Prehistory of Transylvania

This article includes a improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (October 2010) ) |

The Prehistory of Transylvania describes what can be learned about the region known as Transylvania through archaeology, anthropology, comparative linguistics and other allied sciences.

Transylvania proper is a

Prehistory is the longest period in the history of mankind, throughout of which writing was still unknown. In Transylvania specifically this applies to the Paleolithic, Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age.[citation needed][dubious ]

| History of Romania |

|---|

|

|

|

Paleolithic

- (2,600,000 – 13,000 BP)

The

).

While an ever-increasing amount of data has become available on the evolution of the climate, fauna and vegetation of present-day

The economy of the Paleolithic communities consisted mainly of exploiting natural resources: gathering, fishing and especially hunting were the main pursuits of the diverse human groups. As early as the Lower Paleolithic, human groups either hunted or trapped game. We can assume that in Transylvania, alongside mammoths or deer, horses were a fairly important food source, if our dating of the painting on the ceiling of the cave at Cuciulat, Sălaj County, is correct.

The Lower Paleolithic in Transylvania, because data are scarce, is largely a mystery. If the discovery of an Acheulean lithic item at Căpușu Mic, Cluj County, and of several Pre-Mousterian lithic items at Tălmaciu, Sibiu County, are a certain fact, their precise stratigraphic position remains to be established. The same cannot be said about the discoveries in the Ciuc Depression at Sândominic, Harghita County, where several tools, and a rich fauna, have been encountered in certified stratigraphic positions, belonging to the geo-chronological interval covering the late Mindel to the early Riss.

The Middle Paleolithic –

The Mousterian period is closest to the alpine Paleolithic. Both periods were characterized by the presence of numerous quartzite slivers and chips, with the bones of hunted game outnumbering the tools. Consequently, specialists consider this Mousterian to be an "Eastern Charentian".

Likewise, North-Western and Northern Transylvania with the settlements at

The process of regional diversification among cultures was accelerated in the Upper Paleolithic through the middle to upper Würm. The beginnings of the Upper Paleolithic on the territory of Romania is dated somewhere between 32,000/30,000 – 13,000

The onset of the Aurignacian culture seems to have paralleled the late Mousterian

The Eastern Gravettian had a long evolution, featuring several stages of development as documented especially by the settlements in Moldova. The Gravettian has left traces in Țara Oașului and Maramureș, the sites of microlite fashioned mainly out of obsidian indicating the connection with the Gravettian in the neighboring regions (Moldavia, South-Carpathian Ukraine, Eastern Slovakia, and Northeastern Hungary).

The

Epipaleolithic and Mesolithic

- (13,000 – 9,500 BP)

The populations evolving at the onset of the

The

Besides the mammal (

The discoveries in the

Mesolithic

- (9,500 – 7,500 BP)

Specialist opinions fix the beginning of the Mesolithic era at the end of the

The

Some specialists do not exclude the possibility of identifying the

The

Neolithic

- (6600 – 3500 BC)

The

The normal divisions of the Neolithic are: Early Neolithic, Developed Neolithic, and Chalcolithic (Copper Age). The Neolithic epoch on the territory of Romania, as certified by calibrated 14C dates, began around 6600 BC, and ended around 3800–3700 BC, and no later than 3500 BC.

The Early Neolithic (c. 6600–5500 BC) consists of two cultural layers: genetically linked and with similar physiognomies. The first (layer Gura Baciului – Cârcea/Precriș) is the exclusive result of the migration of a Neolithic population from the South Balkan area, while the second (the Starčevo-Criș culture) reflects the process of adjusting to local conditions by a South Balkan community, possibly a synthesis with the local Tardenoisian groups.

The layer Gura Baciului – Cârcea, also called the

Based on the stratigraphy in the site of Gura Baciului, Cluj County, and Ocna Sibiului, Sibiu County, the development of the culture is divided into three major stages.[clarification needed] The settlements are situated on high terraces strung along secondary valleys. The dwellings are most often underground, but there are also ground level houses, usually standing on river stone platforms. Pottery (bowls, cups) is refined, with white painted dots or geometrical patterns on red or brown-red background. Concomitant with pottery, plant cultures and animal breeding, the new culture introduces implements of polished stone and the first clay statuettes. The dead are buried on the grounds of the settlements sometimes directly under the dwellings. Gura Baciului is the first site on the territory of Romania attesting incineration as a funerary practice.

