Naval history of China

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

The naval history of China dates back thousands of years, with archives existing since the late Spring and Autumn period regarding the Chinese navy and the various ship types employed in wars.[1] The Ming dynasty of China was the leading global maritime power between 1400 and 1433, when Chinese shipbuilders built massive ocean-going junks and the Chinese imperial court launched seven maritime voyages.[2] In modern times, the current People's Republic of China and the Republic of China governments continue to maintain standing navies through the People's Liberation Army Navy and the Republic of China Navy, respectively.

History

Early coastal maritime endeavours

The

Although naval battles took place before the 12th century, such as the large-scale

When the British

A significant naval battle was the

Ming expeditions and decline

After the period of maritime activity during the

Despite Ming ambivalence towards naval affairs, the

However, the Chinese fleet shrank tremendously after its military/tributary/exploratory functions in the early 15th century were deemed too expensive and it became primarily a police force on routes like the

In 1521, at the

The continuing "sea ban" policy during the early Qing dynasty meant that the development of naval power stagnated. River and coastal naval defence was the responsibility of the waterborne units of the Green Standard Army, which were based at Jingkou (now Zhenjiang) and Hangzhou.

In 1661, a naval unit was established at

In the 1860s, an attempt to establish a modern navy via the British-built Osborn or "Vampire" Fleet to combat the Taiping rebels' US-built gunboats. The so-called "Vampire Fleet" fitted out by the Chinese government for the suppression of piracy on the coast of China, owing to the non-fulfilment of the condition that British commander Sherard Osborn should receive orders from the imperial government only, was scrapped.[12]

There were four fleets of the Imperial Chinese Navy:

- Weihaiwei

- Nanyang Fleet - South Sea Fleet based from Shanghai

- Guangdong Fleet - based from Canton (now Guangzhou)

- Fujian Fleet - based from Fuzhou, founded in 1678 as the Fujian Marine Fleet [13]

In 1865, the Jiangnan Shipyard was established.

In 1874, a Japanese incursion into Taiwan exposed the vulnerability of China at sea. A proposal was made to establish three modern coastal fleets: the Northern Sea or Beiyang Fleet, to defend the Yellow Sea, the Southern Sea or Nanyang Fleet, to defend the East China Sea, and the Canton Sea or Yueyang Fleet, to defend the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea. The Beiyang Fleet, with a remit to defend the section of coastline closest to the capital Beijing, was prioritised.

A series of warships were ordered from Britain and Germany in the late 1870s, and naval bases were built at

The Nanyang Fleet was also established in 1875, and grew with mostly domestically built warships and a small number of acquisitions from Britain and Germany. It fought in the Sino-French War, performing somewhat poorly against the French in all engagements and resulting in allowing the French colonization of Southeast Asia. The defeat of the Nanyang Fleet also emboldened the British to complete their annexation of Burma in the Third Anglo-Burmese War.[citation needed]

The separate

After the First Sino-Japanese War, Zhang Zhidong established a river-based fleet in Hubei.

In 1909, the remnants of the Beiyang, Nanyang, Guangdong and Fujian Fleets, together with the Hubei fleet, were merged, and re-organised as the Sea Fleet and the River Fleet.

In 1911, Sa Zhenbing became the Minister of Navy of the Great Qing.

One of the new ships delivered after the war with Japan, the cruiser Hai Chi, in 1911 became the first vessel flying the Yellow Dragon Flag to arrive in American waters, visiting New York City as part of a tour.[15][16][17][18]

Modern

The

The

Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, the

In 2020 the PLAN surpassed the U.S. Navy as the largest navy in the world in numbers of ships, although the U.S. Navy continued to have technological advantages. This development occurred amid increasing tensions between China and the United States and as China was becoming involved in territorial disputes in the South China Sea.[22]

Literature

Early literature

One of the oldest known Chinese books written on naval matters was the Yuejueshu (Lost Records of the State of Yue) of 52 AD, attributed to the Han dynasty scholar Yuan Kang.[1] Many passages of Yuan Kang's book were rewritten and published in Li Fang's Imperial Reader of the Taiping Era, compiled in AD 983.[23] The preserved written passages of Yuan Kang's book were again featured in the Yuanjian Leihan (Mirror of the Infinite, a Classified Treasure Chest) encyclopedia, edited and compiled by Zhang Ying in 1701 during the Qing dynasty.[1]

