New York Stock Exchange Building

New York Stock Exchange | |

New York City Landmark No. 1529 | |

Classical Revival architecture | |

| Part of | Wall Street Historic District (ID07000063) |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 78001877 |

| NYSRHP No. | 06101.000373 |

| NYCL No. | 1529 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 2, 1978[3] |

| Designated NHL | June 2, 1978[3] |

| Designated NYSRHP | June 23, 1980[1] |

| Designated NYCL | July 9, 1985[2] |

The New York Stock Exchange Building (also the NYSE Building), in the

The marble

The NYSE had occupied the site on Broad Street since 1865 but had to expand its previous building several times. The structure at 18 Broad Street was erected between 1901 and 1903. Within two decades, the NYSE's new building had become overcrowded, and the annex at 11 Wall Street was added between 1920 and 1922. Three additional trading floors were added in the late 20th century to accommodate increasing demand, and there were several proposals to move the NYSE elsewhere during that time. With the growing popularity of electronic trading in the 2000s, the three newer trading floors were closed in 2007.

The building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1978 and designated a city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1985. The building is also a contributing property to the Wall Street Historic District, a National Register of Historic Places district created in 2007.

Site

The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) Building is in the

A security zone created after the September 11 attacks surrounds the NYSE Building. In addition, a

Architecture

The building houses the

Facade

18 Broad Street

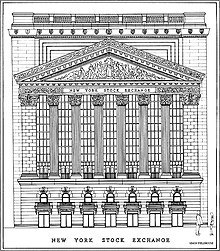

18 Broad Street, the older structure in the modern building, is at the center of the block. The structure has a

The original structure contains colonnades along both Broad and New Streets.[26][27][28] Unlike the Roman sources from which the design of 18 Broad Street's facade is derived, the building has entrances at basement level on both sides, rather than grand staircases leading to the colonnades.[25] On Broad Street is a two-story podium made of granite blocks. It is divided vertically into seven bays of doorways at the basement, which on Broad Street is at ground level. There are arched windows with balconies on the first story.[24][26] A decorative lintel tops each of the basement openings, while brackets support each short balcony.[29] South of the podium is a two-bay-wide extension with a double-height arch at basement level, providing access to the offices near the trading floor.[30] On New Street, rusticated marble blocks clad the basement and first stories, and the openings are simpler in design compared to the Broad Street facade.[31]

Above the podiums on Broad and New Streets, the colonnades span the second through fifth stories. Both colonnades consist of two flat

Above the colonnade on Broad Street is a triangular pediment, originally carved by the Piccirilli Brothers[37] and designed by John Quincy Adams Ward and Paul Wayland Bartlett.[26][38][39] The pediment measures about 100 feet (30 m) above the sidewalk and about 110 feet (34 m) wide.[40] It is composed of eleven figures representing commerce and industry.[22] The central figure is a female representation of integrity, flanked by four pairs of figures depicting planning/building, exploring/mining, science/industry, and agriculture.[33][41][42] Two small children, also described as putti,[41] sit at Integrity's feet.[34][41] The figures were originally fashioned in marble from 1908 to 1909;[34] they were replaced in 1936 with sheet metal carvings coated with lead.[22][43][44]

A

11 Wall Street

The northern annex at 11 Wall Street is 22 stories tall, or 23, including the ground-level basement on Broad Street, and is constructed of Georgia marble.[18][17][45] It occupies an irregular lot extending 58 feet (18 m) on Broad Street, 156 feet (48 m) on Wall Street, and 100 feet (30 m) on New Street.[46][47] 11 Wall Street has an overall height of 258 feet (79 m).[45] The building's massing, or general form, incorporates setbacks at the ninth, nineteenth, and twentieth stories, as well as a roof above the twenty-second story. A heavy cornice runs above the eighteenth story.[18]

The annex's main entrance is a chamfered corner at Wall and New Streets. It consists of a rectangular doorway with Doric columns on each side, above which are a transom, entablature, and balustrade. The windows on 11 Wall Street are largely paired rectangular sash windows.[48] The annex contains design elements that visually connect it to the older building. On Broad Street, a belt course above the first story, two floors above street level, connects with the top of the podium on 18 Broad Street. The balustrade at the ninth story, ten floors above street level, connects with those atop 18 Broad Street.[18] Additionally, on the Wall Street facade, there is a small row of Corinthian pilasters flanking the second- through fifth-story windows. These pilasters are similar in design to the colonnades of 18 Broad Street.[18][49]

