New Amsterdam Theatre

Herts & Tallant | |

| Structural engineer | DeSimone Consulting Engineers |

|---|---|

| Website | |

| newamsterdamtheatre | |

| Architectural style(s) | Beaux-Arts, Art Nouveau |

| Designated | January 10, 1980 |

| Reference no. | 80002664[1] |

| Designated entity | Theater |

New York City Landmark | |

| Designated | October 23, 1979[2] |

| Reference no. | 1026[2] |

| Designated entity | Facade |

New York City Landmark | |

| Designated | October 23, 1979[3] |

| Reference no. | 1027[3] |

| Designated entity | Interior |

The New Amsterdam Theatre is a

The theater's main entrance is through a 10-story wing facing north on 42nd Street, while the auditorium is in the rear, facing south on 41st Street. The

The New Amsterdam Theatre was named for the Dutch settlement of

Site

The New Amsterdam Theatre is at 214 West

The

The surrounding area is part of

Design

The New Amsterdam Theatre was designed by architects

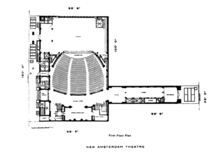

The theater consists of a 10-story tower with offices, on the narrow 42nd Street frontage,[25][a] and an auditorium at the rear, on 41st Street.[25][26] The tower was developed to house Klaw and Erlanger's booking activities.[9][27] The two sections are connected by a one-story passageway at ground level. The New Amsterdam Theatre's building housed two theaters when it opened: the main 41st Street auditorium as well as a rooftop theater.[28][29]

Facade

The primary

Theater entrance

On 42nd Street, the triple-height arch had rusticated stone piers on either side.[30] The original entrance was a double door with transom windows made of leaded glass, above which was a sign with the theater's name.[35] The sign was ornately decorated and, at night, was illuminated by lights on the upper stories.[27] The second and third stories contain bronze-framed windows with flower and vine decorations.[18] The original doors were removed around 1937, but the second- and third-story windows still exist.[35] The entrance vestibule, originally immediately inside the doors, contained green tiles and relief panels by St. John Issing. The vestibule was reconfigured as an outdoor space when the original entrance doors were removed; it contains a ticket booth on its western side.[36]

The arch at the second and third stories was initially highly decorated, but the decorations were all removed in 1937 to make way for a marquee.[37] At the second floor were yellow-and-gray Montreal marble columns.[31] These were topped by bronze capitals designed by Enid Yandell, which contained four heads depicting the ages of drama. The top of the arch at the third story originally had a keystone carved by Grendellis and Ricci, with a garland depicting oak, laurel, and ivy.[30][31][32] Above was a cornice with modillions, as well as a group of sculptures by George Gray Barnard, depicting five figures linked by garlands.[18][31][38] Cupid (symbolizing love comedy) and a woman stood on one side of the central figure, a female personification of drama; Pierrot (symbolizing musical farce) and a knight stood on the other side.[31][32][38]

Office stories

The office stories along the 42nd Street elevation are three

The tenth story contains a central projecting dormer, containing a decorated pediment, as well as a smaller dormer in either of the side bays. The peak of the central dormer contains a mask with garlands.[30] It was originally flanked by representations of drama and music.[30][32] These figures held up a shield silhouetted against the sky.[31][32] Herts & Tallant did not include a cornice on the facade,[39] since they felt such a feature was unsuitable for office buildings.[40]

Interior

The New Amsterdam Theatre was among the first non-high-rise buildings in New York City with a steel superstructure.[23] The structural frame is made of 2,000 short tons (1,800 long tons; 1,800 t) of steel.[34][41] According to a 1903 source, the frame is made of approximately 270,000 steel pieces, which required about 7,500 engineering drawings. There were also 57 cantilevers and 38 electric elevators.[34] The side walls of the office wing are non-bearing walls.[40] The tower wing was used as offices for Klaw and Erlanger and later Florenz Ziegfeld Jr.[42]

The theater was also mechanically advanced for its time, with heating, cooling, and vacuum-cleaning systems, as well as a fireproof structural frame.[43][44] The auditorium alone had a volume of 400,000 cu ft (11,000 m3) and was indirectly heated by fans in the subbasement. The ventilation system included air plenums on 41st Street, a 10-foot (3.0 m) fan, a silk filter, and a heater that moistened the air to natural levels of humidity. The air could be completely changed in ten minutes.[45] Air was distributed through the floors and walls,[46] and it was exhausted through disc fans above the auditorium.[45] Three telephone systems were installed to allow communications between different parts of the theater.[47] These mechanical systems were completely replaced between 1995 and 1997.[48] The new mechanical systems do not intrude upon the original design, except for a light grid above the proscenium of the auditorium.[49]

Lobby and foyers

Leading from the 42nd Street entrance vestibule is the lobby, which runs under the office wing; the space contains curving Art Nouveau-style floral motifs.

The lobby leads south to the auditorium's entrance foyer.[51][53] Within the foyer, above the doors from the lobby, is a semicircular plaster relief by Hugh Tallant, depicting progress.[38][54][55][56] This design includes a blue-and-gold representation of a woman with flower and leaf decorations on either side.[53] Perry designed full-size panels for the foyer walls, which depicted the colony of New Amsterdam in the 17th century as well as a more modern view of New York City in the 19th century.[38][53][54][56][b] The panels were subsequently removed when refreshment stands were added,[36] and mirrors were installed in their place.[53] The ceiling of the foyer contained a stained-glass dome, originally named "The Song of the Flowers".[46][53][54][c] The stained glass vault was replaced with a vault painted gold.[53]

The south wall of the entrance foyer leads to a promenade foyer, which is as wide as the auditorium itself.[55][57] The promenade foyer contains a groin vault with floral moldings.[53] The foyer contains a wood balustrade overlooking the parterre orchestra level of the auditorium to the west.[58] A sylvan-themed relief by Issing is at the southern end of the promenade foyer, leading to 41st Street.[59]

On the east wall of the promenade foyer, there are four staircases: two leading up to the auditorium's balconies and two leading down to the lounges.

