Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Bukharin | |

|---|---|

Николай Бухарин | |

12th Politburo | |

| In office 8 March 1919 – 2 June 1924 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin 9 October 1888 Moscow, Soviet Constitution of 1936 |

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series about |

| Imperialism studies |

|---|

|

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (Russian: Николай Иванович Бухарин, pronounced

Born in Moscow to two schoolteachers, Bukharin joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1906. In 1910, he was arrested by tsarist authorities, but in 1911 escaped and fled abroad, where he worked with fellow exiles Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky and authored works of theory such as Imperialism and World Economy (1915). After the February Revolution of 1917, Bukharin returned to Moscow, where he became a leading figure in the party, and after the October Revolution became editor of its paper, Pravda. He gained a high profile as a Left Communist, a position which included, in opposition to Lenin, a continuation of Russia's involvement in World War I. During the Russian Civil War, Bukharin wrote works including Economics of the Transition Period (1920) and The ABC of Communism (also 1920; with Yevgeni Preobrazhensky).

Bukharin was initially a proponent of

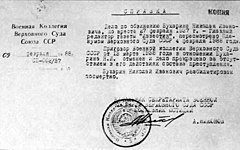

After a period in lower party positions, in 1934 Bukharin was reelected to the Central Committee and became editor of Izvestia. He became a principal architect of the 1936 Soviet constitution. In February 1937, during the Stalinist Great Purge, Bukharin was accused of treason and executed after a show trial in 1938.

Before 1917

Nikolai Bukharin was born on 27 September (9 October, new style), 1888, in Moscow.[1] He was the second son of two schoolteachers, Ivan Gavrilovich Bukharin and Liubov Ivanovna Bukharina.[1] According to Nikolai his father did not believe in God and often asked him to recite poetry for family friends as young as four years old.[2] His childhood is vividly recounted in his mostly autobiographic novel How It All Began.

Bukharin's political life began at the age of sixteen, with his lifelong friend

By age twenty, he was a member of the Moscow Committee of the party. The committee was widely infiltrated by the

In 1911, after a brief imprisonment, Bukharin was exiled to

In October 1916, while based in New York City, Bukharin edited the newspaper

From 1917 to 1923

At the news of the Russian Revolution of February 1917, exiled revolutionaries from around the world began to flock back to the homeland. Trotsky left New York on 27 March 1917, sailing for St. Petersburg.[5] Bukharin left New York in early April and returned to Russia by way of Japan (where he was temporarily detained by local police), arriving in Moscow in early May 1917.[4] Politically, the Bolsheviks in Moscow were a minority in relation to the Mensheviks and Social Democrats. As more people began to be attracted to Lenin's promise to bring peace by withdrawing from the Great War, [citation needed] membership in the Bolshevik faction began to increase dramatically – from 24,000 members in February 1917 to 200,000 members in October 1917.[6] Upon his return to Moscow, Bukharin resumed his seat on the Moscow City Committee and also became a member of the Moscow Regional Bureau of the party.[7]

To complicate matters further, the Bolsheviks themselves were divided into a right wing and a left wing. The right-wing of the Bolsheviks, including

While no one dominated revolutionary politics in Moscow during the October Revolution as Trotsky did in St. Petersburg, Bukharin certainly was the most prominent leader in Moscow.[10] During the October Revolution, Bukharin drafted, introduced, and defended the revolutionary decrees of the Moscow Soviet. Bukharin then represented the Moscow Soviet in their report to the revolutionary government in Petrograd.[11] Following the October Revolution, Bukharin became the editor of the party's newspaper, Pravda.[12]

Bukharin believed passionately in the promise of world revolution. In the Russian turmoil near the end of World War I, when a negotiated peace with the Central Powers was looming, he demanded a continuance of the war, fully expecting to incite all the foreign proletarian classes to arms.[13] Even as he was uncompromising toward Russia's battlefield enemies, he also rejected any fraternization with the capitalist Allied powers: he reportedly wept when he learned of official negotiations for assistance.[13] Bukharin emerged as the leader of the

After the ratification of the treaty, Bukharin resumed his responsibilities within the party. In March 1919, he became a member of the Comintern's executive committee and a candidate member of the

By 1921, he changed his position and accepted Lenin's emphasis on the survival and strengthening of the Soviet state as the bastion of the future world revolution. He became the foremost supporter of the New Economic Policy (NEP), to which he was to tie his political fortunes. Considered by the Left Communists as a retreat from socialist policies, the NEP reintroduced money and allowed private ownership and capitalistic practices in agriculture, retail trade, and light industry while the state retained control of heavy industry.

