Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic Naxçıvan Muxtar Respublikası (Azerbaijani) | ||

|---|---|---|

Autonomous republic of Azerbaijan | ||

|

Nakhchivan ASSR February 9, 1924 | | |

| Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic | November 17, 1990 | |

| Capital and largest city | Nakhchivan | |

| Official languages | Azerbaijani | |

| Demonym(s) | Nakhchivani | |

| Government | Autonomous parliamentary republic | |

• President's plenipotentiary representative | Fuad Najafli | |

• Acting chairman of the Supreme Assembly | Azer Zeynalov | |

| Sabuhi Mammadov | ||

| Legislature | UTC+4 (AZT) | |

| Calling code | +994 36 | |

| ISO 3166 code | AZ | |

The Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (Azerbaijani: Naxçıvan Muxtar Respublikası, pronounced [nɑxtʃɯˈvɑn muxˈtɑɾ ɾesˈpublikɑsɯ])[2] is a landlocked exclave of the Republic of Azerbaijan. The region covers 5,502.75 km2 (2,124.62 sq mi)[3] with a population of 459,600.[4] It is bordered by Armenia[a] to the east and north, Iran[b] to the southwest, and Turkey[c] to the west. It is the sole autonomous republic of Azerbaijan, governed by its own elected legislature.

The republic, especially the capital city of Nakhchivan, has a long history dating back to about 1500 BC. Nakhijevan was one the cantons of the historical Armenian province of Vaspurakan in the Kingdom of Armenia. Historically, the Persians, Armenians, Mongols, and Turks all competed for the region.[2] The area that is now Nakhchivan became part of Safavid Iran in the 16th century. The semi-autonomous Nakhchivan Khanate was established there in the mid-18th century. In 1828, after the last Russo-Persian War and the Treaty of Turkmenchay, the Nakhchivan Khanate passed from Iranian into Imperial Russian possession.

After the 1917 February Revolution, Nakhchivan and its surrounding region were under the authority of the Special Transcaucasian Committee of the Russian Provisional Government and subsequently of the short-lived Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. When the TDFR was dissolved in May 1918, Nakhchivan, Nagorno-Karabakh, Syunik, and Qazakh were heavily contested between the newly formed and short-lived states of the First Republic of Armenia and the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR). In June 1918, the region came under Ottoman occupation. Under the terms of the Armistice of Mudros, the Ottomans agreed to pull their troops out of the Transcaucasus to make way for British occupation at the close of the First World War. The British placed Nakhchivan under Armenian administration in April 1919, although an Azerbaijani revolt prevented Armenia from establishing full control over the territory.

In July 1920, the

Though a mixed Armenian–Azerbaijani region as late as a century ago,[8][9][10][11] Nakhchivan is homogeneously Azerbaijani today besides a small population of Russians.[2]

Etymology

Variations of the name Nakhchivan include Nakhichevan,[12] Naxcivan,[13] Naxçivan,[14] Nachidsheuan,[citation needed] Nakhijevan,[15] Nuhișvân,[16][self-published source] Nakhchawan,[17] Nakhitchevan,[18] Nakhjavan,[19] and Nakhdjevan.[20] Nakhchivan is mentioned in Ptolemy's Geography and by other classical writers as "Naxuana".[21][22]

The older form of the name is Naxčawan (Armenian: Նախճաւան).[23] According to philologist Heinrich Hübschmann, the name was originally borne by the namesake city (modern Nakhchivan) and later given to the region.[23] Hübschmann believed the name to be composed of Naxič or Naxuč (probably a personal name) and awan, an Armenian word (ultimately of Iranian origin) meaning "place, town".[23]

In the Armenian tradition, the name of the region and its namesake city is connected with the Biblical narrative of Noah's Ark and interpreted as meaning "place of the first descent" or "first resting place" (as if deriving from նախ, nax, 'first' and իջեւան, ijewan, 'abode, resting place') due to it being regarded as the site where Noah descended and settled after the landing of the Ark on nearby Mount Ararat.[24][25] It was probably under the influence of this tradition that the name changed in Armenian from the older Naxčawan to Naxijewan.[25] Although this is a folk etymology, William Whiston believed Nakhchivan/Nakhijevan to be the Apobatērion ("place of descent") mentioned by the first-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus in connection with Noah's Ark, which would make the tradition connecting the name with the Biblical figure Noah very old, predating Armenia's conversion to Christianity in the early fourth century.[25][26][27]

History

Early history

The oldest material culture artifacts found in the region date back to the

The region was part of the states of

In 189 BC, Nakhchivan became part of the new

From 640 on, the Arabs invaded Nakhchivan and undertook many campaigns in the area, crushing all resistance and attacking Armenian nobles who remained in contact with the Byzantines or who refused to pay tribute. In 705, after suppressing an Armenian revolt, Arab viceroy Muhammad ibn Marwan decided to eliminate the Armenian nobility.[40] In Nakhchivan, several hundred Armenian nobles were locked up in churches and burnt, while others were crucified.[18][40]

The violence caused many Armenian princes to flee to the neighboring

About 1055, the

Iranian rule

In the

On the twenty-seventh day they reached the plain of Nakhichevan. Out of fear of the victorious army, the people deserted the cities, villages, houses, and places of dwelling, which were so desolate that they were occupied by owls and crows and struck the onlooker with terror. Moreover, they [the Ottomans] ruined and laid waste all of the villages, towns, fields, and buildings along the road over a distance of four or five days' march so that there was no sign of any buildings or life.[34]

In 1604,

Many of the Armenian deportees were settled in the neighborhood of

Passing to Imperial Russian rule

After the last

The Nakhchivan Khanate was dissolved in 1828 the same year it came into Russian possession, and its territory was merged with the territory of the