Rooms

From the rear of the first-floor promenade foyer is an arch leading to the general reception room, a green-and-gold space with oak paneling.[59] The general reception room measures 50 ft × 30 ft (15.2 m × 9.1 m).[61] The arch was originally flanked by marble fountains.[62] On the north and south walls, George Peixotto designed two symbolic paintings entitled "Inspiration" and "Creation".[32][63] The rear (east) wall of the reception room has a fireplace with a Caen stone and Irish marble mantel, also decorated with curving foliate patterns. Above the fireplaces are niches, which originally contained busts depicting poets Homer, Shakespeare, and Virgil.[59] The paneling is 12 ft (3.7 m) high and contains built-in seats and stylized curved trees.[64] The paneling also once had 38 medallions with painted portraits, designed by William Frazee Strunz and depicting "Lovers of Historical Drama".[63] The reception room's vaulted ceiling and the room's arches are decorated with floral moldings.[51][53]

The women's and men's lounges are both directly below the reception room: the women's lounge to the south and the men's lounge to the north.

The old rectangular smoking room, also called the New Amsterdam Room for its decorations, is between the lounges.

Auditorium

The auditorium is at the south end of the building and is elliptical in plan, with curved walls, a domed ceiling, and two balcony levels over the orchestra level.[51][68][61] The space measures 86 ft (26 m) wide, and it is 90 ft (27 m) long between the stage apron and the reception room's wall. The dome rises 80 ft (24 m) above the floor of the orchestra.[61][69][70] The original color scheme was described in The New York Times as consisting of "tender pinks, mauves, lilacs, red and gold".[32][71] These decorations were bright to compensate for the original direct current lighting system, which was dim. The modern decorative scheme contains reproductions of many of the original decorations with a subdued color palette.[72] A double wall surrounds the whole auditorium and contains a fire gallery measuring 15 ft (4.6 m) wide.[73][74] The auditorium held around 1,550 seats in its original configuration.[75][d] After its reopening in 1997, the auditorium had 1,814 seats;[76][77] as of 2022[update], the New Amsterdam has a seating capacity of 1,702.[78][e]

Unusually for theaters of the time, the balconies are cantilevered from the structural framework, which eliminated the need for columns that blocked sightlines.

The auditorium initially had twelve seating boxes, six on either side of the stage;[32][61][75] they were arranged in staggered pairs and installed within arches on the side walls.[74] The boxes were included to compensate for the relative lack of seating on the side walls,[80] and they had unobstructed views of the stage.[39] Each box was ornamented with a different floral motif,[32][82][83] so the boxes were often identified by the names of the flowers on them.[74] The boxes were removed when the New Amsterdam was converted into a movie theater.[75][82] They were restored in 1997 based on historical blueprints.[72][83]

The Neumark brothers designed plaster and carved-oak moldings around the dome, the proscenium arch, and the wall arches.[58] The proscenium arch measures 36 ft (11 m) high and 40 ft (12 m) wide.[69][70] Surrounding the proscenium is an elliptical arch, which rises to the edge of the ceiling dome.[69] Between the two arches is a 18-by-45-foot (5.5 by 13.7 m) mural, designed by Robert Blum and executed by Albert B. Wenzell after Blum died.[32][38][69] The mural depicts personified figures of such topics as truth, love, melancholy, death, and chivalry,[68] flanking a central figure representing poetry.[32][38] On either side are murals by Wenzell depicting Virtue and Courage.[71] Issing also designed 16 dark-green peacocks for the proscenium, placed atop depictions of vines.[68][70] There are also floral motifs and female figures around the dome.[58] The ceiling of the auditorium also has seven arches with wood paneling.[26][69] The ceiling of the main auditorium contains a girder measuring 90 ft (27 m) long and 14 ft (4.3 m) tall and weighing 70 short tons (63 long tons; 64 t).[23][41][84] At the time of the New Amsterdam's construction in 1903, this was the largest piece of steel ever used in a building.[23][73]

The stage measures 60 by 100 ft (18 by 30 m),

Roof theater

The girder above the main auditorium supported a roof theater named the Aerial Gardens.[84][87] Accessed by two elevators from the lobby,[74] the Aerial Gardens was also designed by Herts & Tallant and opened in 1904.[15][16] New York City building regulations at the time prohibited the construction of buildings above theater stages. As a result, the back of the theater's stage wall was directly above the proscenium arch of the main auditorium, and the stage was smaller.[87] There was no balcony, but there were twelve boxes as well as a promenade at the rear of the roof theater.[34] The Aerial Gardens was fully enclosed[88] and originally had 680 seats.[89] It could theoretically be used year-round, but in practice it was only used during the summer.[90] There was also a planted garden adjacent to the theater.[34] The Aerial Gardens was subsequently known as Ziegfeld Roof, Danse de Follies, Dresden Theatre, Frolics Theatre, and finally the New Amsterdam Roof.[91]

After Florenz Ziegfeld started hosting the Ziegfeld Follies at the New Amsterdam in 1913, the main floor of the roof theater was turned into a 22,000-square-foot (2,000 m2) dance floor, and a U-shaped balcony was erected.[92] The redesigned roof theater had a movable stage and a glass balcony.[89][93] Cross lighting could also be used to create rainbow color patterns.[93] In 1930, a movable glass curtain was installed over the proscenium of the roof theater.[94][95][96] The floor was soundproofed when the space was used as an NBC broadcast studio, and smaller studios were placed in the office wing.[96] By the early 21st century, the roof theater had been converted into office space.[97][98]

