National Archaeological Museum (Madrid)

Museo Arqueológico Nacional | |

| |

| |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Established | March 20, 1867 |

|---|---|

| Location | Calle de Serrano, 13, Madrid, Spain |

| Coordinates | 40°25′25.122″N 3°41′21.919″W / 40.42364500°N 3.68942194°W |

| Type | Archaeology museum |

| Visitors | 499,300 (2019)[1] |

| Director | Andrés Carretero Pérez |

| Website | man |

| Official name | Museo Arqueológico Nacional |

| Type | Non-movable |

| Criteria | Monument |

| Designated | 1962 |

| Reference no. | RI-51-0001373 |

The National Archaeological Museum (

History

The museum was founded in 1867 by a Royal Decree of

The museum was originally located in the

Following a restructuring of the collection in the 1940s, its former pieces relative to the section of American Ethnography were transferred to the

Its current collection is based on pieces from the Iberian Peninsula, from Prehistory to Early-Modern Age. However, it also has different collections coming from outside of Spain, especially from Ancient Greece, both from the metropolitan and, above all, from Magna Graecia, and, to a lesser extent, from Ancient Egypt, in addition to "a small number of pieces" from Near East.[5]

Permanent exhibition

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2020) |

Forecourt

In the forecourt is a replica of the Cave of Altamira from the 1960s. Photogrammetry was used to reproduce the famous paintings on a mould of the original cave. The replica cave is related to an exhibit at the Deutsches Museum in Munich.[6]

Main building

Visitors enter the building at basement level, and pass to the prehistory section.

Protohistory

The halls devoted to the Protohistory of the Iberian Peninsula (1st floor) exhibit pieces from

-

Iberian mausoleum of Pozo Moro.

Aside from the set of Iberian sculpture, the area also hosts other items from different cultures, such as the Talaiotic bulls of Costitx, the torque of Ribadeo from the Castro culture in northwestern Iberia, or the Lady of Ibiza, associated to the Punic civilization.[7]

-

Bull heads of Costitx

-

Torque of Ribadeo

-

Punic Lady of Ibiza

-

Wheel of Toya

-

The Priest of Cadiz.

Roman Hispania

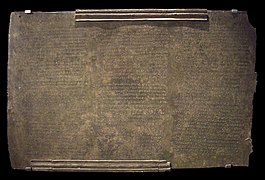

The collection of Hispano-Roman artifacts—located in the 1st floor—comes both from diggings at specific archaeological sites as well as from punctual purchases.

-

Mosaic of Winter, from Quintana del Marco

-

One the slabs part of the Lex Ursonensis

-

Mosaic of Medusa and the seasons from Palencia

-

Hypnos from Algorós

Late Antiquity

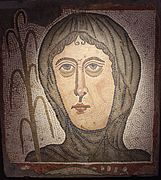

The halls corresponding to the

Standout artifacts from this area include the Sarcophagus from Astorga, the Visigothic hoard of Guarrazar, including the votive crown of Recceswinth,[16] or the fibulae from Alovera.[15]

-

Paleochristian sarcophagus from Astorga

-

Votive crown of Recceswinth

Medieval World, al-Andalus

The area dedicated to

-

The deer of Medina Azahara, a bronze fountain

-

Ablution font of Medina Alzahira

-

One of the Alhambra vases

Medieval World, Christian kingdoms

The area dedicated to the medieval Christian Kingdoms (roughly ranging from the 8th to the 15th century) is located in the 2nd floor. Iconic pieces of Romanesque ivory craftsmanship include the Arca de las Bienaventuranzas and the Crucifix of Ferdinand and Sancha.[21] The medieval collection features the praying statue of Peter I of Castile, made in alabaster and moved from the former convent of Santo Domingo el Real in Madrid to the National Archaeological Museum in 1868.[22][21] It also displays a number of items of Levantine pottery.[21]

-

Pottery from Manises

Near East

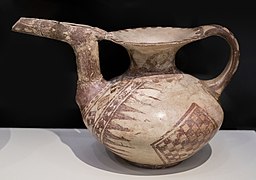

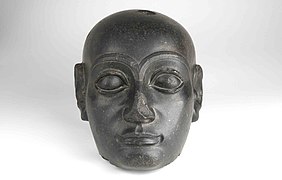

The topic area devoted to the

-

Pottery from Tepe Sialk

-

Brick fromcuneiform writing

-

Praying Sumerian figure

-

Head of Gudea (Lagash period)

Egypt and Nubia

The collections of Egypt and Nubia are made up mainly of funerary funds (amulets, mummies, steles, sculpture of divinities, ushabti...) ranging from prehistory to Roman and medieval times.[26] Many of the pieces come from purchases such as the one made from the collection of the Spanish Egyptologist Eduardo Toda y Güell[27] and also from various excavations such as the ones carried in Egypt and Sudan as a result of the agreements with the Egyptian government for the construction of the Aswan Dam[28] or the systematic excavations in Heracleopolis Magna.

-

Stele of Nebsumenu from the Second Intermediate Period (1650–1550 BC)

-

Basalt sculpture of Harsomtus em hat from the twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt.

-

Late period sarcophagus.

-

Cocodrile baby mummy.

-

Black basalt sculpture of horus.

-

Ptolemaic period sculpture.

Greece

The Greek collection is made up of works from continental Greece, Ionia, Magna Graecia and Sicily, where the collection of bronzes, terracottas, goldsmiths, sculptures and to a greater extent pottery come from; pieces that ranging from the Mycenaean to the Hellenistic period.[29] In its beginnings, the collection had funds from the Royal Cabinet of Natural History and the National Library, the collection was later enriched with works brought from the expeditions of the frigate Arapiles to the East[28] in addition to the purchase of private funds such as those of the Marquis of Salamanca[30] or those of Tomás Asensi.