Interior

The exchange is the locus for a large amount of technology and data. When the building was first completed, pneumatic tubes and telephones were installed on the trading floor and other parts of the building to facilitate communications.[50][51] Some 25,000 feet (7,600 m) of pipes were used to heat and cool the offices. Four boilers generated a combined 800 horsepower (600 kW) of steam, while three power generators were capable of a combined 1,040 horsepower (780 kW).[23] In addition, numerous elevators were constructed in the building's constituent structures. Six passenger elevators, three lifts, and five dumbwaiters were provided at 18 Broad Street.[52] Eleven elevators were installed at 11 Wall Street.[46] A 2001 article noted that the trading floor required 3,500 kilowatts (4,700 hp) of electricity, 8,000 phone circuits on the trading floor alone, and 200 miles (320 km) of fiber-optic cables below ground.[53]

Basement

There are four basement levels.[54] The machinery, electric and steam plants, maintenance workers' rooms, and vaults are in the basement and subbasement underneath the first-story trading floor.[21][55] The building was constructed with a steel safe deposit vault measuring about 118.58 feet (36 m) wide, 21 feet (6 m) long, and 9 feet 10 inches (3 m) high, weighing 776 short tons (693 long tons; 704 t) when empty.[23][55] A basement corridor led to the Wall Street station of the city's first subway line (now the 4 and 5 trains), under Broadway.[56]

The lowest basement level is 42 feet (13 m) below Wall Street. The basement is surrounded by a concrete cofferdam resting on solid rock.[52][55][57] The surrounding area had an atypically high water table, with groundwater being present a few feet below ground, partially because Broad Street was the former site of a drainage ditch.[58] As a result, caissons were used to excavate part of the 18 Broad Street site, and the remainder of the basement and subbasements were then excavated.[57][58] The caissons were built of wood and measured 30 by 8 by 50 feet (9 m × 2 m × 15 m) each.[57]

Trading floors

The main trading floor (formerly the boardroom) on the first story at 18 Broad Street covers 15,000 square feet (1,400 m2).[50][59] The room extends the width of the block between New and Broad Streets.[24][28][a] The trading floor was laid out to maximize usable space and, as a result, had minimal space for visitors on the floor itself.[50][61] There was originally a narrow gallery for smokers on the New Street side and an admission area for guests on Broad Street.[56][62][63]

The room's floor is at the same level as New and Wall Streets; as built, a marble double stair from the basement at Broad Street provided an entrance for members.[20][21] The floor surface was originally covered with wood.[64] Interrupting the main trading floor are eight iron columns, the placement of which was decided after twenty to thirty drawings.[21] The lowest 20 feet (6.1 m) of the walls are clad in marble, with arched alcoves for access to other rooms.[21] The marble panels contain bluish-brownstone centers and pink-marble metopes at the top. Four transverse trusses spanning the width of the room, measuring 115 feet (35 m) long and 15 feet (4.6 m) thick, support the ceiling.[54][65] These trusses are carried on pairs of pilasters at each end and subdivide the ceiling into coffers.[21][65][66] The center of the ceiling is fitted with a 30-by-30-foot (9.1 by 9.1 m) skylight,[42][64] while the rest of the ceiling was gilded upon the building's completion.[65][67]

As constructed, there were 500 telephones in the room, as well as annunciators clustered around the New Street end and surrounding the large columns on the floor.[35][64] The northern and southern walls originally had colored "checkerboards" with over 1,200 panels, which could be lit in a variety of patterns to flash messages to members on the floor.[23][68][69] Each of the four primary trading areas contain the NYSE's opening and closing bells (originally just one bell), which are rung to mark the beginning and the end of each trading day.[70][71] Abutting the trading floor, but on higher levels, were doctors' rooms, baths, and barbershops for NYSE members.[42][55][56] A passageway leads north to the other trading floors at 11 Wall Street; another passage once led south to 20 Broad Street.[54]

There is another trading floor at the northeast section of 11 Wall Street, nicknamed "the Garage".

