Nandi people

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 937,884 (2019) African Traditional Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kalenjin and other Nilotes |

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (May 2021) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Kenya |

|---|

|

|

Cuisine |

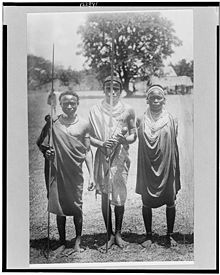

The Nandi are part of the

Etymology

Before the mid-19th century, the Nandi referred to themselves as Chemwalindet (pl. Chemwalin) or Chemwal (pl. Chemwalek)[2] while other Kalenjin-speaking communities referred to the Nandi as Chemngal.[3] It is unclear where the terms originated from, though in early writings the latter term was associated with ngaal which means camel in Turkana and suggestions made that the name could be an "...allusion to the borrowing, direct or indirect of the rite of circumcision from camel riding Muslims".[3] Later sources do not make similar suggestions or references to this position.

The name Nandi came into use after the mid-19th century and more so after the defeat of the Uasin Gishu and the routing of the Swahili and Arab traders.[4] The name is thought to derive from the similarity of the rapaciousness of the warriors of the mid-1800s to the habits of the voracious cormorant which is known as mnandi in Kiswahili.[5]

Nandi position and facet to Kalenjin

The Nandi people are one among a group of communities that share cultural traits and a Southern Nilotic language known as

The Kalenjin languages are broadly similar with most of the dialects being mutually intelligible. The Nandi use Kalenjin nomenclature, which is similar across most communities apart from the Marakwet where names of persons may be inverted gender-wise; certain folklore indicates that this may have been as a result of a genocide that targeted either the males or females of Marakwet. Kalenjin mythology was broadly similar and is thought to have stemmed from an earlier worship oriented at the sky, later turning its focus of worship to the sun. This change may have radiated from the Kibasisek clan originally from Marakwet. Today most Nandi are either Protestant Christian or Catholic as are most Kalenjin.

The Nandi experience contributes a great deal to commonly perceived Kalenjin heritage as well as to contemporary Kalenjin culture. Many customs are shared across Kalenjin communities though circumcision is absent in some communities. Kalenjin can traditionally marry from within Kalenjin as if it were within each individual's community. Oret (clan) membership cuts across the various communities with Nandi and Kipsigis ortinwek ties being particularly intricate thus making both seem as a single identity even to date.

History

A totality of various traditions making up the narrative of the Settlement of Nandi seem to date the origin of a differentiated Nandi identity to the early decades of the nineteenth century and no later than the latter decades of the eighteenth century. The development of the Nandi identity is intrinsically linked to the settlement of Nandi County.

19th century

Settlement of Nandi

Within Nandi tradition, the existence of a differentiated Nandi identity is understood as a distinct process through which various Kalenjin and Maa-speaking clans came to occupy the present day Nandi county. The traditional Nandi account is that the first settlers in their country came from Elgon during the time of the Maina[definition needed] and formed the Kipoiis clan; a name that possibly means 'the spirits'. They were led by a man named Kakipoch, founder of the Nandi section of the Kalenjin and are said to have settled in the emet (county) of Aldai in south-western Nandi.

Studies of the settlement pattern indicate that the southern regions were the first to be settled, the emet of Aldai on the west and the emet of Soiin on the east, being the first to be established. It has been conjectured that the first pororosiek were Kakipoch in Aldai and Tuken in Soiin.[6]

It is notable that

Emotinua development

Inward migrants and general population growth are conjectured to have led to a northward expansion of the growing identity during the eighteenth century. This period is thought to have seen the occupation and establishment of the emotinwek of Chesume, Emgwen and Masop. This period would also have seen the establishment of more pororosiek.[6]

The final expansion would occur during the middle of the nineteenth century when the Nandi took the Uain Gishu plateau from the Uasin Gishu.