War and revolution

In the final year of

Under British occupation, Sir Oliver Wardrop, British Chief Commissioner in the South Caucasus, made a border proposal to solve the conflict. According to Wardrop, Armenian claims against Azerbaijan should not go beyond the administrative borders of the former Erivan Governorate (which under prior Imperial Russian rule encompassed Nakhchivan), while Azerbaijan was to be limited to the governorates of Baku and Elizavetpol. This proposal was rejected by both Armenians (who did not wish to give up their claims to Qazakh, Zangezur and Karabakh) and Azeris (who found it unacceptable to give up their claims to Nakhchivan). As disputes between both countries continued, it soon became apparent that the fragile peace under British occupation would not last.[60]

In December 1918, with the support of Azerbaijan's

You cannot persuade a party of frenzied nationalists that two blacks do not make a white; consequently, no day went by without a catalogue of complaints from both sides, Armenians and Tartars [Azeris], of unprovoked attacks, murders, village burnings and the like. Specifically, the situation was a series of vicious cycles.[61]

By mid-June 1919, however, Armenia succeeded in establishing control over Nakhchivan and the whole territory of the self-proclaimed republic. The fall of the Aras republic triggered an invasion by the regular Azerbaijani army and by the end of July, the Armenian administration was ousted from Nakhchivan.[60] Again, more violence erupted leaving some ten thousand Armenians dead and forty-five Armenian villages destroyed.[17] Meanwhile, feeling the situation to be hopeless and unable to maintain any control over the area, the British decided to withdraw from the region in mid-1919.[62] Still, fighting between Armenians and Azeris continued and after a series of skirmishes that took place throughout the Nakhchivan district, a cease-fire agreement was concluded. However, the cease-fire lasted only briefly, and by early March 1920, more fighting broke out, primarily in Karabakh between Karabakh Armenians and Azerbaijan's regular army. This triggered conflicts in other areas with mixed populations, including Nakhchivan.

Following the adoption of the name of "

Sovietization

In July 1920, the

As of today, the old frontiers between Armenia and Azerbaijan are declared to be non-existent. Mountainous Karabagh, Zangezur and Nakhchivan are recognised to be integral parts of the Socialist Republic of Armenia.[65][66]

The Turkish Government and the Soviet Governments of Armenia and Azerbaijan are agreed that the region of Nakhchivan, within the limits specified by Annex III to the present Treaty, constitutes an autonomous territory under the protection of Azerbaijan.[68]

Thus, on February 9, 1924, the Soviet Union officially established the Nakhchivan ASSR. Its constitution was adopted on April 18, 1926.[32]

In the Soviet Union

As a constituent part of the Soviet Union, tensions lessened over the ethnic composition of Nakhchivan or any territorial claims regarding it. Instead, it became an important point of industrial production with particular emphasis on the mining of minerals such as salt. Under Soviet rule, it was once a major junction on the Moscow-

Facilities improved during Soviet times. Education and public health especially began to see some major changes. In 1913, Nakhchivan only had two hospitals with a total of 20 beds. The region was plagued by widespread diseases including trachoma and typhus. Malaria, which mostly came from the adjoining Aras River, brought serious harm to the region. At any one time, between 70% and 85% of Nakhchivan's population was infected with malaria, and in the region of Norashen (present-day Sharur) almost 100% were struck with the disease. This situation improved dramatically under Soviet rule. Malaria was sharply reduced and trachoma, typhus, and relapsing fever were eliminated.[32]

During the Soviet era, Nakhchivan saw a great demographic shift. In 1926, 15% of the region's population was Armenian, but by 1979, this number had shrunk to 1.4%.

Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh noted similar though slower demographic trends and feared an eventual "de-Armenianization" of the area.

December 1989 saw unrest in Nakhchivan as its Azeri inhabitants moved to physically dismantle the Soviet border with Iran to flee the area and meet their ethnic Azeri cousins in northern Iran. This action was angrily denounced by the Soviet leadership and the Soviet media accused the Azeris of "embracing Islamic fundamentalism".[72]

Declaring independence

On Saturday, January 20, 1990,

In the post-Soviet era

Nakhchivan became a scene of conflict during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. On May 4, 1992, Armenian forces shelled the raion of Sadarak.[80][81][82] The Armenians claimed that the attack was in response to cross-border shelling of Armenian villages by Azeri forces from Nakhchivan.[83][84] David Zadoyan, a 42-year-old Armenian physicist and mayor of the region, said that the Armenians lost patience after months of firing by the Azeris. "If they were sitting on our hilltops and harassing us with gunfire, what do you think our response should be?" he asked.[85] The government of Nakhchivan denied these charges and instead asserted that the Armenian assault was unprovoked and specifically targeted the site of a bridge between Turkey and Nakhchivan.[84] "The Armenians do not react to diplomatic pressure," Nakhchivan foreign minister Rza Ibadov told the ITAR-Tass news agency, "It's vital to speak to them in a language they understand." Speaking to the agency from the Turkish capital Ankara, Ibadov said that Armenia's aim in the region was to seize control of Nakhchivan.[86] According to Human Rights Watch, hostilities broke out after three people were killed when Armenian forces began shelling the region.[87]

The heaviest fighting took place on May 18, when the Armenians captured Nakhchivan's exclave of

The conflict in the area caused a harsh reaction from Turkey. Turkish Prime Minister

Recent times

Today, Nakhchivan retains its autonomy as the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, and is internationally recognized as a constituent part of Azerbaijan governed by