Upper stories

Post included a large interior light shaft on 18 Broad Street's upper stories as part of the building's design. The location of this shaft, and that of the trading floor, is affected by the planning of the various rooms in the upper stories.[21] On the sixth story, above the trading floor, is the boardroom (formerly the Bond Room). This room has a skylight and coffered ceiling. The walls are adorned with white and gold decorations and contain arches supported by flat pilasters.[42][55] While the room was originally outfitted with semicircular tiers surrounding a dais,[55] these have since been removed.[54]

The seventh story of 18 Broad Street contained the Luncheon Club facing New Street, which covered 12,055 square feet (1,119.9 m2). The Luncheon Club's main dining room measured 76 by 40 feet (23 by 12 m), with an 18-foot (5.5 m) high ceiling.[23][72] A smaller dining room was provided for non-smokers, separated from the main dining room by a lounge. The eighth story along New Street contained the club kitchen with a mezzanine-level serving gallery.[72] After the Luncheon Club shut down in 2006,[73] the room was converted into an event space called Freedom Hall.[74]

The other rooms on the sixth story of 18 Broad Street included the Governor's Room on the Wall Street side, as well as the president's and secretary's rooms, committee rooms, and offices on the New Street side.[24] The Committee on Arrangements and Admission room featured two large brass chandeliers. The other committee rooms on this story were similarly ornate.[55] The seventh and eighth stories facing Broad Street contained committee rooms and offices.[75] There are also offices on the upper floors at 11 Wall Street.[54] Up to the 17th floor, a typical floor at 11 Wall Street contains 7,500 square feet (700 m2) of space, but each of the top six floors spans 3,661 square feet (340.1 m2) on average.[46] The upper stories of both structures contain several event spaces.[74]

History

Goods had been traded on Wall Street as early as 1725.[76] Auctioneers had intermediated securities exchanges until 1792, brokers signed the Buttonwood Agreement to form an organization for securities trading, which later became the NYSE.[77][2] In 1817, the organization re-formed as the New York Stock and Exchange Board. The broker organization began renting out space exclusively for securities trading, using several locations for the next half-century, including the Tontine Coffee House.[78] Ten years later, the organization moved into the Merchants' Exchange at 55 Wall Street.[76][79] Rapid growth in securities trading during the latter half of the nineteenth century was reflected in the growth of the Stock and Exchange Board.[80][81]

Previous structure

In December 1865, the Stock and Exchange Board moved to 10 Broad Street, between Wall Street and Exchange Place.[24][78][82] The New York Stock Exchange Building Company owned the structure and the Exchange itself used a second-story room.[82] The board's membership nearly doubled from 583 to 1,060 when it acquired the Open Board of Stock Brokers in 1869.[83][84] The Stock and Exchange Board, originally a minor shareholder in the Building Company, bought all the company's stock in November 1870.[85][86] The company acquired the lot at 12 Broad Street, and the two buildings were combined and expanded to designs by James Renwick Jr. The Stock Exchange Building reopened in September 1871.[85][87] Within eight years, even the expansion was insufficient for the overcrowded NYSE. The exchange's governing committee thus purchased additional land on Broad and New Streets in late 1879.[88] Renwick was hired for another extension of the previous Stock Exchange Building, which was completed in 1881.[88][89] The expanded quarters provided better ventilation and lighting, as well as a larger board room.[89]

By 1885, the city's sanitary engineers described the plumbing and ventilation as inadequate.[90] The board room, nearer New Street, was expanded yet again in 1887 toward Broad Street.[91] An 1891 guidebook characterized the Stock Exchange Building as a five-story French Renaissance marble structure, with a spur toward Wall Street, adjoining the Mortimer Building to the northeast. Even though the building sat largely on Broad and New Streets, it had become more closely associated with Wall Street.[92] The building was largely shaped like a letter "T" and had a much longer frontage on New Street than on Broad Street. By the end of the 1890s, the structure was again overcrowded.[93]

Replacement

Planning and construction

The NYSE acquired the plots at 16–18 Broad Street in late 1898[94][95] after two years of negotiation.[96] The NYSE was planning yet another expansion to its building, which started in 1903 after the plots' existing lease expired.[96] The following January, the NYSE acquired the lot on 8 Broad Street.[93][97] The land cost $1.25 million in total (equivalent to $37.64 million in 2023).[98]

Eight architects were invited to participate in an architectural design competition for a replacement building on the site.[42] This competition involved a brief by architects William Ware and Charles W. Clinton.[83][99][100] The foremost consideration was that the trading floor had to be an open space with few to no interruptions. The NYSE solicited proposals for a structure that had banking space on the ground floor, as well as proposals with no such space.[83] The plans had to consider the lot's complex topography, unusual shape, underlying ground, and the removal of the large deposit vault.[101] Publicist Ivy Lee wrote that the structure was to "be both monumental architecturally and equipped with every device that mechanics, electricity or ingenuity could supply with every resource needed to transact the security trading for the commercial center of the world".[99][102] The NYSE governors ultimately decided against including a ground-level banking room, which they felt would restrict movement during emergencies.[66][83]