Emotinua organization

The emotinwek system of territorial organisation was broadly similar to that of other Kalenjin communities. The Nandi territory was by the turn of the century divided into six counties known as emet (pl. emotinua/emotinwek). These were Wareng, located to the north, Mosop in the northeast, Tindiret in the east, Soiin and Pelkut in the south, Aldai and Chesumei in the west and Emgwen in the center. The emotinwek were divided into districts known as bororiet (borororisiek) and these were divided into villages known as kokwet (kokwotinwek). The Nandi administrative system was unique among the Kalenjin in having the bororiosiek administrative layer.

Within the wider Kalenjin administrative system, the Kokwet was the most significant political and judicial unit in terms of day to day issues. The kokwet elders were the local authority for allocating land for cultivation, they were also the body to whom the ordinary member of the tribe would look for a decision in a dispute or problem which defied solution by direct agreement between the parties. Membership of the kokwet council was acquired by seniority and personality and within it decisions were taken by a small number of elders whose authority derived from their natural powers of leadership. Among the Nandi however, the Bororiet was the most significant institution and the political system revolved around it.

Cultural development

The Nandi of the nineteenth century were a primarily martial community and little cultural development was experienced for much of this period. Hollis (1905) for instance observed that "the art of music has not reached a very advanced stage in Nandi".

The social climate (see First Mutai and Second Mutai) led to the development of a learning system known as Kamuratanet that principally revolved around preparation for warfare, both defensive and offensive. It divided the male sex into boys, warriors and elders while the female sex is divided into girls and married women. The first stage began at birth and continued until initiation.

All boys who were circumcised together were said to belong to the same ibinda (age set) and once the young men of a particular ibinda came of age, they were tasked with protecting the tribal lands and the society, the period when they were in charge of protection of the society was known as the age of that ibinda. The Kalenjin have eight cyclical age-sets or ibinwek, however the Nandi dropped the korongoro at some point as a result of disaster. Legend has it that the members of this ibinda were wiped out in war. This was because they were told not to go for that war but they could not listen. It is said they, that ibinda, the korongoro put on their ears some septook (broken pieces of calabashes) to avoid listening to the wise words of the Orkoiyot. During the war they were unsuccessful. For fear of a recurrence, the community decided to retire the age-set.

Mid-19th century

Nandi identity

The earliest recorded mention of Arab

The Nandi warriors had never encountered a foe armed with firearms before and they had to develop new military tactics to overcome the effectiveness of a large number of firearms. Like the Masai, the warriors drew the enemy's fire by a sudden rush at which time they went "go to ground." Then the warriors charged the caravan porters before the muzzle loading weapons could be recharged. The porters bolted into the reloading riflemen followed closely by the Nandi warriors and in this confusion, the Nandi warriors could spear the panicked men. This tactic would be deployed effectively until the battle of Kimondi in 1895.

Part of the reason for the Nandi success was the limited access. The easiest approach was from the north-east, but a caravan had to travel two or three days before reaching principal Nandi settlements. This evidently was not preferable as the Arab caravans diverted east to Kavirondo and Mumias where food and protection was located.

Due to the casualties to the caravans, direct trade increasingly became difficult. Caravans rarely entered or camped in Nandi and a strange "middle man" system evolved after the 1850s. Trusted Sotik and Dorobo agents were employed to act as "middle men" who would trade ivory and other coastal goods for cattle to the Nandi for a large commission.[4]

"Enterprising Arab traders hoping to circumvent this arrangement often fell victims to a Nandi ploy. A few old Nandi warriors would meet the armed caravan and tell them that a large supply of ivory was only two or three days journey from the caravan. However, the Nandi were only willing to entertain a small Arab party to negotiate a trade. Dutifully, a party of twenty men would be dispatched with cloth, wire, and other trade goods only to be ambushed by the Nandi and massacred." "Another ruse used by the Nandi was to send a small party of warriors to lead the prospective caravan into the depths of Nandi by the wrong road and then conduct a night attack. The Arab traders even attempted a tactic that had worked with other tribes,

Frustrated by failures, the Arab traders attempted one last tactic. They established a series of fortified stations at Kimatke, Kibigori, Chemelil, Kipsoboi, and Kobujoi, and began a campaign of intimidation. Donkeys were let loose to trample the millet fields, Nandi warriors were humiliated, Nandi boys were imprisoned, and Nandi women and girls were raped. At Kipsoboi four Nandi shields were propped against a tree and the Nandi were offered the chance to shoot arrows into the shields. Once this was accomplished, the Arabs fired musket balls through the shields that had stopped the arrows. The Arabs then poured gruel over the attending Nandi's heads and shaved off their cherished locks.

