Necrotizing fasciitis

| Necrotizing fasciitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Flesh-eating bacteria, flesh-eating bacteria syndrome, handwashing[3] |

| Treatment | Surgery to remove the infected tissue, intravenous antibiotics[2][3] |

| Prognosis | ~30% mortality[2] |

| Frequency | 0.7 per 100,000 per year[4] |

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF), also known as flesh-eating disease, is a bacterial infection that results in the death of parts of the body's soft tissue.[3] It is a severe disease of sudden onset that spreads rapidly.[3] Symptoms usually include red or purple skin in the affected area, severe pain, fever, and vomiting.[3] The most commonly affected areas are the limbs and perineum.[2]

Typically, the infection enters the body through a break in the skin such as a cut or

Necrotizing fasciitis may be prevented with proper

Necrotizing fasciitis occurs in about 0.4 people per 100,000 per year in the U.S., and about 1 per 100,000 in Western Europe.[4] Both sexes are affected equally.[2] It becomes more common among older people and is rare in children.[4] It has been described at least since the time of Hippocrates.[2] The term "necrotizing fasciitis" first came into use in 1952.[4][7]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms may include fever, swelling, and complaints of excessive pain. The initial skin changes are similar to

However, those who are immunocompromised (have cancer, use

-

The very first symptom of NF. The center is clearly getting darker red (purple).

-

Early symptoms of necrotizing fasciitis. The darker red center is going black.

-

Necrotizing fasciitis type III caused by vibrio vulnificus.

Cause

Risk factors

More than 70% of cases are recorded in people with at least one of these clinical situations: immunosuppression, diabetes, alcoholism/drug abuse/smoking, malignancies, and chronic systemic diseases. For reasons that are unclear, it occasionally occurs in people with an apparently normal general condition.[9]

Necrotizing fasciitis can occur at any part of the body, but it is more commonly seen at the extremities,

The risk of developing necrotizing fasciitis from a wound can be reduced by good wound care and handwashing.[3]

Bacteria

Types of soft-tissue necrotizing infection can be divided into four classes according to the types of bacteria infecting the soft tissue. This classification system was first described by Giuliano and his colleagues in 1977.[4][2]

Type I infection: This is the most common type of infection, and accounts for 70 to 80% of cases. It is caused by a mixture of bacterial types, usually in abdominal or groin areas.

Clostridium sordellii can also produce two major toxins: all known virulent strains produce the essential virulence factor lethal toxin (TcsL), and a number also produce haemorrhagic toxin (TcsH). TcsL and TcsH are both members of the large clostridial cytotoxin (LCC) family.[10] The key Clostridium septicum virulence factor is a pore-forming toxin called alpha-toxin, though it is unrelated to the Clostridium perfringens alpha-toxin. Myonecrotic infections caused by these clostridial species commonly occur in injecting heroin users. Those with clostridial infections typically have severe pain at the wound site, where the wound typically drains foul-smelling blood mixed with serum (serosanguinous discharge). Shock can progress rapidly after initial injury or infection, and once the state of shock is established, the chance of dying exceeds 50%. Another bacterium associated with similar rapid disease progression is group A streptococcal infection (mostly Streptococcus pyogenes). Meanwhile, other bacterial infections require two or more days to become symptomatic.[2]

Type II infection: This infection accounts for 20 to 30% of cases, mainly involving the extremities.[4][11] This mainly involves Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria, alone or in combination with staphylococcal infections. Both types of bacteria can progress rapidly and manifest as toxic shock syndrome. Streptococcus species produce M protein, which acts as a superantigen, stimulating a massive systemic immune response which is not effective against the bacterial antigen, precipitating shock. Type II infection more commonly affects young, healthy adults with a history of injury.[2]

Type III infection: Vibrio vulnificus, a bacterium found in saltwater, is a rare cause of this infection, which occurs through a break in the skin. Disease progression is similar to type II but sometimes with little visible skin changes.[2]

Type IV infection: The type IV infection, which accounts for less than 1% of cases, is caused by the Candida albicans fungus. Risk factors include age and immunodeficiency.[4][12]

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis is difficult, as the disease often looks early on like a simple superficial skin infection.[4] While a number of laboratory and imaging modalities can raise the suspicion for necrotizing fasciitis, none can rule it out.[14] The gold standard for diagnosis is a surgical exploration in a setting of high suspicion. When in doubt, a small incision can be made into the affected tissue, and if a finger easily separates the tissue along the fascial plane, the diagnosis is confirmed and an extensive debridement should be performed.[2]