At Ocna Sibiului, at Precriș, level II, a small conical stone statuette was found, with a shape representing a couple embracing, and a

Starčevo-Criș culture

The

Dwellings were set up on meadows,

The

The

In Banat, with the end of the Vinča A2 stage there emerges the

The charred seeds found in the

Turdaș culture

The Vinča communities that advanced on the middle course of the

The preservation by some Starčevo-Criș communities of painted pottery, in addition to the Vinča elements, engendered[

Chalcolithic

The Chalcolithic, Eneolithic or Copper Age (c. 4600/4500 – 3800/3700 BC) is characterized by an ever-increasing number of copper items, as well as the presence of stone, bone, horn and baked clay utensils. It marks the first production of heavy copper tools and moulds, (axes – chisels and axes), in close conjunction with the exploitation of copper deposits in Transylvania. Gold is used for ornaments and the fashioning of such idols as those at Moigrad in the Bodrogkeresztúr-Gornești culture. The craft of pottery reaches a peak, exemplified by the great number of exquisitely decorated pots.

Cultures typical for this period are the Cucuteni-Ariușd, Petrești, Tiszapolgár-Românești and Bodrogkeresztúr-Gornești. The first two cultures are among the numerous Eneolithic cultures with pottery painted in bi- and tri-chromatic patterns.

At Ariușd, Covasna County, in the east of Transylvania, the first systematic excavations were undertaken in what is considered the neo-Eneolithic epoch in Romania. The material discovered has been integrated into the greater painted pottery complex of Cucuteni-Ariușd-Tripolie.

Petrești culture

The Petrești culture diffused across almost all of Transylvania, is regarded as local in origin by some specialists, and as a migration originating from the southern areas of the Balkans, by others. It is primarily known for its painted decoration – patterns painted in red, brown-red, later brown, on a brick-red background, which testifies to the high standard of civilization of the bearers of this culture. The ornamental motifs consist in bands, rhombuses, squares, spirals, and windings. The typical forms are bowls, tureens, high stands. Plastic art is fairly scarce and so are brass items.

Decea Mureșului culture

The end of this culture [clarification needed] has been associated with the entry into central Transylvania by the bearers of the Decea Mureșului culture/horizon and the Gornești culture.

The graves at Decea Mureșului, according to some, are a continuation of the rituals of Iclod, whereas according to others, they are hard proof of the penetration of central Transylvania by a north-Pontic population. The presence of red ochre scattered over the skeletons, or laid at their feet in the form of little balls, as well as other ritual elements find better analogies, however, in the necropolis at Mariupol in south Ukraine.

Gornești culture

The Gornești culture, characterized by the occurrence of the so-called high-necked milk pots with two small protuberances pulled at the margin and drilled vertically, is a continuation of the [Românești] (featuring receptacles with bird bill protuberances and decorated with step[clarification needed] or nettle incisions), in turn descended from the Tisa culture in the developed Neolithic period.

The settlements of the neo-Eneolithic cultures were located on the low or high river terraces, on hilltops or hillspurs and consisted in several dwellings whose positions sometimes observed particular rules. Recent research has tended to focus on the defense systems (ditches and scarps) of these sites. The culture strata are thick and superposed forming at times regular tells.

The dwellings of this period were of several types. The earth houses displayed an oval shaped hole, with a maximum of 5–6 metres (16–20 ft) and a minimum of 3 m (9.8 ft) in diameter. On one of the edges a simple fireplace was built out of a smoothed layer of clay. The thatched roof was conical or elongated and was supported by a

Neo-Eneolithic sculpture is represented by cultic figures, idols, and talismans fashioned out of bone, stone or clay. These are human or animal representations conveyed by stylized or exaggerated body parts. Among the thousand anthropomorphous statues discovered, the female ones, symbols of fertility and fecundity, prevail by far.

