Muscle cell

This article is missing information about type 1 versus type 2 fibres. (November 2023) |

| Muscle cell | |

|---|---|

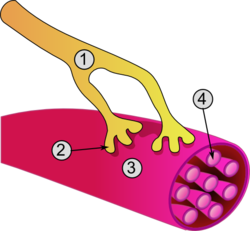

General structure of a skeletal muscle cell and neuromuscular junction: | |

| Details | |

| Location | Muscle |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | myocytus |

| MeSH | D032342 |

| TH | H2.00.05.0.00002 |

| FMA | 67328 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

A muscle cell, also known as a myocyte, is a mature contractile

Skeletal muscle cells form by

Cardiac muscle cells form the cardiac muscle in the walls of the heart chambers, and have a single central nucleus.[7] Cardiac muscle cells are joined to neighboring cells by intercalated discs, and when joined in a visible unit they are described as a cardiac muscle fiber.[8]

Smooth muscle cells control involuntary movements such as the peristalsis contractions in the esophagus and stomach. The Smooth muscle has no myofibrils or sarcomeres and is therefore non-striated. Smooth muscle cells have a single nucleus.

Structure

The unusual

Skeletal muscle cells

Skeletal muscle cells are the individual contractile cells within a muscle and are more usually known as muscle fibers because of their longer threadlike appearance.

A striated muscle fiber contains

In striations of muscle bands, myosin forms the dark filaments that make up the A band. Thin filaments of actin are the light filaments that make up the I band. The smallest contractile unit in the fiber is called the sarcomere which is a repeating unit within two Z bands. The sarcoplasm also contains glycogen which provides energy to the cell during heightened exercise, and myoglobin, the red pigment that stores oxygen until needed for muscular activity.[14]

The sarcoplasmic reticulum, a specialized type of smooth endoplasmic reticulum, forms a network around each myofibril of the muscle fiber. This network is composed of groupings of two dilated end-sacs called terminal cisternae, and a single T-tubule (transverse tubule), which bores through the cell and emerge on the other side; together these three components form the triads that exist within the network of the sarcoplasmic reticulum, in which each T-tubule has two terminal cisternae on each side of it. The sarcoplasmic reticulum serves as a reservoir for calcium ions, so when an action potential spreads over the T-tubule, it signals the sarcoplasmic reticulum to release calcium ions from the gated membrane channels to stimulate muscle contraction.[14][15]

In skeletal muscle, at the end of each muscle fiber, the outer layer of the sarcolemma combines with tendon fibers at the

Cardiac muscle cells

The cell membrane of a

Cardiac muscle like the skeletal muscle is also striated and the cells contain myofibrils, myofilaments, and sarcomeres as the skeletal muscle cell. The cell membrane is anchored to the cell's cytoskeleton by anchor fibers that are approximately 10 nm wide. These are generally located at the Z lines so that they form grooves and transverse tubules emanate. In cardiac myocytes, this forms a scalloped surface.[18]

The cytoskeleton is what the rest of the cell builds off of and has two primary purposes; the first is to stabilize the topography of the intracellular components and the second is to help control the size and shape of the cell. While the first function is important for biochemical processes, the latter is crucial in defining the surface-to-volume ratio of the cell. This heavily influences the potential electrical properties of

Smooth muscle cells

Smooth muscle cells are spindle-shaped with wide middles, and tapering ends. They have a single nucleus and range from 30 to 200 micrometers in length. This is thousands of times shorter than skeletal muscle fibers. The diameter of their cells is also much smaller which removes the need for T-tubules found in striated muscle cells. Although smooth muscle cells lack sarcomeres and myofibrils they do contain large amounts of the contractile proteins actin and myosin. Actin filaments are anchored by dense bodies (similar to the Z discs in sarcomeres) to the sarcolemma.[19]

Development

A

Myoblasts in skeletal muscle that do not form muscle fibers dedifferentiate back into myosatellite cells. These satellite cells remain adjacent to a skeletal muscle fiber, situated between the sarcolemma and the basement membrane[23] of the endomysium (the connective tissue investment that divides the muscle fascicles into individual fibers). To re-activate myogenesis, the satellite cells must be stimulated to differentiate into new fibers.

