Nataraja

| Nataraja | |

|---|---|

Lord of the dance | |

A 10th-century Chola dynasty bronze sculpture of Shiva, the Lord of the Dance at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art | |

| Other names | Adalvallan, Koothan, Sabesan, Ambalavanan[1] |

| Affiliation | Shiva |

| Symbols | Agni |

| Texts | Amshumadagama Uttarakamika agama |

| Part of a series on |

| Shaivism |

|---|

|

|

|

Nataraja (

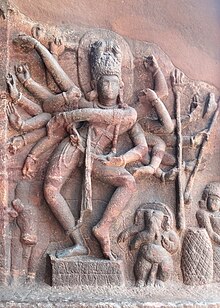

The sculpture is symbolic of Shiva as the lord of dance and dramatic arts,[13] with its style and proportions made according to Hindu texts on arts. Tamil devotional texts such as the Tirumurai (The twelve books of Southern Shaivism) state that Nataraja is the form of Shiva in which he performs his functions of creation, destruction, preservation, and is also attributed with maya and the act of blessing his devotees. Thus, Nataraja is considered one of the highest forms of Shiva in Tamil Nadu, and the sculpture or the bronze idol of Nataraja is worshipped in almost all Shiva temples across Tamil Nadu.[14] It typically shows Shiva dancing in one of the Natya Shastra poses, holding various symbols[14] which vary with historic period and region,[3][15] trampling upon a demon shown as a dwarf (Apasmara or Muyalaka[4]) who symbolizes spiritual ignorance.[14][16]

The classical form of the depiction appears in a pillar of rock cut temple at Seeyamangalam –

Etymology

The word Nataraja is a Sanskrit term, from नट Nata meaning "act, drama, dance" and राज Raja meaning "king, lord"; it can be roughly translated as Lord of the dance or King of the dance.[22][23] According to Ananda Coomaraswamy, the name is related to Shiva's fame as the "Lord of Dancers" or "King of Actors".[24]

The form is known as Nataraja in Tamil Nadu and as Narteśvara (also written Nateshwar[25]) or Nṛityeśvara in North India, with all three terms meaning "Lord of the dance".[26] Narteśvara stems from Nṛtta same as Nata which means "act, drama, dance" and Ishvara meaning "lord".[27] Natesa (IAST: Naṭeśa) is another alternate equivalent term for Nataraja found in 1st-millennium sculptures and archeological sites across the Indian subcontinent.[28]

In Tamil, he is also known as “Sabesan” (Tamil: சபேசன்) which splits as “Sabayil adum eesan” (Tamil: சபையில் ஆடும் ஈசன்) which means “The Lord who dances on the dais”. This form is present in most Shiva temples, and is the prime deity in the Nataraja Temple at Chidambaram (Tillai).[29] The dance of Shiva in Chidambaram forms the motif for all the depictions of Shiva as Nataraja. Koothan(ta: கூத்தன், romanized: Kūththaṉ), Sabesan(ta: சபேசன், romanized: Sabēsaṉ), Ambalavanan (ta: அம்பலவாணன், romanized: Ambalavāṇaṉ) are other common names of Nataraja in Tamil texts.[30][31]

Depiction

The sculpture is symbolic of Shiva as the lord of dance and dramatic arts,[13] with its style and proportions made according to Hindu texts on arts.[14] The two most common forms of Shiva's dance are the Lasya (the gentle form of dance), associated with the creation of the world, and the Ananda Tandava (dance of bliss, the vigorous form of dance), associated with the destruction of weary worldviews—weary perspectives and lifestyles. In essence, the Lasya and the Tandava are just two aspects of Shiva’s nature; for he destroys in order to create, tearing down to build again.[32]

According to Alice Boner, the historic Nataraja artworks found in different parts of India are set in geometric patterns and along symmetric lines, particularly the satkona mandala (hexagram) that in the Indian tradition means the interdependence and fusion of masculine and feminine principles.[33]

