Naegleria fowleri

This article is missing information about genome assemblies (drafts and one unpublished but finished genome on NCBI). (January 2021) |

| Naegleria fowleri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Diagram depicting the stages of Naegleria fowleri’s life-cycle and environment at that stage | |

| |

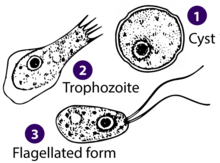

| Drawings of the three stages Naegleria fowleri’s life-cycle | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Phylum: | Percolozoa |

| Class: | Heterolobosea

|

| Order: | Schizopyrenida |

| Family: | Vahlkampfiidae |

| Genus: | Naegleria |

| Species: | N. fowleri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Naegleria fowleri Carter (1970)

| |

Naegleria fowleri, also known as the brain-eating amoeba, is a species of the genus Naegleria. It belongs to the phylum Percolozoa and is technically classified as an amoeboflagellate excavate,[1] rather than a true amoeba. This free-living microorganism primarily feeds on bacteria but can become pathogenic in humans, causing an extremely rare, sudden, severe, and usually fatal brain infection known as naegleriasis or primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM).[2]

It is typically found in warm freshwater bodies such as lakes,[3] rivers, hot springs,[4] warm water discharge from industrial or power plants,[5] geothermal well water,[6] lakes and poorly maintained or minimally chlorinated swimming pools with residual chlorine levels under 0.5 mg/m3,[7][8] water heaters,[9] soil, and pipes connected to tap water.[10] It can exist in either an amoeboid or temporary flagellate stage.[11]

Etymology

The organism was named after Malcolm Fowler, an Australian pathologist at Adelaide Children's Hospital, who was the first author of the original series of case reports of PAM.[12][13]

Life cycle

Naegleria fowleri, a

Cyst stage

To endure harsh environmental conditions, trophozoites transform into microbial cysts,[16] spherical, single-layered structures about 7–15 µm in diameter, enclosing a single cell nucleus.[17] Acting as a resilient capsule, the cyst enables the amoeba to withstand adverse circumstances. Factors triggering cyst formation include food scarcity, overcrowding, desiccation, waste accumulation, and cold temperatures. When conditions improve, the amoeba can emerge through the pore or ostiole at the center of the cyst. N. fowleri has been observed to encyst at temperatures below 10 °C (50 °F).[17][16]

Trophozoite stage

The

Trophozoites are characterized by a nucleus surrounded by a flexible membrane. They move via

As trophozoites, Naegleria fowleri may develop approximately 1 to 12 structures on their membrane known as amoebastomes (amorphous cytostomes), also referred to as "suckers" or "food cups," which they use for feeding in a manner similar to trogocytosis.[18]

Flagellate stage

The flagellate stage of Naegleria fowleri is pear-shaped and biflagellate (with two flagella). This stage can be inhaled into the nasal cavity, typically during activities such as swimming or diving. The flagellate form develops when trophozoites are exposed to a change in ionic strength in the fluid it is in, such as being placed in distilled water. The flagellate form does not exist in human tissue, but can be present in the cerebrospinal fluid. Once inside the nasal cavity, the flagellated form transforms into a trophozoite within a few hours.[17]

Ecology

Naegleria fowleri, an excavata, inhabits soil and water. It is sensitive to drying and acidic conditions, and cannot survive in seawater. The amoeba thrives at moderately elevated temperatures, making infections more likely during summer months. N. fowleri is a facultative thermophile, capable of growing at temperatures up to 46 °C (115 °F).[11] Warm freshwater with an ample supply of bacteria as food provides a suitable habitat for amoebae. Locations where many amoebic infections have occurred include artificial bodies of water, disturbed natural habitats, areas with soil, and unchlorinated or unfiltered water.