Myoblasts and their derivatives, including satellite cells, can now be generated in vitro through

Function

Muscle contraction in striated muscle

Skeletal muscle contraction

When

Excitation of a myocyte causes depolarization at its synapses, the

When the acetylcholine is released it diffuses across the synapse and binds to a receptor on the sarcolemma, a term unique to muscle cells that refers to the cell membrane. This initiates an impulse that travels across the sarcolemma.[28]

When the action potential reaches the sarcoplasmic reticulum it triggers the release of Ca2+ from the Ca2+ channels. The Ca2+ flows from the sarcoplasmic reticulum into the sarcomere with both of its filaments. This causes the filaments to start sliding and the sarcomeres to become shorter. This requires a large amount of ATP, as it is used in both the attachment and release of every myosin head. Very quickly Ca2+ is actively transported back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, which blocks the interaction between the thin and thick filament. This in turn causes the muscle cell to relax.[28]

There are four main types of muscle contraction: twitch, treppe, tetanus, and isometric/isotonic. Twitch contraction is the process in which a single stimulus signals a single contraction. In twitch contraction, the length of the contraction may vary depending on the size of the muscle cell. During treppe (or summation) contraction muscles do not start at maximum efficiency; instead, they achieve increased strength of contraction due to repeated stimuli. Tetanus involves a sustained contraction of muscles due to a series of rapid stimuli, which can continue until the muscles fatigue. Isometric contractions are skeletal muscle contractions that do not cause movement of the muscle. However, isotonic contractions are skeletal muscle contractions that do cause movement.[28]

Cardiac muscle contraction

Specialized

Evolution

The

Schmid & Seipel (2005)

The origin of true muscle cells is argued by other authors to be the endoderm portion of the mesoderm and the endoderm. However, Schmid & Seipel (2005)[29] counter skepticism – about whether the muscle cells found in ctenophores and cnidarians are "true" muscle cells – by considering that cnidarians develop through a medusa stage and polyp stage. They note that in the hydrozoans' medusa stage, there is a layer of cells that separate from the distal side of the ectoderm, which forms the striated muscle cells in a way similar to that of the mesoderm; they call this third separated layer of cells the ectocodon. Schmid & Seipel argue that even in bilaterians, not all muscle cells are derived from the mesendoderm: Their key examples are that in both the eye muscles of vertebrates, and the muscles of spiralians, these cells derive from the ectodermal mesoderm, rather than the endodermal mesoderm. Furthermore, they argue that since myogenesis does occur in cnidarians with the help of the same molecular regulatory elements found in the specification of muscle cells in bilaterians, that there is evidence for a single origin for striated muscle.[29]

In contrast to this argument for a single origin of muscle cells, Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. (2012)[30] argue that molecular markers such as the myosin II protein used to determine this single origin of striated muscle predate the formation of muscle cells. They use an example of the contractile elements present in the Porifera, or sponges, that do truly lack this striated muscle containing this protein. Furthermore, Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. present evidence for a polyphyletic origin of striated muscle cell development through their analysis of morphological and molecular markers that are present in bilaterians and absent in cnidarians, ctenophores, and bilaterians. Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. showed that the traditional morphological and regulatory markers such as actin, the ability to couple myosin side chains phosphorylation to higher concentrations of the positive concentrations of calcium, and other MyHC elements are present in all metazoans not just the organisms that have been shown to have muscle cells. Thus, the usage of any of these structural or regulatory elements in determining whether or not the muscle cells of the cnidarians and ctenophores are similar enough to the muscle cells of the bilaterians to confirm a single lineage is questionable according to Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. Furthermore, they explain that the orthologues of the Myc genes that have been used to hypothesize the origin of striated muscle occurred through a gene duplication event that predates the first true muscle cells (meaning striated muscle), and they show that the Myc genes are present in the sponges that have contractile elements but no true muscle cells. Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. also showed that the localization of this duplicated set of genes that serve both the function of facilitating the formation of striated muscle genes, and cell regulation and movement genes, were already separated into striated much and non-muscle MHC. This separation of the duplicated set of genes is shown through the localization of the striated much to the contractile vacuole in sponges, while the non-muscle much was more diffusely expressed during developmental cell shape and change. Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. found a similar pattern of localization in cnidarians except with the cnidarian N. vectensis having this striated muscle marker present in the smooth muscle of the digestive tract. Thus, they argue that the pleisiomorphic trait of the separated orthologues of much cannot be used to determine the monophylogeny of muscle, and additionally argue that the presence of a striated muscle marker in the smooth muscle of this cnidarian shows a fundamental different mechanism of muscle cell development and structure in cnidarians.[30]

Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. (2012)[30] further argue for multiple origins of striated muscle in the metazoans by explaining that a key set of genes used to form the troponin complex for muscle regulation and formation in bilaterians is missing from the cnidarians and ctenophores, and 47 structural and regulatory proteins observed, Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. were not able to find even on unique striated muscle cell protein that was expressed in both cnidarians and bilaterians. Furthermore, the Z-disc seemed to have evolved differently even within bilaterians and there is a great deal of diversity of proteins developed even between this clade, showing a large degree of radiation for muscle cells. Through this divergence of the Z-disc, Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. argue that there are only four common protein components that were present in all bilaterians muscle ancestors and that of these for necessary Z-disc components only an actin protein that they have already argued is an uninformative marker through its pleisiomorphic state is present in cnidarians. Through further molecular marker testing, Steinmetz et al. observe that non-bilaterians lack many regulatory and structural components necessary for bilaterians muscle formation and do not find any unique set of proteins to both bilaterians and cnidarians and ctenophores that are not present in earlier, more primitive animals such as the sponges and amoebozoans. Through this analysis, the authors conclude that due to the lack of elements that bilaterian muscles are dependent on for structure and usage, nonbilaterian muscles must be of a different origin with a different set of regulatory and structural proteins.[30]

In another take on the argument, Andrikou & Arnone (2015)[31] use the newly available data on gene regulatory networks to look at how the hierarchy of genes and morphogens and another mechanism of tissue specification diverge and are similar among early deuterostomes and protostomes. By understanding not only what genes are present in all bilaterians but also the time and place of deployment of these genes, Andrikou & Arnone discuss a deeper understanding of the evolution of myogenesis.[31]

In their paper, Andrikou & Arnone (2015)

Evolutionarily, specialized forms of skeletal and

Invertebrate muscle cell types

The properties used for distinguishing fast, intermediate, and slow muscle fibers can be different for invertebrate flight and jump muscle.[33] To further complicate this classification scheme, the mitochondrial content, and other morphological properties within a muscle fiber, can change in a tsetse fly with exercise and age.[34]

See also

- List of human cell types derived from the germ layers

- List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

References

- ^ a b Myocytes at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- PMC 5167519.

- ISBN 9780071222075.

- PMID 11694174. Archived from the originalon 13 February 2015.

- ^ "Does anyone know why skeletal muscle fibers have peripheral nuclei, but the cardiomyocytes not? What are the functional advantages?". Archived from the original on 19 September 2017.

- ^ Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H.; Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark; Desaix, Peter (6 March 2013). "Cardiac muscle tissue". Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ "Muscle tissues". Archived from the original on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ "Atrial structure, fibers, and conduction" (PDF). Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ISBN 9780071222075.

- ^ "Structure of Skeletal Muscle | SEER Training". training.seer.cancer.gov.

- S2CID 20508198.

- PMID 29898810.

- S2CID 234362466.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-337825-1.

- PMID 23691080.

- PMID 23738275.

- PMID 22300977.

- ^ a b c Ferrari, Roberto. "Healthy versus sick myocytes: metabolism, structure and function" (PDF). oxfordjournals.org/en. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ a b Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H.; Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark; Desaix, Peter (6 March 2013). "Smooth muscle". Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ page 395, Biology, Fifth Edition, Campbell, 1999

- PMID 10966875.

- PMID 18400219.

- PMID 16899758.

- S2CID 21241434.

- PMID 18611274.

- ^ "Structure, and Function of Skeletal Muscles". courses.washington.edu. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "Muscle Fiber Excitation". courses.washington.edu. University of Washington. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ a b c Ziser, Stephen. "Muscle Cell Anatomy & Function" (PDF). www.austincc.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ PMID 15936326.

- ^ PMID 22763458.

- ^ .

- PMID 10368962.

- ISBN 9780471877097.

- S2CID 85719905.

External links

Media related to Myocytes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Myocytes at Wikimedia Commons- Structure of a Muscle Cell