History

Times Square became the epicenter for large-scale theater productions between 1900 and the Great Depression.[99] Manhattan's theater district had begun to shift from Union Square and Madison Square during the first decade of the 20th century.[2][100] The New Amsterdam, Lyceum, and Hudson, which all opened in 1903, were among the first theaters to make this shift;[101] the New Amsterdam is one of the oldest surviving Broadway theaters.[102] Furthermore, at the beginning of the 20th century, Klaw and Erlanger operated the predominant theatrical booking agency in the United States.[103] They decided to relocate to 42nd Street after observing that the Metropolitan Opera House, the Victoria Theatre, and the Theatre Republic (now New Victory Theater) had been developed around that area.[27]

Construction

In January 1902, Klaw and Erlanger bought seven land lots at 214 West 42nd Street and 207–219 West 41st Street. At the time, the theater was to be known as the Majestic.[7][8] The next month, Fuller Construction was hired as the main contractor,[17] and Herts & Tallant were selected as the architects for the theater.[27][104] By then, the venue had been named the New Amsterdam, after the Dutch colonial settlement that predated New York City.[27][104] Herts & Tallant submitted plans to the New York City Department of Buildings (DOB) shortly afterward.[105][106] Construction had commenced by May 1902.[107][108] Eighteen steam drills and 150 workers excavated the foundation to a depth of 40 ft (12 m).[109]

A controversy arose in early 1903 when a neighboring landowner, Samuel McMillan, discovered that the office wing on 42nd Street would protrude 4 ft (1.2 m) beyond the lot line.[110][111] The DOB ordered that work be halted temporarily, pending a decision on an ordinance regarding "ornamental projections".[111] The New York City Board of Aldermen had already passed the ordinance, and mayor Seth Low had to decide whether to approve it. The DOB stationed a police officer outside the construction site during the daytime, but the developers erected the facade overnight in March 1903.[111] A meeting on the ordinance drew much public opposition, prompting Low to send the bill back to the Board of Aldermen.[112] A judge placed an injunction in April 1903, preventing Low from making a decision on the ordinance.[113][114] The injunction was vacated two days afterward, and Low vetoed the resolution.[115] The Board of Aldermen passed a revised resolution the next week; the aldermen explicitly stated that the ordinance would help Klaw and Erlanger.[116]

After the ordinance was passed, the New Amsterdam's facade was completed as planned.[110] By July 1903, work was proceeding on the New Amsterdam full-time, which The New York Times attributed to an agreement between the Fuller Company and the building trades.[117] At the beginning of that August, the steel structure was topped out.[118] The dispute over the facade continued even after the theater's opening. In 1905, McMillan brought the lawsuit to the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, which ruled that the Board of Aldermen's ordinance violated the Constitution of New York.[119]

Original Broadway run

1900s and early 1910s

The New Amsterdam Theatre opened on October 26, 1903,

The Aerial Gardens opened on June 6, 1904, with the vaudeville production A Little of Everything.[88][128] The New Amsterdam had started out as a venue for serious drama,[110] but comedy drama became popular within a few years of its opening.[129] Klaw and Erlanger had begun renting out the New Amsterdam, since they wanted to focus on other theatrical ventures, and since it was expensive for them to produce all of the theater's shows.[130] Many producers expressed interest in the theater because of its technologically advanced equipment and Art Nouveau design.[130] The men disagreed over the theater's bookings; Klaw wanted to stage classical productions, but Erlanger preferred large revues and musicals.[123] In 1905, the theater hosted the comedy She Stoops to Conquer.[131][132] The next year, the theater hosted Forty-five Minutes from Broadway, featuring Fay Templeton and Victor Moore,[19][133][134] as well as The Governor's Son, starring the family of George M. Cohan.[131][135] This was followed in 1907 by The Merry Widow,[19][133][136] which ran 416 performances[19][137] at both the main auditorium and the Aerial Gardens.[131] Richard Mansfield appeared in a limited number of performances at the theater for several seasons,[123][131] starring in both Richard III[129][138] and Peer Gynt.[110][139] Kitty Grey, starring Julia Sanderson, was staged at the New Amsterdam in 1909,[110][140] as was the European operetta The Silver Star.[131][141]

The New Amsterdam also staged musicals, particularly those imported from Europe,[130] as well as classic hits.[19] The productions included those by Shakespeare, as well as "kiddie fare" such as Mother Goose and Humpty Dumpty.[75] In 1910, the New Amsterdam staged the melodrama Madame X[19][131][142] and the European operetta Madame Sherry,[131][143] the latter of which ran 231 performances.[19][144] The next year saw a production of The Pink Lady with Hazel Dawn,[133][145] running 312 performances,[19][146] as well as the musical adaptation of Ben-Hur.[147][148] The New Amsterdam hosted several other productions in 1912 and 1913, including Robin Hood,[149][150][151] The Count of Luxembourg,[149][152][153] and Oh! Oh! Delphine.[131][154]

Ziegfeld Follies era

Flo Ziegfeld hosted the Ziegfeld Follies, a series of revues, at the New Amsterdam every year from 1913 to 1927, with two exceptions.[155][156][g] Ziegfeld's relationship with Klaw and Erlanger had dated to the mid-1900s, when the syndicate had paid him $200 a week to present vaudeville; by 1907, he had come up with the Follies.[159] The first edition of the Follies at the New Amsterdam was hosted on June 16, 1913.[149][160][161] Among the performers in the Follies were Fanny Brice, Eddie Cantor, W. C. Fields, Ina Claire, Marilyn Miller, Will Rogers, Sophie Tucker, Bert Williams, and Van and Schenck.[155] An urban legend holds that the theater contains the ghost of one performer, silent film star Olive Thomas.[162][163][164] Ziegfeld also hired either Joseph Urban[28][159] or John Eberson to redesign the theater on the roof with a balcony and a dance floor.[89][94] With the completion of the roof theater's renovation, Ziegfeld began displaying Danse de Follies, a racier sister show of the Follies, in 1915.[149][28][165] Subsequently, known as the Midnight Frolic,[89][149][166] the show was also used to test the skills of promising up-and-coming performers.[166] Ziegfeld also had his own office on the seventh floor of the office wing.[167] The 1924 edition of the Follies had the longest run, with 401 performances, though that edition was not particularly distinctive either critically or artistically.[168]

Between each year's edition of the Follies, the theater hosted other productions.