Yuan Kang's book listed various water crafts that were used for war, including one that was used primarily for

Nowadays in training naval forces we use the tactics of land forces for the best effect. Thus great wing ships correspond to the army's heavy chariots, little wing ships to light chariots, stomach strikers to battering rams, castle ships to mobile assault towers, and bridge ships to light cavalry.[1]

Ramming vessels were also attested to in other Chinese documents, including the Shi Ming dictionary of c. 100 AD written by Liu Xi.[25] The Chinese also used a large iron t-shaped hook connected to a spar to pin retreating ships down, as described in the Mozi book compiled in the 4th century BC.[26] This was discussed in a dialogue between Mozi and Lu Ban in 445 BC (when Lu traveled to the State of Chu from the State of Lu), as the hook-and-spar technique made standard on all Chu warships was given as the reason why the Yue navy lost in battle to Chu.[27]

The rebellion of

The 'castle ship' design described by Yuan Kang saw continued use in Chinese naval battles after the Han period. Confronting the navy of the Chen dynasty on the Yangtze River, Emperor Wen of Sui (r. 581–604) employed an enormous naval force of thousands of ships and 518,000 soldiers stationed along the Yangtze (from Sichuan to the Pacific Ocean).[29] The largest of these ships had five layered decks, could hold 800 passengers, and each ship was fitted with six 50 ft. long booms that were used to swing and damage enemy ships, along with the ability of pinning them down.[29]

Vessels of the Tang dynasty

During the Chinese

Covered swoopers

starboard, there are openings for crossbows and holes for spears. Enemy parties cannot board (these ships), nor can arrows or stones injure them. This arrangement is not adopted for large vessels because higher speed and mobility are preferable, in order to be able to swoop suddenly on the unprepared enemy. Thus these (covered swoopers) are not fighting ships (in the ordinary sense).[32]

Combat junks

Combat junks (Zhan xian); combat junks have ramparts and half-ramparts above the side of the hull, with the oar-ports below. Five feet from the edge of the deck (to port and starboard) there is set a deckhouse with ramparts, having ramparts above it as well. This doubles the space available for fighting. There is no cover or roof over the top (of the ship). Serrated pennants are flown from staffs fixed at many places on board, and there are gongs and drums; thus these (combat junks) are (real) fighting ships (in the ordinary sense).[32]

Flying barques

Flying barques (Zou ge); another kind of fighting ship. They have a double row of ramparts on the deck, and they carry more sailors (lit. rowers) and fewer soldiers, but the latter are selected from the best and bravest. These ships rush back and forth (over the waves) as if flying, and can attack an enemy unawares. They are most useful for emergencies and urgent duty.[32]

Patrol boats

Patrol boats (Yu ting) are small vessels used for collecting intelligence. They have no ramparts above the hull, but to port and starboard there is one rowlock every four feet, varying in total number according to the size of the boat. Whether going forward, stopping, or returning, or making evolutions in formation, the speed (of these boats) is like flying. But they are for reconnaissance, they are not fighting boats/ships.[32]

Sea hawks

Sea hawks (Hai hu); these ships have low

overturn. Covering over and protecting the upper parts on both sides of the ship are stretched raw ox-hides, as if on a city wall [a footnote: protection against incendiary projectiles]. There are serrated pennants, and gongs and drums, just as on the fighting ships.[33]

Ships from the Wujing Zongyao

-

A "tower" ship with a traction-trebuchet on its top deck, from the Wujing Zongyao

-

A "combat" ship from the Wujing Zongyao

-

A "covered assault" ship from the Wujing Zongyao

-

A "flying" barque from the Wujing Zongyao

-

A "patrol" boat from the Wujing Zongyao

-

A "sea hawk" ship from the Wujing Zongyao

-

Chinese fire ships from the Wujing Zongyao

Spring and Autumn period

Warring States

Qin dynasty

Han dynasty

- 111 BCE, the delegates of Emperor Wu of Han explored Southeast Asia and India from the Gulf of Tonkin to make contact with central Asia states, the Silk Road of the Sea.