In December 1899, the NYSE's governing committee unanimously approved the submission by George B. Post.[103][104] That month, a committee was formed to oversee the construction of the new building.[105] Post continued to revise his design during the next year.[98] By July 1900, the NYSE had arranged to move to the New York Produce Exchange at Bowling Green while the replacement NYSE Building was being constructed.[98][106] Post filed plans for the building with the New York City Department of Buildings on April 19, 1901.[107] Eight days later, the traders stopped working at the old building.[55][108] The cornerstone was laid on September 9, 1901.[100][109] The contractors excavating the site had to work around the old vault, which not only had to be preserved while the new vault and foundations were being built, but had to be delicately demolished afterward.[52][57]

Initially, the contractors had planned for the new structure to be completed within one year of the old building's closure. Various issues delayed the opening by one year, including difficulty in demolishing the old building, as well as alterations made to the original plan during construction.[52] R. H. Thomas, a chairman of the committee that oversaw construction, justified the delay by saying, "Where so many of our members spend the active years of their lives, they are entitled to the best that architectural ingenuity and engineering skill can produce."[42] Over two thousand guests attended the building's dedication ceremony on April 22, 1903. The event included speeches from Rudolph Keppler, the president of the New York Stock Exchange, and Seth Low, the mayor of New York City.[23][110] The trading floor opened for business the following day. The New York Times reported, "When the gavel fell many brokers vied with each other for the honor of making the first business transaction."[111]

Early years and annex

In the years after the NYSE Building's completion, the exchange encountered difficulties, including the

In its first two decades, and especially following the end of World War I, the NYSE grew significantly. The rebuilt 18 Broad Street quarters quickly became insufficient for the exchange's needs.[112] In December 1918, the NYSE bought the Mortimer Building northeast of its existing structure, giving the exchange an additional 3,220 square feet (299 m2). The annex would give the building a full frontage on Wall Street, whereas previously 18 Broad Street only ran along Wall Street for 15 feet (4.6 m).[120][121] The Mortimer Building's demolition commenced in mid-1919.[122] The NYSE also leased the Wilks Building northwest of its existing structure in January 1920;[49] the lot was assessed at $1.9 million (equivalent to $21.9 million in 2023).[123] Demolition of the Wilks Building began in June 1920.[123]

Trowbridge and Livingston received the commission to design an annex on the Mortimer and Wilks sites, while Marc Eidlitz and Son received the contract for the construction of the annex.[122] Plans for an annex at 11 Wall Street, reaching twenty-two stories above a basement, were finalized in February 1920. The NYSE would lease the first eight stories and the basement, including several stories for an expanded trading floor known as the "Garage", while the upper stories would be leased to office tenants.[49][124] By August 1922, the annex was nearly complete, and several firms had already signed leases for about 60 percent of the available office space.[46][47] The annex's trading floor opened during the last week of December 1922.[125]

Later operations and expansions

1920s to 1940s

The office annex was insufficient to accommodate the long-term growth of the NYSE. In mid-1926, the exchange leased three floors at the neighboring Commercial Cable Building on 20 Broad Street. The ground floor was planned to be connected to that of 18 Broad Street, while the first and second floors of that building would be combined into a single bond trading room with a high ceiling. These stories were internally connected to 18 Broad Street, although they remained separate buildings.[126][127] In 1928, the NYSE bought not only the Commercial Cable Building but also the Blair Building, taking control of all the property on the city block.[128][129]

The NYSE's growth stopped suddenly with the

1950s to 1980s

By 1954, the NYSE was planning to replace the building at 20 Broad Street with a skyscraper, a portion of which would contain auxiliary facilities for the NYSE. The exchange formally held an option to expand its trading floor to 20 Broad Street if the need arose.

