Church of the East in China

The Church of the East (also known as the Nestorian Church) historically had a presence in China during two periods: first from the 7th through the 10th century in the Tang dynasty, when it was known as Jingjiao (Chinese: 景教; pinyin: Jǐngjiào; Wade–Giles: Ching3-chiao4; lit. 'Luminous Religion'), and later during the Yuan dynasty in the 13th and 14th centuries, when it was described alongside other foreign religions like Catholicism and possibly Manichaeism as Yelikewen jiao (Chinese: 也里可溫教; pinyin: Yělǐkěwēn jiào).

After centuries of hiatus, the first Assyrian Church of the East Divine Liturgy was celebrated in China in 2010.[1]

Tang dynasty

History

Two possibly Church of the East monks were preaching

The first recorded Christian mission to China was led by the Syriac monk known in Chinese as Alopen. Alopen's mission arrived in the Chinese capital Chang'an in 635, during the reign of Emperor Taizong of the Tang dynasty. Taizong extended official tolerance to the mission and invited the Christians to translate their sacred works for the imperial library. This tolerance was followed by many of Taizong's successors, allowing the Church of the East to thrive in China for over 200 years.[2][3]

China became a

Church of the East worshippers in the time of Xuanzong accepted the Confucian religious beliefs of the emperor, and likely other traditional Chinese religions.[6]

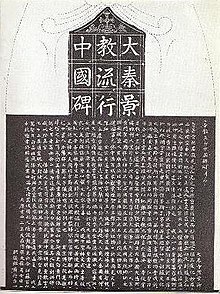

In 781 the Christian community in Chang'an erected a tablet known as the Xi'an Stele on the grounds of a local monastery. The stele contains a long inscription in Chinese with Syriac glosses, composed by the cleric Adam, probably the metropolitan of Beth Sinaye. The inscription describes the eventful progress of the Church of the East mission in China since Alopen's arrival. The inscription also mentions the archdeacons Gigoi of Khumdan [Chang'an] and Gabriel of Sarag [Lo-yang]; Yazdbuzid, 'priest and country-bishop of Khumdan'; Sargis, 'priest and country-bishop'; and the bishop Yohannan. These references confirm that the Church of the East in China had a well-developed hierarchy at the end of the 8th century, with bishops in both northern capitals, and there were probably other dioceses besides Chang'an and Lo-yang.

Nestorian Christians like the Bactrian Priest Yisi of Balkh helped the Tang dynasty general Guo Ziyi militarily crush the An Lushan rebellion, with Yisi personally acting as a military commander. Yisi and the Church of the East were rewarded by the Tang dynasty with titles and positions as described in the Xi'an Stele.[7][8][9][10][11][12]

It is unlikely that there were many Christian communities in

Epitaphs were found dating from the Tang dynasty of a Christian couple in Luoyang of a Church of the East Christian Sogdian woman, who Lady An (安氏) who died in 821 and her Church of the East Han Chinese husband, Hua Xian (花献) who died in 827. These Han Chinese Christian men may have married Sogdian Christian women because of a lack of Han Chinese women belonging to the Christian religion, limiting their choice of spouses among the same ethnicity.[15] Another epitaph in Luoyang of a Nestorian Christian Sogdian woman also surnamed An was discovered and she was put in her tomb by her military officer son on 22 January, 815. This Sogdian woman's husband was surnamed He (和) and he was a Han Chinese man and the family was indicated to be multiethnic on the epitaph pillar.[16] In Luoyang, the mixed-race sons of Nestorian Christian Sogdian women and Han Chinese men had many career paths available to them. Neither their mixed ethnicity nor their faith were barriers and they were able to become civil officials or military officers and openly profess their Christian religion and support Christian monasteries.[17]

Decline

In 845, a decree issued by Emperor Wuzong demanded that foreign religions like Buddhism and Christianity be cast out of the kingdom. The decree required that Christians be forced to return to laity and become taxpayers.[18] The decree had tremendously negative effects on the Christian community and later imperial decrees calling for religious toleration likely had no effect for the Christians, who were likely severely marginalized or extinct by then.[18]

The province of Beth Sinaye is last mentioned in 987 by the Arab writer Ibn al-Nadim, who met a Church of the East monk who had recently returned from China, who informed him that 'Christianity was just extinct in China; the native Christians had perished in one way or another; the church which they had used had been destroyed; and there was only one Christian left in the land'.[19] The collapse of the Church of the East in China coincided with the fall of the Tang dynasty, which led to a tumultuous era (the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period).[3]

The eventual extinction of Christianity has been attributed to factors such as that the religion had a minority status and was of foreign character along with dependance on imperial support.[20] The majority of Christians in Tang China were of foreign origin or descent (mostly from Persia and Central Asia). The religion had relatively little impact on the native Han Chinese.[21] A decisive factor to the collapse of the Church of the East was the church's reliance on Tang imperial protection and patronage to continue to operate undisturbed. After the fall of the Tang dynasty, what was left of the church quickly vanished without such support.[20]

Literature

Dozens of Jingjiao texts were translated from Syriac into Chinese. Only a few have survived. These are generally referred to as the Chinese

Yuan dynasty

The

History

The Church of the East had significant evangelical success under the

and the destruction of the Abbasid caliphate which saw the execution of the last Abbasid caliph and the slaughter of 800,000-2,000,000 Arab Muslim civilians in Baghdad, with only the Nestorian Assyrian Christians being spared.The rise of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty in the 13th century allowed the church to return to China, and rise to a greater status than it had ever had before.[31] However, this was primarily among foreigners.[32][33] By the end of the century, two new metropolitan provinces had been created for China: Tangut and 'Katai and Ong'.[34]