It typically shows Shiva dancing in one of the Natya Shastra poses, holding Agni (fire) in his left back hand, the front hand in gajahasta (elephant hand) or dandahasta (stick hand) mudra, the front right hand with a wrapped snake that is in abhaya (fear not) mudra while pointing to a Sutra text, and the back hand holding a musical instrument, usually a Udukai (Tamil: உடுக்கை).[14] His body, fingers, ankles, neck, face, head, ear lobes and dress are shown decorated with symbolic items, which vary with historic period and region.[3][15] He is surrounded by a ring of flames, standing on a lotus pedestal, lifting his left leg (or in rare cases, the right leg) and balancing / trampling upon a demon shown as a dwarf (Apasmara or Muyalaka[4]) who symbolizes spiritual ignorance.[14][16] The dynamism of the energetic dance is depicted with the whirling hair which spread out in thin strands as a fan behind his head.[34][35] The details in the Nataraja artwork have been variously interpreted by Indian scholars since the 12th century for its symbolic meaning and theological essence.[19][24] Nataraja is a well known sculptural symbol in India and popularly used as a symbol of Indian culture,[6][7] in particular as one of the finest illustrations of Hindu art.[8][9]

Symbolism

The dance of Nataraja is revealed in a story mentioned in the Koyil Puranam.

- He dances within a circular or cyclically closed arch of flames (prabha mandala), which symbolically represent the cosmic fire that in Hindu cosmology creates everything and consumes everything, in cyclic existence or cycle of life. The fire also represents the evils, dangers, heat, warmth, light and joys of daily life. The arch of fire emerges from two makara(mythical water beasts) on each end.

- He looks calm, even through the continuous chain of creation and destruction that maintains the universe, that shows the supreme tranquility of the Atma.[37]

- His legs are bent, which suggests an energetic dance. His long, matted tresses, are shown to be loose and flying out in thin strands during the dance, spread into a fan behind his head, because of the wildness and ecstasy of the dance.

- On his right side, meshed in with one of the flying strands of his hair near his forehead, is typically the river Ganges personified as a goddess, from the Hindu mythology where the danger of a mighty river is creatively tied to a calm river for the regeneration of life.

- His headdress often features a human skull (symbol of mortality), a crescent moon and a flower identified as that of the entheogenic plant Datura metel.

- Four-armed figures are most typical, but ten-armed forms are also found from various places and periods, for example the Ankor Wat.

- The upper right hand holds a small drum shaped like an hourglass that is called a It symbolizes rhythm of creation and time.

- The upper left hand contains Agni or fire, which signifies destruction.

- A cobra uncoils from his lower right forearm, while his hand is in the abhaya mudra gesture as a sign to not fear

- The lower left hand is bent downwards at the wrist with the palm facing inward, we also note that this arm crosses Naṭarāja’s chest, concealing his heart from view. It represents tirodhāna, which means “occlusion, concealment.”

- The face shows two eyes plus a slightly open third on the forehead, which symbolize the triune in Shaivism. The eyes represent the sun, the moon and the third has been interpreted as the inner eye, or symbol of knowledge (jnana), urging the viewer to seek the inner wisdom, self-realization. The three eyes alternatively symbolize an equilibrium of the three Guṇas: Sattva, Rajas and Tamas.

- The dwarf underneath his foot is the demon Apasmara purusha or Muyalaka, who symbolizes ignorance which Nataraja destroys.

- The slightly smiling face of Shiva represents his calmness despite being immersed in the contrasting forces of universe and his energetic dance.[19]

Padma Kaimal questions some of these interpretations by referring to a 10th-century text and Nataraja icons, suggesting that the Nataraja statue may have symbolized different things to different people or in different contexts, such as Shiva being the lord of cremation or as an emblem of Chola dynasty.