Power struggle

After Lenin's death in 1924, Bukharin became a full member of the Politburo.

Trotsky, the prime force behind the Left Opposition, was defeated by a triumvirate formed by Stalin, Zinoviev, and Kamenev, with the support of Bukharin. At the

Bukharin was worried by the prospect of Stalin's plan, which he feared would lead to "military-feudal exploitation" of the peasantry. Bukharin did want the Soviet Union to achieve industrialization but he preferred the more moderate approach of offering the peasants the opportunity to become prosperous, which would lead to greater grain production for sale abroad. Bukharin pressed his views throughout 1928 in meetings of the Politburo and at the Communist Party Congress, insisting that enforced grain requisition would be counterproductive, as War Communism had been a decade earlier.[19]

Fall from power

Bukharin's support for the continuation of the NEP was not popular with higher Party cadres, and his slogan to peasants, "Enrich yourselves!" and proposal to achieve socialism "at snail's pace" left him vulnerable to attacks first by Zinoviev and later by Stalin. Stalin attacked Bukharin's views, portraying them as capitalist deviations and declaring that the revolution would be at risk without a strong policy that encouraged rapid industrialization.

Having helped Stalin achieve unchecked power against the Left Opposition, Bukharin found himself easily outmaneuvered by Stalin. Yet Bukharin played to Stalin's strength by maintaining the appearance of unity within the Party leadership. Meanwhile, Stalin used his control of the Party machine to replace Bukharin's supporters in the Rightist power base in Moscow, trade unions, and the Comintern.

Bukharin attempted to gain support from earlier foes including Kamenev and Zinoviev who had fallen from power and held mid-level positions within the Communist party. The details of his meeting with Kamenev, to whom he confided that Stalin was "Genghis Khan" and changed policies to get rid of rivals, were leaked by the Trotskyist press and subjected him to accusations of factionalism. Jules Humbert-Droz, a former ally and friend of Bukharin,[15] wrote that in spring 1929, Bukharin told him that he had formed an alliance with Zinoviev and Kamenev, and that they were planning to use individual terror (assassination) to get rid of Stalin.[20] Eventually, Bukharin lost his position in the Comintern and the editorship of Pravda in April 1929, and he was expelled from the Politburo on 17 November of that year.[21]

Bukharin was forced to renounce his views under pressure. He wrote letters to Stalin pleading for forgiveness and rehabilitation, but through wiretaps of Bukharin's private conversations with Stalin's enemies, Stalin knew Bukharin's repentance was insincere.[22]

International supporters of Bukharin, Jay Lovestone of the Communist Party USA among them, were also expelled from the Comintern. They formed an international alliance to promote their views, calling it the International Communist Opposition, though it became better known as the Right Opposition, after a term used by the Trotskyist Left Opposition in the Soviet Union to refer to Bukharin and his supporters there.

Even after his fall, Bukharin still did some important work for the Party. For example, he helped write the 1936 Soviet constitution. Bukharin believed the constitution would guarantee real democratization. There is some evidence that Bukharin was thinking of evolution toward some kind of two-party or at least two-slate elections.[18] Boris Nikolaevsky reported that Bukharin said: "A second party is necessary. If there is only one electoral list, without opposition, that's equivalent to Nazism."[23] Grigory Tokaev, a Soviet defector and admirer of Bukharin, reported that: "Stalin aimed at one party dictatorship and complete centralisation. Bukharin envisaged several parties and even nationalist parties, and stood for the maximum of decentralisation."[24]

Friendship with Osip Mandelstam and Boris Pasternak

In the brief period of thaw in 1934–1936, Bukharin was politically rehabilitated and was made editor of Izvestia in 1934. There, he consistently highlighted the dangers of fascist regimes in Europe and the need for "proletarian humanism". One of his first decisions as editor was to invite Boris Pasternak to contribute to the newspaper and sit in on editorial meetings. Pasternak described Bukharin as "a wonderful, historically extraordinary man, but fate has not been kind to him."[25] They first met during the lying-in-state of the Soviet police chief, Vyacheslav Menzhinsky in May 1934, when Pasternak was seeking help for his fellow poet, Osip Mandelstam, who had been arrested – though at that time neither Pasternak nor Bukharin knew why.

