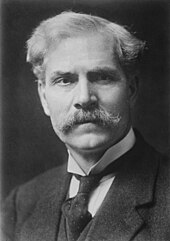

Norman Birkett, 1st Baron Birkett

Lord Justice of Appeal | |

|---|---|

| In office 30 September 1950 – 5 January 1957 | |

| Preceded by | Sir James Tucker |

| Succeeded by | Sir Frederic Sellers |

| Justice of the High Court | |

| In office 11 November 1941 – 30 September 1950 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Anthony Hawke |

| Succeeded by | Sir William McNair |

| Member of Parliament for Nottingham East | |

| In office 30 May 1929 – 27 October 1931 | |

| Preceded by | Edmund Brocklebank |

| Succeeded by | Louis Gluckstein |

| In office 6 December 1923 – 29 October 1924 | |

| Preceded by | John Houfton |

| Succeeded by | Edmund Brocklebank |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 September 1883 Ulverston, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 10 February 1962 (aged 78) London, England |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse | Ruth Nilsson |

| Children | 2, including Michael |

| Alma mater | Emmanuel College, Cambridge |

| Profession |

|

William Norman Birkett, 1st Baron Birkett,

Birkett received his education at

Declared medically unfit for military service during

Despite refusing appointment to the

Described as "one of the most prominent Liberal barristers in the first half of the 20th century" and "the Lord Chancellor that never was",[1] Birkett was noted for his skill as a speaker, which helped him defend clients with almost watertight cases against them. As an alternate judge, Birkett was not allowed a vote at the Nuremberg Trials, but his opinion helped shape the final judgment. During his tenure in the Court of Appeal he oversaw some of the most significant cases of the era, particularly in contract law, despite his avowed dislike of judicial work.

Early life and education

Norman was born in

At Cambridge, Birkett preached on the local Methodist circuit and at

He gained a Second Class in the Part I History

While working for Cadbury, Birkett befriended Ruth "Billy" Nilsson, and after he had proposed to her several times, she agreed to marry him. Nilsson gave up her position at Bourneville to move to London and they were married on 25 August 1920.

Practice at the Bar and time as a member of parliament

After qualifying as a barrister, he moved to Birmingham in 1914, choosing the city because he had some connections there thanks to his association with Cadbury,[20] and began work at the chambers of John Hurst.[1] His career was aided by the outbreak of World War I; many of the younger and fitter barristers were called up for war service, whilst Birkett himself, who was thirty when he joined the bar, avoided conscription as he was declared medically unfit. He was suffering from tuberculosis, and he returned to Ulverston for six months to recover.[1] During his time in Birmingham, he continued his work as a minister, regularly preaching at the Baptist People's Chapel.[21]

Birkett became a popular defence counsel, something that on occasion caused him trouble; he was once forced to refuse a defendant's request to act as his representative because Birkett was expected in a different court.[22] He impressed the Bench in Birmingham so much that, in 1919, he was advised by a local Circuit Judge to move to London to advance his career.[23] Although he was initially hesitant, saying that "competition in London is on quite a different scale, and if I failed there, I would have lost everything I have built up here", a case he took in 1920 changed the situation. He acted as a junior for the prosecution in the so-called Green Bicycle Case against Edward Marshall Hall. Although he lost, he sufficiently impressed Marshall Hall for the latter to offer him a place in his chambers in London.[17] He had no connections with the solicitors in London, and the clerk at his new chambers got around this lack of contacts by using him as counsel in cases involving Marshall Hall, who as a King's Counsel could appear in court only when accompanied by a junior barrister such as Birkett.[24]

Member of Parliament

His father had been a supporter of the Liberal Party, and Birkett had helped campaign for them during the 1906 general election.[1] He had been invited to become the Liberal candidate for Cambridge in 1911, but he refused because he had no income; he did, however, help his employer George Cadbury, Jr. get elected as a Liberal Councillor in Birmingham and helped start a branch of the National League of Young Liberals in the city.[1] Birkett was the Liberal candidate for