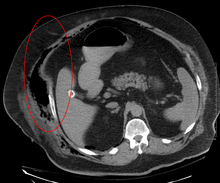

Medical imaging

Imaging has a limited role in the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. The time delay in performing imaging is a major concern. Plain radiography may show subcutaneous emphysema (gas in the

Scoring system

A white blood cell count greater than 15,000 cells/mm3 and serum sodium level less than 135 mmol/L have a sensitivity of 90% in detecting the necrotizing soft tissue infection.[citation needed] It also has a 99% chance of ruling out necrotizing changes if the values have shown otherwise. Various scoring systems are being developed to determine the likelihood of getting necrotizing fasciitis, but a scoring system developed by Wong and colleagues in 2004 is the most commonly used. It is the laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC) score, which can be used to stratify by risk those people having signs of severe cellulitis or abscess to determine the likelihood of necrotizing fasciitis being present. It uses six laboratory values: C-reactive protein, total white blood cell count, hemoglobin, sodium, creatinine, and blood glucose.[2] A score of 6 or more indicates that necrotizing fasciitis should be seriously considered.[16] The scoring criteria are:

- CRP (mg/L) ≥150: 4 points

- WBC count (×103/mm3)

- <15: 0 points

- 15–25: 1 point

- >25: 2 points

- Hemoglobin (g/dL)

- >13.5: 0 points

- 11–13.5: 1 point

- <11: 2 points

- Sodium (mmol/L) <135: 2 points

- Creatinine (umol/L) >141: 2 points

- Glucose (mmol/L) >10: 1 point[16][17]

However, the scoring system has not been validated. The values would be falsely positive if any other inflammatory conditions are present. Therefore, the values derived from this scoring system should be interpreted with caution.[2] About 10% of patients with necrotizing fasciitis in the original study still had a LRINEC score <6.[16] A validation study showed that patients with a LRINEC score ≥6 have a higher rate of both death and amputation.[18]

Prevention

Necrotizing fasciitis can be partly prevented by good

Treatment

Surgical debridement (cutting away affected tissue) is the mainstay of treatment for necrotizing fasciitis. Early medical treatment is often presumptive; thus, antibiotics should be started as soon as this condition is suspected. Tissue cultures (rather than wound swabs) are taken to determine appropriate antibiotic coverage, and antibiotics may be changed in light of results. Besides blood pressure control and hydration, support should be initiated for those with unstable vital signs and low urine output.[2]

Surgery

Aggressive wound debridement should be performed early, usually as soon as the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infection (NSTI) is made. Surgical incisions often extend beyond the areas of induration (the hardened tissue) to remove the damaged blood vessels that are responsible for the induration. However, cellulitic soft tissues are sometimes spared from debridement for later skin coverage of the wound. More than one operation may be used to remove additional necrotic tissue. In some cases when an extremity is affected by a NSTI, amputation may be the surgical treatment of choice. After the wound debridement, adequate dressings should be applied to prevent exposure of bones, tendons, and cartilage so that such structures do not dry out and to promote wound healing.[2]

For necrotizing infection of the perineal area (Fournier's gangrene), wound debridement and wound care in this area can be difficult because of the excretory products that often render this area dirty and affect the wound-healing process. Therefore, regular dressing changes with a fecal management system can help to keep the wound at the perineal area clean. Sometimes, colostomy may be necessary to divert the excretory products to keep the wound at the perineal area clean.[2]

-

Wound after aggressive acute debridement of NF

-

Necrotic tissue from the left leg surgically removed

-

Postsurgical debridement and skin grafting

-

After knee disarticulation amputation

Antibiotics

Empiric antibiotics are usually initiated as soon as the diagnosis of NSTI has been made, and then later changed to culture-guided antibiotic therapy. In the case of NSTIs, empiric antibiotics are broad-spectrum, covering gram-positive (including MRSA), gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria.[19]

While studies have compared moxifloxacin (a fluoroquinolone) and amoxicillin-clavulanate (a penicillin) and evaluated appropriate duration of treatment (varying from 7 to 21 days), no definitive conclusions on the efficacy of treatment, ideal duration of treatment, or the adverse effects could be made due to poor-quality evidence.[19]

Add-on therapy

- Hyperbaric oxygen: While human and animal studies have shown that high oxygen tension in tissues helps to reduce edema, stimulate fibroblast growth, increase the killing ability of white blood cells, inhibit bacterial toxin release, and increase antibiotic efficacy,[2] no high-quality trials have been shown to support or refute the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in patients with NSTIs.[19]

