Nemegtomaia

| Nemegtomaia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specimen tentatively assigned to Nemegtomaia, Central Museum of Mongolian Dinosaurs

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Oviraptoridae |

| Subfamily: | † Heyuanninae

|

| Genus: | †Nemegtomaia Lü et al., 2005 |

| Type species | |

| †Nemegtomaia barsboldi Lü et al., 2005

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Nemegtomaia is a

Nemegtomaia is estimated to have been around 2 m (7 ft) in length, and to have weighed 40 kg (85 lb). As an

dinosaurs.The nesting Nemegtomaia specimen was placed on top of what was probably a ring of eggs, with its arms folded across them. None of the eggs are complete, but they are estimated to have been 5 to 6 cm (2 to 2.3 in) wide and 14 to 16 cm (5 to 6 in) long when intact. The specimen was found in a

History of discovery

In 1996 the Japanese palaeontologist Yoshitsugu Kobayashi (as part of the "Mongolian Highland International Dinosaur Project" team) found an incomplete skeleton of an

In 2004 Lü and colleagues determined that the skeleton belonged to a new, distinct taxon, and made it the

Assigned specimens

In 2007 two new specimens of Nemegtomaia were found by the "Dinosaurs of the Gobi" expedition, and were described by the Italian palaeontologist Federico Fanti and colleagues in 2013. The first specimen, MPC-D 107/15, was found by Fanti (who nicknamed it "Mary") in the

The nesting skeleton preserves parts of the skull, both scapulae, the left arm and hand, the right humerus, the pubic bones, the ischia, the femora, the tibiae, fibulae, and the lower portions of both feet. This specimen was found less than 500 m (1640 ft) from the holotype, and was of the same size; it was assigned to Nemegtomaia due to its similar

Description

Nemegtomaia is estimated to have been around 2 m (7 ft) in length, and to have weighed 40 kg (85 lb), a size extrapolated from more completely known relatives. As an oviraptorosaur, it would have been feathered.

Skull

The skull of Nemegtomaia was deep, narrow, and short (compared to the rest of the body), and reached 179 mm (7 in) in length. It had a well-developed crest, formed by the

The jaws of Nemegtomaia were toothless, and like other oviraptorid dinosaurs, it had a short snout with a deep, robust, and somewhat

Postcranial skeleton

The neural spines of the neck (

Classification

In their 2004

In 2012 Fanti and colleagues also found Nemegtomaia to be part of Ingeniinae as a derived member, closest to Heyuannia, due to the proportions of the hands of the two new specimens (relatively short with a robust first finger). They stated that, though the presence of crests is generally associated with oviraptorines rather than ingeniines, the feature may be correlated with size and maturity. They pointed out that the nasal and frontal bones of the ingeniine Conchoraptor were pneumatic and could potentially have grown into a crest as the animal matured, though all known skeletons of that genus are of the same small size (and one specimen appears to have been fully grown).[2] The subfamily name Ingeniinae has since been replaced by the name Heyuanninae (since Ingenia was preoccupied).[15] The cladogram below shows the placement of Nemegtomaia within Oviraptoridae, according to Fanti et al., 2012:[2]

| Oviraptoridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evolution

The

Oviraptorosaurs are known from Asia (where they may have originated) and North America, and are mainly known from deposits that date from the

Palaeobiology

Reproduction

The Nemegtomaia specimen MPC-D 107/15 was found associated with a nest with eggs; its feet were placed in the centre of what was probably a ring of eggs, with the arms folded across the tops of the eggs on each side of the body, a posture similar to what is seen in other fossils of brooding oviraptorids. The collected part of the nest is about 90 cm (35 in) wide and 100 cm (30 in) long; the skeleton occupies the upper 25 cm (10 in) of the block, whereas the remaining 20 cm (8 in) is occupied by broken eggs and shells. There is no evidence of plant material in the nest, but there are fragments of undetermined bones. The nest does not preserve any complete eggs or embryos, which prevents determination of the size, shape, number, and arrangement of the eggs in the nest. It is probable that there were originally two layers of eggs below the body, and there do not appear to have been eggs in the centre of the nest. Most eggs (seven distinct eggs have been identified) and egg fragments were recovered either in the lower layer of the nest or under the skull, neck, and limbs of the specimen, and the bones either rested directly on the eggs or were within 5 mm (0.2 in) of their surfaces. That the skeleton was directly positioned on top of it shows that the nest was not completely covered by sand. Though the placement of the eggs does not suggest a specific arrangement in the nest, most other oviraptorid nests show that the eggs were arranged in pairs in up to three levels of concentric circles. The eggs of MPC-D 107/15 were therefore most likely displaced during burial, or by external factors, such as strong winds,

Oviraptorid eggs appear to have been 17 cm (6 in) long on average, and the most complete eggs found with MPC-D 107/15 are thought to have been 5 to 6 cm (2 to 2.3 in) wide and 14 to 16 cm (5 to 6 in) long when intact. The eggs are nearly identical to some that have previously been found in Mongolia, and have therefore been assigned to the

The nesting specimen was found in a

In 2018, the Taiwanese palaeontologist Tzu-Ruei Yang and colleagues identified

Various studies have suggested that several individuals would gather eggs in a single nest, and arrange them so they could be protected by one individual, possibly a male.