Economic hardships and energy shortages plague the area. There have been many cases of migrant workers seeking jobs in neighboring Turkey. "Emigration rates to Turkey," one analyst said, "are so high that most of the residents of the Besler district in Istanbul are Nakhchivanis."[93] In 2007, an agreement was struck with Iran to obtain more gas exports, and a new bridge on the Aras River between the two countries was inaugurated in October 2007; the Azerbaijani president, Ilham Aliyev and the first vice-president of Iran, Parviz Davoodi also attended the opening ceremony.[95]

As part of the 2020 ceasefire agreement which ended the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, Armenia, in the context of all economic and transport connections in the region to be unblocked, agreed "to guarantee the security of transport connections between the western regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic in order to arrange unobstructed movement of persons, vehicles and cargo in both directions". As part of the agreement, these transport communications are to be patrolled by Border Service of the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation.[96]

Administrative divisions

Nakhchivan is subdivided into eight

| Map ref. | Administrative division | Capital | Type | Area (km2) | Population (August 1, 2011, estimate)[97] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Babek (Babək) | Babek

|

District | 749,81[97] | 66,200[97] | Formerly known as Nakhchivan; renamed after Babak Khorramdin in 1991 |

| 2 | Julfa (Culfa) | Julfa | District | 1012,75[97] | 43,000[97] | Also spelled Jugha or Dzhulfa. |

| 3 | Kangarli (Kəngərli) | Givraq | District | 711,86[97] | 28,900[97] | Split from Babek in March 2004 |

| 4 | Nakhchivan City (Naxçıvan Şəhər)

|

n/a | Municipality | 191,82[97] | 85,700[97] | Split from Nakhchivan (Babek) in 1991 |

| 5 | Ordubad | Ordubad

|

District | 994,88[97] | 46,500[97] | Split from Julfa during Sovietization[17] |

| 6 | Sadarak (Sədərək) | Heydarabad | District | 153,49[97] | 14,500[97] | Split from Sharur in 1990; de jure includes the Karki exclave in Armenia, which is de facto under Armenian control

|

| 7 | Shahbuz (Şahbuz) | Shahbuz | District | 838,04[97] | 23,400[97] | Split from Nakhchivan (Babek) during Sovietization[17] Territory roughly corresponds to the Čahuk (Չահւք) district of the historic Syunik region within the Kingdom of Armenia[98] |

| 8 | Sharur (Şərur) | Sharur

|

District | 847,35[97] | 106,600[97] | Formerly known as Bashnorashen during its incorporation into the Soviet Union and Ilyich (after Vladimir Ilyich Lenin) from the post-Sovietization period to 1990[17] |

| Total | 5,500[97] | 414,900[97] |

Demographics

Ethnic groups in Nakhchivan

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Azerbaijanis[dn 1] | % | Armenians | % | Others[dn 2] | % | Total |

| 1828[99] | 2,024[dn 3] | 55.3 | 1,632 | 44.7 | 3,656 | ||

| 1831[100] | 56.1 | 43.7 | 27 | 1.2 | 30,507 | ||

| 1896[101] | 56.9 | 42.2 | 0.7 | 86,878 | |||

| 18975[102] | 63.7 | 34.4 | 1.9 | 100,771 | |||

| 1916[103][104][e] | 59.3 | 39.6 | 1.1 | 136,859 | |||

| 1926[105] | 84.3 | 10.8 | 4.7 | 104,656 | |||

| 1939[106] | 85.7 | 10.5 | 3.8 | 126,696 | |||

| 1959[106] | 90.2 | 6.7 | 3.1 | 141,361 | |||

| 1970[106] | 93.8 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 202,187 | |||

| 1979[106] | 95.6 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 240,459 | |||

| 1989[106] | 95.9 | 0.6 | 3.5 | 293,875 | |||

| 1999[107] | 99.1 | 0 | 0.9 | 354,072 | |||

| 2009[108] | 99.6 | 0 | 0.4 | 398,323 | |||

| |||||||

As of January 1, 2018, Nakhchivan's population was estimated to be 452,831.[109] Most of the population are Azerbaijanis, who constituted 99% of the population in 1999, while ethnic Russians (0.15%) and a minority of Kurds (0.6%) constituted the remainder of the population.[110]

The Kurds of Nakhchivan are mainly found in the districts of Sadarak and Teyvaz.[111] The remaining Armenians were expelled by Azerbaijani forces during the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh as part of the forceful exchange of population between Armenia and Azerbaijan. According to a 1932 Soviet estimate, 85% of the area's population was rural, while only 15% was urban. This urban percentage increased to 18% by 1939 and 27% by 1959.[17] As of 2011, 127,200 people of Nakhchivan's total population of 435,400 live in urban areas, making the urban percentage 29.2%.[112]

Nakhchivan enjoys a high Human Development Index; its socio-economic prowess far exceeds that of the neighbouring countries except for Turkey, as well as Azerbaijan itself. According to the report of Nakhchivan AR Committee of Statistics on June 30, 2014, for the end of 2013, some socio-economical data, including the following, are unveiled:

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Population | 452,831[112] |

| GNI (PPP) per Capita | $15,300[113] |

| Life Expectancy at Birth | 76.1 years[114] |

| Mean Years of Schooling | 11.2 years[115] |

| Expected Years of Schooling | 11.8 years[115] |

Making use of the Human Development Index calculation method according to the new UNHD 2014 method,[116] the above values change into these:

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Income Index | 0.7599 |

| Life Expectancy Index | 0.8630 |

| Education Index | 0.7011 |

Further, the value of the HDI becomes to

Were it a country, Nakhchivan would be ranked between Malaysia (62nd)[116] and Mauritius (63rd)[116] for its HDI. Iran's HDI is 0.749 (75th), Turkey's 0.759 (69th), and Azerbaijan's 0.747 (76th).[116]

