Myc

Chr. 8 q24.21 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wikidata | Q20969939 | ||||||

| |||||||

Chr. 1 p34.2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wikidata | Q18029714 | ||||||

| |||||||

Chr. 2 p24.3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wikidata | Q14906753 | ||||||

| |||||||

Myc is a family of

In

Myc is thus viewed as a promising target for anti-cancer drugs.

c-Myc also plays an important role in

In the

In addition to its role as a classical transcription factor, N-myc may recruit histone acetyltransferases (HATs). This allows it to regulate global chromatin structure via histone acetylation.[8]

Discovery

The Myc family was first established after discovery of homology between an oncogene carried by the Avian virus, Myelocytomatosis (v-myc; P10395) and a human gene over-expressed in various cancers, cellular Myc (c-Myc).[citation needed] Later, discovery of further homologous genes in humans led to the addition of n-Myc and l-Myc to the family of genes.[9]

The most frequently discussed example of c-Myc as a proto-oncogene is its implication in

Structure

The protein product of Myc family genes all belong to the Myc family of transcription factors, which contain

Myc

Function

Myc proteins are

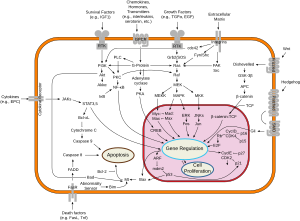

Myc is activated upon various

By modifying the expression of its target genes, Myc activation results in numerous biological effects. The first to be discovered was its capability to drive cell proliferation (upregulates cyclins, downregulates p21), but it also plays a very important role in regulating cell growth (upregulates ribosomal RNA and proteins), apoptosis (downregulates Bcl-2), differentiation, and stem cell self-renewal. Nucleotide metabolism genes are upregulated by Myc,[14] which are necessary for Myc induced proliferation[15] or cell growth.[16]There have been several studies that have clearly indicated Myc's role in cell competition.[17]

A major effect of c-myc is B cell proliferation, and gain of MYC has been associated with B cell malignancies and their increased aggressiveness, including histological transformation.[18] In B cells, Myc acts as a classical oncogene by regulating a number of pro-proliferative and anti-apoptotic pathways, this also includes tuning of BCR signaling and CD40 signaling in regulation of microRNAs (miR-29, miR-150, miR-17-92).[19]

c-Myc induces MTDH(AEG-1) gene expression and in turn itself requires AEG-1 oncogene for its expression.

Myc-nick

Myc-nick is a cytoplasmic form of Myc produced by a partial proteolytic cleavage of full-length c-Myc and N-Myc.[20] Myc cleavage is mediated by the calpain family of calcium-dependent cytosolic proteases.

The cleavage of Myc by calpains is a constitutive process but is enhanced under conditions that require rapid downregulation of Myc levels, such as during terminal differentiation. Upon cleavage, the

The functions of Myc-nick are currently under investigation, but this new Myc family member was found to regulate cell morphology, at least in part, by interacting with

Clinical significance

A large body of evidence shows that Myc genes and proteins are highly relevant for treating tumors.[9] Except for early response genes, Myc universally upregulates gene expression. Furthermore, the upregulation is nonlinear. Genes for which expression is already significantly upregulated in the absence of Myc are strongly boosted in the presence of Myc, whereas genes for which expression is low in the absence Myc get only a small boost when Myc is present.[6]

Inactivation of SUMO-activating enzyme (

Amplification of the MYC gene was found in a significant number of epithelial ovarian cancer cases.[22] In TCGA datasets, the amplification of Myc occurs in several cancer types, including breast, colorectal, pancreatic, gastric, and uterine cancers.[23]

In the experimental transformation process of normal cells into cancer cells, the MYC gene can cooperate with the RAS gene.[24][25]

Expression of Myc is highly dependent on

MYC expression is controlled by a wide variety of noncoding RNAs, including

Animal models

In Drosophila Myc is encoded by the diminutive locus, (which was known to geneticists prior to 1935).[30] Classical diminutive alleles resulted in a viable animal with small body size. Drosophila has subsequently been used to implicate Myc in cell competition,[31] endoreplication,[32] and cell growth.[33]

During the discovery of Myc gene, it was realized that chromosomes that reciprocally translocate to chromosome 8 contained