-

Archaic period hoplite armor set.

-

Crater of the Madness of Herakles.

-

Dog-headed rhyton.

-

Roman copy of a Lyssippus original.

Notable artifacts

- Prehistoric and Iberian

- Lady of Elche

- Lady of Baza

- Lady of Galera

- Dama del Cerro de los Santos

- Biche of Balazote

- Bull of Osuna

- Magacela stele

- Mausoleum of Pozo Moro

- Sphinx of Agost

- Roman

- Medieval

- Pyxis of Zamora

- One of the Alhambra vases

See also

References

- ^ culturaydeporte.gob.es

- ^ Lanzarote Guiral, José María (2011). "National Museums in Spain: A History of Crown, Church and People". In Aronsson, Peter; Elgenius, Gabriella (eds.). Building National Museums in Europe 1750–2010 (PDF). Linköping University Electronic Press. p. 853.

- ^ Official website (in Spanish), plus information from Madrid Tourist Office etc, as at November 24, 2013.

- ISSN 0212-5544.

- ^ "Egipto y Oriente Próximo", Museo Arqueológico Nacional (in Spanish)

- ^ "The Deutsches Museum Replica". Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- ^ a b "Protohistoria" (PDF). pp. 34–51.

- ABC.

- ^ Prieto, Ignacio M. (2009). "Esfinge de El Salobral" (PDF).

- ^ ISBN 978-84-472-1071-8.

- ^ a b Salas Álvarez 2015, p. 281.

- ISSN 1139-9201.

- ^ Salas Álvarez 2015, p. 283.

- ISSN 2341-3409.

- ^ a b "De la Antigüedad a la Edad Media" (PDF). Museo Arqueológico Nacional.

- ^ a b Franco Mata, Ángela; Balmaseda Muncharaz, Luis; Arias Sánchez, Isabel; Vidal Álvarez, Sergio. "Nuevo montaje de la colección de Arqueología y Arte Medieval del Museo Arqueológico Nacional" (PDF). pp. 422–425.

- ISSN 1139-9201.

- ^ "El mundo medieval. Al-Andalus" (PDF). p. 78.

- ISSN 0214-6452.

- ^ Martín Moreno, Elena (November 2016). "La transmisión del saber clásico Astrolabio andalusí de Ibn Said" (PDF).

- ^ a b c "Los reinos cristianos (s. VIII–XV)" (PDF). pp. 82, 85.

- ^ Cómez Ramos, Rafael (2006). "Iconología de Pedro I de Castilla" (PDF). Historia. Instituciones. Documentos. 33. Seville: Universidad de Sevilla: 68–69.

- ^ "Oriente Próximo Antiguo" (PDF). p. 109.

- ISSN 1885-5008.

- ^ "Museo arqueológico Nacional. Memoria anual 2001" (PDF). p. 12.

- ^ "Egypt and the Near East". www.man.es. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- ^ Mellado, Esther Pons (2018). "La colección egipcia de Eduard Toda i Güell del Museo Arqueológico Nacional". Arqueología de los museos. 150 años de la creación del Museo Arqueológico Nacional: Actas del V Congreso Internacional de Historia de la Arqueología / IV Jornadas de Historia SEHA - MAN, 2018, págs. 1075-1090. Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones: 1075–1090.

- ^ a b "Museum collections". www.man.es. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- ^ "Greece". www.man.es. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- ^ "Publications - Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport". sede.educacion.gob.es. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

External links

- National Archaeological Museum of Spain - Muselia

- Official list of museums in Spain

- National Archaeological Museum (Madrid) within Google Arts & Culture

Media related to Museo Arqueológico Nacional de España at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Museo Arqueológico Nacional de España at Wikimedia Commons

![Lioness of Baena [es]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/94/Leona_de_Baena_%2840730657161%29.jpg/292px-Leona_de_Baena_%2840730657161%29.jpg)

![Sundial from Baelo Claudia [es]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/12/Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional_-_33185_-_Reloj_solar_de_Baelo_Claudia.jpg/148px-Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional_-_33185_-_Reloj_solar_de_Baelo_Claudia.jpg)

![Puteal from La Moncloa [es]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional_-_2691_-_Puteal_de_la_Moncloa_03.jpg/127px-Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional_-_2691_-_Puteal_de_la_Moncloa_03.jpg)

![Paleochristian sarcophagus from Astorga [es]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional_-_50310_-_Sarc%C3%B3fago_de_Astorga.jpg/306px-Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional_-_50310_-_Sarc%C3%B3fago_de_Astorga.jpg)

![Eagle-like fibulae from Alovera [es]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/da/Alovera_M.A.N..JPG/264px-Alovera_M.A.N..JPG)

![The deer of Medina Azahara [es], a bronze fountain](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3a/Cierva_%2840707126722%29.jpg/170px-Cierva_%2840707126722%29.jpg)

![Astrolabe of ibn Said [es], made in 1067 in Toledo by Ibrahim ibn Said al-Sahli[20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ad/Astrolabio_%2816787706916%29.jpg/168px-Astrolabio_%2816787706916%29.jpg)

![Arca de las Bienaventuranzas [es]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d0/ArquetaDeLasBienaventuranzas.jpg/187px-ArquetaDeLasBienaventuranzas.jpg)

![praying statue of Peter I of Castile [es]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/M.A.N._-_Estatua_orante_de_Pedro_I.jpg/91px-M.A.N._-_Estatua_orante_de_Pedro_I.jpg)