married first on 6 December 1593, to Halil Pasha,[39][43] married second December 1604, to Cafer Pasha;[40] married third 1610 Hizir Pasha, married fourth Murad Pasha.

- Mihrimah Sultan (Costantinople, Early January 1578 - April 1621 ; buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque[44]) - possibly with Safiye Sultan;[40][45]

- Fahriye Sultan (died in 1656, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque[44]), - possibly with Safiye Sultan, perhaps born after her return from exile in Old Palace. Called also Fahri Sultan.[46][38] She married firstly to Cuhadar Ahmed Pasha, Governor of Mosul, married secondly to Sofu Bayram Pasha, Governor of Bosnia (dien in 1633);[43][47][48]: 168 , married thirtly with Deli Dilaver Pasha (died 1668).: 168 [49]

- Rukiye Sultan (buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque) - with Şemsiruhsar Hatun.[43][27][39][40][50]

- Mihriban Sultan (buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque)[43] married in 1613;[39]

- Hatice Sultan (1583 - 1648,: 168 buried in Şehzade Mosque[51]), was married in 1598 to Sokolluzade Lala Mehmed Pasha and had two sons and a daughter.[52] She participated in the reparation of the minarets of Bayezid Veli Mosque inside Kerch Fortress in 1599.[53] After widowed, in 1613 she married Gürşci Mehmed Pasha of Kefe, governor of Bosnia.[40][54][48]: 168

- Fethiye Sultan (buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque).

- Beyhan Sultan (died fl. 1648[55]), married in 1613 to Vizier Kurşuncuzade Mustafa Pasha;[40][54][48][55]: 168

- Sehime Sultan,[46] married in 1613 to Topal Mehmed Pasha, formerly a Kapucıbaşı;[40][54][39][48][55]: 168

- A daughter married to Davud Pasha;[39]

- A daughter married in 1613 to Kücük Mirahur Mehmed Agha;[40][54]

- A daughter married in 1613 to Mirahur-i Evvel Muslu Agha;[40][54]

- A daughter married in 1613 to Bostancıbaşı Hasan Agha;[40][54]

- A daughter married in 1613 to Cığalazade Mehmed Bey;[40][54]

- Nineteen daughters, died of plague in 1598;

- A daughter who died young on 29 July 1585.[56]

In fiction

- Murad is portrayed by the Romanian actor Colea Rautu in the historic epic film Michael the Brave.

- My Name is Red, 1998) takes place at the court of Murad III, during nine snowy winter days of 1591, which the writer uses in order to convey the tension between East and West. Murad is not specifically named in the book, and is referred to only as "Our Sultan".

- The Harem Midwife by Roberta Rich - a historical fiction set in Constantinople (1578) which follows Hannah, a midwife, who tends to many of the women in Sultan Murad III's harem.

- In the 2011 TV series Muhteşem Yüzyıl, Murad III is portrayed by Turkish actor Serhan Onat.

References

- ^ "Murad III". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Felek, Özgen. (2010). Re-creating image and identity: Dreams and visions as a means of Murad III's self-fashioning. PhD Thesis. University of Michigan. Ann Arbor: ProQuest/UMI. (Publication No. 3441203).

- ^ Marriott, John Arthur. The Eastern Question (Clarendon Press, 1917), 96.

- ^ "Murad III | Ottoman sultan". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5– via Google Books.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 3 - J. D. Fage: Pg 408

- ^ هيسبريس تمودا Volume 29, Issue 1 Editions techniques nord-africaines, 1991

- ISBN 978-0-226-33031-0

- ISBN 9780226388069– via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-0-226-03739-4.

- ^ "Langues et littératures". Faculté des lettres et des sciences humaines. 9 September 1981 – via Google Books.

- ^ Rivet, Daniel (2012). Histoire du Maroc: de Moulay Idrîs à Mohammed VI. Fayard

- ^ A Struggle for the Sahara:Idrīs ibn ‘Alī’s Embassy toAḥmad al-Manṣūr in the Context ofBorno-Morocco-Ottoman Relations, 1577-1583 Rémi Dewière Université de Paris Panthéon Sorbonne

- ISBN 9780582050693– via Google Books.

- ISBN 9780253027320– via Google Books.

- ISBN 9789047423836– via Google Books.