The Nandi warriors had had enough. They sought permission from the Kaptalam Orkoiyot to kill the Arabs. He gave permission, and the post was stormed. Some accounts credit the Orkoiyot's charms with making the defender's ammunition disappear, while others credit the error of the garrison commander to provide ammunition to the riflemen. Regardless of the reason, the garrison at Kipsoboi was destroyed. The Nandi kiptaiyat (raiding bands) then successfully attacked and slaughtered the garrison at Kobujoi. This was enough to force the Arab traders to withdraw from Nandi and to avoid the area.

The defeat of the Arabs created the "Nandi legend." The Nandi were undefeatable. Porters could not be hired and expeditions could not be launched into Nandi for nearly forty years. The Nandi warriors stood proudly aloof from the events that were swirling around them confident to defend their independence.[4]

Late 19th-century

Nandi resistance

By the later decades of the 19th century, at the time when the early European explorers started advancing into the interior of Kenya, Nandi territory was a closed country Thompson in 1883 was warned to avoid the country of the Nandi, who were known for attacks on strangers and caravans that would attempt to scale the great massif of the Mau.[7]

Matson, in his account of the resistance, showed "how the irresponsible actions of two British traders, Dick and West, quickly upset the precarious modus vivendi between the Nandi and incoming British".[8] This would cause more than a decade of conflict led on the Nandi side by Koitalel Arap Samoei, the Nandi Orkoiyot at the time.

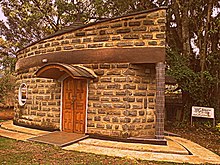

The conflict would end on 19 October 1905, when Col Richard Meinertzhagen called for a peace meeting. Instead, Meinertzhagen and his men killed Koitalel and his entourage on the grounds of what is now Nandi Bears Club.

Sosten Saina, grand-nephew of one of Arap Samoei's bodyguards notes that "There were about 22 of them who went for a meeting with the mzungu that day. Koitalel Arap Samoei had been advised not to shake hands because if he did, that would give him away as the leader. But he extended his hand and was shot immediately". Shortly after this event, the Nandi Resistance ended and Nandi was incorporated into the British East Africa Protectorate.[9]

20th century

World War I (1914-1918)

Official records of the K.A.R show that a total of 1,197 Nandi were recruited during the war. At the time the Nandi population is estimated to have been about 40–50,000 individuals. Most of those recruited were of the Nyongi age-set which had been initiated during the four-year period immediately preceding the war. Greenstein (1978) following interviews with veterans of the war found that participation in the war made little impact on the Nyongik, as or as agents-of-change, as regards adapting western methods. Neither did the earned wages seem to engender an affection for the formal economy nor was any effort made towards participation in the political process.[10]

Socially, the Nyongik had been initiated just prior to the wars, hence they left and returned unmarried. This did not disrupt ordinary patterns since it was more usual than unusual for young men to wait a few years before marriage. This time was spent searching for bride wealth, and serving in the war may be said to have served this purpose. Later interviews with veterans indicate that they were warmly welcomed back by parents and contemporaries. Neither did they bear resentment to their age-mates who had avoided the hardships of military service, some of who had married and acquired cattle in the intervening period. In fact, the veterans note that they expressed gratitude to them for looking after their cattle and other property as they had been slogging around

Economically, it is noted that the veterans did not receive pensions as they had expected but that they did return with their back-pay which for some amounted to as much as several hundred shillings, quite a significant sum at the time. It is noted that almost all of the returning veterans used their back pay to purchase cattle, some of which along with cash was used as bride wealth. There were instances of land purchase on the fringes of the reserve but these were minimal. Much as the Government had alienated part of the Nandi Reserve the population pressure was not yet great enough to leave most men dissatisfied with the amount of land they would acquire by traditional means. It has been observed that where purchases were made it was done less with entrepreneurial motive than as a desire to increase one's pasture land.[10]