Geography

Nakhchivan is a

Nakhchivan is

Both the absolute minimum temperature (−33 °C or −27.4 °F) and the absolute maximum temperature (46 °C or 114.8 °F) were observed in Julfa and Ordubad.[118]

Economy

Industry

Nakhchivan's major

The Republic is rich in minerals. Nakhchivan possesses deposits of

Although intentions to facilitate tourism have been declared by the government, it is still at best incipient. Until 1997 tourists needed special permission to visit, which has now been abolished, making travel easier. Facilities are very basic and heating fuel is hard to find in the winter, but the arid mountains bordering Armenia and Iran are magnificent. In terms of services, Nakhchivan offers very basic facilities and lacks heating fuel during the winter.[32]

In 2007 the

International issues

Destruction of Armenian cultural monuments

The number of named Armenian churches known to have existed in the Nakhchivan region is

When the 14th-century church of St. Stephanos at

The most publicised case of mass destruction concerns gravestones at a medieval cemetery in

In April 2006 British The Times wrote about the destruction of the cemetery in the following way:A Medieval cemetery regarded as one of the wonders of the Caucasus has been erased from the Earth in an act of cultural vandalism likened to the Taleban blowing up the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan in 2001. The Jugha cemetery was a unique collection of several thousand carved stone crosses on Azerbaijan's southern border with Iran. But after 18 years of conflict between Azerbaijan and its western neighbour, Armenia, it has been confirmed that the cemetery has vanished."[128]

Armenians have long sounded the alarm that the Azerbaijanis intend to eliminate all evidence of Armenian presence in Nakhchivan and to this end, have been carrying out massive and irreversible destruction of Armenian cultural traces. "The irony is that this destruction has taken place not during a time of war but at a time of peace," Armenian Foreign Minister Vartan Oskanian told The Times.[128] Azerbaijan has consistently denied these accusations. For example, according to the Azerbaijani ambassador to the US, Hafiz Pashayev, the videos and photographs "show some unknown people destroying mid-size stones", and "it is not clear of what nationality those people are", and the reports are Armenian propaganda designed to divert attention from what he claimed was a "state policy (by Armenia) to destroy the historical and cultural monuments in the occupied Azeri territories".[129]

A number of international organizations have confirmed the complete destruction of the cemetery. The Institute for War and Peace Reporting reported on April 19, 2006, that "there is nothing left of the celebrated stone crosses of Jugha."[130]

According to the International Council on Monuments and Sites (Icomos), the Azerbaijan government removed 800 khachkars in 1998. Though the destruction was halted following protests from UNESCO, it resumed four years later. By January 2003 "the 1,500-year-old cemetery had completely been flattened" according to Icomos.[131][132] On December 8, 2010, the American Association for the Advancement of Science released a report entitled "Satellite Images Show Disappearance of Armenian Artifacts in Azerbaijan".[133] The report contained the analysis of high resolution satellite images of the Julfa cemetery, which verified the destruction of the khachkars.

The European Parliament has formally called on Azerbaijan to stop the demolition as a breach of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention.[134] According to its resolution regarding cultural monuments in the South Caucasus, the European Parliament "condemns strongly the destruction of the Julfa cemetery as well as the destruction of all sites of historical importance that has taken place on Armenian or Azerbaijani territory, and condemns any such action that seeks to destroy cultural heritage."[135] In 2006, Azerbaijan barred a Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) mission from inspecting and examining the ancient burial site, stating that it would only accept a delegation if it also visited Armenian-occupied territory. "We think that if a comprehensive approach is taken to the problems that have been raised," said Azerbaijani foreign ministry spokesman Tahir Tagizade, "it will be possible to study Christian monuments on the territory of Azerbaijan, including in the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic."[136]

A renewed attempt was planned by PACE inspectors for August 29 – September 6, 2007, led by British MP Edward O'Hara. As well as Nakhchivan, the delegation would visit Baku, Yerevan, Tbilisi, and Nagorno Karabakh.[137] The inspectors planned to visit Nagorno Karabakh via Armenia; however, on August 28, the head of the Azerbaijani delegation to PACE released a demand that the inspectors must enter Nagorno Karabakh via Azerbaijan. On August 29, PACE Secretary-General Mateo Sorinas announced that the visit had to be cancelled because of the difficulty in accessing Nagorno Karabakh using the route required by Azerbaijan. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Armenia issued a statement saying that Azerbaijan had stopped the visit "due solely to their intent to veil the demolition of Armenian monuments in Nakhijevan".[138]

In 2022, the Cornell University-led monitoring group Caucasus Heritage Watch released a report detailing the "complete destruction of Armenian cultural heritage" in Nakhchivan starting the 1990s.[139] According the report, out of 110 medieval and early modern Armenian monasteries, churches and cemeteries identified from archival sources, 108 were deliberately and systematically destroyed between 1997 and 2011.[139] In some cases, such as the Saint Thomas Monastery in Yukhari Aylis (Agulis), mosques or other civic buildings were built on the site of the destroyed buildings.[139]

Recognition of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

In the late 1990s the

Culture

Nakhchivan is one of the cultural centers of Azerbaijan.[

- که تا جایگه یافتی نخچوان

- Oh Nakhchivan, respect you've attained,

- بدین شاه شد بخت پیرت جوان

- With this King in luck you'll remain.

