Norma (constellation)

| Constellation | |

| Visible at latitudes between +30° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of July. |

Norma is a small constellation in the

Four of Norma's brighter stars—Gamma, Delta, Epsilon and Eta—make up a square in the field of faint stars. Gamma2 Normae is the brightest star with an apparent magnitude of 4.0. Mu Normae is one of the most luminous stars known, with a luminosity between a quarter million and one million times that of the Sun. Four star systems are known to harbour planets. The Milky Way passes through Norma, and the constellation contains eight open clusters visible to observers with binoculars. The constellation also hosts Abell 3627, also called the Norma Cluster, one of the most massive galaxy clusters known.

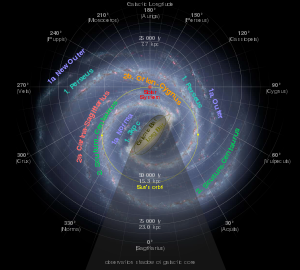

From the perspective of an observer on Earth, the Norma Arm of the Milky Way passes through the constellation Norma, and it's from the constellation that the arm's name is derived.

History

Norma was introduced in 1751–52 by

Characteristics

Norma is bordered by Scorpius to the north, Lupus to the northwest, Circinus to the west, Triangulum Australe to the south and Ara to the east. Covering 165.3 square degrees and 0.401% of the night sky, it ranks 74th of the 88 constellations in size.[7] The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is "Nor".[8] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of ten segments. In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 15h 12m 13.6119s and 16h 36m 08.3235s, while the declination coordinates are between −42.27° and −60.44°.[1] The whole constellation is visible to observers south of latitude 29°N.[b]

Features

Stars

Lacaille charted and designated ten stars with the Bayer designations Alpha through to Mu in 1756, however his Alpha Normae was transferred into Scorpius and left unnamed by Francis Baily, before being named N Scorpii by Benjamin Apthorp Gould, who felt its brightness warranted recognition. Though Beta Normae was depicted on his star chart, it was inadvertently left out of Lacaille's 1763 catalogue, was likewise transferred to Scorpio by Baily and named H Scorpii by Gould.[9] Norma's brightest star, Gamma2 Normae, is only of magnitude 4.0. Overall, there are 44 stars within the constellation's borders brighter than or equal to apparent magnitude 6.5.[c][7]

The four main stars—Gamma, Delta, Epsilon and Eta—make up a square in this region of faint stars.

Iota1 Normae is a multiple star system. The AB (mag 5.2 and 5.76) pair orbit each other with a period of 26.9 years; they are 2.77 and 2.71 times as massive as the Sun respectively.[17] The pair are 128 ± 6 light-years distant from Earth.[12] A third component is a yellow main sequence star of spectral type G8V with an apparent magnitude of 8.02.[17]

Exoplanets

Four star systems are known to harbour planets.

Deep-sky objects

Due to its location on the Milky Way, this constellation contains many

Located around 4900 light-years distant is Shapley 1 (or PK 329+02.1), a planetary nebula better known as the Fine-Ring Nebula. Appearing ring-shaped, it is thought that it actually is cylindrical and oriented directly at Earth. Around 8700 years old,[43] it lies about five degrees west-northwest of Gamma1 Normae. Its integrated magnitude is 13.6 and its mean surface brightness is 13.9. The central star is a white dwarf of magnitude 14.03. Mz 1 is a bipolar planetary nebula, thought to be an hourglass shape tilted at an angle to observers on Earth, some 3500 light-years distant.[44] Mz 3—known as the Ant Nebula as it resembles an ant—has a complex appearance, with at least four outflow jets and two large lobes visible.[45]

Approximately 200 million light-years from Earth with a redshift of 0.016 is Abell 3627; also called the Norma Cluster, it is one of the most massive galaxy clusters known to exist, at ten times the average cluster mass. Abell 3627 is thus theorized to be the Great Attractor, a massive object that is pulling the Local Group, the Virgo Supercluster, and the Hydra–Centaurus Supercluster towards its location at 600–1000 kilometres per second.[46]

Meteor shower

The relatively weak meteor shower Gamma Normids (GNO), which is typically active from March 7 to 23, peaking on March 15, has its radiant near Gamma2 Normae.[47]

Galactic Arm

The

Notes

- ^ The exception is Mensa, named for the Table Mountain.[4]

- ^ While parts of the constellation technically rise above the horizon to observers between 29°N and 48°N, stars within a few degrees of the horizon are to all intents and purposes unobservable.[7]

- ^ Objects of magnitude 6.5 are among the faintest visible to the unaided eye in suburban-rural transition night skies.[10]

References

- ^ a b c "Norma, Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ a b Ridpath, Ian. "Lacaille's Southern Planisphere of 1756". Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ Lacaille, Nicolas-Louis (1756). "Relation abrégée du Voyage fait par ordre du Roi au cap de Bonne-espérance". Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences (in French): 519– [589].

- ^ a b Wagman 2003, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Lacaille's Grouping of Norma, Circinus, and Triangulum Australe". Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ Wagman 2003, p. 215.

- ^ a b c Ridpath, Ian. "Constellations: Lacerta–Vulpecula". Star Tales. Self-published. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ^ Wagman 2003, pp. 215–16.

- ^ Bortle, John E. (February 2001). "The Bortle Dark-Sky Scale". Sky & Telescope. Sky Publishing Corporation. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Bibcode:2005MNSSA..64..107S.

- ^ S2CID 18759600.

- ^ Kaler, James B. "Gamma-2 Normae". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- S2CID 119387088.

- ^ "Eta Normae". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- S2CID 118665352.

- ^ . A69.

- S2CID 118847528. 10.

- ^ Kaler, James B. (30 July 2010). "Mu Normae". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Otero, Sebastian Alberto (24 May 2012). "QU Normae". The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-750-30654-6.

- ^ Otero, Sebastian Alberto (19 March 2011). "T Normae". The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (4 January 2010). "S Normae". The International Variable Star Index. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- S2CID 34133110.

- ^ Weule, Genelle (20 November 2018). "Spectacular cosmic pinwheel is a 'ticking bomb' set to blast gamma rays across the Milky Way". ABC News. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- S2CID 119294221.

- arXiv:1211.2475v2 [astro-ph.SR].

- S2CID 28693293.

- ^ S2CID 15659561.

- S2CID 13345357.

- S2CID 27097399.

- S2CID 53486907. 52.

- ^ "ESA News Release: Swift, Fermi probe fireworks from flaring gamma-ray star". Spaceflight Now. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- S2CID 53399981.

- S2CID 59157984.

- S2CID 118845989.

- S2CID 119224845.

- S2CID 5233877.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4419-0325-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4419-1777-5.

- .

- S2CID 119207107.

- S2CID 119164201.

- S2CID 119442827.

- S2CID 2203000.

- ISBN 978-1-55407-175-3.

- ^ Lunsford, Robert. "Meteor Activity Outlook for March 21-27, 2015". American Meteor Society. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

Sources

- Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, Virginia: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.