Ngo Dinh Diem presidential visit to Australia

| ||

|---|---|---|

Prime Minister of the

State of Vietnam (1954–1955) President of South Vietnam (1955–1963)Policies and theories

Major events

Elections

Diplomatic activities

Family

|

||

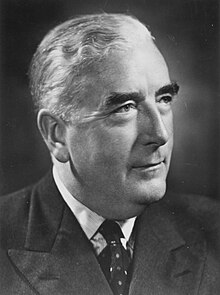

The Ngô Đình Diệm presidential visit to Australia from 2 to 9 September 1957 was an official visit by the first president of the

Diệm addressed the

Diệm's visit was a highmark in relations between Australia and South Vietnam. Over time, Diệm became unpopular with his foreign allies, who began to criticise his autocratic style and religious bias. By the time of his

Background

In 1933, the devoutly Catholic Diệm was appointed Interior Minister of Vietnam, serving under Emperor

In 1954, the French lost the

Meetings and ceremonies

Diệm arrived in the capital

Diệm travelled with five others, including the Minister for Public Works and Communications, the Health Minister, and the Permanent Secretary-General of the Department for National Defense.[20] Ahead of his arrival, the South Vietnamese leader had specifically asked to visit Australian manufacturing sites in Sydney and Melbourne, particularly those in the food processing, textile, shipbuilding and housing industries.[20]

Upon disembarking from his plane at

The centrepiece of Diệm's visit was a speech to a joint sitting of the

On Wednesday, 4 September,

The guard of honour and a 21-gun salute that Diệm received at Parliament House was repeated in Sydney and Melbourne, where large crowds cheered Diệm's arrival at the airport and the passing of his motorcade.[1] After arriving in Sydney on Friday, September 6, around midday aboard the RAAF Convair,[27] the South Vietnamese leader was taken outside the capital cities for two days during the weekend,[20] so that he could see the Snowy Mountains Scheme, a large hydroelectricity project in highland Victoria.[22] He returned to Sydney on Sunday, September 8, and left Australia the following evening.[20] In one of Diệm's final functions in Sydney, a minor emergency occurred at the Australia Hotel during a banquet hosted by the Premier of New South Wales, Joseph Cahill. A fire ignited in a pile of rubbish, causing alarm bells to sound for ten minutes, interrupting Premier Cahill when he was making his speech, but no evacuation was required.[29]

At the end of the visit, Menzies bestowed on Diệm an honorary

Diệm spent little time on detailed defence and policy discussions with Australian officials during the trip, because of his extensive meetings with Catholic leaders.

Media reception and support

The Australian media wrote uniformly glowing reports that heaped praise on Diệm, and generally presented him as a courageous, selfless and wise leader.

The mainstream media depicted Diệm as a friendly and charismatic leader who related well to the populace.

The strongest support for Diệm came from the Australian Catholic media.

The

Diệm's achievements and support for Catholics were particularly praised by

Diệm's visit prompted increased interest in Vietnam by Australian Catholics, particularly supporters of the DLP. Australian Catholics came to see South Vietnam as an anti-communist and Vatican stronghold in Asia and as a result, became strong supporters of the Vietnam War.[46] Harold Lalor, a Jesuit priest and leading confidant of Santamaria,[47] had studied with Thục in Rome. During the trip, Diệm met with Gilroy,[31] the first Australian cardinal, as well as Santamaria and Archbishop of Melbourne Daniel Mannix, both of whom praised him strongly. Mannix was one of the most powerful men in Australia during the era, and had great political influence.[31]

Aftermath

The positive reception accorded to Diệm in 1957 contrasted with increasingly negative Australian attitudes towards Vietnam. Over time, the media in both Australia and the United States began to pay more attention to Diệm's autocratic style and religious bias,

See also

- Ngô Đình Diệm presidential visit to the United States

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Ham, p. 57.

- ^ a b Jacobs, pp. 100–104.

- ^ Jacobs, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Karnow, p. 231.

- ^ Jacobs, p. 22.

- ^ Jacobs, p. 23.

- ^ Jacobs, p. 25.

- ^ Jacobs, pp. 26–33.

- ^ Karnow, p. 233.

- ^ Jacobs, p. 37.

- ^ Jacobs, pp. 40–42.