Copper was first used for fashioning small implements or ornaments (needles, awls, fishing hooks, pendants, etc.), while gold was used solely for aesthetic and decorative purposes. For a long time the items were produced by the technique of hammering, for the technique of the casting mould as well as that of "cire perdue" (lost wax) emerged much later. Although there is no proof of the provenance of the first metal items, they are seemingly local rather than imported products. That does not necessarily suggest that metallurgy was the invention of the local population, for it might have been introduced as a result of contact with regions where metal processing had started earlier (in the East or the Caucasus).

The Eneolithic marked a notable advancement in the development of metallurgy. Throughout this period copper artifacts are present in the settlements, in grave inventories or even in deposits (assemblies of whole or fragmentary objects concentrated in one, usually isolated, place). This period also marks a high incidence of flat axes, pins, simple or multi-spiral bracelets or necklaces. The most complex of all Eneolithic achievements is the axe. These weapon-implements are bound to[clarification needed] the late phases of the Cucuteni, Decea Mureșului, and Bodrogkeresztúr-Gornești cultures. The gold Eneolithic items, outnumbered by the copper, actually constitute the beginning of goldsmithing in the Transylvanian lands. An outstanding artifact was the great gold pendant in the thesaurus of Moigrad, Sălaj County, which is 30 cm (12 in) in height and weighs 750 g (26 oz).

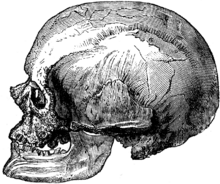

We know little about the racial types of the Transylvanian Neolithic population. The area of some of the cultures, for instance Cucuteni, lack funeral finds, for they are the expression of ritual practices that elude archeological methods. The little anthropological data available (

The role of the invasion of the

In conclusion, the Eneolithic was a period of stability, in which the sedentary populations created a spectacular civilization.

Bronze Age

- (3200) 2700–1100 BC)

For a long time the Romanian Bronze Age had been divided into four periods, but the archeological facts have imposed in the last decades the use of a three-part system: Early, Middle, and Late Bronze.

As communities acquired the secrets of alloying brass and arsenic, tin, zinc, or lead, achieving the first items in bronze, the long period during which stone constituted the main raw material for fashioning implements and weapons was coming to an end. The emergence and development of bronze metallurgy is accompanied by numerous substantial changes in economic and social life, in the spiritual life, and in the arts. The ensemble of these modifications – archeologically identifiable especially midway in the Bronze Age, yet already prefigured early on in the transition period from the Eneolithic to the Bronze Age – indicates a civilization far more sophisticated than we had imagined.

Baden culture, Coțofeni culture

The first stage of the

During the second stage, in the center of Transylvania there develops a cultural group bearing the name of the locality of

Finally, the third stage is the least known, and is characterized by the use of ceramics with brush decorations and textile impressions.

Non-ferrous metallurgy in Early Bronze Age, given the substantial fall in production as compared to the Eneolithic, should be regarded as undergoing some sort of realignment, or repositioning, rather than indicating an acute decline. The causes of this phenomenon are many and diverse (exhaustion of the usual mineral sources, major technological changes, disturbing ethnic reshuffling, etc.). Significantly, the first bronze items (brass alloyed with arsenic, and later tin) now emerged.

The

Periam-Pecica/Mureș culture

This culture occupied the Middle and

Otomani culture

The late period of the Bronze Age brings to Transylvania a marked process of cultural uniformity, whose direct manifestation is the local variety of the

groups.Ceramics are the prehistoric artifacts that have been available in the greatest quantity and variety, thus providing the foundation of all of the above-mentioned cultural classifications.

The pattern repertoire of these cultures is abstract and geometric. The Wietenberg, Otomani and

Most remarkable in this context were the super-elevated handles, shaped into ram heads, of a large size receptacle found south of the Carpathians, at Sărata Monteoru, Buzău County. The motif is repeated in markedly stylized forms on numerous pot handles of the Wietenberg culture. They were abstract to the extent that an animal was represented by a single defining element, for example a ram's horns. The same culture exhibits two rare achievements: a fragment of a cult wagon, exquisitely decorated, with both extremities ending in protomes, shaped as sheep-goat heads, discovered at Lechința de Mureș, Mureș County, and a gold axe displaying a fine engraving of a human silhouette next to a bovine silhouette, whose provenance is the thesaurus of Țufalău, Covasna County.