By the early 1960s, the NYSE needed to expand its operations again and was considering moving out of its main building entirely. Previously, the structure had housed some securities firms that were also members of the exchange, but the NYSE needed the space for itself, and the last firm moved out during late 1961.[140] At that time, the NYSE's leadership hoped to acquire land in Lower Manhattan and construct a new building within five years.[141] The NYSE made several proposals for new headquarters, none of which were carried out.[17][b] The exchange selected a site in Battery Park City in 1965 but dropped plans for the site the next year.[142][143][144] The NYSE's governors voted in 1967 to expand the trading floor into 20 Broad Street.[145] The expansion, nicknamed the "Blue Room",[42] opened in July 1969. It provided 8,000 square feet (740 m2) of additional space to the 23,000-square-foot (2,100 m2) trading floor, which could accommodate almost two hundred more clerks.[146] In addition, some of the computer facilities were moved to Paramus, New Jersey, between 1967 and 1969.[147]

The NYSE looked to build a new headquarters along the

1990s to present

The NYSE, AMEX, and J.P. Morgan & Co. proposed the creation of a financial "supercenter" on the block immediately east of the NYSE Building, across Broad Street, in 1992.[155] The supercenter, to be developed by Olympia and York and designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), would have consisted of a 50-story tower above two 50,000-square-foot (4,600 m2) trading floors. After Olympia and York severed their involvement because of financial difficulties, and team composed of J.P. Morgan & Co., Lewis Rudin, Gerald D. Hines, and Fred Wilpon took over the project. The NYSE withdrew from the supercenter in 1993.[149]

The NYSE resumed its search for alternate sites for its headquarters in mid-1996. During the previous five years, over a thousand companies had been listed on the exchange's board, and trading volume had more than doubled.

As an interim measure, the NYSE looked into opening a trading floor at 30 Broad Street less than a block to the south in 1988.[168] The expansion, which opened in late 2000,[169] consisted of a 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) facility designed by SOM.[170][171] The same year, the NYSE and the city and state governments of New York agreed to acquire the block to the east.[170][172] The plan included demolishing all structures except for 23 Wall Street to make way for a 50-story skyscraper designed by SOM.[170][173] The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks resulted in only the third multi-day closure of the NYSE's trading floor in the building's history.[132][174] The Lower Manhattan expansion was ultimately canceled in 2002 because the NYSE wanted to build a trading floor elsewhere, which would allow the exchange to continue operating even if terrorists targeted the main building.[175]

Over the following years, the increase in electronic trading made physical trading space redundant.[176][177] The floor accounted for fewer than half of trades in 2007, down from 80 percent in 2004.[178] As a result, the 30 Broad Street trading floor closed in February 2007.[42][178] The Blue Room and Extended Blue Room were announced for closure later that year, leaving only the main floor and the Garage.[178][179] The NYSE Building's trading floor was closed for two months in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City, but electronic trading continued throughout.[180]

Impact

Critical reception

When the 18 Broad Street building was completed, publicist Ivy Lee wrote: "In outer contour it suggests the columnar, monumental architecture of the ancient Greeks. But this exterior shelters the very essence of the strenuous energy of this twentieth century."[181] Percy C. Stuart of Architectural Record said in 1901: "It will be the first great commercial edifice to be built in New York in the twentieth century, a fitting precursor of an age destined for great buildings."[34][182] Architectural critic Montgomery Schuyler appraised the building as a "very brilliant and successful piece of work".[183] Schuyler especially appreciated that the colonnades' columns visually divided the large windows behind them;[32][39] his only negative criticism was that the carving of the basement was incongruous with the rest of the design.[184]

After the annex was completed, the Downtown League declared it to be the "best building" erected in Lower Manhattan in 1922.[185] Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis said in 2021: "The massive building imbued the NYSE with authority, reflecting its view of itself and its role in the economy" while also providing space for a trading floor.[76]

Some commentary focused on specific parts of the design. Stuart of Architectural Record wrote that, with the colonnades and large trading-floor windows, "the new Exchange will have a scale of its own, at once so simple and impressive as to readily signalize it among its surroundings".[186] Conversely, Scribner's Magazine wrote in 1903 that the pediment on Broad Street was disadvantaged by its location opposite several tall buildings, "which has caused Ward to give to his figures very great scale and to diminish their number".[40] An Architectural Record article the following year pointed out a similar issue, stating that a front view was extremely difficult unless one entered a nearby building, and that "neither architect nor sculptor could have expected many persons to examine the building in that way".[187] Architectural writer Robert A. M. Stern said that the pediment's sculptures gave the building "an air of magisterial calm as it presided over the financial world's most important intersection".[66]

Cultural impact

The NYSE's logo, on which the NYSE holds a trademark, depicts the columns on the 18 Broad Street building.[188] This has led to disputes when coupled with the building's status as an icon of the NYSE. For instance, in 1999, the NYSE unsuccessfully sued the New York-New York Hotel and Casino for trademark infringement after the hotel's developers built the "New York-New York $lot Exchange", loosely based on 18 Broad Street.[188][189][190]