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG): No clear difference between using IVIG and placebo has been shown in the treatment of NSTIs, and one study showed serious adverse effects with IVIG use, including acute kidney injury, allergic reactions, aseptic meningitis syndrome, haemolytic anaemia, thrombi, and transmissible agents.[19]

- AB103: One study assessed the efficacy of a new type of treatment that affects the immune response, called AB103. The study showed no difference in mortality with use of this therapy, but it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions due to low-quality evidence.[19]

- Supportive therapy: Supportive therapy, often including intravenous hydration, wound care, anticoagulants to prevent thromboembolic events, pain control, etc. should always be provided to patients when appropriate.[citation needed]

Epidemiology

Necrotizing fasciitis affects about 0.4 in every 100,000 people per year in the United States.[4] About 1,000 cases of necrotizing fasciitis occur per year in the United States, but the rates have been increasing. This could be due to increasing awareness of this condition, leading to increased reporting, or bacterial virulence or increasing bacterial resistance against antibiotics.[2] In some areas of the world, it is as common as one in every 100,000 people.[4]

Higher rates of necrotizing fasciitis are seen in those with obesity or diabetes, and those who are immunocompromised or alcoholic, or have

History

In the fifth century BCE,

Society and culture

Notable cases

- 1994: Québec, Canada, who was infected while leader of the federal official opposition Bloc Québécois party, lost a leg to the illness.[22]

- 1994: A cluster of cases occurred in Gloucestershire, in the west of England. Of five confirmed and one probable infection, two died. The cases were believed to be connected. The first two had acquired the Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria during surgery; the remaining four were community-acquired.[23] The cases generated much newspaper coverage, with lurid headlines such as "Flesh Eating Bug Ate My Face".[24]

- 1997: Ken Kendrick, former agent and partial owner of the San Diego Padres and Arizona Diamondbacks, contracted the disease. He had seven surgeries in a little more than a week and later fully recovered.[25]

- 2004: Don Rickles, American stand-up comedian, actor, and author, known especially for his insult comedy, contracted the disease in his left leg. He had six operations and later recovered. The condition confined him in his later years to performing comedy from a chair.[26]

- 2004: Eric Allin Cornell, winner of the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics, lost his left arm and shoulder to the disease.[27]

- 2005: Alexandru Marin, an experimental particle physicist, professor at MIT, Boston University, and Harvard University, and researcher at CERN and JINR, died from the disease.[28]

- 2006 Alan Coren, British writer and satirist, announced in his Christmas column for The Times that his long absence as a columnist had been caused by his contracting the disease while on holiday in France.[29]

- 2009: R. W. Johnson, British journalist and historian, contracted the disease in March after injuring his foot while swimming. His leg was amputated above the knee.[30]

- 2011: Jeff Hanneman, guitarist for the thrash metal band Slayer, contracted the disease. He died of liver failure two years later, on May 2, 2013, and it was speculated that his infection was the cause of death. However, on May 9, 2013, the official cause of death was announced as alcohol-related cirrhosis. Hanneman and his family had apparently been unaware of the extent of the condition until shortly before his death.[31]

- 2011: Peter Watts, Canadian science fiction author, contracted the disease. On his blog, Watts reported, "I'm told I was a few hours away from being dead ... If there was ever a disease fit for a science-fiction writer, flesh-eating disease has got to be it. This ... spread across my leg as fast as a Star Trek space disease in time-lapse."[32]

- 2013: Georgie Henley, British actress. She revealed in 2022 that she had contracted the disease several weeks after starting at Cambridge University and that it had almost claimed her life.

- 2014: Daniel Gildenlöw, Swedish singer and songwriter for the band Pain of Salvation, spent several months in a hospital after being diagnosed with necrotizing fasciitis on his back in early 2014. After recovering, he wrote the album In the Passing Light of Day,[33] a concept album about his experience during the hospitalization.[34]

- 2014: Ricky Bartlett, CBS Radio Morning Host, had his left leg amputated. He got the disease during a trip to Wyoming & South Dakota, USA. He lost his right leg to bone disease (associated with the flesh eating disease he contacted) in 2022.[citation needed]

- 2015: Edgar Savisaar, Estonian politician, had his right leg amputated. He got the disease during a trip to Thailand.[35]