Close scrutiny of the production technique of the more complex vessels—the perfect duct[clarification needed] of some complex decoration patterns—strengthens the probability that the ceramics were produced by specialists. This does not exclude the possibility that other social groups, mainly children and adolescents, performed a secondary role. The transport of receptacles over long distances, in the absence of good roads, must have been an equally difficult operation, requiring itinerant craftsmen or special workshops near the more important centers.

The partial representations, the schematic physiognomies, as well as the faithful thematic rendering, though rare, all speak of a new symbolic expression that dominated the art of statuettes too. The moulding of the

The importance of the settlements, as a constructed and limited human space for the prehistoric population, is graphically suggested by Mircea Eliade,[citation needed] when he interprets them as symbolic of the "centre of the world". The analyzed archeological sites evolved from simple groupings of lodges to complex urban facilities, directed towards maintaining collective lifestyle quality, ensuring the protection of life and goods, and meeting specific social, economic, defense and cultic needs.

Thus, there are central sites, with long-term developments, epicenters of a larger territory (

Prior to this[

The animal economy of the Bronze Age, with the familiar local variations, was based on pig, sheep and goat breeding, with a decline in large horned cattle. Thus, the inhabitants of the Vatina and Otomani cultures seem to have focused on breeding swine, sheep, goats, and on intensive hunting; while among the Wietenberg and Noua communities cattle were most common, used both for food and for traction, followed by sheep, goats, swine and horses. Horses were constantly present and revolutionized transportation and communication. The wagon with big wheels, later with spikes, emerged and spread, either as a warring and hunting vehicle, or to symbolize social status.

Monteoru culture

The food provided by agriculture and animal breeding was supplemented by hunting and fishing. Their proportion within the economy varied among the communities of the

There is no clear indication whether agriculture or animal breeding predominated within Bronze Age communities, with research revealing that both were being practiced together within the same area. But as populations stabilized, they tended towards a pastoral East and a farm-dominated West.

Men became more economically productive, due to improved metallurgy and better animal husbandry, and the use of draught animals in agriculture. Men acquired a dominant position within the family and in society.

For the Bronze Age people, the mountains provided hunting,

The unique direct proof of prehistoric exploitation of non-ferrous metals in Transylvania is the stone axe found in a gallery in

Furthermore, the

Increasingly, traces of people involved in bronze-related activities are found. There are finished or semi-finished items,

The most complete and spectacular data related to metal processing workshops gathered so far, although partial, come from

The conversion of minerals to metal by means of fire was a process accompanied by rituals, magic formulas, and chanting to bring about the "birth of the metal". At the foundation of a kiln at

The mass of the

The scarcity of settlements with metallurgic activity also hints at the possible existence of itinerant

The first level with gift depositaries[

Wietenberg culture

The thesaurus found in 1840 at

There certainly existed many wooden tools or receptacles, but they have not been preserved. Animal skin processing for fashioning clothing items, shields, harnesses, etc. must have been widespread.

The Bronze Age

Archeological investigations alone are too few and disparate for a detailed reconstruction of the religions of the Bronze Age people. The solar symbols, dynamic or static in form, (continuing spirals, simple crosses or crosses with spirals, spiked wheels, rays, etc.) are so numerous that they could be illustrated in a separate volume, and speak clearly about the prevailing role of this cult.

The symbolic value of the items and their number speak for themselves. The walls were decorated with

All of these practices, judging by the archeological data mentioned above, as well as being based on other analogies, were accompanied by offerings,

In the Wietenberg culture area at

The link between the

The glass in the

In the same era, the metals produced on the slopes of the eastern arch of the

The marked expansion of pan-European trade in middle and late Bronze Age created growing dependence between the different cultural groups, and an acceleration of uniformity in cultural values and produce. All of which sped up the general development of society and the passage to a new phase in historical evolution.