Bukharin had acted as Mandelstam's political protector since 1922. According to Mandelstam's wife, Nadezhda, "M. owed him all the pleasant things in his life. His 1928 volume of poetry would never have come out without the active intervention of Bukharin. The journey to Armenia, our apartment and ration cards, contracts for future volumes – all this was arranged by Bukharin."[26] Bukharin wrote to Stalin, pleading clemency for Mandelstam, and appealed personally to the head of the NKVD, Genrikh Yagoda. It was Yagoda who told him about Mandelstam's Stalin Epigram, after which he refused to have any further contact with Nadezhda Mandelstam, who had lied to him by denying that her husband had written "anything rash"[27] – but continued to befriend Pasternak.

Soon after Mandelstam's arrest, Bukharin was delegated to prepare the official report on poetry for the First Soviet Writers' Congress, in August 1934. He could not any longer risk mentioning Mandelstam in his speech to the congress, but did devote a large section of his speech to Pasternak, whom he described as "remote from current affairs ... a singer of the old intelligensia ... delicate and subtle ... a wounded and easily vulnerable soul. He is the embodiment of chaste but self-absorbed laboratory craftsmanship".[28] His speech was greeted with wild applause, though it greatly offended some of the listeners, such as the communist poet Semyon Kirsanov, who complained: "according to Bukharin, all the poets who have used their verses to participate in political life are out of date, but the others are not out of date, the so-called pure (and not so pure) lyric poets."[29]

When Bukharin was arrested two years later, Boris Pasternak displayed extraordinary courage by having a letter delivered to Bukharin's wife saying that he was convinced of his innocence.[30]

Increasing tensions with Stalin

Stalin's collectivization policy proved to be as disastrous as Bukharin predicted, but Stalin had by then achieved unchallenged authority in the party leadership. However, there were signs that moderates among Stalin's supporters sought to end official terror and bring a general change in policy, after mass collectivization was largely completed and the worst was over. Although Bukharin had not challenged Stalin since 1929, his former supporters, including Martemyan Ryutin, drafted and clandestinely circulated an anti-Stalin platform, which called Stalin the "evil genius of the Russian Revolution".

However,

Great Purge

In February 1936, shortly before the purge started in earnest, Bukharin was sent to Paris by Stalin to negotiate the purchase of the Marx and Engels archives, held by the

Bukharin, who had been forced to follow the Party line since 1929, confided to his old friends and former opponents his real view of Stalin and his policy. His conversations with

According to Nicolaevsky, Bukharin spoke of "the mass annihilation of completely defenseless men, with women and children" under forced collectivization and liquidation of kulaks as a class that dehumanized the Party members with "the profound psychological change in those communists who took part in the campaign. Instead of going mad, they accepted terror as a normal administrative method and regarded obedience to all orders from above as a supreme virtue. ... They are no longer human beings. They have truly become the cogs in a terrible machine."[34]

Yet to another Menshevik leader, Fyodor Dan, he confided that Stalin became "the man to whom the Party granted its confidence" and "is a sort of a symbol of the Party" even though he "is not a man, but a devil."[35] In Dan's account, Bukharin's acceptance of the Soviet Union's new direction was thus a result of his utter commitment to Party solidarity.

To his boyhood friend, Ilya Ehrenburg, he expressed the suspicion that the whole trip was a trap set up by Stalin. Indeed, his contacts with Mensheviks during this trip were to feature prominently in his trial.