- ^ Sakaoğlu 2008, p. 172.

- ^ ISBN 9780674024748.

- ^ Karateke, Hakan T. "On the Tranquility and Repose of the Sultan." The Ottoman World. Ed. Christine Woodhead. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2011. p. 118.

- ISBN 978-90-04-17918-9.

- ISBN 978-90-04-10723-6.

- ^ Von Schierbrand, Wolf (28 March 1886). "Salve Sold to the Turk" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ Gamm, Niki (25 May 2013). "The black eunuchs and the Ottoman dynasty". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-8223-4869-6.

- ISBN 978-0-307-59392-4

- )

- ^ a b c d e f g Altun, Mustafa (2019). Yüzyıl Dönümünde Bir Valide Sultan: Safiye Sultan'ın Hayatı ve Eserleri. pp. 20–21.

- ^ Mustafa Çağatay Uluçay, Padışahların kadınları ve kızları, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, 1980, pp. 42-6

- ^ Alderson, A.D.; The structure of the Ottoman Dynasty

- ^ "Tarih-i Selaniki 1-2 : Selânik Mustafa Efendi, d. 1600? : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Internet Archive. 25 March 2023. p. 251. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ISBN 978-1-4766-0889-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-108-48836-5.

- ISSN 2148-6743.

- ^ Tezcan, Baki (2001). Searching For Osman: A Reassessment Of The Deposition Of Ottoman Sultan Osman II (1618-1622). pp. 327–8 n. 17.

- ISBN 978-0-549-74445-0.

- ^ Sarinay, Yusuf (2000). 82 Numaralı Mühimme Defteri'nin (H.1026-1027/1617-1618) Transkripsiyonu ve Değerlendirilmesi. T.C. Başbakanlık Devlet Arşivleri Genel Müdürlüğü. p. 7.

- ^ Sakaoğlu, Necdet (2008). Bu mülkün kadın sultanları: Vâlide sultanlar, hâtunlar, hasekiler, kadınefendiler, sultanefendiler. Oğlak Yayıncılık. p. 217.

- ^ a b Miović 2018, p. 168.

- ^ a b c d e f g Peçevi, Ibrahim; Baykal, Bekir Sıtkı (1982). Peçevi Tarih, Volume 2. Başbakanlık Matbaası. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Tezcan, Baki (2001). Searching For Osman: A Reassessment Of The Deposition Of Ottoman Sultan Osman II (1618-1622). pp. 328 n. 18.

- ^ Great Britain. Public Record Office (1900). Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts Relating to English Affairs: Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice, and in Other Libraries of Northern Italy. Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts Relating to English Affairs: Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice, and in Other Libraries of Northern Italy. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 442.

- ^ "Nakkaş Hasan Paşa". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ ISBN 978-975-437-840-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-975-19-0121-7.

- ^ Uçtum, Nejat R. Hürrem ve Mihrümah sultanların Polonya Kralı II. Zigsmund'a Yazdıkları Mektuplar. p. 707.

- ^ a b Kahya, Ozan (2011). "11 numaralı İstanbul Mahkemesi defteri (H.1073) : tahlil ve metin". pp. 219, 303–304.

- ^ Ayvansarayî, H.H.; Derin, F.Ç. (1978). Vefeyât-ı selâtîn ve meşâhı̂r-i ricâl. Yayınlar (İstanbul Üniversitesi. Edebiyat Fakültesi). Edebiyat Fakültesi Matbaası. p. 45.

- ^ a b c d Dumas, Juliette (2013). Les perles de nacre du sultanat: Les princesses ottomanes (mi-XVe – mi-XVIIIe siècle). p. 464.

- ISBN 978-3-11-096577-3.

- ISBN 978-0-521-62095-6.

- ISBN 978-975-7306-04-7.

- ^ Bayrak, 1998, p. 43.

- ^ Öztuna, 1977. Başlangıcından zamanımıza kadar Büyük Türkiye tarihi, p. 125.

- ^ ISBN 978-975-16-1585-5.

- ^ ISSN 1330-0598.

- ISSN 2148-6743.

External links

![]() Media related to Murad III at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Murad III at Wikimedia Commons

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 14–15.

- Ancestry of Sultana Nur-Banu (Cecilia Venier-Baffo)