Interpretation

Coomaraswamy summarizes the significance of Shiva's entire dance as an image of his rhythmic or musical play which is the source of all movement within the universe, represented by the arch surrounding Shiva. Secondly, the purpose of his dance is to release the souls of all men from illusion. And third, the place of the dance, Chidambaram, which is portrayed as the center of the universe, is actually within the heart.[29]

James Lochtefeld states that Nataraja symbolizes "the connection between religion and the arts", and it represents Shiva as the lord of dance, encompassing all "creation, destruction and all things in between".

In the hymn of

Srinivasan notes that Nataraja is described as

According to Ian Crawford, professor of planetary science at University of London, the cosmic dance of Shiva as Nataraja represents particle physics, entropy and the dissolution of the universe.[48]

History

Stone reliefs depicting the classical form of Nataraja are found in numerous cave temples of India, such as at the

Literary evidences shows that the bronze representation of Shiva's ananda-tandava appeared first in the Pallava period between 7th century and mid-9th centuries CE.[50] Nataraja was worshipped at Chidambaram during the Pallava period with underlying philosophical concepts of cosmic cycles of creation and destruction, which is also found in Tamil saint Manikkavacakar's Thiruvasagam.[51]

Archaeological discoveries have yielded a red Nataraja sandstone statue, from 9th to 10th century from Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh, now held at the Gwalior Archaeological Museum.[52][53] Similarly, Nataraja artwork has been found in archaeological sites in the Himalayan region such as Kashmir, albeit in with somewhat different dance pose and iconography, such as just two arms or with eight arms.[54]

Around the 10th century, it emerged in

The depiction was informed of cosmic or

In medieval era artworks and texts on dancing Shiva found in

In the contemporary Hindu culture of Bali in Indonesia, Siwa (Shiva) Nataraja is the god who created dance.[59] Siwa and his dance as Nataraja was also celebrated in the art of Java Indonesia when Hinduism thrived there, while in Cambodia he was referred to as Nrittesvara.[60]

In 2004, a 2 meter statue of the dancing Shiva was unveiled at CERN, the European Center for Research in Particle Physics in Geneva. The statue, symbolizing Shiva's cosmic dance of creation and destruction, was given to CERN by the Indian government to celebrate the research center's long association with India.[61] A special plaque next to the Shiva statue explains the metaphor of Shiva's cosmic dance with quotations from physicist Fritjof Capra:

Hundreds of years ago, Indian artists created visual images of dancing Shivas in a beautiful series of bronzes. In our time, physicists have used the most advanced technology to portray the patterns of the cosmic dance. The metaphor of the cosmic dance thus unifies ancient mythology, religious art and modern physics.[62]

Though named "Nataraja bronzes" in Western literature, the Chola Nataraja artworks are mostly in copper, and a few are in brass, typically cast by the cire-perdue (lost-wax casting) process.[34]

Nataraja is celebrated in 108 poses of Bharatanatyam, with Sanskrit inscriptions from Natya Shastra, at the Nataraja temple in Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu, India.[3][5]

In dance and yoga

In modern yoga as exercise, Natarajasana is a posture resembling Nataraja and named for him in the 20th century.[63] A similar pose appears in the classical Indian dance form Bharatanatyam.[64]

-

Nataraja pose in Bharatanatyam classical Indian dance

-

Natarajasana in modern yoga as exercise

Gallery

-

Asanpata Nataraja with Naga King Satrubhanja (261AD) Inscription at Keonjhar district of Odisha 3rd Century AD

-

A damaged 6th-century Nataraja, Elephanta Caves[65]

-

6th-century Nataraja in Cave 21, Ellora Caves[17]

-

8th-century Nataraja inKailasa temple(Cave 16), Ellora Caves

-

Ithyphallic8th-century sandstone Nataraja from Madhya Pradesh

-

Sukanasa with Shiva Nataraja in Pattadakal, Karnataka

-

The oldest known Tamil bronze Nataraja, 800 AD, British Museum[66]

-

Khmer relief, 12th-century, Angkor Wat

-

Shiva-Nataraja in the Thousand-Pillar-Hall of Meenakshi Temple in Madurai, Tamil Nadu

-

In the Shiva temple of Melakadambur is a rare Pala image that shows the ten-armed Nataraja dancing on his bull, Nandi

References

- ^ "கூத்தன் சபேசன் அம்பலவாணன் நடராஜன்Sagarva Bharath Foundation". Sagarva Bharath Foundation. 20 July 2020.