Trial

Stalin was for a long time undecided on Bukharin and

Bukharin was tried in the

Even more than earlier Moscow show trials, Bukharin's trial horrified many previously sympathetic observers as they watched allegations become more absurd than ever and the purge expand to include almost every living Old Bolshevik leader except Stalin.[citation needed] For some prominent Communists such as Bertram Wolfe, Jay Lovestone, Arthur Koestler, and Heinrich Brandler, the Bukharin trial marked their final break with Communism and even turned the first three into passionate anti-Communists eventually.[37]

Bukharin wrote letters to Stalin while imprisoned, attempting without success to negotiate his innocence in the case of the alleged crimes, his eventual execution, and his hoped for release.

If I'm to receive the death sentence, then I implore you beforehand, I entreat you, by all that you hold dear, not to have me shot. Let me drink poison in my cell instead (let me have morphine so that I can fall asleep and never wake up). For me, this point is extremely important. I don't know what words I should summon up in order to entreat you to grant me this as an act of charity. After all, politically, it won't really matter, and, besides, no one will know a thing about it. But let me spend my last moments as I wish. Have pity on me![38]

In his letter of 10 December 1937, Bukharin suggests becoming Stalin's tool against Trotsky, but there's no evidence Stalin ever seriously considered Bukharin's offer.

If, contrary to expectation, my life is to be spared, I would like to request (though I would first have to discuss it with my wife) the following:

- ) that I be exiled to America for x number of years. My arguments are: I would myself wage a campaign [in favour] of the trials, I would wage a mortal war against Trotsky, I would win over large segments of the wavering intelligentsia, I would in effect become Anti-Trotsky and would carry out this mission in a big way and, indeed, with much zeal. You could send an expert security officer [chekist] with me and, as added insurance, you could detain my wife here for six months until I have proven that I am really punching Trotsky and Company in the nose, etc.

- ) But if there is the slightest doubt in your mind, then exile me to a camp in Pechora or Kolyma, even for 25 years. I could set up there the following: a university, a museum of local culture, technical stations and so on, institutes, a painting gallery, an ethnographic museum, a zoological and botanical museum, a camp newspaper and journal.[39]

While Anastas Mikoyan and Vyacheslav Molotov later claimed that Bukharin was never tortured and his letters from prison do not give the suggestion that he was tortured, it is also known that his interrogators were given the order: "beating permitted".[citation needed] Bukharin held out for three months, but threats to his young wife and infant son, combined with "methods of physical influence" wore him down.[40] But when he read his confession amended and corrected personally by Stalin, he withdrew his whole confession. The examination started all over again, with a double team of interrogators.[41][42]

Bukharin's confession and his motivation became subject of much debate among Western observers, inspiring Koestler's acclaimed novel Darkness at Noon and a philosophical essay by Maurice Merleau-Ponty in Humanism and Terror. His confessions were somewhat different from others in that while he pleaded guilty to the "sum total of crimes", he denied knowledge when it came to specific crimes. Some astute observers noted that he would allow only what was in the written confession and refuse to go any further.

There are several interpretations of Bukharin's motivations (besides being coerced) in the trial. Koestler and others viewed it as a true believer's last service to the Party (while preserving the little amount of personal honor left) whereas Bukharin biographer Stephen Cohen and Robert Tucker saw traces of

The result was a curious mix of fulsome confessions (of being a "degenerate fascist" working for the "restoration of capitalism") and subtle criticisms of the trial. After disproving several charges against him (one observer noted that he "proceeded to demolish or rather showed he could very easily demolish the whole case"[44]) and saying that "the confession of the accused is not essential. The confession of the accused is a medieval principle of jurisprudence" in a trial that was solely based on confessions, he finished his last plea with the words:

... the monstrousness of my crime is immeasurable especially in the new stage of struggle of the U.S.S.R. May this trial be the last severe lesson, and may the great might of the U.S.S.R. become clear to all.[45]

The state prosecutor, Andrey Vyshinsky, characterized Bukharin as an "accursed crossbreed of fox and pig" who supposedly committed a "whole nightmare of vile crimes".

While in prison, he wrote at least four book-length manuscripts including a lyrical autobiographical novel, How It All Began, a philosophical treatise, Philosophical Arabesques, a collection of poems, and Socialism and Its Culture – all of which were found in Stalin's archive and published in the 1990s.