Noua culture

The

The differences identified between the deposits of the period speak not of unitary series,[

Only a small number of bronze items were found in settlements and cemeteries. Most of them have a fortuitous appearance in what we call deposits. Romanian archaeology has interpreted their storage as a proof of troubled times, yet today a new interpretation is gaining ground: they are cultic deposits functioning as offerings, or at times, as the result of prestigious inter-community auctions of the "potlatch" type. The arguments in favour are strong: long periods of peaceful development, the location of the deposits (confluence of rivers, lakes, springs, clearings, mild slopes looking east, etc.), the number of items, the arrangements, their manipulations (fired, bent, fragmentation through bending, etc.), etc. Moreover, there is no logic in the locals burying their arms in the face of a military threat.

The multiplication of the offensive, in contrast to the defensive, fighting equipment (swords type Boiu – Sauerbrunn, battle axes with spiked disc, daggers, spearheads, arm bracers, all made of bronze), the development of settlements with man-made defenses, the existence of distinct warrior graves, gives the impression that the Bronze Age was a warring world. But there are numerous arguments that it was really a matter of parading rather than using force.

The extraordinary

The local

Iron Age

- (1100 BC – 150 AD)

The First

The defining phenomenon of the epoch is the use of iron with a paramount impact on humanity's subsequent evolution.

Geto-Dacians

In contrast to the

Over 600 sites are known so far across the territory of Transylvania from the First Iron Age. Most sites were occupied during all stages of this epoch. Twenty-six

The fortified settlements and the refuge fortifications were usually located on inaccessible elevations and close to water courses and fertile areas. Their sizes vary with the location and its possibilities. For instance, the

), each measuring 30 hectares, count among the largest in Europe. The first Iron Age fortifications are also known in the county of Cluj, in Dej, Huedin and Someşul Rece.The defense systems surrounding these regular

, the last of which was designed as a wooden wall erected on the ridge of the rampart representing the most important part of the system. So designed, the fortifications generally measured 7–8 m in height, but could reach 10-12 making them difficult to conquer.As tribal centers, the fortified settlements had multiple functions, the foremost of which was to ensure the defense of the community. The discovery of

The large quantity of bones discovered in the settlements, most originating from domestic animals, cattle, sheep,

Finally, besides some such crafts as metallurgy which imply special skill, members of every family engaged in a series of activities such as weaving, spinning, and leather dressing, shown by the discovery in the dwellings of spindle, spools, sewing needles, and scrapers for cleaning hide.

The occurrence of

Religion was demonstrably a daily presence in prehistoric communities. Thus, besides the magic practice and the

During the First Iron Age, the local culture was influenced by neighboring areas. Midway through the epoch, on the middle course of the Mureș there arrived from Banat elements of a culture called Basarabi. Displaying ceramics with specific decorations (incised and impressed), the culture was assimilated by the autochthonous background.

Subsequently, at the beginning of the late period of this epoch (6th century BC), a group of

See also

- Ancient history of Transylvania

- Bronze Age in Romania

- Celts in Transylvania

- Dacia

- History of Romania

- History of Transylvania

- La Tène culture

- List of cities in Thrace and Dacia

- List of tribes in Thrace and Dacia

- National Museum of Transylvanian History

- Prehistory of Europe

- Prehistory of Romania

- Rotbav Archaeological Site

References

Sources

- I. Andrițoiu, Civilizația tracilor din sud-vestul Transilvaniei în epoca bronzului, București, 1992

- T. Bader, Epoca bronzului în nord-vestul Transilvaniei. Cultura pretracică și tracică, București, 1978

- T. Bader, Die Schwerter in Rumänien, PBF IV, 8, Stuttgart, 1991

- M. Bitiri, Paleoliticul în Ţara Oașului, București, 1972

- I. Bóna, Die mittlere Bronzezeit Ungars und ihre südöstlichen Beziehungen, Budapest 1975

- N. Boroffka, Die Wietenberg-Kultur. Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der Bronzezeit in Südosteuropa, Bonn, 1994

- N. Chidioşan, Contribuții la istoria tracilor din nord-vestul României. Aşezarea de la Derșida, Oradea, 1980

- M. Cârciumaru, Le Paléolithique en Roumanie, Grenoble, 1999

- Fl. Drașoveanu, Cultura Vinća târzie (faza C) în Banat, Timișoara, 1996

- V. Dumitrescu, A. Vulpe, Dacia înainte de Dromihete, București, 1988

- V. Dumitrescu, Arta preistorică in România, București, 1974

- A. C. Florescu, Repertoriul culturii Noua – Coslogeni din România. Aşezări şi necropole, BiblThrac 1, Călărași, 1991