The New Amsterdam staged

Late 1920s and 1930s

Klaw and Erlanger continued to operate the New Amsterdam Theatre jointly until 1927, when Erlanger bought out Klaw's interest. Erlanger then announced plans to renovate the New Amsterdam Theatre for $500,000.[203][204] The same year, Ziegfeld developed his own theater, the Ziegfeld Theatre on Sixth Avenue.[156] The theater's hits in 1928 included the musical comedy Rosalie,[194][205] which ran 327 performances,[206][207] and Whoopee,[208][209] which ran 379 performances.[206][210] Meanwhile, Ziegfeld re-launched the Midnight Frolic at the rooftop theater in December 1928.[211][212] The following June, Erlanger announced he would convert the rooftop theater into a modern facility called Aerial Theater, which would accommodate legitimate plays, films with sound, or radio broadcasts.[213] Upon obtaining sole ownership of the theater, Erlanger renewed Dillingham and Ziegfeld's lease, which had been set to expire at the end of 1929.[214] Another production was staged at the main auditorium in 1929, Sherlock Holmes.[215][216] Erlanger was in significant debt when he died in 1930, and the Dry Dock Savings Bank took over his estate.[217]

In the 1930s, during the beginning of the Great Depression, many Broadway theaters were impacted by declining attendance. The main auditorium only saw a small decrease in quality and quantity of productions, but the Frolics Theatre had a steep decline in premieres.

When Revenge with Music premiered at the New Amsterdam in 1934,[238][239][240] it was the only remaining legitimate theater production on 42nd Street.[229][241] Revenge with Music was followed by George White's Scandals of 1936,[225][238][242] as well as Sigmund Romberg's Forbidden Melody the same year.[243][244][245] The Dry Dock Savings Bank acquired the New Amsterdam Theatre through a foreclosure proceeding in May 1936 after the theater's owners had failed to pay over $1.65 million in interest, taxes, and other fees.[246][247] By then, Erlanger and Ziegfeld had died several years previously.[229] Afterward, Dry Dock leased the roof to CBS and the Mutual Broadcasting System for broadcasts, but an injunction was placed in August 1936 because Dry Dock had no broadcast license.[248] The broadcasters had to apply for a license after Dry Dock unsuccessfully sued to have the injunction removed.[249][250] Othello, which premiered in January 1937,[251][252] was the last live performance at the New Amsterdam for more than half a century;[225][251] it ran for 21 performances before closing.[217][253]

Movie theater and decline

The New Amsterdam Theatre was sold in June 1937 to Max A. Cohen of Anco Enterprises,[254][255][h] under the condition that the New Amsterdam never host burlesque.[217][251] Cohen renovated the facade, replacing the original decorations with a marquee.[37][126] The New Amsterdam reopened as a movie theater on July 3, 1937, showing the film adaptation of A Midsummer Night's Dream.[239][256] Bernard Sobel, Flo Ziegfeld's former agent, lamented in The New York Times that the cinema conversion was "another indication that the old order has indeed changed".[257] The theater showed other movies for 10 to 25 cents per ticket, although Cohen could not show first runs of movies immediately upon their release, at least not initially.[217] The marquee was further modified in 1947.[75] The auditorium boxes were removed[82][126] as part of a 1953 renovation.[75] These modifications allowed the installation of a Cinerama wide screen.[48][72][258]

MBS continued to use the rooftop theater as a studio.

In 1960, Mark Finkelstein, who co-owned the theater building with Cohen, announced that the roof theater would be renovated into a 700-seat venue for theatrical productions.

Restoration

The 42nd Street Development Corporation, formed in 1976 to discuss plans for redeveloping Times Square, considered turning the New Amsterdam Theatre into a dance complex in 1977.

Nederlander plans

The

Plans for restoration were officially announced in May 1983.[285] The $6 million project would use both private and public funding.[273][286] Soon after work began, contractors discovered more structural damage than they had expected, including rotting girders.[67][287][288] This led the Nederlanders to announce in mid-1983 that the reopening would be delayed indefinitely.[288] The production of the musical Carmen, which was supposed to be presented at the roof theater, was relocated as a result.[251][287][288] The Nederlanders wanted to seal off the roof theater completely,[273] but the city government suggested instead that the National Theater Center be hosted on the roof.[273][286] City officials indicated that they would provide $2.5 million to restore the roof theater and convert it to the National Theater Center, but the city allocated the funds elsewhere in the 1985 city budget.[289]

The Empire State Development Corporation and New York City Economic Development Corporation purchased the property in 1984.[290] The same year, Jerry Weintraub purchased a stake in the operation of the New Amsterdam.[291] The theater's renovation had been planned in conjunction with four new office towers, the development of which had been delayed.[126] The renovation was abandoned partway through, the decorations being left exposed to the elements.[72][126][217] The roof had started leaking, and the interior had water damage.[126][217][287] Several shows were announced for the rundown theater, all of which were withdrawn.[292] After having spent $15 million on renovations, the Nederlanders announced in 1990 that the New Amsterdam's restoration would not be viable "for the next several years" until the four office towers were completed.[67] The New York City Opera considered moving to the theater in 1991[293] but decided against doing so.[67]

After the Nederlanders fell behind on their payments in 1992, the UDC agreed to take over the theater for $247,000[217] or $275,000.[67][76][294] Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates (HHPA) was hired to stabilize the structure.[48][251] By then, chunks of plaster had fallen from the roof and first balcony, and entire sections of the roof theater had fallen apart.[67] Bird droppings had appeared all over the floor because there were holes in the roof.[287] There were dead cats in the basement, and mushrooms were growing through the auditorium floor.[295] A reporter for the Los Angeles Times wrote in 1994 that the theater's "cracking terra-cotta ornaments, faded murals and decayed plaster moldings [form] a depressing metaphor for the decline of Times Square".[296]