- 2018: Alex Smith, an American football quarterback for the Washington Football Team of the National Football League (NFL), contracted the disease after being injured during a game.[36] He suffered an open compound fracture in his lower leg, which became infected.[37] Smith narrowly avoided amputation, and eventually returned to playing professional football in October 2020.[38] Smith's injury and recovery is the subject of the ESPN documentary E60 Presents: Project 11.[39]

See also

- Capnocytophaga canimorsus

- Gangrene

- Mucormycosis, a rare fungal infection that can resemble necrotizing fasciitis (See type IV NF listing above)

- Noma (disease)

- Toxic shock syndrome

- Vibrio vulnificus

References

- ISBN 9780323313087. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ PMID 25069713.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Necrotizing Fasciitis: A Rare Disease, Especially for the Healthy". CDC. June 15, 2016. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ S2CID 9705500.

- ISBN 9780702070266.

- ISBN 978-0323084314.

- PMID 14915014.

- ^ a b c Trent, Jennifer T.; Kirsner, Robert S. (2002). "Necrotizing fasciitis". Wounds. 14 (8): 284–92.

- ISSN 2069-3850. Archived from the originalon 2016-03-22. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

- PMID 21199912.

- PMID 19228540.

- .

- ^ "UOTW#58 – Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 7 September 2015. Archived from the original on 18 July 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- PMID 30115465.

- PMID 19826154.

- ^ S2CID 15126133.

- ^ "LRINEC scoring system for necrotising fasciitis". EMT Emergency Medicine Tutorials. Archived from the original on 2011-09-14.

- S2CID 10467377.

- ^ PMID 29851032.

- ^ Ballesteros JR, Garcia-Tarriño R, Ríos M, Domingo A, Rodríguez-Roiz JM, Llusa-Pérez M, García-Ramiro S, Soriano-Viladomiu A. (2016). "Necrotizing soft tissue infections: A review". International Journal of Advanced Joint Reconstruction. 3 (1): 9.

- S2CID 38589136.

- JSTOR 4018245. Archived from the original(PDF) on December 2, 2007.

- PMID 8557070.

- ^ Dixon, Bernhard (11 March 1996). "Microbe of the Month: What became of the flesh-eating bug?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "Moorad's life changed by rare disease". Major League Baseball. Archived 2009-09-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Don Rickles was politically incorrect before it was incorrect. And at 90, he's still going". The Washington Post. 2016-05-25. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- ^ "Cornell Discusses His Recovery from Necrotizing Fasciitis with Reporters". Archived 2013-01-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "In Memoriam – Alexandru A. Marin (1945–2005)" .Archived 2007-05-06 at the Wayback Machine. ATLAS eNews, December 2005 (accessed 5 November 2007).

- ^ Alan Coren (20 December 2006). "Before I was so rudely interrupted". The Times. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011.

- ^ R. W. Johnson (6 August 2009). "Diary". London Review of Books. Archived 2009-08-03 at the Wayback Machine. p. 41

- ^ "Slayer Guitarist Jeff Hanneman: Official Cause Of Death Revealed – May 9, 2013". Blabbermouth.net. Roadrunner Records. 2013-05-09. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "The Plastinated Man". rifters.com. Archived from the original on 20 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ "Pain of Salvation To Release 'In The Passing Light Of Day' Album In January". Blabbermouth.net. InsideOut Music. 2016-11-10. Archived from the original on 2017-01-12. Retrieved 10 Jan 2017.

- ^ "Pain of Salvation Frontman Daniel Gildenlöw On Recovering From Flesh-Eating Infection". bravewords.com. InsideOut Music. Archived from the original on 2017-01-11. Retrieved 10 Jan 2017.

- ^ Risto Mets (23 March 2015). Täna Keskerakonna initsiatiivil kokku kutsutud pressikonverentsil Tartu ülikooli kliinikumis anti ülevaade Edgar Savisaare tervislikust seisundist" [Today, at the press conference convened at the initiative of the Center Party at the Tartu University Clinic, an overview of Edgar Savisaare's health condition was given] (in Estonian). Tartu Postimees. Archived 2016-03-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Alex Smith's comeback: Inside the fight to save the QB's leg and life". espn.com. May 2020.

- ^ "A timeline of Alex Smith's remarkable comeback – from life-threatening injury to the playoffs". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Alex Smith plays in first NFL game since gruesome leg injury in November 2018". USA Today.

- ^ "E60 Documents NFL QB Alex Smith's Courageous Recovery From Gruesome Leg Injury". ESPN Press Room. 28 April 2020.

External links

- Necrotizing fasciitis at Curlie

- LRINEC Score Online