- Rebellion of Gongsun Shu

- Battle of Jiangxia

- Battle of Red Cliffs

- Battle of Ruxu (217)

Three Kingdoms

Sui dynasty

- Goguryeo-Sui Wars

Tang dynasty

Song dynasty

Yuan dynasty

Ming dynasty

- Battle of Lake Poyang

- Ming treasure voyages led by Zheng He

- Wokou

- Imjin War

- First Battle of Tamao

- Second Battle of Tamao

- Battle of Penghu (1624)

- Battle of Liaoluo Bay

- Siege of Fort Zeelandia

Qing dynasty

The Qing established a sea defence force of 7 fleets across 4 sea zones. Due to rebellions in the late 18th century the navy was neglected and declined, ultimately suffering defeat in the opium wars.

The modern

- Zheng Chengong

- Battle of Penghu

- Beiyang Fleet

- Nanyang Fleet

- Fujian Fleet

- Guangdong Fleet

- First and Second Opium Wars

- Sino-French War

- Battle of Foochow

- Battle of Shipu

- First Sino-Japanese War

- Battle of Yalu River (1894)

- Battle of Weihaiwei

Republic of China

- Republic of China Navy

- Second Sino-Japanese War

- Battle of Wuhan

- Landing Operation on Hainan Island

- First Taiwan Strait Crisis

- Second Taiwan Strait Crisis

- Third Taiwan Strait Crisis

People's Republic of China

- People's Liberation Army Navy

- First Taiwan Strait Crisis

- Second Taiwan Strait Crisis

- Battle of the Paracel Islands

- Third Taiwan Strait Crisis

- Spratly Island Skirmish (1988)

-

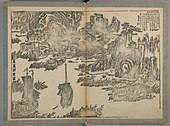

A restored copy of the illustration of Zheng He's visits to the West on the flyleaf of the book "Heavenly Princess Classics" in 1420. This invaluable picture is the earliest pictorial record of Zheng He treasure-ships.

-

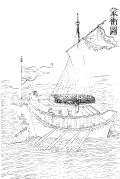

Sketch of Cheng Ho's ship

-

Ships of the world as depicted in the Fra Mauro map, 1460.

-

Ming dynasty war junk from Zheng Ruozeng's Chouhai tubian (1562)

-

River ships in Taiping Shanshui tu by Xiao Yuncong (1596-1673)

-

A two-masted Chinese junk, from the Tiangong Kaiwu of Song Yingxing, published in 1637

-

A Ming junk, 1637.

-

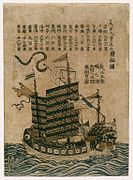

Early 17th-century Chinese woodblock print, thought to represent Zheng He's ships

-

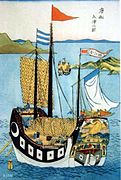

A Chinese junk in Japan, at the beginning of the Sakoku period (1644–1648 Japanese woodblock print)

-

Ming-Qing ship (Feng Zhou) from the Liuqiu guozhi lüe (The History of the Ryukyu Kingdom), 1759.

-

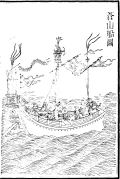

Barge,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

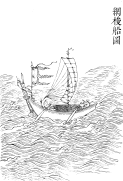

Covered swooper,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

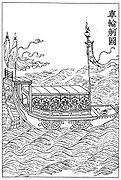

Walking barge,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Fighting ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Sea falcon ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Guangdong ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Xinhui sharp tail ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Dongguan great head ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Great fortune ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Grass ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Haicang ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Wave breaking ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

High branch ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Sound ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Leather bridge ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Cangshan ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Eight oar ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Falcon ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Fishing ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Netting ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

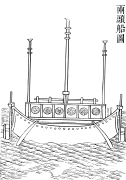

Two headed ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Sand ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Beak ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Son and mother boat,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Wheel barge,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Red dragon boat,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Fire ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Bomb laying boat,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Tower ship,Gujin Tushu Jicheng

-

Junk Keying travelled from China to the United States and England between 1846 and 1848.

-

Chinese ship, 1853.

-

Either the Chinese frigateHaian or Yuyuen, of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

Chinese gunboat Cedian, of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese ironclad Zhenyuan, of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese ironclad Dingyuan, of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiser Zhiyuan, of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiser Hai Chi, of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiser Hai Tien, of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiser Jingyuan (靖遠), of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiser Jingyuan (經遠), of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiser Laiyuan, of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiser Chaoyong, of the Imperial Chinese Navy.