Disney renovation

Marian Sulzberger Heiskell, a chairwoman of the 42nd Street Development Project, was a family friend of Michael Eisner, the chairman of The Walt Disney Company. For several years in the 1980s and 1990s, Heiskell had tried to convince Eisner to open a Disney enterprise on Times Square. Disney's internal studies showed that such a venue would conflict with the gated and clean image of its amusement parks and other venues.[297][298] Architect Robert A. M. Stern, who had worked both on Disney projects and on the 42nd Street Development, tried to convince Eisner but was rebuffed.[297][299] In March 1993, Eisner changed his mind and asked to see a full-size model of the buildings being planned in the 42nd Street Development.[297] At a meeting to discuss designs for the town of Celebration, Florida,[300] Stern arranged for Eisner to tour the theater.[297][301] Eisner quickly agreed to renovate the theater after New 42nd Street president Cora Cahan guided him through the dilapidated interior.[83]

In September 1993, the media reported that Disney was seriously considering renovating the New Amsterdam Theatre.[70][302] Disney had planned to show Beauty and the Beast there, but delays forced the production to open at the Palace Theatre instead.[303] Disney had tentatively agreed to take over the New Amsterdam by the end of the year,[83][304] and mayor Rudy Giuliani and governor Mario Cuomo publicly announced plans for the theater's restoration in January 1994.[296][305] Disney real estate negotiator Frank S. Ioppolo Sr. obtained several guarantees after threatening to withdraw from the project. This included protection against lawsuits over the proposed renovation; expensive, high-quality items; and government subsidies from the state and city.[295] Other Broadway theater operators had initially opposed the economic incentives, alleging the 42nd Street Development Project was tantamount to a subsidy for the New Amsterdam.[306] After Cuomo promised to create a loan program for other Broadway theaters, two operators dropped their opposition to Disney's project.[305]

Disney promised in February 1994 to renovate the theater with $8 million of its own equity and a $21 million low-interest loan from the city and state governments.[76][307] Other entertainment companies showed interest in the 42nd Street redevelopment after the agreement was announced,[70][308] and there was also interest in renovating 42nd Street's other theaters.[309] During 1994, the rundown theater was used as a filming location for the movie Vanya on 42nd Street.[287][310] Officials agreed to loan Disney another $5 million later that year.[295] In May 1995, Disney Theatrical Productions signed a 49-year revenue-based lease for the property,[311][312] in which Disney would pay the city and state a percentage of the gross sales from the theater.[309] Disney, along with the city and state governments, ultimately agreed to share any costs above $32.5 million. Disney would also pay about $2 million for higher-quality materials, and the city and state governments would commit $1.9 million to a contingency fund.[295] The financial plan was finalized in July 1995.[313] Disney wanted at least two other companies to commit to new developments in Times Square before it agreed to restore the New Amsterdam.[314] After.the recent high-profile cancellations of the Disney's America and WestCOT theme parks, Disney Development vice president David A. Malmuth wanted a successful development.[295] Madame Tussauds and AMC Theatres subsequently agreed to redevelop three neighboring theaters.[314]

Disney's

Disney operation

The New Amsterdam's restoration was officially completed on April 2, 1997.[319] Architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote "If this is Disney magic, we need more of it",[77][320] and Herbert Muschamp wrote: "The place is an architectural version of an American Eden, the unsullied natural paradise in which European explorers cast the New World."[320][321] The first production was a limited engagement of a concert version of King David that May,[322][323] followed by the premiere of the film Hercules the following month.[324] Disney's decision to stage these events was to ensure the New Amsterdam's restoration would not be overshadowed by the premiere of The Lion King, which in itself was a highly acclaimed production.[320] The Lion King opened in November 1997.[322][325] The roof theater remained closed, and Disney had no plans to reopen it,[326] in part because the elevators could not accommodate 700 patrons under city building codes.[327] Disney had converted the roof theater into office space by the early 21st century.[97][98] The renovation of the theater was detailed in the book The New Amsterdam: The Biography of a Broadway Theater.[322][328]

Disney's restoration of the New Amsterdam Theatre helped spur the long-delayed redevelopment of Times Square; this led to criticisms of the area's "Disneyfication" from observers who were unaware of Disney's investment.[329] Besides theatrical productions, the revived New Amsterdam has hosted events benefiting Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, including past iterations of the annual Easter Bonnet Competition.[330] It also hosted a televised concert by the Backstreet Boys for Disney Channel, Backstreet Boys In Concert, in 1998.[331] The Lion King ran at the New Amsterdam until June 2006, when it relocated to the Minskoff Theatre to make way for Mary Poppins.[332] Mary Poppins began previews at the New Amsterdam on October 14, 2006, and had its first regular performance on November 16, 2006;[333] it ran until March 3, 2013.[333][334]

Previews for the musical Aladdin began on February 26, 2014, and the show officially opened on March 20, 2014.[335] Aladdin broke the house record at the New Amsterdam Theatre for the week ending August 10, 2014, with a gross of $1,602,785.[336] As of 2023[update], Aladdin also holds the box-office record for the New Amsterdam Theatre, grossing $2,584,549 over nine performances for the week ending December 30, 2018.[337] All Broadway theaters temporarily closed on March 12, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[338] The New Amsterdam reopened September 28, 2021, with performances of Aladdin.[339]

Notable productions

Productions are listed by the year of their first performance. The Ziegfeld Follies, which have had multiple editions, are listed by the years of the first performances of each edition. This list only includes Broadway shows; it does not include films screened there.[340][341]

- 1903: A Midsummer Night's Dream[120][342]

- 1903: Whoop-Dee-Doo[23][124]

- 1903: Mother Goose[343]

- 1904: The Two Orphans[344]

- 1905: She Stoops to Conquer[131][345]

- 1905: Richard III[129][138]

- 1906: Forty-five Minutes from Broadway[133][346]

- 1907: The Merry Widow[133][137]

- 1907: Peer Gynt[110][347]