There were also minimal changes to the employment patterns. Few Nandi previously found the prospect of paid employment sufficiently alluring to leave in search of jobs. For instance in 1914 only 100 out of a population of about 45,000 was employed outside the District. The numbers did rise to 352 for 1915/6 and 612 in 1916/7, largely in response to the wartime needs of the Protectorate but by 1919 they had fallen back to 185. While military service continued to appeal to the young men, civilian service did not. The District Commissioner was hard put in 1922 for instance to produce 200 able-bodied young men to work on a local road-building project. He would resort to conscripting them under the 'Native Authority Ordinance', the infamous labor circular written in 1919 by then B.E.A Governor Edward Northey.[10][11]

Politically, it is observed that the Nyongik assimilated back into the traditional power structure in much the same positions they had left some three or four years earlier. Within that structure, age and not stars and stripes counted for seniority. The obligations and ties they resumed were to their families, age-set and korotinwek meaning the common interests of veterans gave way to a man's traditional associations. Greenstein notes that the concept of a formal organisation of veterans appears either not to have occurred or perhaps not appealed to them. Even the pension issue did not impel the Nyongik to form any sort of coherent organization.[10]

Greenstein states that in the period following the War, the minority European civilian population resident in Kenya and the Protectorate Government, were worried about the possibility of armed insurrection among the indigenous peoples. He notes that one of the greatest fears of the Europeans, which he observes to have been true for both Wars, was that they had lost prestige in the eyes of Africans. He quotes Shiroya who was writing after the war to illustrate a then commonly held perception which was that "the ex-askari had learned and observed that without modern technology, a European was no better than an African". There was also a belief held by some "that blacks, having seen white men kill other white men, would sooner or later realize that they too could do the same". The latter states that "to make this argument is to suggest that Africans once regarded Europeans as superior, perhaps even as demi-gods". He counter-argues that "the evidence including armed primary resistance in many parts of the continent, and especially in Nandi, makes it seem very unlikely that this was ever the case".[10] Accounts by European adventurers in the 19th century, such as Thompson who spoke of having to deal with the 'overbearing' attitude of the Maasai seem to be in line with his assertion.[12] The introduction of the Maxim gun altered the power symmetry which Greenstein suggests was apparent to Africans hence "the deference showed, which some Europeans took as awe and respect".[10] This attitude has been commented upon outside Africa as well.[13]

The environment following the war was thus one in which the European population was worried about civilian unrest. Fears that appear to have been stoked by an upsurge in political activity in the 1920s, notably Archdeacon Owen's Piny Owacho (Voice of the People) movement and Harry Thuku's Young Kikuyu Association.

Nandi Protest of 1923

A number of factors taking place in the early 1920s led to what has come to be termed the Nandi Protest[14] or Uprisings of 1923. It was the first expression of organized resistance by the Nandi since the wars of 1905-06.

Primary contributing factors were the land alienation of 1920 and a steep increase in taxation, taxation tripled between 1909 and 1920 and because of a change in collection date, two taxes were collected in 1921. The Kipsigis and Nandi refused to pay and this amount was deferred to 1922. Further, due to fears of a spread of rinderpest following an outbreak, a stock quarantine was imposed on the Nandi Reserve between 1921 and 1923. The Nandi, prevented from selling stock outside the Reserve, had no cash, and taxes had to go unpaid. Normally, grain shortages in Nandi were met by selling stock and buying grain. The quarantine made this impossible. The labor conscription that took place under the Northey Circulars only added to the bitterness against the colonial government.