N. fowleri appears to flourish during periods of disturbance. The "flagellate-empty" hypothesis suggests that Naegleria's success may stem from decreased

Pathogenicity

N. fowleri may cause a usually fatal infection of the brain called

N. fowleri normally eat bacteria, but during human infections, the trophozoites consume

The disease presents diagnostic challenges to medical professionals as early symptoms can be mild. 16% of cases presented with early flu-like symptoms only. [22] Symptoms may also appear similar to a viral or bacterial meningitis which may delay correct diagnosis and treatment.[24] Most cases have been diagnosed post-mortem following a biopsy of patient brain tissue. [25] It takes one to twelve days, median five, for symptoms to appear after nasal exposure to N. fowleri flagellates.[26] Symptoms may include headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, altered mental state, coma, drooping eyelid, blurred vision, and loss of the sense of taste.[27] Later symptoms may include stiff neck, confusion, lack of attention, loss of balance, seizures, and hallucinations. Once symptoms begin to appear, the patient usually dies within two weeks. N. fowleri is not contagious; an infected person cannot transmit the infection.

Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis is classified as a rare disease in the United States as it affects fewer than 200,000 people.[28] From 2013 to 2022, 29 infections were reported in the US, which compares with about 4,000 annual deaths by drowning.[29] It is so rare that individual cases are often reported internationally, with 381 cases reported globally.[22][30] The true number of cases is likely to be higher than those reported due to problems relating to diagnosis, access to diagnostic testing and a lack of surveillance. [22]

Animals may be infected by Naegleria fowleri. This is rarely observed, although it may occur and be overlooked. Experimentally, mice, guinea pigs, and sheep have been infected, and there have been reports of South American tapirs and cattle contracting PAM.[31]

Treatment

The core antimicrobial treatment consists of the antifungal drug amphotericin B,[32] which inhibits the pathogen by binding to its cell membrane sterols, causing cell membrane disruption and pathogen death;[33] however, even with this treatment, the fatality rate is greater than 97%.[29][34] New treatments are being sought.[29][35] Miltefosine, an antiparasitic drug that inhibits the pathogen via disrupting its cell survival signal pathway PI3K/Akt/mTOR,[33] has been used in a few cases with mixed results.[36] Other treatments include Dexamethasone and therapeutic hypothermia,[37] that may be utilised to reduce inflammation. Therapeutic hypothermia reduces the body's temperature to a hypothermic state [38] to prevent further brain injury resulting from hyper inflammation and increased intracranial pressure. [39]

A key factor to effective treatment is the speed of diagnosis. Naegleriasis is rare, and is often not considered as a likely diagnosis; therefore, the clinical laboratory's identification of the microorganism may be the first time an amoebic etiology is considered. Rapid identification can help to avoid delays in diagnosis and therapy. Amoeba cultures and

Preventing human infection

A large proportion of reported cases of infection had a history of water exposure, 58% from swimming or diving, 16% from bathing, 10% from water sports such as jet skiing, water-skiing and wakeboarding and 9% from nasal irrigation. [22] Methods of infection prevention therefore focus on precautions to be taken around water to prevent water entering the nose, particularly during warmer weather. Wearing a nose clip when swimming may help to prevent contaminated water travelling up the nasal cavity. Keeping the head above water and not jumping or diving into warm fresh water may also prevent contaminated water from going up the nose. Swimmers should also avoid digging or stirring up sediment at the bottom of lakes, ponds and rivers as this is where amebae are most likely to live. [41][42]

When irrigating sinuses or taking part in ritual cleansing of the nasal cavity, it is advised to use boiled or distilled water. [43]

Cases in Pakistan

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

Cases of infection in Pakistan account for 11% of reported cases globally.[22] In Pakistan, the number of reported cases has surpassed the global total due to insufficient healthcare infrastructure and limited awareness of Naegleria fowleri. As a result, only a small fraction of cases are correctly identified as primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), with the majority of cases misdiagnosed as viral meningitis.