Archaeology

The very early

The Naxçivan Archaeological Project is the first-ever joint American-Azerbaijani program of surveys and excavations, that was active since 2006.[146] In 2010–11, they have excavated the large Iron Age fortress of Oğlanqala.[147]

In Nakhchivan, there are also numerous archaeological monuments of the early Iron Age, and they shed a lot of light on the cultural, archaeological and agricultural developments of that era. There are important sites such as Ilikligaya, Irinchoy, and the Sanctuary of Iydali Piri in Kangarli region.[148]

Notable people

Political leaders

- Heydar Aliyev, former President of Azerbaijan (1993–2003).

- Abulfaz Elchibey, former President of Azerbaijan (1992–1993).

- National Assembly of Azerbaijan(1993–1996) and opposition leader.

- Christapor Mikaelian, founding member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation.

- Stepan Sapah-Gulian, leader of the Armenian Social Democrat Hunchakian Party (19th–20th century).

- Garegin Nzhdeh, famous Armenian revolutionary, military leader and political thinker.

- Supreme Assemblyof the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic.

Religious leaders

- Alexander Jughaetsi (Alexander I of Jugha), Catholicos of All Armenians (1706–1714).

Military leaders

- Abdurahman Fatalibeyli, Soviet army major who defected to the German forces during World War II.

- Ehsan Khan Nakhchivanski, Russian military general.

- Russian Tsar.

- Ismail Khan Nakhchivanski, Russian military general.

- Kelbali Khan Nakhchivanski, Russian military general.

- Jamshid Khan Nakhchivanski, Soviet and Azerbaijani military general.

- Yusif Mirzayev, National Hero of Azerbaijan.

- Maharram Seyidov, National Hero of Azerbaijan.

- Kerim Kerimov, National Hero of Azerbaijan.

- Sayavush Hasanov, National Hero of Azerbaijan.

- Mirasgar Seyidov, National Hero of Azerbaijan.

- Ali Mammadov, National Hero of Azerbaijan.

- Ibrahim Mammadov, National Hero of Azerbaijan.

- Amiraslan Aliyev, National Hero of Azerbaijan.

Writers and poets

- Huseyn Javid Rasizade, poet and playwright.

- Jalil Mammadguluzadeh, writer and satirist.

- Mammed Said Ordubadi, writer.

- Mammad Araz, poet.

Scientists

- Alec (Alirza) Rasizade, an American professor of history and political science, the author of the Rasizade's algorithm.

- Ruben Orbeli, Soviet archaeologist, historian and jurist, who was renowned as the founder of Soviet underwater archaeology.

Others

- Bahruz Kangarli, Azerbaijani painter.

- Haji Aliyev, Wrestling, World and European champion.

- International Master and Grandmaster.

- Ajami Nakhchivani, architect and founder of the Nakhchivan school of architecture.

- Gaik Ovakimian, Soviet Armenian spy.

- Ibrahim Safi, Turkish artist.

- Natavan Gasimova, volleyball player

- Rza Tahmasib, Azerbaijani film director.

Gallery

-

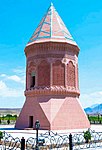

Brickwork and faience pattern on the Momine Khatun mausoleum

-

Medieval-period ram-shaped grave monuments collected near the Momine Khatun mausoleum

-

Ram-shaped grave monument embedded in concrete

-

The Batabat region of Shakhbuz

-

General view ofOrdubad with a range of high mountains in neighboring Iranin the distance

-

Houses in Ordubad photographed near the east bank of Ordubad-chay (also known as the Dubendi stream)

-

Narrow streets in Ordubad

-

A mosque in a quarter of Ordubad

-

Aras Riveron the Iranian border near Julfa

-

Mountainous terrain of Nakhchivan

See also

- List of Chairmen of the Supreme Majlis of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

- Nakhchivan Memorial Museum

- Nakhchivan culture

- Thamanin in southeast Turkey

References

- Notes

- ^ border 221 km (137 mi)

- ^ border 179 km (111 mi)

- ^ border 8 km (5.0 mi)

- ^ "As of today, the old frontiers between Armenia and Azerbaijan are declared to be non-existent. Mountainous Karabakh, Zangezur and Nakhchivan are recognised to be integral parts of the Socialist Republic of Armenia."[6][7]

- ^ The Nakhichevan uezd did not include the population of the Sharur or Sadarak districts which were part of the Sharur-Daralayaz and Erivan uezds, respectively.

- References

- ^ Xəlilzadə, elgunkh, Elgun Xelilzade, Elgun Khalilzadeh, Elgün. "Naxçıvan Muxtar Respublikası Dövlət Statistika Komitəsi". Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Naxcivan, | History & Geography | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- ^ Official portal of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic :Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic Archived December 9, 2012, at archive.today

- ^ "Population of Azerbaijan". stat.gov.az. State Statistics Committee. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ a b De Waal. Black Garden, p. 129.

- ^ Tim Potier, "Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia: A Legal Appraisal" (2001), p. 4.

- ^ Michael P. Croissant, "The Armenia–Azerbaijan Conflict: Causes and Implications" (1998), p. 18.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-57799-3

- ^ a b c Armenia: A Country Study: The New Nationalism, The Library of Congress

- ^ Andrew Andersen, PhD Atlas of Conflicts: Armenia: Nation Building and Territorial Disputes: 1918–1920

- ^ Croissant. Armenia–Azerbaijan Conflict, p. 16.

- ^ "Naxcivan – republic, Azerbaijan". Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ISBN 0-87779-809-5) New York: Merriam-Webster, Inc.

- ^ "Azerbaijan – history – geography". Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "Plant Genetic Resources in Central Asia and Caucasus: History of Armenia". Archived from the original on February 28, 2007.

- ^ Tabrizi, Yusuf S (2011). The Yazeris: The People, Their History and Culture. Tabriz: Self.