-

The Chinese coastal defence shipZhongshan, of the Republic of China Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiser Chao Ho, of the Republic of China Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiser Ying Rui, of the Republic of China Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiser Ning Hai, of the Republic of China Navy.

-

The Chinese cruiser Ping Hai, of the Republic of China Navy.

-

A modern replica of the Chinese ironclad Dingyuan, as a museum ship.

-

Restored Chinese coastal defence ship Zhongshan, as a museum ship in the Zhongshan Warship Museum.

See also

- Military history of China before 1912

- Military history of China after 1911: PLA, ROCA

- History of canals in China

- technology of the Song dynasty

- Chinese exploration

- Imperial Chinese Navy

- Sailors in Ming China

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 678.

- ^ China in History — From 200 to 2005 Archived 2009-12-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 476.

- ^

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 31.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 463.

- ^ Graff, 86.

- ^ Sim 2017, p. 236.

- ^ Papelitzky 2017, p. 130.

- ^ Papelitzky 2017, p. 132.

- ^ Clowes, Sir William Laird (1903). "SHERARD OSBORN'S CHINESE FLEET". The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to the Death of Queen Victoria. Vol. 7. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. pp. 171–172.

- ISBN 9789004327214.

- ^ ISBN 9780870211928.

- Time magazine. July 17, 1933. Archived from the original on November 22, 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-18.("Pearl of the Sea") were still listed last week as the only cruisers in China's Northeastern Squadron.

The cruiser Hai Chi ("Flag of the Sea") earned in 1911 the distinction of being the first Chinese war boat ever to visit the West when she steamed as near as possible to the Coronation of King George V, discharged a cargo of Chinese emissaries in gorgeous silken robes. Built in 1897 the Hai Chi and the equally venerable Hai Shen

- New York Times. September 11, 1911. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

Who cruiser Hai-Chi of the Imperial Navy of China, the first vessel of any kind flying the yellow dragon flag of China that has ever been in American waters, steamed into the Hudson yesterday morning and anchored in midstream opposite the Soldiers and Sailors' Monument, at Eighty-ninth Street.

- Christian Science Monitor. September 12, 1911. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

Officers and men of the Chinese cruiser Hai-Chi, which arrived at this port Monday, are to be given ample opportunity to see New York during their stay of 10 days here. ...

- ^ New York Tribune September 12,1911

- ^ "歷史傳承 (History)". ROC Navy. Retrieved 2006-03-08. [dead link]

- ^ Pike, John. "People's Liberation Army Navy – History". Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "China has the world's largest navy — what now for the US? | DW | 21.10.2020". DW.COM. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 678, F.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 679.

- ^ a b c Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 680.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 681.

- ^ Needham, Volume 3, Part 4, 681-682.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 679-680.

- ^ a b Ebrey, 89.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 685-687.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 421–422.

- ^ a b c d Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 686.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 686-687.

- ISBN 1-86176-144-9. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

Sources

- Cole, Bernard D. (2010). The Great Wall at Sea: China's Navy in the Twenty-First Century (2nd ed.).

- Dewan, Sandeep (2012). China's Maritime Ambitions and the PLA Navy. Vij Books. ISBN 9789382573227.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006). East Asia: A Social, Cultural, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-13384-4.

- Fisher, Richard (2010). China's Military Modernization: Building for Regional and Global Reach. pp. excerpt and text search.

- Graff, David Andrew; Higham, Robin (2002). A Military History of China. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

- Lo, Jung-Pang (1955). "The Emergence of China as a Sea Power During the Late Sung and Early Yuan Periods". Far Eastern Quarterly. 4.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- ISBN 9780313293375.

- Yoshihara, Toshi; Holmes, James R., eds. (2010). Red Star over the Pacific: China's Rise and the Challenge to U.S. Maritime Strategy. p. excerpt and text search.

- Zheng, Yangwen (2011-10-14). China on the Sea: How the Maritime World Shaped Modern China. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-19477-9.

- Zurndorfer, Harriet (2016). "Oceans of history, seas of change: recent revisionist writing in western languages about China and East Asian maritime history during the period 1500–1630". S2CID 147906963.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. [1]

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. [1]