Execution

Among other intercessors, the French author and

According to

Despite the promise to spare his family, Bukharin's wife, Anna Larina, was sent to a labor camp, but she survived to see her husband officially rehabilitated by the Soviet state under Mikhail Gorbachev in 1988.[49][50][51][52] Their son, Yuri Larin (born 1936), was sent to an orphanage in an attempt to keep him safe from the authorities, and also lived to see his rehabilitation.[53] His first wife, Nadezhda, died in a labor camp after being arrested in 1938. His second wife, Esfir' Gurvich, and their daughter Svetlana Gurvich-Bukharina (born 1924), were arrested in 1949, but survived past 1988, though they had lived in fear of the government their whole lives.[54]

Political stature and achievements

Bukharin was immensely popular within the party throughout the twenties and thirties, even after his fall from power. In his testament, Lenin portrayed him as the Golden Boy of the party,[55] writing:

Speaking of the young C.C. members, I wish to say a few words about Bukharin and Pyatakov. They are, in my opinion, the most outstanding figures (among the youngest ones), and the following must be borne in mind about them: Bukharin is not only a most valuable and major theorist of the Party; he is also rightly considered the favourite of the whole Party, but his theoretical views can be classified as fully Marxist only with great reserve, for there is something scholastic about him (he has never made a study of the dialectics, and, I think, never fully understood it) ... Both of these remarks, of course, are made only for the present, on the assumption that both these outstanding and devoted Party workers fail to find an occasion to enhance their knowledge and amend their one-sidedness.

Bukharin made several notable contributions to Marxist–Leninist thought, most notably The Economics of the Transition Period (1920) and his prison writings, Philosophical Arabesques,

His ideas, especially in economics and the question of market socialism, later became highly influential in the Chinese socialist market economy and Deng Xiaoping's economic reforms.[58][59]

British author Martin Amis argues that Bukharin was perhaps the only major Bolshevik to acknowledge "moral hesitation" by questioning, even in passing, the violence and sweeping reforms of the early Soviet Union. Amis writes that Bukharin said "during the Civil War he had seen 'things that I would not want even my enemies to see'."[60]

Works

Books and articles

- 1915: Toward a Theory of the Imperialist State

- 1917: Imperialism and World Economy

- 1917: The Russian Revolution and Its Significance

- 1918: Anarchy and Scientific Communism

- 1918: Programme of the World Revolution

- 1919: Economic Theory of the Leisure Class (written 1914)

- 1919: Church and School in the Soviet Republic

- 1919: The Red Army and the Counter Revolution

- 1919: Soviets or Parliament

- 1920: The ABC of Communism (with Evgenii Preobrazhensky)

- 1920: On Parliamentarism

- 1920: The Secret of the League (Part I)

- 1920: The Secret of the League (Part II)

- 1920: The Organisation of the Army and the Structure of Society

- 1920: Common Work for the Common Pot

- 1921: The Era of Great Works

- 1921: The New Economic Policy of Soviet Russia

- 1921: Historical Materialism: A System of Sociology

- 1922: Economic Organization in Soviet Russia

- 1923: A Great Marxian Party

- 1923: The Twelfth Congress of the Russian Communist Party

- 1924: Imperialism and the Accumulation of Capital

- 1924: The Theory of Permanent Revolution

- 1926: Building Up Socialism

- 1926: The Tasks of the Russian Communist Party

- 1927: The World Revolution and the U.S.S.R.

- 1928: New Forms of the World Crisis

- 1929: Notes of an Economist

- 1930: Finance Capital in Papal Robes. A Challenge!

- 1931: Theory and Practice from the Standpoint of Dialectical Materialism

- 1933: Marx's Teaching and Its Historical Importance

- 1934: Poetry, Poetics and the Problems of Poetry in the U.S.S.R.

- 1937–1938: How It All Began, a largely autobiographical novel, written in prison and first published in English in 1998.[61]

Cartoons

Bukharin was a cartoonist who left many cartoons of contemporary Soviet politicians. The renowned artist Konstantin Yuon once told him: "Forget about politics. There is no future in politics for you. Painting is your real calling."[62] His cartoons are sometimes used to illustrate the biographies of Soviet officials. Russian historian Yury Zhukov stated that Nikolai Bukharin's portraits of Joseph Stalin were the only ones drawn from the original, not from a photograph.[63]

References

- ^ a b Cohen 1980, p. 6.