- ^ Rajarajan, R. K. K. (January 2018). "If this is Citambaram-Nataraja, then where is Tillai-Kūttaṉ? An Introspective Reading of Tēvāram Hymns". In Pedarapu Chenna Reddy, ed. History, Culture and Archaeological Studies Recent Trends, Commemoration Volume to Prof. M.L.K. Murthy, Vol. II, Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corporation, Pp. 613-634, PLS. 54.1-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4438-2832-1.

- ^ a b c Encyclopædia Britannica (2015)

- ^ ISBN 978-81-208-0877-5.

- ^ a b c Gomathi Narayanan (1986), SHIVA NATARAJA AS A SYMBOL OF PARADOX, Journal of South Asian Literature, Vol. 21, No. 2, pages 208-216

- ^ ISBN 978-0-674-02691-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-52865-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-517667-4.

- ^ ValaiTamil. "அம்பலவாணன், Ambalavanan, Boy Baby Name (Tamil Name), complete collection of boy baby name, girl baby name, tamil name". ValaiTamil. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "General Compendium-5 - GKToday". www.gktoday.in. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "The Lord (or King) of Dance". www.speakingtree.in. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-81-7099-016-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-81-208-0877-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-81-208-0877-5.

- ^ The Art Institute of Chicago, United States

- ^ ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4094-3029-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5.

- ^ JSTOR 3249451.

- ^ ISBN 978-81-208-0053-3.

- ISBN 978-8129120908.

- ^ Stromer, Richard. "Shiva Nataraja: A Study in Myth, Iconography, and the Meaning of a Sacred Symbol" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d The Dance of Shiva, Ananda Coomaraswamy

- ^ "A journey to the past with dancing Shiva". The Daily Star. 27 September 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

in an Old Dhaka temple ... a stone statue of Nateshwar, a depiction of dancing Shiva on the back of his bull-carrier Nandi

- ISBN 978-0520064775.

- ISBN 978-2-85539-666-8.

- ISBN 0-87633-039-1.

- ^ a b c Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish (1918). The dance of Siva; fourteen Indian essays. Robarts - University of Toronto. New York Sunwise Turn. pp. 57–58, 65.

- ^ "கூத்தன் சபேசன் அம்பலவாணன் நடராஜன்SAGARVA BHARATH FOUNDATION". SAGARVA BHARATH FOUNDATION. 20 July 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ ":: TVU ::". www.tamilvu.org. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ISBN 0691040095

- ISBN 978-81-208-0705-1.

- ^ Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin, Vol. 20, No. 118 (Apr., 1922), pages 18-19

- ^ Gomathi Narayanan (1986), SHIVA NATARAJA AS A SYMBOL OF PARADOX, Journal of South Asian Literature, Vol. 21, No. 2, page 215

- ^ Shiva Nataraja, lord of the dance Encyclopedia of Ancient History (2013)

- ^ a b DeVito, Carole; DeVito, Pasquale (1994). India - Mahabharata. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminar Abroad 1994 (India). United States Educational Foundation in India. p. 5.

- ^ Alice Boner; Sadāśiva Rath Śarmā (1966). Silpa Prakasa Medieval Orissan Sanskrit Text on Temple Architecture. Brill Archive. pp. xxxvi, 144.

- ^ For the damaru drum as one of the attributes of Shiva in his dancing representation see: Jansen, page 44.