The NYSE Building's prominence has also made it the location of artworks. In 1989, artist Arturo Di Modica installed his sculpture Charging Bull in front of the building, in an act of guerrilla art.[191] The sculpture was removed within a day and ultimately reinstalled at Bowling Green, two blocks south.[192] Subsequently, in 2018, Kristen Visbal's bronze sculpture Fearless Girl was installed outside the NYSE Building on Broad Street.[193] The Fearless Girl sculpture was originally installed in 2017 facing Charging Bull at Bowling Green, but it was moved to the NYSE because of complaints from Di Modica.[194]

Landmark designations

As early as 1965, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) had considered designating the 18 Broad Street building, but not the 11 Wall Street annex, as a landmark.[2][195] It was one of the first buildings the LPC had proposed for landmark status, as the commission had just gained the authority to designate the city's structures as landmarks.[195] At the time, the NYSE and several private owners opposed landmark status for their respective buildings, since any proposed modification to a landmark would require a cumbersome review by the city government.[196] The LPC hosted a second landmark hearing in 1980 but again declined to designate the building.[2] In 1983, The New York Times cited the NYSE Building as one of several prominent structures that had not been designated by the LPC in the agency's first eighteen years, alongside Rockefeller Center and the Woolworth Building.[197] The LPC reconsidered designation for 18 Broad Street in 1985.[198] After numerous public hearings, the LPC finally granted landmark status to 18 Broad Street on July 9, 1985,[2][199] as landmark number 1529.[2]

Both 18 Broad Street and 11 Wall Street were added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) as a National Historic Landmark on June 2, 1978.[3][200][201] The building was designated as a contributing property to the Wall Street Historic District,[202] a National Register of Historic Places district, in 2007.[203]

See also

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York City

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan below 14th Street

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan below 14th Street

References

Notes

- ^ The NYSE, New-York Tribune, and Emporis all give floor dimensions of 109 by 140 feet (33 by 43 m), with a ceiling 72 feet (22 m) high.[23][42][60] Architectural Record, the New-York Tribune, and Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis give a width of 138 feet (42 m), a length of 112 feet (34 m), and a height of 80 feet (24 m).[28][56][34] Architects' and Builders' Magazine gives a width of 144 feet (44 m), a length of 109 feet (33 m), and a height of 74.5 feet (22.7 m).[24]

- ^ Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) and Richard W. Adler proposed new NYSE buildings at the first World Trade Center in 1960–1961. O'Connor & Kilham and I. M. Pei made proposals in 1963, and SOM's Gordon Bunshaft made a proposal in 1966.[17]

Citations

- ^ "Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS)". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. November 7, 2014. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Stargard & Pearson 1985, p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Federal Register: 44 Fed. Reg. 7107 (Feb. 6, 1979)" (PDF). Library of Congress. February 6, 1979. p. 7538 (PDF p. 338). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Archivedfrom the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "11 Wall Street, 10005". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- ^ "MTA Neighborhood Maps: Lower Manhattan" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ a b "Transit & Bus Committee Meeting" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 22, 2019. p. 218. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Tribeca Trib Online. Archivedfrom the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Walker, Ameena (May 14, 2018). "Tourist-heavy Wall Street could get pedestrian-friendly improvements". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Morris, Sebastian (February 28, 2020). "LPC to Review Proposal for Revamped Pedestrian Space in Financial District". New York YIMBY. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Glassman, Carl (December 16, 2019). "Seats Beside 'Fearless Girl' to Be First Small Step in Future Streetscape Redo". Tribeca Trib Online. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ Botros, Alena (May 5, 2023). "What is the New York Stock Exchange?". Fortune. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ^ a b c d Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 257.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 1978, p. 5.

- ^ Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, p. 460.

- ^ a b c Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1903, p. 390.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stuart 1901, p. 541.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service 1978, p. 2.

- ^ ProQuest 571399564.

- ^ a b c d e f Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1903, p. 389.

- ^ a b Macaulay-Lewis 2021, pp. 71, 73.

- ^ a b c d e Stargard & Pearson 1985, p. 5; National Park Service 1978, p. 2.

- ^ a b Lee 1902, pp. 2773–2774.

- ^ a b c d e Stuart 1901, p. 537.

- ^ a b c Stargard & Pearson 1985, p. 5; National Park Service 1978, p. 5.

- ^ a b Stargard & Pearson 1985, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Stargard & Pearson 1985, p. 6.