- F. Gogâltan, Bronzul timpuriu și mijlociu în Banat și pe cursul inferior al Mureșului, Timișoara, 1999

- K. Horedt, Die Wietenbergkultur, Dacia, NS, IV, 1960, 107-137

- C. Kacsó, Beiträge zur Kenntnis des Verbreitunsgebietes und der Chronologie der Suciu de Sus-Kultur, Dacia N.S. 31, 1987, 51-75

- B. Kacsó, Die späte bronzezeit im Karpaten-Donau-Raum (14.-9. Jahrhundert v. Chr.), in Thraker und Kelten beidseits der Karpaten, Cluj-Napoca, 2000, 31-41

- T. Kovács, L'Age du Bronze en Hongrie, Budapest, 1977

- Gh. Lazarovici, Neoliticul în Banat, Cluj-Napoca, 1980

- Gh. Lazarovici, Z. Maxim, Gura-Baciului. Monografie arheologică, Cluj-Napoca, 1995

- A. S. Luca, Cultura Bodrogkeresztúr, Alba Iulia, 1998

- F. Mogoşanu, Paleoliticul din Banat, București, 1978

- S. Morintz, Contribuţii arheologice la istoria tracilor timpuriiI. Epoca bronzului în spaţiul carpato-balcanic, București, 1978

- I. Ordentlich, Contribuția săpăturilor de pe "Dealul Vida" (comuna Sălacea, jud. Bihor) la cunoașterea culturii Otomani, Satu Mare, 2, 1972, 63-84

- I. Paul, Cultura Petrești, București, 1992

- I. Paul, Vorgeschichtliche Untersuchungen in Siebenburgen, Alba Iulia, 1995

- Al. Păunescu, Evoluția uneltelor și armelor de piatră cioplită descoperite pe teritoriul României, București, 1970

- Al. Păunescu, Paleoliticul, Epipaleoliticul, Mezoliticul, in Istoria Românilor, București, 2001

- M. Petrescu-Dâmboviţa, Depozitele de bronzuri din România, București, 1977

- P. Roman, Cultura Coțofeni, București, 1976

- P. Roman, I. Nemeti, Cultura Baden in România, București, 1978

- M. Rotea, Mittlere Bronzezeit im Carpaten-Donau-Raum (14.-9. Jahrhundert v. Chr.), in Thraker und Kelten beidseits der Karpaten, Cluj-Napoca, 2000, 22-30

- M. Rotea, Pagini din Preistoria Transilvaniei. Epoca Bronzului. Cluj Napoc. 2009

- M. Rotea, Prehistory. In: The History of Romania, Bucuresti 2008

- M. Roska, Erdély régészeti repertóriuma, Cluj, 1941

- M. Rusu, Consideraţii asupra metallurgiei aurului din Transilvania în Bronz D şi Hallstatt A, AMNapocensis, IX, 1972, 29-63

- T. Soroceanu, Studien zur Mureș-Kultur. Mit Beiträgen von V. V. Morariu, M. Bogdan, I. Ardelean und D. Săbădeanu und Mitarbeit von Ortansa Radu, Internationale Archäologie 7, Erlbach, 1991

- T. Soroceanu, Die Fundumstände bronzezeitlicher Deponierungen. Ein beitrag zur Hortdeutung beiderseitder Karpaten, in T. Soroceanu (Hrsg.), Bronzefunde in Rumänien, PAS 10, Berlin 1995, 15–80.

- N. Ursulescu, Neoliticul, Eneoliticul, in Istoria Românilor, București, 2001

- N. Vlassa, Neoliticul Transilvaniei. Studii, articole, note, BMNapocensis III, Cluj-Napoca, 1976

- A. Vulpe, Die Äxte und Beile in Rumänien I, PBF IX, 2, München, 1970

- A. Vulpe, Die Äxte und Beile in Rumänien II, PBF IX, 5, München, 1975

- A. Vulpe, Epoca bronzului, in Istoria Românilor, București, 2001,