- ^ ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- ^ a b Elisabeth Bauer, Armenia: Past and Present, p.99 (ISBN B0006EXQ9C).

- ISBN 0-8305-0076-6).

- ^ Ibid. p.267.

- ^ a b (in Russian) "Nakhichevan" in the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, St. Petersburg, Russia: 1890–1907.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 156.

- ^ a b c Hiwbshman, H. (1907). Hin Hayotsʻ Teghwoy Anunnerě [Ancient Armenian Place Names] (in Armenian). Translated by Pilējikchean, H. B. Vienna: Mkhitʻarean Tparan. pp. 222–223, 385.

- ^ Hakobyan, T. Kh.; Melik-Bakhshyan, St. T.; Barseghyan, H. Kh. (1991). "Nakhijevan". Hayastani ev harakitsʻ shrjanneri teghanunneri baṛaran [Dictionary of toponymy of Armenia and adjacent territories] (in Armenian). Vol. 3. Yerevan State University. pp. 951–953.

- ^ ISBN 3-88226-485-3.

- ^ "Chapter 3". Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Noah's Ark: Its Final Berth Archived March 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine by Bill Crouse

- ^ "Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic". nakhchivan.preslib.az. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- .

- S2CID 251329025.

- ISBN 978-2-35668-074-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Нахичеванская Автономная Советская Социалистическая Республика, Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- ^ "Early Indo-European Online: Introduction to the Language Lessons". Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ ISBN 0-8143-1896-7

- ^ Hewsen. Armenia: A Historical Atlas, p. 100.

- ^ (in Armenian) Ter-Ghevondyan, Aram. "Մուրացյան" (Muratsyan). Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia. vol. viii. Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1982, p. 98.

- ^ "ARMENIA". Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Կորյուն, Վարք Մաշտոցի, աշխարհաբար թարգմանությունը, ներածական ուսումնասիրությամբ, առաջաբանով և ծանոթագրություններով՝ Մ. Աբեղյանի, Եր., 1962, էջ 98։

- ^ Koryun: Life of Mashtots Koryun, The Life of Mashtots

- ^ ISBN 0-04-956009-3.

- ISBN 0-520-20497-2

- ^ M. Whittow, "The Making of Byzantium: 600–1025", pp. 195, 203, 215: Excerpts:[Iranian] Azerbaijan was the scene of frequent anti-Caliphate and anti-Arab revolts during the eighth and ninth centuries, and Byzantine sources talk of Persian warriors seeking refuge in the 830s from the caliph's armies by taking service under the Byzantine emperor Theophilos. [...] Azerbaijan had a Persian population and was a traditional centre of the Zoroastrian religion. [...] The Khurramites were a [...] Persian sect, influenced by Shiite doctrines, but with their roots in a pre-Islamic Persian religious movement.

- ^ Armenian historian Vardan Areveltsi, c. 1198 – 1271 notes: In these days, a man of the PERSIAN race, named Bab, who had went from Baltat killed many of the race of Ismayil (what Armenians called Arabs) by sword and took many slaves and thought himself to be immortal. ..Ma'mun for 7 years was battling in the Greek territories and ..came back to Mesopotamia. See: La domination arabe en Armènie, extrait de l’ histoire universelle de Vardan, traduit de l’armènian et annotè, J. Muyldermans, Louvain et Paris, 1927, pg 119: En ces jours-lá, un homme de la race PERSE, nomm é Bab, sortant de Baltat, faiser passer par le fil de l’épée beaucoup de la race d’Ismayēl tandis qu’il.. Original Grabar: Havoursn haynosig ayr mi hazkes Barsitz Pap anoun yelyal i Baghdada, arganer zpazoums i sour suseri hazken Ismayeli, zpazoums kerelov. yev anser zinkn anmah. yev i mium nvaki sadager yeresoun hazar i baderazmeln youroum ent Ismayeli

- ^ Ibn Hazm (994–1064), the Arab historian mentions the different Iranian revolts against the Caliphate in his book Al-fasl fil al-Milal wal-Nihal. He writes: The Persians had the great land expanse and were greater than all other people and thought of themselves as better... after their defeat by Arabs, they rose up to fight against Islam, but God did not give them victory. Among their leaders were Sanbadh, Muqanna', Ostadsis and Babak and others. Full original Arabic:

- «أن الفرس كانوا من سعة الملك وعلو اليد على جميع الأمم وجلالة الخطير في أنفسهم حتى أنهم كانوا يسمون أنفسهم الأحرار والأبناء وكانوا يعدون سائر الناس عبيداً لهم فلما امتحنوا بزوال الدولة عنهم على أيدي العرب وكانت العرب أقل الأمم عند الفرس خطراً تعاظمهم الأمر وتضاعفت لديهم المصيبة وراموا كيد الإسلام بالمحاربة في أوقات شتى ففي كل ذلك يظهر الله سبحانه وتعالى الحق وكان من قائمتهم سنبادة واستاسيس والمقنع وبابك وغيرهم ». See: al-Faṣl fī al-milal wa-al-ahwāʾ wa-al-niḥal / taʾlīf Abī Muḥammad ʻAlī ibn Aḥmad al-maʻrūf bi-Ibn Ḥazm al-Ẓāhirī; taḥqīq Muḥammad Ibrāhīm Naṣr, ʻAbd al-Raḥmān ʻUmayrah. Jiddah : Sharikat Maktabāt ʻUkāẓ, 1982.