- 1909: The Silver Star[141]

- 1910: Madame X[131][348]

- 1911: The Pink Lady[19][146]

- 1911: Ben-Hur[147][148]

- 1912: The Count of Luxembourg[153]

- 1913: Oh! Oh! Delphine[131][154]

- 1913–1927:[g] Ziegfeld Follies[155][i]

- 1913: Sweethearts[170][350]

- 1914: Watch Your Step[129][174]

- 1918:

- 1920: Sally[187][351]

- 1925: Sunny[194][196]

- 1927:

- 1928: Rosalie[194][207]

- 1928: Whoopee[208][353]

- 1930:

- 1931: The Band Wagon[225][355]

- 1932: Face the Music[225][356]

- 1933: Alice in Wonderland[227][230]

- 1933: The Cherry Orchard[233]

- 1933: Roberta[225][357]

- 1934: Revenge with Music[187][358]

- 1936: George White's Scandals[225][242]

- 1937: Othello[225][253]

- 1997: King David[49][323]

- 1997: The Lion King[325]

- 2006: Mary Poppins[333]

- 2014: Aladdin[359]

See also

- List of Broadway theaters

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References

Notes

- ^ Margolies 1997, p. 117, gives a conflicting figure of 11 stories.

- ^ National Park Service 1980, p. 4, wrote that the main panel depicted the 1900s.

- ^ National Park Service 1980, p. 4, referred to the dome as "A Song of Flowers".

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 705, says the auditorium had 1,537 seats.

- ^ According to seating charts, the orchestra has 698 seats, the first balcony has 586 seats, and the second balcony has 418 seats.[78]

- ^ Sometimes cited as 52 by 100 ft (16 by 30 m)[85]

- ^ a b In 1921, the Follies was hosted at the Globe Theatre because the New Amsterdam was hosting Sally.[157] The 1926 Follies were skipped.[158]

- ^ Contemporary New York Times and New York Herald Tribune articles report that the theater was sold for $1.05 million;[254][255] Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 103, states that the theater was sold for $1.5 million.[217]

- ^ Including the Ziegfeld Follies of 1919[349]

Citations

- ^ a b "Federal Register: 46 Fed. Reg. 10451 (Feb. 3, 1981)" (PDF). Library of Congress. February 3, 1981. p. 10649 (PDF p. 179). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 1.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 1.

- ^ a b c "214 West 42 Street, 10036". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- New 42nd Street. Archived from the original(PDF) on July 7, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 571161767.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 4.

- ^ "MTA Neighborhood Maps: Times Sq-42 St (S)". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2018. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ New York City, Proposed Times Square Hotel UDAG: Environmental Impact Statement (Report). United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1981. p. 4.15.

- ProQuest 1505606157.

- ^ a b c Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 675.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8129-3107-5.

- ^ a b "Contracts Awarded". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 69, no. 1769. February 8, 1902. p. 256. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 6; National Park Service 1980, pp. 2, 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, p. 211.

- ^ Waters 1903, p. 488.

- ^ a b National Park Service 1980, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bloom 2013, p. 187.

- ^ Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, p. 212.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 4; National Park Service 1980, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Margolies 1997, p. 117.

- ^ a b c d e f Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d Morrison 1999, p. 41.

- ^ Bloom 2013, p. 187; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 5; National Park Service 1980, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f Waters 1903, p. 490.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 1980, p. 13.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 6; National Park Service 1980, p. 2.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 1980, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The New Amsterdam Theatre". Architects' and Builders' Magazine. Vol. 5, no. 5. February 1904. pp. 186–192. Archived from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "New Amsterdam Theatre, Des. Herts & Tallant". New York Plaisance ... : an Illustrated Series of New York Places of Amusement. Vol. 1. 1908. pp. 11–12 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Waters 1903, p. 489.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, pp. 4–5.

- ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 9.

- ^ a b Gura 2015, p. 71.

- ^ a b National Park Service 1980, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 97.

- ^ a b Hancock 1903, p. 716.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 705.

- ^ a b Bloom 2013, p. 191.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d Gura 2015, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 5; National Park Service 1980, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d Waters 1903, p. 491.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 6; National Park Service 1980, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Morrison 1999, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Morrison 1999, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 6; National Park Service 1980, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 7; National Park Service 1980, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hancock 1903, p. 715.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 1980, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 7; National Park Service 1980, p. 5.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, pp. 7–8; National Park Service 1980, p. 6.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 7.

- ^ from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 8; National Park Service 1980, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 1980, p. 6.

- ^ ProQuest 209628710.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 9; National Park Service 1980, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f Margolies 1997, p. 116.

- ^ a b c Waters 1903, p. 492.

- ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 1980, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Margolies 1997, p. 113.

- ^ a b c Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, pp. 704–705.

- ^ ProQuest 398571103.

- ^ a b "New Amsterdam Theatre New York Seating Chart & Photos". SeatPlan. May 14, 2019. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ Bloom 2013, p. 187; Gura 2015, p. 68; Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 97; Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 9; Margolies 1997, p. 117; Morrison 1999, p. 43; National Park Service 1980, p. 7; Waters 1903, p. 491.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-911548-68-6.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1979, p. 9; National Park Service 1980, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 106.

- ^ a b Waters 1903, pp. 491–492.

- ^ a b c Henderson & Greene 2008, pp. 97–99.

- ^ a b Hancock 1903, pp. 715–716.

- ^ a b National Park Service 1980, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b Bloom 2013, p. 187; National Park Service 1980, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e "The Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic". Museum of the City of New York. July 1, 2014. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ Bloom 2013, pp. 187–188.

- ^ a b "Aerial Gardens". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ Bloom 2013, pp. 188–189.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 1980, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f Bloom 2013, p. 189.

- ^ ProQuest 758146123.

- ^ ProQuest 1113132673.