All these things contributed to a buildup of antagonism and unrest toward the government between 1920 and 1923. In 1923, the saget ab eito (sacrifice of the ox), a historically significant ceremony where leadership of the community was transferred between generations, was to take place. This ceremony had always been followed by an increased rate of cattle raiding as the now formally recognized warrior age-set sought to prove its prowess. The approach to a saget ab eito thus witnessed expressions of military fervour and for the ceremony all Nandi males would gather in one place.

Alarmed at the prospect and as there was also organized protest among the

Recent history

Culture

Sport

Like other Kalenjin, the Nandi have produced a number of notable Kenyan athletes. These include great distance athletes like Kipchoge Keino (Kip Keino), a gold medalist at Mexico (1968) and Munich (1972) Olympic games, and Prof. Mike Boit, a bronze medalist at Munich 1972 Olympics. Others include Peter Koech, Bernard Kipchirchir Lagat, and Wilson Kipketer, Pamela Jelimo, Wilfred Bungei, Richard Mateelong, Super Henry Rono, Peter Rono, Tecla Chemabwai, and Paralympian Henry Kirwa among others. The father of Kenyan steeplechasers Amos Kipwambok Biwott comes from the community as does Julius Yego, the first Kenyan to win a World Championships gold medal in a field event.

Janeth Chepkosgei and Eliud Kipchoge are also Nandi.

Politics

The Nandi people have had remarkable political figures like

Notable Nandi female politicians include Philomena Chelagat Mutai, a lifelong activist for the inclusion of women in Kenyan politics and society, and Sally Kosgei, a former MP for Aldai.

Notable Nandi

- William Samoei Ruto, fifth president of the Republic of Kenya

- Jackson Mandago, first governor and 2nd senator of Uasin Gishu County

- Stephen Sang, first senator and 2nd Governor of Nandi County

- Sally Kosgei, former minister of Agriculture.

- Henry Kosgey, former member of Parliament of Kenya and minister of industrialization

- Jean-Marie Seroney, former member of Parliament for Tinderet constituency

- Chelagat Mutai, former Eldoret North Member of Parliament

- Eliud Kipchoge, marathon runner

- Bernard Lagat, middle and long distance runner

References

- ^ "2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census Volume IV: Distribution of Population by Socio-Economic Characteristics". Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ A. C. Hollis. The Nandi: Their Language and Folklore. Clarendon Press: Oxford 1909, p.306

- ^ a b A. C. Hollis. The Nandi: Their Language and Folklore. Clarendon Press: Oxford 1909, p.xv

- ^ a b c d Bishop, D. Warriors in the Heart of Darkness: The Nandi Resistance 1850 to 1897, Prologue

- ^ Lagat, A. Arap, The historical process of Nandi movement into Uasin Gishu district of the Kenya highlands: 1906-1963, University of Nairobi online

- ^ a b c Museums Trustees of Kenya (1910). The Journal of the East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society. London: East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society. p. 7.

- ^ Pavitt, N. Kenya: The First Explorers, Aurum Press, 1989, p. 121

- ^ Nandi Resistance to British Rule 1890–1906. By A. T. Matson. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1972. Pp. vii+391

- ^ a b "Murder that shaped the future of Kenya". EastAfrican. 5 December 2008.

- ^ S2CID 154836832.

- JSTOR 40282490.

- ^ Thompson, Joseph (1887). Through Masai land: a journey of exploration among the snowclad volcanic mountains and strange tribes of eastern equatorial Africa. Being the narrative of the Royal Geographical Society's Expedition to mount Kenia and lake Victoria Nyanza, 1883-1884. London: S. Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington. pp. 206.

- ^ Ferriter, Diarmaid (4 March 2017). "Inglorious Empire: what the British did to India". The Irish Times. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Ellis, D. The Nandi Protest of 1923 in the Context of African Resistance to Colonial Rule in Kenya, The Journal of African History, Vol. 17, No 4 (1976)

- ^ Oboler, R.S, online[permanent dead link], Stanford University Press, 1985

Bibliography

- A. C. Hollis. The Nandi: Their Language and Folklore. Clarendon Press: Oxford 1909.

- Ember and Ember. Cultural Anthropology. Pearson Prentice Hall Press: New Jersey 2007.