Diet and feeding

The diet of oviraptorids has been interpreted in various ways since the time Oviraptor was wrongly thought to have been a predator of eggs. It has been suggested that oviraptorosaurs as a whole were herbivores, which is supported by the

Longrich and colleagues concluded that due to the similarities between oviraptorids and herbivorous animals, the bulk of their diet would most likely have been formed by plant matter. Oviraptorids are found at high frequencies in the formations they are known from, similar to the pattern seen in dinosaurs that are known to be herbivorous; these animals were more abundant than carnivorous dinosaurs, as more energy was available at their lower

In 1977 Barsbold suggested that oviraptorids

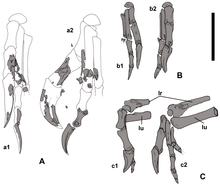

Longrich and colleagues pointed out that the robust forelimbs and enlargement of a single finger in heyuannine oviraptorids is similar to that seen in modern animals that eat ants and termites, such as anteaters and

In 2004 Lü and colleagues proposed that the articulation between the

Palaeoenvironment

Nemegtomaia is known from the Nemegt and Baruungoyot Formations, which date to the upper Campanian–lower Maastrichtian ages of the Late Cretaceous period, about 70 million years ago. Though this taxon is known only from the Nemegt locality, unidentified oviraptorid remains from other localities may belong to it. The Nemegt

The environment of the Nemegt Formation has been compared to the

Other oviraptorosaur genera known from the Nemegt Formation include the basal

Taphonomy

The nesting specimen MPC-D 107/15 has provided much information about the

Borings in the bones, burrows, and reworked sediments (perhaps caused by the construction of

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Lü, J.; Tomida, Y.; Azuma, Y.; Dong, Z.; Lee, Y.-N. (2004). "New oviraptorid dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Nemegt Formation of southwestern Mongolia" (PDF). Bulletin of the National Science Museum, Tokyo, Series C. 30: 95–130.

- ^ PMID 22347465.

- ^ a b c Lü, J., Dong, Z., Azuma, Y., Barsbold, R. & Tomida, Y. (2002). "Oviraptorosaurs compared to birds." In Zhou, Z. & Zhang, F. (eds). Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution. Beijing: Science Press. pp. 175–189.

- ^ Lü, J.; Tomida, Y.; Azuma, Y.; Dong, Z.; Lee, Y.-N.; et al. (2005). "Nemegtomaia gen. nov., a replacement name for the oviraptorosaurian dinosaur Nemegtia Lü et al. 2004, a preoccupied name". Bulletin of the National Science Museum, Tokyo, Series C. 31: 51.

- ^ a b Arbour, V.M. (2012). "Gobi Desert Diaries: Nemegtomaia Edition". pseudoplocephalus.blogspot.com. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- S2CID 4245228.

- doi:10.1139/e96-046.

- hdl:2246/3102.

- PMID 25112747.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-16766-4.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- PMID 24312233.

- ^ .

- S2CID 203880649.

- ^ a b Hendrickx, C.; Hartman, S.A.; Mateus, O. (2015). "An overview on non-avian theropod discoveries and classification". PalArch's Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology. 12 (1): 1–73. Archived from the original on 2018-06-22. Retrieved 2016-12-27.

- PMID 26000415.

- PMID 30002976.

- PMID 19095938.

- .

- S2CID 206871470.

- PMID 26401455.

- ISSN 1225-0929.

- .

- S2CID 205241353.

- ^ Lucas, S.G.; Estep, J.W. (1998). "Vertebrate biostratigraphy and biochronology of the Cretaceous of China". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 14: 1–20.

- ^ Watabe, M.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Suzuki, S.; Saneyoshi, M. (2010). "Geology of dinosaur-fossil-bearing localities (Jurassic and Cretaceous: Mesozoic) in the Gobi Desert: Results of the HMNS-MPC Joint Paleontological Expedition". Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Research Bulletin. 3: 11–18.

- .

- .