Relationship to stem cells

Myc genes play a number of normal roles in stem cells including pluripotent stem cells. In neural stem cells, N-Myc promotes a rapidly proliferative stem cell and precursor-like state in the developing brain, while inhibiting differentiation.[36] In hematopoietic stem cells, Myc controls the balance between self-renewal and differentiation.[37] In particular, long-term hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs) express low levels of c-Myc, ensuring self-renewal. Enforced expression of c-Myc in LT-HSCs promotes differentiation at the expense of self-renewal, resulting in stem cell exhaustion.[38] In pathological states and specifically in acute myeloid leukemia, oxidant stress can trigger higher levels of Myc expression that affects the behavior of leukemia stem cells.[39]

c-Myc plays a major role in the generation of

Interactions

Myc has been shown to

- ACTL6A[41]

- BRCA1[42][43][44][45]

- Bcl-2[46]

- Cyclin T1[47]

- CHD8[48]

- DNMT3A[49]

- EP400[50]

- GTF2I[51]

- HTATIP[52]

- let-7[53][54][55]

- MAPK1[46][56][57]

- MAPK8[58]

- MAX[59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71]

- MLH1[63]

- MYCBP2[72]

- MYCBP[73]

- NMI[42]

- NFYB[74]

- NFYC[75]

- P73[76]

- PCAF[77]

- PFDN5[78][79]

- RuvB-like 1[41][50]

- SAP130[77]

- SMAD2[80]

- SMAD3[80]

- SMARCA4[41][59]

- SMARCB1[62]

- SUPT3H[77]

- TIAM1[81]

- TADA2L[77]

- TAF9[77]

- TFAP2A[82]

- TRRAP[41][60][61][77]

- WDR5[83]

- YY1[84] and

- ZBTB17.[85][86]

- C2orf16[87]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Myc". NCBI.

- PMID 2834731.

- ^ Begley S (2013-01-09). "DNA pioneer James Watson takes aim at cancer establishments". Reuters.

- PMID 30597997.

- PMID 28643779.

- ^ PMID 23021216.

- PMID 17928593.

- PMID 19047142.

- ^ .

- PMID 24384817.

- S2CID 4422771.

- PMID 1886715.

- S2CID 29661004.

- PMID 18628958.

- PMID 18677108.

- PMID 26889675.

- S2CID 4414411.

- PMID 11163229.

- PMID 18423194.

- PMID 20691906.

- PMID 22157079.

- PMID 23791828.

- PMID 24874471.

- S2CID 2338865.

- S2CID 2972931.

- PMID 24466310.

- PMID 24905006.

- PMID 21889194.

- PMID 34440124.

- PMID 17246888.

- S2CID 18357397.

- S2CID 721144.

- S2CID 5215149. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2022-04-03. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

- PMID 27281222.

- ^ "Scientists identify drugs to target 'Achilles heel' of Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia cells". myScience. 2016-06-08. Archived from the original on 2018-07-27. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- PMID 12381668.

- PMID 15545632.

- PMID 15545632.

- PMID 38201575.

- S2CID 7593915.

- ^ PMID 11839798.

- ^ PMID 11916966.

- PMID 14612409.

- PMID 12646176.

- S2CID 30771256.

- ^ PMID 15210690.

- S2CID 29519364.

- PMID 25452129.

- PMID 15616584.

- ^ S2CID 15634637.

- S2CID 4354157.

- PMID 12776177.

- PMID 18066065.

- PMID 17877811.

- PMID 15769738.

- S2CID 45404088.

- PMID 9207092.

- PMID 10551811.

- ^ PMID 17353931.

- ^ PMID 10611234.

- ^ S2CID 17693834.

- ^ S2CID 12945791.

- ^ PMID 12584560.

- PMID 2006410.

- PMID 12391307.

- PMID 10593926.

- S2CID 30576019.

- PMID 9184233.

- S2CID 16142388.

- PMID 10229200.

- S2CID 17891130.

- PMID 9689053.

- S2CID 41886122.

- PMID 11282029.

- PMID 10446203.

- PMID 12080043.

- ^ PMID 12660246.

- PMID 9792694.

- PMID 11567024.

- ^ PMID 11804592.

- PMID 12446731.

- PMID 7729426.

- PMID 25818646.

- PMID 8266081.

- S2CID 12696178.

- PMID 9312026.

- ^ "PSICQUIC View". ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 2019-05-02.

Further reading

- Ruf IK, Rhyne PW, Yang H, Borza CM, Hutt-Fletcher LM, Cleveland JL, Sample JT (2001). "EBV Regulates c-MYC, Apoptosis, and Tumorigenicity in Burkitt's Lymphoma". Epstein-Barr Virus and Human Cancer. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 258. pp. 153–60. PMID 11443860.

- Lüscher B (October 2001). "Function and regulation of the transcription factors of the Myc/Max/Mad network". Gene. 277 (1–2): 1–14. PMID 11602341.