- ^ "Babak". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica, "Atabakan-e Adarbayjan" Archived October 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Saljuq rulers of Azerbaijan, 12th–13th, Luther, K. pp. 890–894.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "The mausoleum of Nakhichevan (#) – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica. C. Bosworth. History of Azerbaijan, Islamic period to 1941, page 225[permanent dead link]

- ^ Floor 2008, p. 171.

- ^ The Status of Religious Minorities in Safavid Iran 1617–61, Vera B. Moreen, Journal of Near Eastern Studies Vol. 40, No. 2 (April 1981), pp.128–129

- ^ The history and conquests of the Saracens, 6 lectures, Edward Augustus Freeman, Macmillan (1876) p. 229

- ^ Lang. Armenia: Cradle of Civilization, pp. 210–1.

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica. Kangarlu Archived October 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ISBN 1598849484

- ^ Туркманчайский договор 1828, Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- ^ (in Russian) A.S. Griboyedov. Letter to Count I.F.Paskevich.

- ^ (in Russian) Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary. "Sharur-Daralagyoz uyezd". St. Petersburg, Russia, 1890–1907

- ISBN 0-275-96241-5

- ^ Croissant. Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Dr. Andrew Andersen, PhD Atlas of Conflicts: Armenia: Nation Building and Territorial Disputes: 1918–1920

- ISBN 0-8147-1945-7

- ^ Croissant. Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict, p. 16.

- ^ ISBN 978-0190869663.

- ISBN 978-0190869663.

- ^ ISBN 90-411-1477-7

- ^ Croissant. Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict, p. 18.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-57799-3

- ^ "ANN/Groong – Treaty of Berlin – 07/13/1878". Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ De Waal. Black Garden, p. 271.

- ISBN 0-275-97260-7

- ISBN 0-8014-8736-6

- ^ De Waal, Black Garden, p. 88-89.

- ISBN 9780391037724.

- ^ William, Nick B. Jr. (January 21, 1990). "Soviet Enclave Declares Independence". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ISBN 9780812920468.

- ^ "Asian Event/USSR". Asian Bulletin. Vol. 15, no. 1–6. Taiwan: APACL Publications. 1990. p. 73. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ISBN 9780230590489.

- ^ "Iranian Influence in Nakhchivan: Impact on Azerbaijani-Armenian Conflict". Jamestown.

- ^ Azerbaijan: A Country Study: Aliyev and the Presidential Election of October 1993, The Library of Congress

- ^ Contested Borders in the Caucasus: Chapter VII: Iran's Role as Mediator in the Nagorno-Karabakh Crisis Archived February 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine by Abdollah Ramezanzadeh

- ^ Russia Plans Leaner, More Open Military. The Washington Post. May 23, 1992

- ^ Background Paper on the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict. Council of Europe.

- ^ The Toronto Star. May 20, 1992

- ^ a b "US Department of State Daily Briefing #78: Tuesday, 5/19/92". Archived from the original on September 8, 2006. Retrieved January 12, 2007.

- ^ Armenian Siege of Azeri Town Threatens Turkey, Russia, Iran. The Baltimore Sun. June 3, 1992

- ^ Reuters News Agency Archived January 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, wire carried by the Globe and Mail (Canada) on May 20, 1992. pg. A.10

- ^ a b Overview of Areas of Armed Conflict in the former Soviet Union, Human Rights Watch, Helsinki Report

- ^ Azerbaijan: Seven Years Of Conflict In Nagorno-Karabakh, Human Rights Watch, Helsinki Report

- ^ a b Turkey Orders Armenians to Leave Azerbaijan, Moves Troops to the Border. The Salt Lake Tribune. September 4, 1993. pg. A1.

- ^ Azerbaijan: A Country Study: Efforts to Resolve the Nagorno-Karabakh Crisis, 1993, The Library of Congress

- ISBN 1-74059-138-0

- ^ "State Structure of Nakhchivan". Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Nakhichevan: Disappointment and Secrecy". Institute for War and Peace Reporting. May 19, 2004. Retrieved May 19, 2004.

- ^ "Nakhichevan: From Despair to Where?". Axis News. July 21, 2005. Archived from the original on January 12, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2005.

- ^ "Azerbaijani President attends opening of bridge uniting Iran with Azerbaijan". Azeri Press Agency. October 17, 2007. Archived from the original on October 21, 2007. Retrieved January 3, 2008.

- ^ "Statement by President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia and President of the Russian Federation". Kremlin.ru. November 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Official portal of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic :Cities and regions Archived May 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hewsen. Armenia: A Historical Atlas, p. 123.

- ^ Alexander Griboyedov (1828). Рапорт А.С.Грибоедова графу И.Ф.Паскевичу (in Russian). Moscow: А.С.Грибоедов. Сочинения. Москва, Художественная литература, 1988 г., сс. 611–614.

- ^ Ivan Shopen (1852). Шопен И. Исторический памятник состояния Армянской области в эпоху её присоединения к Российской Империи. [Ethnic Processes in the South Cacucasus in 19th–20th centuries] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Имп. Академия наук (Imperial Academy of Sciences).

- ^ (in Russian) Нахичевань. Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary

- ^ (in Russian) Демокоп Weekly Нахичеванский уезд

- ^ Кавказский календарь на 1917 год [Caucasian calendar for 1917] (in Russian) (72nd ed.). Tiflis: Tipografiya kantselyarii Ye.I.V. na Kavkaze, kazenny dom. 1917. pp. 214–221. Archived from the original on November 4, 2021.

- ^ Christopher J. Walker, ed., Armenia and Karabakh, op. cit., pp. 64–65

- ^ "Нахичеванская ССР 1926". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru (in Russian).

- ^ a b c d e (in Russian) Население Азербайджана

- ^ "The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan – Regions of Azerbaijan- Nakchivan economic district – Ethnic Structure". Archived from the original on February 13, 2012.