- ^ a b "6 Things We Learned on Disney's Behind the Magic Tour". NYC & Company. August 26, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Perrottet, Tony (May 9, 2015). "Traces of Ziegfeld's New York". City Room. The New York Times Company. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ Swift, Christopher (2018). "The City Performs: An Architectural History of NYC Theater". New York City College of Technology, City University of New York. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ "Theater District –". New York Preservation Archive Project. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-393-28545-1. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ "Lyceum". Spotlight on Broadway. The City of New York. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 2.

- ^ ProQuest 571180854.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ProQuest 571154546.

- ProQuest 555054865.

- ^ "New Theater Begun". The Buffalo Sunday Morning News. June 1, 1902. p. 13. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Notes". The Standard Union. July 20, 1902. p. 13. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 3.

- ^ ProQuest 1013638152.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ProQuest 571385147.

- ProQuest 571359541.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ProQuest 1013639935.

- ^ "Dramatic and Musical Notes". Times Union. August 8, 1903. p. 20. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Private Encroachment Upon Public Property Judicially Condemned". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 76, no. 1961. October 14, 1905. p. 571. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 3; National Park Service 1980, p. 2.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "The New Amsterdam A Beautiful Theatre". The Brooklyn Citizen. October 25, 1903. p. 9. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 99.

- ^ a b "Whoop-dee-doo Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"Catherine – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ National Park Service 1980, p. 15.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ "New York's Splendid New Theatres" (PDF). Theatre. Vol. 3. 1903. p. 296. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 3; National Park Service 1980, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bloom 2013, p. 188.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Bloom 2013, p. 188; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 3; National Park Service 1980, p. 14.

- ProQuest 571633856.

- ProQuest 2099375928.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "The Merry Widow Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"The Merry Widow – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ ProQuest 571651954.

- ProQuest 571782021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 572284035.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "Madame Sherry Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Madame Sherry – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "The Pink Lady Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"The Pink Lady – Broadway Musical – 1912 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ a b Botto & Mitchell 2002, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b "Ben Hur Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Ben Hur – Broadway Play – 1911 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ a b c d e f g h Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 8.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "Robin Hood Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"Robin Hood – Broadway Musical – 1912 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "The Count of Luxembourg Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"The Count of Luxembourg – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ a b "Oh! Oh! Delphine Broadway @ Knickerbocker Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"Oh! Oh! Delphine – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ a b c Bloom 2013, p. 188; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 3; National Park Service 1980, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 102.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 3; National Park Service 1980, p. 13.

- ^ a b Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 101.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ProQuest 575112753.

- ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 18.

- ^ "The Ghost of Olive Thomas". WNYC. October 31, 2016. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Bloom 2013, p. 189; National Park Service 1980, p. 8.

- ^ a b National Park Service 1980, pp. 14–15.

- ^ ProQuest 1284455550.

- ^ a b c d Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 11.

- ^ Bloom 2013, p. 188; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 8.

- ^ a b "Sweethearts Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Sweethearts – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ Bloom 2013, p. 188; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 8; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 3.

- ^ "See 'The Little Cafe'". The Brooklyn Citizen. December 28, 1913. p. 21. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "Watch Your Step Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Watch Your Step – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ "Around the Map Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. January 29, 1916. Archived from the original on October 1, 2022. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Around the Map – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, pp. 8–9.

- ^ "Miss Springtime Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Miss Springtime – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ a b Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 9.

- ^ "The Cohan Revue of 1918 Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 1, 2022. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"The Cohan Revue of 1918 – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ "The Rainbow Girl Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"The Rainbow Girl – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ a b Bloom 2013, p. 188; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 9.

- ^ a b "The Girl Behind the Gun Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 1, 2022. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"The Girl Behind the Gun – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ "The Velvet Lady Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"The Velvet Lady – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ a b Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 10.

- ^ "Monsieur Beaucaire Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Monsieur Beaucaire – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ a b c Bloom 2013, p. 189; National Park Service 1980, p. 15.

- ProQuest 576284787.

- ^ "Sally Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. September 17, 1923. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Sally – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ProQuest 576411535.

- ProQuest 1666212787.

- ProQuest 1665980053.

- ^ a b c d e f Bloom 2013, p. 189; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 4; National Park Service 1980, p. 15.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "Sunny Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Sunny – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "Betsy Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"Betsy – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Lucky Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Lucky – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ProQuest 1114346524.

- ^ Parker, John, ed. (1947). Who's Who in the Theatre (10th revised ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd. p. 1184.

- ^ "Julius Caesar Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"Julius Caesar – Broadway Play – 1927 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ProQuest 1031840538.

- ISBN 978-0-19-974209-7. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 12.

- ^ a b "Rosalie Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. January 23, 1928. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Rosalie – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ a b Bloom 2013, p. 189; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 4.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ "Whoopee! Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Whoopee! – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ProQuest 1113613879.

- ProQuest 1111696176.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ Bloom 2013, p. 189; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 12.

- ^ "Sherlock Holmes Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"Sherlock Holmes – Broadway Play – 1929 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ a b c d e f g h i Henderson & Greene 2008, p. 103.

- ProQuest 557797201.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 1113160449.

- ^ a b c Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 13.

- ^ a b Bloom 2013, pp. 189–190.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ "The Admirable Crichton Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"The Admirable Crichton – Broadway Play – 1931 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bloom 2013, p. 190; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 4; National Park Service 1980, p. 15.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 14.

- ProQuest 1114487260.

- ^ a b c d Bloom 2013, p. 190.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ "Alice in Wonderland Broadway @ Civic Repertory Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ProQuest 100746487.

- ^ a b "The Cherry Orchard Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"The Cherry Orchard – Broadway Play – 1933 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1979, p. 4; National Park Service 1980, p. 15.

- ProQuest 1114853701.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ "Roberta Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. May 28, 1934. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

"Roberta – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021. - ^ a b Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 15.

- ^ a b Bloom 2013, p. 190; National Park Service 1980, p. 15.

- ProQuest 1221534166.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "George White's Scandals [1936] Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"George White's Scandals [1936] – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, pp. 15–16.