For the very first time in Pakistan, N. fowleri genotype has been identified as type-2. Phylogenetic analysis showed that N. fowleri isolate from Pakistan is among the latest descendants, i.e., evolved later in life.[44]

See also

- Acanthamoeba – an amoeba that can cause amoebic keratitis and encephalitis in humans

- Balamuthia mandrillaris – an amoeba that is the cause of (often fatal) granulomatous amoebic meningoencephalitis

- Entamoeba histolytica – an amoeba that is the cause of amoebiasis, or amoebic dysentery

- Leptospira – a zoonotic bacteria that causes leptospirosis

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

- Necrotizing fasciitis – the "flesh-eating disease", caused by certain types of bacteria

- Toxoplasma gondii – cat-carried protozoan that causes the disease toxoplasmosis

- Vibrio vulnificus – warm saltwater infectious bacteria

References

- PMID 15313128.

- ^ "Texas residents warned of tap water tainted with brain-eating microbe". The Guardian. Associated Press. 26 September 2020. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- PMID 596870.

- PMID 14532044.

- PMID 6847189.

- PMID 14532037.

- S2CID 7828942.

- S2CID 5972631.

- PMID 22919000.

- ^ a b "Naegleria fowleri — Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM): Ritual Nasal Rinsing & Ablution". www.cdc.gov. CDC. 2023-05-03. Archived from the original on 2022-11-30.

- ^ a b "Naegleria fowleri — Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM): General Information". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2023-05-03. Archived from the original on 2018-07-28.

- PMID 5825411.

- ^ "The discovery of amoebic meningitis in Northern Spencer Gulf towns". samhs.org. South Australian Medical Heritage Society Inc. Archived from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- PMID 20048302.

- ^ "Brain-eating-amoeba". WebMD. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ PMID 637538.

- ^ PMID 3280964.

- PMID 6696410.

- PMID 25930186.

- ^ "Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM) - Naegleria fowleri | Parasites | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-06-24. Archived from the original on 2019-01-29. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- ^ "Naegleria and Amebic Meningoencephalitis – Minnesota Dept. of Health". www.health.state.mn.us. Archived from the original on 2022-12-28. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- ^ PMID 32369575.

- PMID 27447543.

- ^ "Illness and Symptoms | Naegleria fowleri | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-05-03. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- PMID 34572533.

- ^ "Naegleria fowleri – Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM): Illness & Symptoms". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). May 3, 2023. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020.

- ^ "Brain-Eating Amoeba (Naegleria Fowleri): FAQ, Symptoms, Treatment". WebMD. 2021-09-29. Archived from the original on 2022-12-28.

- ^ "General Information | Naegleria fowleri | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-05-03. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- ^ a b c d e "Frequently asked questions about Naegleria fowleri, commonly known as the "brain-eating ameba"". CDC.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). May 3, 2023. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020.

- ^ Helmore, Edward (19 September 2023). "Arkansas child dies of rare brain-eating amoeba after playing at country club". The Guardian (UK).

- ^ "Naegleria Fowleri in Animals" (PDF). ldh.la.gov. Infectious Disease Epidemiology Section, Office of Public Health, Louisiana Dept of Health & Hospitals. 25 September 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2023.

- ^ Subhash Chandra Parija (Nov 23, 2015). "Naegleria Infection Treatment & Management". Medscape. Archived from the original on November 13, 2019.

- ^ PMID 26259797.

- S2CID 8912435.

- ^ Wessel, Lindzi (22 July 2016). "Scientists scour the globe for a drug to kill deadly brain-eating amoeba". STAT. Archived from the original on 6 October 2020.

- ^ Wessel, Linda (16 September 2016). "A life-saving drug that treats a rare infection is almost impossible to find". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016.

- ^ "Treatment | Naegleria fowleri | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-05-03. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- ^ "Treatment | Naegleria fowleri | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-05-03. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- PMID 34572533.

- PMID 27525348.

- ^ CDC (2022-08-19). "Naegleria fowleri infections are rare". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- ^ "Pathogen and Environment | Naegleria fowleri | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2022-10-18. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- ^ "Ritual Nasal Rinsing & Ablution | Naegleria fowleri | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-05-03. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- PMID 36046566.

External links

- Naegleria information site from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Naegleria from The Tree of Life Web Project