- ^ a b Schuyler 1902, p. 417.

- ^ a b c Stargard & Pearson 1985, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f Macaulay-Lewis 2021, p. 73.

- ^ a b Lee 1902, p. 2774.

- ^ Stuart 1901, pp. 537–539.

- from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Scribner's Magazine 1904, pp. 381–382.

- ^ a b Stargard & Pearson 1985, p. 4.

- ^ a b Scribner's Magazine 1904, p. 382.

- ^ a b c Scribner's Magazine 1904, p. 384.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The Building". New York Stock Exchange. Archived from the original on May 14, 2007. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 128844512.

- ^ from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "11 Wall Street – The Skyscraper Center". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. April 7, 2016. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 129995555.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ National Park Service 1978, pp. 5–6.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c Lee 1902, p. 2775.

- ^ Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1903, pp. 394–395.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 1978, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1903, p. 396.

- ^ a b c d "The New Stock Exchange: Most Expensive and Most Elaborately Equipped Business Structure in the World". New-York Tribune. November 30, 1902. pp. 31, 32. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d "For the New Exchange". New-York Tribune. July 7, 1901. pp. 27, 28. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Stuart 1901, pp. 530–531.

- ^ Stuart 1901, p. 532.

- ^ "New York Stock Exchange". Emporis. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ Stuart 1901, pp. 532–534.

- ^ Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1903, pp. 391–392.

- ^ Stuart 1901, pp. 546–547.

- ^ a b c Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1903, pp. 392–393.

- ^ a b c Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1903, p. 391.

- ^ a b c Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, p. 189.

- ^ Stuart 1901, p. 547.

- ^ Lee 1902, pp. 2774–2775.

- ^ Stuart 1901, pp. 543, 546.

- from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "The NYSE Bell". New York Stock Exchange. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1903, pp. 395–396.

- from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ a b "NYSE Events". New York Stock Exchange. May 11, 2005. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1903, pp. 389–390.

- ^ a b c Macaulay-Lewis 2021, p. 71.

- ^ National Park Service 1978, p. 7.

- ^ a b Stargard & Pearson 1985, pp. 1–2; National Park Service 1978, pp. 8–9; Stuart 1901, p. 527.

- ^ The Picture of New-York 1828, pp. 207–208.

- ^ National Park Service 1978, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Stargard & Pearson 1985, p. 2.

- ^ a b Eames 1894, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d Stuart 1901, p. 529.

- ^ Eames 1894, p. 52.

- ^ a b Eames 1894, p. 57.

- (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ a b Eames 1894, p. 62.

- ^ ProQuest 940505200.

- (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Eames 1894, p. 65.

- ^ Kobbe 1891, pp. 98–99.

- ^ ProQuest 574551758.

- (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ "The Private Sales Market". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 62, no. 1603. December 3, 1898. p. 821 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ ProQuest 574542063.

- ^ "Real Estate Market". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 63, no. 1610. January 21, 1899. p. 101 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ ProQuest 570868098.

- ^ a b Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, p. 187.

- ^ a b Stargard & Pearson 1985, p. 3.

- ^ Stuart 1901, p. 530.

- ^ Lee 1902, p. 2773.

- (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ProQuest 570866652.

- ProQuest 574694404.

- (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ "New Stock Exchange Building". Yonkers Statesman. April 20, 1901. p. 3. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 570975213.

- ProQuest 128795354.

- (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Stargard & Pearson 1985, p. 5; National Park Service 1978, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Markham 2002, p. 34.

- ^ National Park Service 1978, p. 11.

- ^ "The exchange opens". The Independent. December 7, 1914. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ from the original on December 13, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ Postal, Matthew (June 26, 2012). "New York Curb Exchange (incorporating the New York Curb Market Building), later known as the American Stock Exchange" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. pp. 2–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ProQuest 129679046.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ProQuest 576192605.

- The Sun and the Erie County Independent. December 28, 1922. p. 2. Archivedfrom the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ProQuest 130338573.

- ProQuest 130501731.

- ProQuest 1113509574.

- ISSN 0730-2355.

- ^ Stargard & Pearson 1985, p. 5; National Park Service 1978, p. 11.

- ^ a b "No U.S. trading Thursday". CNN. September 12, 2001. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ Stargard & Pearson 1985, p. 3; National Park Service 1978, p. 12.

- ^ "Timeline". New York Stock Exchange. August 15, 2010. Archived from the original on August 15, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ProQuest 1318407727.