- ^ Jansen, page 25.

- ^ Padma Kaimal (1999), Shiva Nataraja: Shifting Meanings of an Icon, The Art Bulletin Volume 81, Issue 3, pages 390-419

- ^ Srinivasan 2004, pp. 432–450.

- ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- ISBN 978-0-521-52865-8.

- ISBN 978-0-275-22950-4.

- ^ Srinivasan 2004, pp. 447.

- .

- ^ Rupendra Chattopadhya et al (2013), The Kingdom of the Saivacaryas, Berlin Indological Studies, volume 21, page 200; Archive

- ^ ISBN 9788131711200.

- ^ Srinivasan 2004, pp. 444–445.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5.

- ISBN 9780195613544.

- ISBN 978-0-19-537852-8.

- ^ Sharada Srinivasan, "Shiva as 'cosmic dancer': on Pallava origins for the Nataraja bronze", World Archaeology (2004) 36(3), pages 432–450.

- ISBN 9780195613544.

- ISBN 9780195613544.

- ISBN 978-967-65-3071-4.

- ISBN 978-974-8434-12-4.

- ^ "Faces and Places (page 3)". CERN Courier. Archived from the original on 6 June 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ "Shiva's Cosmic Dance at CERN | Fritjof Capra". fritjofcapra.net. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ISBN 978-1855381667.

- ^ Bhavanani, Ananda Balayogi; Bhavanani, Devasena (2001). "BHARATANATYAM AND YOGA". Archived from the original on 23 October 2006. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

He also points out that these [Bharatanatyam dance] stances are very similar to Yoga Asanas, and in the Gopuram walls at Chidambaram, at least twenty different classical Yoga Asanas are depicted by the dancers, including Dhanurasana, Chakrasana, Vrikshasana, Natarajasana, Trivikramasana, Ananda Tandavasana, Padmasana, Siddhasana, Kaka Asana, Vrishchikasana and others.

- ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5.

- ^ British Museum Collection

Further reading

- Ananda Coomaraswamy (1957). The Dance of Śiva: Fourteen Indian Essays. Sunwise Turn. OCLC 2155403.

- Jansen, Eva Rudy (1993). The Book of Hindu Imagery. Havelte, Holland: Binkey Kok Publications BV. ISBN 90-74597-07-6.

- Vivek Nanda; George Michell (2004). Chidambaram: Home of Nataraja. Marg Publications. OCLC 56598256.

- C Sivaramamurti (1974). Nataraja in Art, Thought, and Literature. National Museum. OCLC 1501803.

- David Smith (2003). The Dance of Siva: Religion, Art and Poetry in South India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52865-8.

- Srinivasan, Sharada (2004). "Shiva as 'cosmic dancer': On Pallava origins for the Nataraja bronze". World Archaeology. Vol. 36. The Journal of Modern Craft. pp. 432–450. S2CID 26503807.

External links

- Śiva's Dance: Iconography and Dance Practice in South and Southeast Asia, Alessandra Iyer (2000), Music in Art

- Shiva Nataraja Iconography, Freer Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian

- Nataraja: India's Cycle of Fire, Stephen Pyne (1994)

- Chidambareswarar Nataraja Temple

- Nataraja Image Archive

![A damaged 6th-century Nataraja, Elephanta Caves[65]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8a/Elephanta_Island.jpg/202px-Elephanta_Island.jpg)

![6th-century Nataraja in Cave 21, Ellora Caves[17]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ca/1_Dancing_Shiva%2C_Cave_21_at_Ellora.jpg/276px-1_Dancing_Shiva%2C_Cave_21_at_Ellora.jpg)

![The oldest known Tamil bronze Nataraja, 800 AD, British Museum[66]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/98/Shiva_Nataraja_%28BM%29.JPG/216px-Shiva_Nataraja_%28BM%29.JPG)