League of the Islanders

The League of the Islanders (

History

The history of the League of the Islanders is relatively obscure, as no literary sources about it have survived. The only evidence comes from inscriptions.

The islands remained under Ptolemaic control until sometime in the middle of the 3rd century BC. The last documents pertaining to the League date approximately to the second quarter of the century; no nēsiarchos is attested after c. 260 BC, and the number of Ptolemaic offerings to Delos also drops off sharply at the same time. This indicates that the League collapsed, and the Ptolemies lost control of the Aegean, either during the

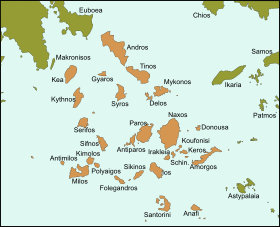

In the meantime, Rhodes rose to become the chief naval power in the Aegean and even beyond. In order to protect their political and commercial interests, such as the grain trade, where Rhodes held a dominant position, the Rhodians were active against pirates such as Demetrius of Pharos or the Cretan cities and the Aetolian League; both of the latter secretly sponsored by King Philip V of Macedon. By c. 220 BC, according to Polybius (The Histories, IV.47.1), the Rhodians "were considered the supreme authority in maritime matters" and were called upon by merchants to intervene in cases such as the imposition of tolls by the Byzantines on passage of ships through the Bosporus.[13] In 201 BC, during the Cretan War, Philip V of Macedon subdued the Cyclades at the head of his fleet, but already in the next year, the Rhodians took over of most of the islands except for the Macedonian-garrisoned islands of Andros, Paros, and Kythnos.[14] Followed by further Macedonian setbacks in the Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC), the Cycladic islands, already bound individually to Rhodes by treaties of alliance, were soon after—an exact date cannot be ascertained—formed into a "Second Nesiotic League" under the hegemony of Rhodes.[15][16] The motivations for Rhodes' move are unclear, but the historian Kenneth Sheedy has suggested that they stemmed at least partly from a desire to preempt other powers, whether the Kingdom of Pergamon or the Roman Republic, from establishing control over the area.[17] Unlike the original League however, the Second League appears to have been a more voluntary association.[18] The Second Nesiotic League is commonly held to have lasted until the end of Rhodian independence at the conclusion of the Third Macedonian War in 167 BC,[3] but Sheedy suggests that it may have started to disintegrate earlier, as the Rhodians focused their attention on maintaining their grip over their Asian holdings and could no longer afford to maintain the costly hegemony over the Cyclades.[19]

Institutions

The League's institutions are well attested through a series of inscriptions for its Ptolemaic period, but it appears that the main characteristics were present already under Antigonus, and according to

The League was headed by the nēsiarchos (νησίαρχος, "ruler of the islands") and a council (συνέδριον,

The League's centre in Antigonid and Ptolemaic times was the sacred island of Delos, where the annual festivals were held, and where the synedrion assembled—a single, and probably exceptional, convocation by the Ptolemaic commander

The nēsiarchos was appointed by the League's suzerain king, and, again in contrast to most other such leagues, was not an islander. He wielded executive power and was responsible for carrying out the synedrion's decisions, collect the member states' contributions, command the League military, and safeguard shipping in the Aegean.

References

- ^ a b Merker 1970, p. 141.

- ^ Billows 1990, p. 220.

- ^ a b c d e f Schwahn 1931, col. 1263.

- ^ Billows 1990, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Merker 1970, p. 142.

- ^ a b c Billows 1990, p. 221.

- ^ Merker 1970, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Reger 1994, p. 34.

- ^ Reger 1994, p. 33.

- ^ Reger 1994, pp. 34, 41–43.

- ^ Reger 1994, pp. 34, 39–40, 43–46.

- ^ Reger 1994, pp. 33–35, 46–65.

- ^ Sheedy 1996, pp. 430–431.

- ^ Sheedy 1996, p. 428.

- ^ Reger 1994, p. 35.

- ^ Sheedy 1996, pp. 423–425, 426–428.

- ^ Sheedy 1996, pp. 428–449.

- ^ Sheedy 1996, pp. 448–449.

- ^ Sheedy 1996, pp. 447–449.

- ^ a b Billows 1990, p. 222.

- ^ Kolbe 1930, pp. 20–29.

- ^ Merker 1970, pp. 158–159.

- ^ a b c Billows 1990, pp. 221–222.

- ^ a b Schwahn 1931, col. 1263–1264.

- ^ Merker 1970, pp. 156–157.

- ^ a b c Merker 1970, p. 157.

- ^ a b c d e Schwahn 1931, col. 1264.

- ^ a b Schwahn 1931, col. 1265.

- ^ Merker 1970, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Merker 1970, pp. 150–153.

- ^ Merker 1970, p. 153.

- ^ Schwahn 1931, col. 1264–1265.

Sources

- ISBN 0-520-20880-3.

- Kolbe, Walther (1930). "The Neutrality of Delos". JSTOR 626160.

- König, Werner (1910). Der Bund der Nesioten; ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Kykladen und benachbarten Inseln im Zeitalter des Hellenismus. Halle: Wischan & Brukhardt.

- Meadows, Andrew (2013). "The Ptolemaic League of the Islanders". In Buraselis, Kostas; Stefanou, Mary; Thompson, Dorothy J. (eds.). The Ptolemies, the Sea and the Nile: Studies in Waterborne Power. Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–38. ISBN 9781107033351.

- Merker, Irwin L. (1970). "The Ptolemaic Officials and the League of the Islanders". JSTOR 4435128.

- Reger, Gary (1994). "The Political History of the Kyklades 260–200 B.C.". JSTOR 4436314.

- Schwahn, Walther (1931). "Sympoliteia". Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft. Vol. Band IV, Halbband 7, Stoa–Symposion. col. 1171–1266.

- Sheedy, Kenneth A. (1996). "The Origins of the Second Nesiotic League and the Defence of Kythnos". JSTOR 4436440.

- Tarn, William Woodthorpe (1911). "Nauarch and Nesiarch". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 31: 251–259.

- Marchesini, Mattia (2017). Il Koinon dei Nesioti (PDF).