Birkett's maiden speech in Parliament responded to a proposal by

He applied to become a

In 1924, the Campbell Case brought down the Labour minority government and forced a general election.[33] Birkett returned to Nottingham East to campaign for his re-election, though he faced a much more difficult job than he had in 1923. The Conservative candidate, Edmund Brocklebank, was much stronger than in the previous election, and the left-wing vote was split because he was also campaigning against Tom Mann, a noted Communist.[34] A few days before the election, the Zinoviev letter, allegedly addressed to the Communist Party, was published that mentioned organising uprisings in British colonies; fear of the "socialist menace" drove many voters to the right, and in the election on 29 October 1924, many Liberal members of parliament, including Birkett, lost their seats to Conservatives.[34]

Practice at the Bar in London

While working with Marshall Hall, Birkett was involved in several notable criminal cases that helped cement his reputation as an outstanding speaker at the Bar.[35]

In 1925, a case known as the "Bachelor's Case" came up at the High Court of Justice between Lieutenant-Colonel Ian Dennistoun and his ex-wife Dorothy Dennistoun.[35] When the Dennistouns divorced, Mr. Dennistoun could not pay ancillary relief. He instead promised that he would provide for his ex-wife in the future when he had the money.[35] Some time after the divorce, Mr. Dennistoun married Almina Herbert, Countess of Carnarvon, the widow of Lord Carnarvon, a rich woman thanks to the terms of her husband's will, who provided for her new husband. After hearing about this, Dorothy Dennistoun demanded the alimony money she had been promised. Lady Carnarvon saw this as blackmail and persuaded her new husband to take his wife to court for what Sir Henry McCardie, who tried the case, called "the most bitterly conducted litigation I have ever known".[35] Marshall Hall and Birkett both worked on the case representing Lady Carnarvon and Mr. Dennistoun, while Ellis Hume-Williams, one of the most respected divorce barristers of the day, represented Mrs. Dennistoun.[35]

The case initially appeared to be going badly for Marshall Hall. An inept cross-examination on his part weakened his argument,

Return to politics

Birkett was returned as MP for Nottingham East at the general election on 31 May 1929 in which he won 14,049 votes, taking the seat with a majority of 2,939.[44]

As the largest single party, the Labour Party formed a

Despite having to juggle his career at the Bar and as a member of parliament, Birkett kept up a good attendance in the House of Commons, and along with

After an economic crisis in 1931, the King dissolved parliament and Birkett returned to Nottingham East to defend his seat; his main opponent was the Conservative, Louis Gluckstein, who had challenged him in the 1929 election.[51] The Conservative Party's support of protectionism met with approval from the electorate, as most were employed in industries which had suffered after the institution of free trade. Gluckstein won the general election on 27 October 1931 with a majority of 5,583 votes.

On 3 November, Birkett was informed that if he had been returned, the Prime Minister intended to make him Solicitor-General.[51] Disillusioned with the circumstances of the election, Birkett "[bade] farewell to East Nottingham" and retired from politics.[52] He was invited to become a Liberal candidate two more times; once in 1931 for Torquay and once in 1932 for North Cornwall.[52] The second was a tempting offer; the seat had become vacant on the death of its previous holder, a National Liberal with a comfortable majority, and it was felt that Birkett was almost certain to be returned to Parliament.[52] Despite this, he refused, disliking the National Liberal policies and the extent to which they had aligned themselves with the Conservative Party.[53]

Return to the Bar

In 1930, Birkett was involved in the so-called

The cross-examination of him and other witnesses by Birkett swayed the jury, and they took only fifteen minutes to find Rouse guilty of murder.[58] After his appeal had been rejected by both the Court of Appeal and the Home Secretary, Rouse admitted that he had in fact committed the murder – although he never gave a reason – it was theorised that he had done so in an attempt to fake his own death.[59] Despite his admission of guilt the identity of the victim has never been discovered.[57]