- Hoffman B, Amanullah A, Shafarenko M, Liebermann DA (May 2002). "The proto-oncogene c-myc in hematopoietic development and leukemogenesis". Oncogene. 21 (21): 3414–21. S2CID 8720539.

- Pelengaris S, Khan M, Evan G (October 2002). "c-MYC: more than just a matter of life and death". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2 (10): 764–76. S2CID 13226062.

- Nilsson JA, Cleveland JL (December 2003). "Myc pathways provoking cell suicide and cancer". Oncogene. 22 (56): 9007–21. S2CID 24758874.

- Dang CV, O'donnell KA, Juopperi T (September 2005). "The great MYC escape in tumorigenesis". Cancer Cell. 8 (3): 177–8. PMID 16169462.

- Dang CV, Li F, Lee LA (November 2005). "Could MYC induction of mitochondrial biogenesis be linked to ROS production and genomic instability?". Cell Cycle. 4 (11): 1465–6. PMID 16205115.

- Coller HA, Forman JJ, Legesse-Miller A (August 2007). ""Myc'ed messages": myc induces transcription of E2F1 while inhibiting its translation via a microRNA polycistron". PLOS Genetics. 3 (8): e146. PMID 17784791.

- Astrin SM, Laurence J (May 1992). "Human immunodeficiency virus activates c-myc and Epstein-Barr virus in human B lymphocytes". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 651 (1): 422–32. S2CID 31980333.

- Bernstein PL, Herrick DJ, Prokipcak RD, Ross J (April 1992). "Control of c-myc mRNA half-life in vitro by a protein capable of binding to a coding region stability determinant". Genes & Development. 6 (4): 642–54. PMID 1559612.

- Iijima S, Teraoka H, Date T, Tsukada K (June 1992). "DNA-activated protein kinase in Raji Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Phosphorylation of c-Myc oncoprotein". European Journal of Biochemistry. 206 (2): 595–603. PMID 1597196.

- Seth A, Alvarez E, Gupta S, Davis RJ (December 1991). "A phosphorylation site located in the NH2-terminal domain of c-Myc increases transactivation of gene expression". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 266 (35): 23521–4. PMID 1748630.

- Takahashi E, Hori T, O'Connell P, Leppert M, White R (1991). "Mapping of the MYC gene to band 8q24.12----q24.13 by R-banding and distal to fra(8)(q24.11), FRA8E, by fluorescence in situ hybridization". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 57 (2–3): 109–11. PMID 1914517.

- Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN (March 1991). "Max: a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that forms a sequence-specific DNA-binding complex with Myc". Science. 251 (4998): 1211–7. PMID 2006410.

- Gazin C, Rigolet M, Briand JP, Van Regenmortel MH, Galibert F (September 1986). "Immunochemical detection of proteins related to the human c-myc exon 1". The EMBO Journal. 5 (9): 2241–50. PMID 2430795.

- Lüscher B, Kuenzel EA, Krebs EG, Eisenman RN (April 1989). "Myc oncoproteins are phosphorylated by casein kinase II". The EMBO Journal. 8 (4): 1111–9. PMID 2663470.

- Finver SN, Nishikura K, Finger LR, Haluska FG, Finan J, Nowell PC, Croce CM (May 1988). "Sequence analysis of the MYC oncogene involved in the t(8;14)(q24;q11) chromosome translocation in a human leukemia T-cell line indicates that putative regulatory regions are not altered". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 85 (9): 3052–6. PMID 2834731.

- Showe LC, Moore RC, Erikson J, Croce CM (May 1987). "MYC oncogene involved in a t(8;22) chromosome translocation is not altered in its putative regulatory regions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 84 (9): 2824–8. PMID 3033665.

- Guilhot S, Petridou B, Syed-Hussain S, Galibert F (December 1988). "Nucleotide sequence 3' to the human c-myc oncogene; presence of a long inverted repeat". Gene. 72 (1–2): 105–8. PMID 3243428.

- Hann SR, King MW, Bentley DL, Anderson CW, Eisenman RN (January 1988). "A non-AUG translational initiation in c-myc exon 1 generates an N-terminally distinct protein whose synthesis is disrupted in Burkitt's lymphomas". Cell. 52 (2): 185–95. S2CID 3012009.

External links

- InterPro signatures for protein family: IPR002418, IPR011598, IPR003327

- The Myc Protein

- NCBI Human Myc protein

- Myc cancer gene

- myc+Proto-Oncogene+Proteins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Generating iPS Cells from MEFS through Forced Expression of Sox-2, Oct-4, c-Myc, and Klf4

- Drosophila Myc - The Interactive Fly

- FactorBook C-Myc

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the structure information available in the PDB for Human Myc proto-oncogene protein