The province of Tangut covered northwestern China, and its metropolitan seems to have sat at

The province of Katai (

During the first half of the 14th century there were Church of the East Christian communities in many cities in China, and the province of Katai and Ong probably had several suffragan dioceses. In 1253

The relationship between the Catholic

Decline

The Church of the East declined in China substantially in the mid-14th century. Several contemporaries, including the papal envoy

Reasons often cited for the rapid decline and disappearance of Church of the East after the fall of the Yuan dynasty include the foreign character of the religion and its adherents, comprising mainly a Central Asian and Turkic-speaking immigrant community.[43] There was also a paucity of native Han Chinese converts, a lack of Chinese translations of the Bible, and a heavy political reliance on patronage by the Yuan imperial court.[43] In consequence of these factors, once the Yuan dynasty fell, the Church of the East in China quickly became marginalized and soon vanished, leaving little trace of its existence.[43]

Modern China (20th century-present)

In 1998, the

See also

- Xi'an Stele

- Daqin Pagoda

- Jingjiao Documents

- Rabban Bar Sauma

- Yahballaha III

- Ongud

- Keraites

- Church of the East in Sichuan

- Mogao Christian painting

- Murals from the Christian temple at Qocho

References

- ^ a b "The Return to China". Assyrian Church News. 2010-10-07. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ Moule, Christians in China before the Year 1550, 38

- ^ a b Moffett, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Mai, Scriptorum Veterum Nova Collectio, x. 141

- ^ Wilmshurst, The Martyred Church, 123–4

- ^ Li, Dun J. (1965). The Ageless Chinese: A History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 373.

- S2CID 164239427.

- ISBN 978-3-643-90329-7.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISSN 1754-517X.

- ISBN 978-1-78672-316-1.

- .

- ISBN 978-1-351-67277-1.

- ISBN 978-3-643-90754-7.

- ISBN 978-1-78453-683-1.

- ^ Morrow, Kenneth T. (May 2019). NEGOTIATING BELONGING: THE CHURCH OF THE EAST'S CONTESTED IDENTITY IN TANG CHINA (PDF) (DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY OF IDEAS). THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS. pp. 109–135, viii, xv, 156, 164, 115, 116.

- ^ Morrow, Kenneth T. (May 2019). NEGOTIATING BELONGING: THE CHURCH OF THE EAST'S CONTESTED IDENTITY IN TANG CHINA (PDF) (DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY OF IDEAS). THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS. pp. 155–156, 149, 150, viii, xv.

- ^ Morrow, Kenneth T. (May 2019). NEGOTIATING BELONGING: THE CHURCH OF THE EAST'S CONTESTED IDENTITY IN TANG CHINA (PDF) (DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY OF IDEAS). THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS. p. 164.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-60833-162-8.

- ^ Wilmshurst, The Martyred Church, 222

- ^ ISBN 978-1-60833-162-8.

- S2CID 164412254.

- ^ P. Y. Saeki, The Nestorian Documents and Relics in China, pp. 248-265

- ^ "Chinese Nestorian Documents from the Tang Dynasty". Archived from the original on 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ISBN 978-1-300-43531-0.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ISBN 978-962-937-140-1.

- ISBN 978-90-04-18997-3.

- S2CID 225038696.

- ^ "Florence Hodous | Semantic Scholar".

- ^ "Florence Hodous | Independent Scholar - Academia.edu".

- ^ Adler, Joseph A. (2005). "Chinese Religions: An Overview". Department of Religious Studies at Kenyon College. Gambier, Ohio: Kenyon College. Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- Eastern Orthodox Metropolitanate of Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. Archived from the originalon 2022-09-21.

- ^ Lau, Hua Teck (2003). "The Cross and the Lotus". Church and the Society. 26 (2): 90.

- ^ Fiey, POCN, 48–9, 103–4 and 137–8

- ^ Bar Hebraeus, Ecclesiastical Chronicle, ii. 450

- ^ Wallis Budge, The Monks of Kublai Khan, 127 and 132

- ^ Bar Hebraeus, Ecclesiastical Chronicle, ii. 452

- ^ Lieu, S., Manichaeism in Central Asia and China, 180

- ISBN 978-3-447-06580-1.

- ^ Yule and Cordier, Cathay and the Way Thither, iii. 31–3 and 212

- ^ Nau, 'Les pierres tombales nestoriennes du musée Guimet', ROC, 18 (1913), 3–35

- ^ Moule, Christians in China before the Year 1550, 216–40

- ^ ISBN 978-3-447-06580-1.

- ^ "Biography of HH Mar Gewargis III". Assyrian Church News. 2015-09-28. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ^ "Bishop Mar Awa Royel Visits China". Assyrian Church News. 2012-12-10. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

Further reading

- ISBN 978-1-134-43019-2.

- ISBN 978-3-515-05718-9.

- Lieu, Samuel N. C. (1997). Manichaeism in Central Asia and China. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10405-4

- Moffett, Samuel Hugh (1999). "Alopen". Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-8028-4680-8.

- Malek, Roman; Peter Hofrichter, eds. (2006). Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Sankt Augustin: Institut Monumenta Serica. ISBN 3-8050-0534-2.

- Moule, Arthur C., Christians in China before the year 1550, London, 1930

- Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Louvain: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-0876-5.

- Wilmshurst, David (2011). The martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East. London: East & West Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-907318-04-7.

This article incorporates text from The Chinese repository, Volume 13, a publication from 1844, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The Chinese repository, Volume 13, a publication from 1844, now in the public domain in the United States.