In 1934, Birkett acted as counsel for the second of the two Brighton trunk murders, a case which was described as "his greatest triumph in a capital case".[60] In June 1934, a woman's torso was found in a suitcase in Brighton railway station. The legs were discovered at King's Cross station the next day, but her head and arms were never found, and the case is still unsolved.[61] A woman by the name of Violette Kaye had disappeared, and the appearance of the first woman's body prompted greater scrutiny on Kaye's case.[61] On 14 July, they interviewed Toni Mancini, Kaye's boyfriend, who convinced them that the dead woman could not possibly be Kaye; the dead woman had been identified as around thirty five years old and five months pregnant, while Kaye was ten years older.[61] Kaye was last seen alive on 10 May looking distressed in the doorway to her house and had been scheduled to visit her sister in London who received a telegram on 11 May reading "Going abroad. Good job. Sail Sunday. Will write. Vi." in block capitals.[61] The post office clerks could not remember who sent it, but experts testified that the handwriting on the telegram had similarities to that on a menu written by Mancini.[61] On 14 May, with the help of another man, Mancini moved his belongings from the house he shared with Kaye, which included a large trunk which was too heavy to move by hand.[61] Mancini had told people that he had broken up with Kaye and she had moved to Paris, and that before she left he had beaten her.[61] He later said to a friend, "What is the good of knocking a woman about with your fists? You only hurt yourself. You should hit her with a hammer same as I did and [chop] her up."[61] A hammerhead was later found in the rubbish at his old house.[61]

After the police had left on 14 July, Mancini got on a train to London. When the police arrived the next morning, they were unable to find Mancini but found Kaye's body decomposing in the trunk in his new home.[62] They immediately sent out a country-wide call for Mancini to be arrested, and he was picked up near London.[62] He claimed he was not guilty, and stated during interviews with police that he had returned home to find Kaye dead. Fearing that with his criminal record, the police would not believe him, he had hidden the body in a trunk.[62] While Mancini was in prison, his solicitor phoned Birkett and asked him to work as counsel for the defence, which Birkett agreed to do.[62] In his defence, Birkett highlighted flaws in the prosecution's case to introduce an element of doubt in the minds of the jury. His cross-examination of Sir Bernard Spilsbury, famous Home Office pathologist and potentially the most dangerous witness for the Crown, was seen as "masterly".[63] Birkett also emphasised the affectionate nature of the relationship between Kaye and Mancini before Kaye's death.[64] Despite strong evidence that he had committed the crime, including marks on the victim's skull believed to be from a hammer and marks of blood on Mancini's clothing, the jury found Mancini not guilty after two and a half hours of deliberations.[65] Mancini confessed to the murder before dying.

In May 1937 Birkett was appointed Chairman of the Inter-Departmental Committee for Abortion set up by the

Judicial work

Birkett had been offered appointment to the

Nuremberg trials

On 30 August 1945, Birkett received a letter from the

The trial lasted from 18 October 1945 to 30 September 1946, and although Birkett did not have a vote in the proceedings as an alternate judge, his opinion was given weight, and it helped sway the decisions made by the main judges.[83] After returning home from the trials, he received praise from both the Lord Chancellor, who said that "The country owes much to him for vindicating our conceptions of an impartial trial under the rule of law",[82] and from John Parker, the American alternate judge, who wrote that:

Although only an alternate member of the tribunal without a vote, his voice was heard in all of its deliberations, his hand drafted a large and most important part of its judgment, and no one connected with the tribunal, member or otherwise, had a greater part than he in shaping the final result. If, as I confidently believe, the work of the tribunal will constitute a landmark in the development of world order based on law, to Norman Birkett must go a large share of the credit for the success of the undertaking. To few men does the opportunity come to labour so mightily for the welfare of their kind.[84]

After the judges returned home, Lawrence was made a Baron for his work at Nuremberg, but Birkett received nothing.

Further judicial work

The rest of his time in the High Court passed uneventfully,[85] but he continued to be unhappy with his work as a judge, noting that "I am nervous of myself, without much confidence in my judgment and hesitant about my sentences and damages and things of that kind. I have felt no glow of achievement in any summing up, though none of them have been bad."[87]

He was again struck by depression in 1948 when

He found the work in the Court of Appeal dull, and his disappointment increased the longer he worked.

Retirement

On 13 June 1957 he became chairman of a committee of

Birkett tried to sit as regularly in the House of Lords as possible, and made his maiden speech on 8 April 1959 on the subject of crime in the United Kingdom.[103] In May, he moved the first reading of the Obscene Publications Bill, which passed with support from both sides of the house. Privately, Birkett believed that "there will never be a satisfactory law in England about obscenity. Our 1959 Act is the best we have yet done."[104] In 1961, he was again invited by the BBC to give a series of talks on the BBC Home Service, this time titled "Six Great Advocates".[105] He picked Edward Marshall Hall, Patrick Hastings, Edward Clarke, Rufus Isaacs, Charles Russell and Thomas Erskine.[106] He sat for the last time in the House of Lords on 8 February 1962, where he made a speech criticising an element of the Manchester Corporation Bill which would have water drained from Ullswater to meet the needs of the growing population in Manchester.[107] His speech was "deeply felt and eloquent", and when the votes were announced, Birkett and his supporters had won by 70 votes to 36.[108] The Ullswater Yacht Club now holds an annual Lord Birkett Memorial Trophy Race on the lake.[109]

The next morning he complained of heart trouble, collapsed shortly after lunch and was taken to the hospital.[110] The doctors discovered that he had ruptured an important blood vessel and immediate surgery was needed to fix it.[111] The operation failed to fix the problem, and he died early in the morning on 10 February 1962.[112][113] His son, Michael, succeeded him as Baron Birkett.

Arms

|

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g Dale, Tom; Robert Ingham (Autumn 2002). "The Lord Chancellor Who Never Was". Journal of Liberal Democrat History.

- ^ Chandos (1963) p. 15.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 24.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 30.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 36.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 35.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 39.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 46.

- ^ Chandos (1963) p. 25.

- ^ a b c Chandos (1963) p. 26.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 42.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 48.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 49.

- ^ an undergraduate at Cambridge normally needs to pass a Part I and a Part 2, not necessarily in the same subject, to obtain a BA

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 57.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 63.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 91.

- ^ doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31899. Retrieved 24 January 2009. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ "The Course". Harewood Downs Golf Club. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ Chandos (1963) p. 31.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 74.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 77.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 85.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 93.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 116.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 118.

- ^ Hansard 1803–2005: House of Commons sitting of 20 February 1924, Mothers' Pensions

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 119.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 120.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 121.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 122.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 123.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 125.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e Hyde (1965) p. 135.

- ^ Chandos (1963) p. 48.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 139.

- ^ Chandos (1963) p. 49.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 154.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 158.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 162.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 266.

- ^ Chandos (1963) p. 65.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 269.

- ^ a b c d Hyde (1965) p. 270.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 322.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 324.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 325.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 326.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 327.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 330.

- ^ a b c Hyde (1965) p. 332.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 333.

- ^ a b c Hyde (1965) p. 298.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 299.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 300.

- ^ a b c Hyde (1965) p. 301.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 309.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 310.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 394.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hyde (1965) p. 395.

- ^ a b c d Hyde (1965) p. 396.

- ^ Andrew Rose, 'Lethal Witness' Sutton Publishing 2007, Kent State University Press 2009; pp 233-240, Chapter Twenty 'Tony Mancini: The Brighton Trunk Murders'.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 401.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 418.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 462.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 463.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 469.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 464.

- ^ Chandos (1963) p. 182.

- ^ "No. 37977". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 June 1941. pp. 2571–2572.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 471.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 474.

- ^ "No. 35346". The London Gazette (Supplement). 14 November 1941. pp. 6574–6575.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 476.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 483.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 484.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 486.

- ^ [1944] KB 693; Hyde (1965) p. 489.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 494.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 495.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 496.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 524.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 527.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 530.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 531.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 532.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 541.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 543.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 542.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 544.

- ^ a b c d Hyde (1965) p. 546.

- ^ Chandos (1963) p. 184.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 549.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 555.

- ^ "Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists (Southern) Ltd". BAILII. 5 February 1953. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 556.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 565.

- ^ a b Hyde (1965) p. 567.

- ^ "No. 41299". The London Gazette. 31 January 1958. pp. 690–691.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 568; the original speech was in Latin.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 570.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 580.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 587.

- ^ "Reviews and Notices". Law Quarterly Review. 78: 303. April 1962.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 606.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 610.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 618.

- ^ "Historic 'Steamer' Joins Lord Birkett Celebrations". Ullswater Steamers. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 619.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 620.

- ^ Hyde (1965) p. 621.

- ^ Chandos (1963) p. 200.

References

- Chandos, John (1963). Norman Birkett: Uncommon Advocate. Mayflower Publishing. OCLC 11641755.

- Hyde, H. Montgomery (1965). Norman Birkett: The Life of Lord Birkett of Ulverston. OCLC 255057963.