- ^ "Ethnic composition of Azerbaijan 2009". Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "Naxçıvan əhalisinin sayı açıqlandı". May 22, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2018 – via qafqazinfo.az.

- ^ "The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan: Nakhchivan Economic Region". Archived from the original on February 13, 2012.

- ^ "Kurdish people – Kurds in Azerbaijan – Azerb.com".

- ^ a b "Naxçıvan Muxtar Respublikası üzrə əhalinin sayı və cins üzrə bölgüsü 1)". Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Makroiqtisadi göstəricilər". statistika.nmr.az. Archived from the original on December 1, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Naxçıvan Muxtar Respublikası üzrə cins bölgüsündə doğulanda gözlənilən ömür uzunluğu". Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ a b "Naxçıvan Muxtar Respublikası üzrə təhsilin əsas göstəriciləri". Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Technical notes: Calculating the human development indices – graphical presentation" (PDF). June 24, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ Plunkett and Masters. Lonely Planet, p. 246.

- ^ Mahmudov, Rza. "Water Resources of the Azerbaijan Republic". Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Azerbaijan Republic. Archived from the original on May 24, 2007. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ^ "USACC Newsletter". usacc.org. Archived from the original on March 16, 2018. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ Alexande de Rhodes, Divers Voyages et Missions du P. A. de Rhodes en la Chine, &AutresRoyaumes avec son Retour en Europe par la Perse et I’Armenie (Paris: Sebastian Cramoisy, 1653), Part 3, 63. Second edition (Paris: 1854), 416. "Out of the walls of this city [Julfa] which now is only a desert, I saw a beautiful monument to the ancient piety of the Armenians. It is a vast site, where there are at the very least ten thousand tombstones of marble, all marvellously well carved."

- ^ Sylvain Besson, "L'Azerbaidjian Face au Desastre Culturel", Le Temps (Switzerland), November 4, 2006.

- ^ Switzerland-Armenia Parliamentary Group (ed.) "The destruction of Jugha and the Entire Armenian Cultural Heritage in Nakhchivan", Bern, 2006. p73-77.

- ^ Monumental Effort: Scotsman wants to prove Azeri policy of cultural destruction in Nakhijevan, Gayane Mkrtchyan, ArmeniaNow, September 2, 2005.Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Quote: "But a special state policy of destruction is being implemented in Azerbaijan. In Turkey, after 90 years of staying empty, there are still standing churches today, meanwhile in Nakhijevan, all have been destroyed within just 10 years."

- ^ The Switzerland-Armenia Association (SAA), for consideration at the 49th session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Pre-Sessional Working Group, 21–25 May 2012)

- ^ "World Watches in Silence As Azerbaijan Wipes Out Armenian Culture". The Art Newspaper. May 25, 2006. Archived from the original on September 11, 2006. Retrieved May 25, 2006.

- ^ "Tragedy on the Araxes". Archaeology. June 30, 2006. Retrieved June 30, 2006.

- ^ "Armenica: Destruction of Armenian Khatchkars in Old Jougha (Nakhichevan)". Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ a b "Historic graveyard is victim of war – The Times". The Times. Archived from the original on June 27, 2015. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "Will the arrested minister become new leader of opposition? Azerbaijani press digest". REGNUM News Agency. January 20, 2006. Retrieved January 20, 2006.

- ^ "Azerbaijan: Famous Medieval Cemetery Vanishes". Institute for War and Peace Reporting. April 19, 2006. Retrieved April 19, 2006.

- ^ ICOMOS World Report 2006/2007 on Monuments and Sites in Danger

- Independent.co.uk. May 29, 2006. Archivedfrom the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "Satellite Images Show Disappearance of Armenian Artifacts in Azerbaijan". December 8, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "European Parliament Resolution on the European Neighbourhood Policy – January 2006". Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "Texts adopted – Thursday, 16 February 2006 – Cultural heritage in Azerbaijan – P6_TA(2006)0069". Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Castle, Stephen (May 30, 2006). "Azerbaijan 'Flattened' Sacred Armenian Site". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved May 30, 2006.

- ^ "Pace Mission to Monitor Cultural Monuments", S. Agayeva, Trend News Agency, Azerbaijan, August 22, 2007.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Armenia, Press Release August 29, 2007.

- ^ a b c Nutt, David (September 12, 2022). "Report shows near-total erasure of Armenian heritage sites". Cornell Chronicle. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ "iExplore.com – Cyprus Overview". Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2007.

- ^ "Europe, the US, Turkey and Azerbaijan recognize the "unrecognized" Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus". REGNUM News Agency. September 22, 2006. Retrieved September 22, 2006.

- ^ "Teatrlar". imp.nakhchivan.az. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Family tree". Virtual Museum of Aram Khachaturian. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ISBN 9789993051299.

- ^ Bakhshaliev V.B. (2013), Proto Kura-Araxes ceramics of Nakhchivan

- ^ Nakhchivan Archaeological Project oglanqala.net

- ^ 2010 / 2011 Season oglanqala.net

- ^ Archaeological Treasures Of Nakhchivan – OpEd – Eurasia Review 2016

Sources

- Floor, Willem M. (2008). Titles and Emoluments in Safavid Iran: A Third Manual of Safavid Administration, by Mirza Naqi Nasiri. Washington, DC: Mage Publishers. p. 248. ISBN 978-1933823232.

Further reading

- Dan, Roberto (2014). "Inside the Empire: Some Remarks on the Urartian and Achaemenid Presence in the Autonomous Republic of Nakhchivan". Iran and the Caucasus. 18 (4): 327–344. .