- ISBN 978-1-4008-8817-7.

- ^ Lenin wrote a preface to Bukharin's book, Imperialism and the World Economy (Lenin Collected Works, Moscow, Volume 22, pages 103–107).

- ^ a b Cohen 1980, p. 44.

- ^ Isaac Deutscher, The Prophet Armed: Trotsky 1879–1921 (Vintage Books: New York, 1965) p. 246.

- ^ Cohen 1980, p. 46.

- ^ Cohen 1980, p. 49.

- ^ a b Cohen 1980, p. 50.

- ^ Leonard Shapiro, The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Vintage Books: New York, 1971) pp. 175 and 647.

- ^ Cohen 1980, p. 51.

- ^ Cohen 1980, p. 53.

- ^ Cohen 1980, pp. 43–44.

- ^ ISBN 0-674-07830-6. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- , etc.) (p. 178).

- ^ a b c Stephen F. Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography, 1888–1938 (1980)

- ^ RUSSIA: Humble Pie, Time, 25 October 1926.

- ^ Cohen 1980, p. 216.

- ^ a b Coehn, 1980.

- ^ Paul R. Gregory, Politics, Murder, and Love in Stalin's Kremlin: The Story of Nikolai Bukharin and Anna Larina (2010) ch 3–6.

- ^ Humbert-Droz, Jules (1971). De Lénine à Staline: Dix ans au service de l'Internationale communiste, 1921–1931.

- ^ Paul R. Gregory, Politics, Murder, and Love in Stalin's Kremlin: The Story of Nikolai Bukharin and Anna Larina (2010) ch 17.

- ^ Robert Service. Stalin: A Biography (2005) p 260.

- ^ Nicolaevsky, Boris. Power and the Soviet Elite. pp. 15–16.

- ^ Tokaev, Grigory. Comrade X. p. 43.

- ISBN 978-1-59558-056-6.

- ^ Mandelstam, Nadezhda (1971). Hope Against Hope, a Memoir, (translated by Max Hayward). London: Collins & Harvill. p. 113.

- ^ Mandelstam, Nadezhda. Hope Against Hope. p. 22.

- ^ Gorky, Maxim; Karl Radek; Nikolai Bukharin; et al. (1977). Soviet Writers' Congress 1934, the Debate on Socialist Realism and Modernism. London: Lawrence & Wishart. p. 233.

- ISBN 0-393-01357-X.

- ^ Medvedev, Roy. Nikolai Bukharin. p. 138.

- ^ Nikolaevsky, Boris, The Kirov Assassination, The New Leader, 23 August 1941.

- ISBN 0-19-505579-9.

- ^ A. Yakovlev, "O dekabr'skoi tragedii 1934", Pravda, 28 January 1991, p. 3, cited in J. Arch Getty, "The Politics of Repression Revisited", in ed., J. Arch Getty and Roberta T. Manning, Stalinist Terror: New Perspectives, New York, 1993, p. 46.

- ^ Nicolaevsky, Boris. Power and the Soviet Elite, New York, 1965, pp. 18–19.

- ISBN 0-385-47954-9. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-297-82108-3.

- ^ Bertram David Wolfe, "Breaking with Communism", p. 10; Arthur Koestler, Darkness at Noon, p. 258.

- ^ Bukharin's Letter to Stalin, 10 December 1937

- ^ J. Arch Getty and Oleg V. Naumov, The Road to Terror "Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932–1939"

- ^ Orlando Figes, Revolutionary Russia, 1891–1991, Pelican Books, 2014, p. 273.

- ^ Robert Conquest, The Great Terror: A Reassessment, pp. 364–65.

- ^ Helen Rappaport, Joseph Stalin: A Biographical Companion (1999) p 31.

- ^ Stephen J. Lee, Stalin and the Soviet Union (2005) p. 33.

- ^ Report by Viscount Chilston (British ambassador) to Viscount Halifax, No.141, Moscow, 21 March 1938.