- ^ "Resurrection of 42nd Street". Broadway: The American Musical. PBS. September 27, 2012. Archived from the original on July 23, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ "Forbidden Melody Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"Forbidden Melody – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ProQuest 1237468220.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ProQuest 1032101395.

- ^ a b c d e Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 16.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "Othello Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"Othello – Broadway Play – 1937 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 1240438952.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Henderson 1997, p. 7.

- ProQuest 1032187655.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ProQuest 1285813415.

- ProQuest 177760009.

- ProQuest 1327244868.

- ^ ProQuest 1039939408.

- ProQuest 1327502496.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ProQuest 1014785728.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ProQuest 1325840251.

- ProQuest 1270424918.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ProQuest 511943242.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, pp. 702–704.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ProQuest 1438331408.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 962816802.

- ^ from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 964113985.

- ^ a b c d e Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 704.

- ^ ProQuest 1438382844.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Bloom 2013, pp. 190–191.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ from the original on May 11, 2023. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 702.

- OCLC 39919327.

- ^ Henderson 1997, p. 120.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ProQuest 398518642.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 219140083.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ISSN 0028-7369. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, pp. 16–17.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ProQuest 209641064.

- ^ Patterson, Maureen (April 1, 1998). "New Amsterdam Theatre". Buildings. Retrieved January 19, 2022 – via Free Online Library.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ProQuest 408734448.

- ^ a b c Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 706.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 17.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on September 4, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- from the original on July 31, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ "Programs". The Journal News. July 10, 1999. p. 32. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Mary Poppins Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

"Mary Poppins – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Gans, Andrew (September 28, 2021). "Disney's Aladdin Reopens on Broadway September 28". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 14, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Gerard, Jeremy (August 11, 2014). "Broadway B.O.: Summer Lull Still Beautiful For 'Beautiful', 'Hedwig And The Angry Inch', 'Aladdin'; Bye-Bye 'Violet'". Deadline. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ "Production Gross". Playbill. March 10, 2019. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on September 16, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "'Aladdin' Reopens At New Amsterdam Theatre". CBS New York. September 29, 2021. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

Gonzalez, Angi (September 30, 2021). "'Aladdin' resumes Broadway performances after one-day COVID-19 hiatus". Spectrum News NY1 New York City. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2021. - ^ "New Amsterdam Theatre (1903) New York, NY". Playbill. December 16, 2015. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "New Amsterdam Theatre – New York, NY". Internet Broadway Database. March 20, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "A Midsummer Night's Dream Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"A Midsummer Night's Dream – Broadway Play – 1903 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Mother Goose (Broadway, New Amsterdam Theatre, 1903)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

"Mother Goose – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. December 2, 1903. Retrieved March 27, 2024. - ^ "The Two Orphans Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"The Two Orphans – Broadway Play – 1904 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "She Stoops to Conquer Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"She Stoops to Conquer – Broadway Play – 1905 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Forty-Five Minutes from Broadway Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"Forty-five Minutes from Broadway – Broadway Play – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Peer Gynt Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"Peer Gynt – Broadway Play – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Madame X Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"Madame X – Broadway Play – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Ziegfeld Follies of 1919 – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. June 16, 1919. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

"Ziegfeld Follies of 1919 (Broadway, New Amsterdam Theatre, 1919)". Playbill. December 14, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2023. - from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "Sally Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"Sally – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Trelawny of the 'Wells'". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

"Trelawny of the "Wells" – Broadway Play – 1927 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Whoopee! Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"Whoopee! – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Earl Carroll's Vanities of 1930 Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"Earl Carroll's Vanities [1930] – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "The Band Wagon Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"The Band Wagon – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Face the Music Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"Face the Music – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Roberta Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"Roberta – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Revenge with Music Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

"Revenge with Music – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021. - ^ "Aladdin Broadway @ New Amsterdam Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 15, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

"Aladdin – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

Sources

- Bloom, Ken (2013). Routledge Guide to Broadway. Hoboken, NJ: Taylor & Francis. OCLC 870591731.

- Bloom, Ken (2007). The Routledge Guide to Broadway (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-97380-9.

- Botto, Louis; Mitchell, Brian Stokes (2002). At This Theatre: 100 Years of Broadway Shows, Stories and Stars. New York; Milwaukee, WI: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books/Playbill. ISBN 978-1-55783-566-6.

- Gura, Judith (2015). Interior Landmarks: Treasures of New York. New York: The Monacelli Press. OCLC 899332305.

- Hancock, La Touche (1903). The Theatrical Season, 1902–1903. The American Almanac, Year-book, Cyclopaedia and Atlas (1st ed.). New York: New York American and Journal; Hearst's Chicago American; San Francisco Examiner. ISSN 1063-7257.

- Henderson, Mary C. (1997). The New Amsterdam: The Biography of a Broadway Theatre. New York: Disney Editions. OCLC 37300588.

- Henderson, Mary C.; Greene, Alexis (2008). The Story of 42nd Street: the Theaters, Shows, Characters, and Scandals of the World's Most Notorious Street. New York: Back Stage Books. OCLC 190860159.

- Margolies, John (June 1997). "A Spectacular Broadway Revival, the New Amsterdam Theater Glows on 42nd Street Once Again" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 185. ISSN 0003-858X.

- Morrison, William (1999). Broadway Theatres: History and Architecture. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-40244-4.

- New Amsterdam Theatre (PDF) (Report). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. January 10, 1980.

- Pearson, Marjorie (October 23, 1979). New Amsterdam Theater (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

- Pearson, Marjorie (October 23, 1979). New Amsterdam Theater Interior (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2006). New York 2000: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Bicentennial and the Millennium. New York: Monacelli Press. OL 22741487M.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Gregory; Massengale, John Montague (1983). New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism, 1890–1915. New York: Rizzoli. OCLC 9829395.

- Waters, Theodore (October 1903). "A Triumph for the New Art". Everybody's Magazine. Vol. 9. Ridgeway Company.

External links

- Official website

- New Amsterdam Theatre at the Internet Broadway Database

- "Images related to New Amsterdam Theatre". NYPL Digital Gallery.