- from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- OL 1130718M.

- ProQuest 1323999237.

- ProQuest 1327441396.

- ProQuest 132644420.

- ProQuest 132632360.

- ProQuest 133034575.

- from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ProQuest 133133872.

- ProQuest 133259615.

- ProQuest 550190301.

- ProQuest 133206757.

- ProQuest 147944126.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 258.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ProQuest 397922932.

- ProQuest 308243730.

- ^ from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, pp. 258–259.

- from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 259.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Knox, Noelle; Moor, Martha T. (October 24, 2001). "'Wall Street' migrates to Midtown". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ProQuest 1441169097.

- ^ Grant, Peter (October 29, 1996). "Hard sell for NYSE plan". New York Daily News. p. 238. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 249306315.

- ProQuest 191144118.

- ProQuest 209750136.

- ^ a b c Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 260.

- ^ "New York Stock Exchange Trading Floor Expansion". New York Construction News. Vol. 49. December 2000. p. 25.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- from the original on September 8, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ProQuest 398975237.

- ^ from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ProQuest 399097281.

- ^ Aratani, Lauren (May 26, 2020). "New York Stock Exchange reopens two months after closing due to Covid-19". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Lee 1902, p. 2772.

- ^ Stuart 1901, pp. 526–527.

- ^ Schuyler 1902, p. 420.

- ^ Schuyler 1902, pp. 419–420.

- ProQuest 130090858.

- ^ Stuart 1901, p. 551.

- ^ Architectural Record 1904, p. 465.

- ^ a b "New York Stock Exchange Inc v. New York New York Hotel LLC LCC". Findlaw. April 1, 2002. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- from the original on March 31, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Moyer, Liz (November 28, 2018). "'Fearless Girl' on the move, but leaves footprints for visitors to stand in her place". CNBC. Archived from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- CNNMoney. Archivedfrom the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Hanson, Kitty (October 18, 1965). "Help! Landmarks Group Issues Civic SOC". New York Daily News. p. 474. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Fight City OK on Landmarks". New York Daily News. November 7, 1965. p. 1086. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Shepard, Joan (March 15, 1985). "Landmark Designation for B. Altman". New York Daily News. p. 1272. Retrieved December 3, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on November 12, 2019. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ United States Department of the Interior (1985). "Catalogue of National Historic Landmarks". U.S. Department of the Interior. p. 162. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ "Wall Street Historic District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. February 20, 2007. pp. 4–5. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places 2007 Weekly Lists" (PDF). National Park Service. 2007. p. 65. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

Sources

- Eames, F.L. (1894). The New York Stock Exchange. T. G. Hall. Archived from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Facade of the New York Stock Exchange" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 16. November 1904.

- Kobbe, Gustav (1891). New York and Its Environs. Harper & Brothers. Archived from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- Lee, Ivy (November 1902). "The New Centre of American Finance". The World's Work. Vol. 5. pp. 2772–2775.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Macaulay-Lewis, Elizabeth (2021). Antiquity in Gotham: The Ancient Architecture of New York City. Fordham University Press. OCLC 1176326519. Archivedfrom the original on April 2, 2023. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- Markham, J.W. (2002). A Financial History of the United States: From Christopher Columbus to the Robber Barons (1492–1900). ISBN 978-0-7656-0730-0.

- New York Stock Exchange (Report). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 2, 1978. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- "The New York Stock Exchange, George B. Post, Architect". Architects' and Builders' Magazine. Vol. 35. June 1903. pp. 389–396.

- "The Pediment of the New York Stock Exchange". Scribner's Magazine. Vol. 36. 1904.

- The Picture of New-York, and Stranger's Guide to the Commercial Metropolis of the United States. A. T. Goodrich. 1828. pp. 206–207. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- Schuyler, Montgomery (September 1902). "The New York Stock Exchange" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 12. pp. 419–420.

- Stargard, William; Pearson, Marjorie (July 9, 1985). New York Stock Exchange Building (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Gregory; Massengale, John Montague (1983). New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism, 1890–1915. Rizzoli. OCLC 9829395.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2006). New York 2000: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Bicentennial and the Millennium. Monacelli Press. OL 22741487M.

- Stuart, Percy C. (July 1901). "The New York Stock Exchange" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 11. pp. 526–552.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

External links

- New York Stock Exchange website

- George R. Adams (March 1977). "New York Stock Exchange National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination". National Park Service. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination". National Park Service. 1983.