- ^ Robert Tucker, Report of Court Proceedings in the Case of the Anti-Soviet "Block of Rights and Trotskyites", pp. 667–68.

- ^ Radzinsky, p. 384.

- ^ "Репрессии Членов Академии Наук".

- ISBN 1-85043-980-X, 9781850439806, chapter 14, p. 296.

- ^ Taubman, Philip (6 February 1988). "50 Years After His Execution, Soviet Panel Clears Bukharin". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Barringer, Felicity (8 February 1988). "Widow of Bukharin Fulfills Her Mission 50 Years Later". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Stanley, Alessandra (26 February 1996). "Anna Larina, 82, the Widow Of Bukharin, Dies in Moscow". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ Remnick, David (6 December 1988). "The Victory of Bukharin's Widow". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- JSTOR 40395110.

- ^ Cohen, Stephen F. (2013). The Victims Return: Survivors of the Gulag After Stalin. Bloomsbury.

- ^ Westley, Christopher (30 March 2011) A Bolshevik Love Story Archived 15 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Mises Institute.

- ISBN 978-1-58367-102-3,

- ^ Philip Arestis A Biographical Dictionary of Dissenting Economists, p. 88.

- ISBN 978-0-19-939203-2.

- JSTOR 152301.

- ^ Amis, Martin. Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million (Hyperion, 2001), p. 115.

- ^ Nikolai Bukharin, How It All Began. Translated by George Shriver, Columbia University Press]

- ^ "Russkiy Mir, "Love for a woman determines a lot in life" – Interview with Yuri Larin, 7 August 2008".[permanent dead link]

- ^ KP.RU // «Не надо вешать всех собак на Сталина» at www.kp.ru (Komsomolskaya Pravda)

Bibliography

- Bergmann, Theodor, and Moshe Lewin, eds. Bukharin in retrospect (Routledge, 2017).

- Biggart, John. "Bukharin and the origins of the 'proletarian culture' debate". Soviet Studies 39.2 (1987): 229–246.

- Biggart, John. "Bukharin's Theory of Cultural Revolution" in: Anthony Kemp-Welch (Ed.), The Ideas of Nikolai Bukharin. Oxford: Clarendon Press (1992), 131–158.

- Coates, Ken (2010). Who Was This Bukharin?. Nottingham: Spokesman. ISBN 978-0-85124-781-6.

- ISBN 0-19-502697-7.

- Gregory, Paul R. (2010). Politics, Murder, and Love in Stalin's Kremlin: The Story of Nikolai Bukharin and Anna Larina. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-1034-1.

- Kotkin, Stephen (2014). Stalin: Volume 1: The Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928.

- Littlejohn, Gary. "State, plan and market in the transition to socialism: the legacy of Bukharin". Economy and Society 8.2 (1979): 206–239.

- ISBN 0-330-41913-7.

- Smith, Keith. "Introduction to Bukharin: economic theory and the closure of the Soviet industrialisation debate". Economy and Society 8.4 (1979): 446–472.

- A. Andreev; D. Tsygankov, eds. (2010). Imperial Moscow University: 1755–1917: encyclopedic dictionary. Moscow: Russian political encyclopedia (ROSSPEN). pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-5-8243-1429-8.

Primary sources

- Bukharin, Nikolaĭ, and Evgeniĭ Alekseevich Preobrazhenskiĭ. ABC of Communism (Socialist Labour Press, 1921). online

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. "The ABC of Communism Revisited". Studies in East European Thought 70.2–3 (2018): 167–179.

- Bukharin, Nikolaĭ Ivanovich. Selected Writings on the State and the Transition to Socialism (M. E. Sharpe, 1982).

External links

- Nikolai Bukharin archive at marxists.org

- Bukharin's death-cell letter to Stalin

- How it all began, Bukharin's last letter to his wife

- A site dedicated to Bukharin

- A Bolshevik Love Story Archived 15 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Mises Institute

- February–March Plenum discussions transcript (in Russian) on which Bukharin was finally defeated, humiliated and expelled from Party

- Some of Bukharin's famous cartoons Archived 2 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Newspaper clippings about Nikolai Bukharin in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW