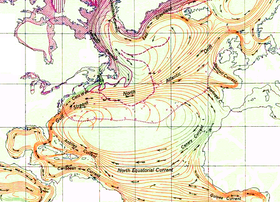

North Atlantic Gyre

The North Atlantic Gyre of the

In turn it is chiefly subdivided into the Gulf Stream flowing northward along the west; its often conflated continuation, the North Atlantic Current across the north; the Canary Current flowing southward along the east; and the Atlantic's North Equatorial Current in the south. The gyre has a pronounced thermohaline circulation, bringing salty water west from the Mediterranean Sea and then north to form the North Atlantic Deep Water.

The gyre traps anthropogenic (human-made) marine debris in its natural garbage or flotsam patch, in the same way the North Pacific Gyre has the Great Pacific garbage patch.[1]

At the heart of the gyre is the Sargasso Sea, noted for its still waters and quite dense seaweed accumulations.

Structure

Low air temperatures at high latitudes cause substantial sea-air heat flux, driving a density increase and convection in the water column. Open ocean convection occurs in deep plumes and is particularly strong in winter when the sea-air temperature difference is largest.[2] Of the 6 sverdrup (Sv) of dense water that flows southward over the GSR (Greenland-Scotland Ridge), 3 Sv does so via the Denmark Strait forming Denmark Strait Overflow Water (DSOW). 0.5-1 Sv flows over the Iceland-Faroe ridge and the remaining 2–2.5 Sv returns through the Faroe-Shetland Channel; these two flows form Iceland Scotland Overflow Water (ISOW). The majority of flow over the Faroe-Shetland ridge flows through the Faroe-Bank Channel and soon joins that which flowed over the Iceland-Faroe ridge, to flow southward at depth along the Eastern flank of the Reykjanes Ridge.

As ISOW overflows the GSR (Greenland-Scotland Ridge), it turbulently entrains intermediate density waters such as Sub-Polar Mode water and Labrador Sea Water. This grouping of water-masses then moves geostrophically southward along the East flank of Reykjanes Ridge, through the Charlie Gibbs Fracture Zone and then northward to join DSOW. These waters are sometimes referred to as Nordic Seas Overflow Water (NSOW). NSOW flows cyclonically following the surface route of the SPG (sub-polar gyre) around the Labrador Sea and further entrains Labrador Sea Water (LSW).[3]

Characteristically fresh Labrador Sea Water (LSW) is formed at intermediate depths by deep convection in the central Labrador Sea, particularly during winter storms.[2] This convection is not deep enough to penetrate into the NSOW layer which forms the deep waters of the Labrador Sea. LSW joins NSOW to move southward out of the Labrador Sea: while NSOW easily passes under the NAC at the North-West Corner, some LSW is retained. This diversion and retention by the SPG explains its presence and entrainment near the GSR (Greenland-Scotland Ridge) overflows. Most of the diverted LSW however splits off before the CGFZ (Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone) and remains in the western SPG. LSW production is highly dependent on sea-air heat flux and yearly production typically ranges from 3–9 Sv.[4][5] ISOW is produced in proportion to the density gradient across the Iceland-Scotland Ridge and as such is sensitive to LSW production which affects the downstream density[6][7] More indirectly, increased LSW production is associated with a strengthened SPG and hypothesized to be anti-correlated with ISOW[8][9][10] This interplay confounds any simple extension of a reduction in individual overflow waters to a reduction in AMOC. LSW production is understood to have been minimal prior to the 8.2 ka event,[11] with the SPG thought to have existed before in a weakened, non-convective state.[12]

There is a debate about the extent to which convection in the Labrador Sea plays a role in AMOC circulation, particularly in the connection between Labrador sea variability and AMOC variability.[13] Observational studies have been inconclusive about whether this connection exists.[14] New observations with the OSNAP array show little contribution from the Labrador Sea to overturning, and hydrographic observations from ships dating back to 1990 show similar results.[15] [16] Nevertheless, older estimates of LSW formation using different techniques suggest larger overturning.[17]

Seasonal variability

As with many oceanographic patterns, the North Atlantic Gyre experiences seasonal changes.

Data collected in the

The changes in oceanic

Lead contamination

Measured samples of

Garbage patch

See also

- Ocean current

- Oceanic gyre

- Volta do mar

References

- S2CID 13552090.

- ^ a b Marshall, John, and Friedrich Schott. "Open-ocean convection: Observations, theory, and models." Reviews of Geophysics 37.1 (1999): 1–64.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-6773-0.

- S2CID 56353963.

- S2CID 56353963.

- S2CID 129629709.

- S2CID 4419549. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- hdl:2060/20070032937.

- S2CID 13857911.

- PMID 29167464.

- S2CID 205016579.

- S2CID 16132704. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- S2CID 54013534.

- S2CID 59567598.

- ISSN 0022-3670.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-6774-7, retrieved 2022-05-23

- ^ Ninnemann, Ulysses S.; Thornalley, David J. R. (2016). "Recent natural variability of the Iceland Scotland Overflows on decadal to millennial timescales: Clues from the ooze". US CLIVAR Variations. 14 (3): 1–8. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- .

- .

- .

- S2CID 20038716.

- ^ "Mānoa: UH Mānoa scientist predicts plastic garbage patch in Atlantic Ocean | University of Hawaii News". manoa.hawaii.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- ^ Gorman, Steve (4 August 2009). "Scientists study huge ocean garbage patch". Perthnow.com.au. Archived from the original on 29 January 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ "Scientists find giant plastic rubbish dump floating in the Atlantic". Perthnow.com.au. 26 February 2010. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ Gill, Victoria (24 February 2010). "Plastic rubbish blights Atlantic Ocean". BBC News. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ Orcutt, Mike (2010-08-19). "How Bad Is the Plastic Pollution in the Atlantic?". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- S2CID 51944658.

- ^ "The garbage patch territory turns into a new state - United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". unesco.org. 22 May 2019.

- ^ "About". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 2019-11-08.

External links

- Ocean currents Archived 2022-01-20 at the Wayback Machine