- ^ Karnow, p. 235.

- ^ Jacobs, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Karnow, p. 234.

- ^ Jacobs, p. 85.

- ^ a b Karnow, p. 239.

- ^ Jacobs, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Edwards (1997), p. 24.

- ^ a b c Torney-Parlicki, p. 210.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Vietnam's Leader Here Today For State Visit". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 September 1957. p. 5.

- ^ a b c "President Ngo Dinh Diem in Canberra". The Age. 3 September 1957. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Edwards (1992), p. 194.

- ^ "Spiritual Rearmament Needed in Asia's Fight". The Age. 4 September 1957. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e Edwards (1992), p. 195.

- ^ "News of the Day". The Age. 5 September 1957. p. 2.

- ^ "Close Link Between Australia and Vietnam—President". The Age. 5 September 1957. p. 3.

- ^ a b "Crowded Day for Vietnam President". The Age. 6 September 1957. p. 5.

- ^ "Leader of Vietnam Sees Housing Areas". The Age. 7 September 1957. p. 5.

- ^ "President Diem Honorary Knight". The Sydney Morning Herald. 10 September 1957. p. 4.

- ^ a b c "Aust. to increase aid for Vietnam". The Sydney Morning Herald. 10 September 1957. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Duncan, p. 341.

- ^ a b c d e f Edwards (1992), p. 197.

- ^ Torney-Parlicki, p. 211.

- ^ "A welcome visitor from Saigon". The Age. 3 September 1957. p. 2.

- ^ a b Edwards (1992), pp. 195–197.

- ^ Jacobs, p. 95.

- ^ Tucker, pp. 288–293.

- ^ Edwards (1992), pp. 197–198.

- ^ Halberstam, p. 19.

- ^ Halberstam, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Jacobs, pp. 27–32.

- ^ Jacobs, pp. 86–88.

- ^ Jacobs, pp. 91–96.

- ^ Warner, p. 210.

- ^ Fall, p. 199.

- ^ Edwards (1997), p. 45.

- ^ Duncan, pp. 125, 170.

- ^ Jacobs, pp. 135–145.

- ^ Karnow, pp. 300–315.

- ^ Prochnau, pp. 309, 316–320.

- ^ Jones, p. 269.

- ^ Jacobs, p. 149.

- ^ Hammer, p. 145.

- ^ Karnow, pp. 318–325.

- ^ Karnow, pp. 323–330.

- ^ Edwards (1997), pp. 83–85.

- ^ Deery, Phillip. "Arthur's last hurrah: Calwell, Whitlam and the Ky visit to Australia". Australian Society for the Study of Labour History - Canberra Region. ASSLH. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ Edwards (1997), pp. 141–142.

- ^ Edwards (1997), pp. 143–146.

- ^ Edwards (1997), p. 290.

- ^ Edwards (1997), pp. 270–282.

- ^ Edwards (1997), pp. 314–316.

- ^ Edwards (1997), pp. 317–320, 325–326.

- ^ Edwards (1997), pp. 332–335.

- ^ Edwards (1997), p. 336.

- ^ Jupp, pp. 723–724, 732–733.

References

- Duncan, Bruce (2001). Crusade Or Conspiracy: Catholics and the Anti-Communist Struggle in Australia. UNSW Press. ISBN 0-86840-731-3.

- ISBN 1-86373-184-9.

- ISBN 1-86448-282-6.

- Fall, Bernard B. (1963). The Two Viet-Nams. Praeger.

- ISBN 978-0-7425-6007-9.

- ISBN 978-0-7322-8237-0.

- ISBN 0-525-24210-4.

- Jacobs, Seth (2006). Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diem and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-4447-8.

- Jones, Howard (2003). Death of a Generation: how the assassinations of Diem and JFK prolonged the Vietnam War. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505286-2.

- Jupp, James (2001). The Australian people: an encyclopedia of the nation, its people, and their origins. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80789-1.

- ISBN 0-670-84218-4.

- Torney-Parlicki, Prue (2000). Somewhere in Asia: War, Journalism and Australia's Neighbours 1941–75. ISBN 0-86840-530-2.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2000). Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War. Santa Barbara, California: ISBN 1-57607-040-9.

- Warner, Denis (1964). The Last Confucian: Vietnam, South-East Asia, and the West. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.