Langues d'oïl

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

| Oïl | |

|---|---|

| Langues d'oïl, French | |

| Geographic distribution | Northern and central France, southern Belgium, Switzerland |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European |

Early forms | |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | oila1234 cent2283 (Central Oil) |

| |

The langues d'oïl (

Linguists divide the Romance languages of France, and especially of Medieval France, into two main geographical subgroups: the langues d'oïl to the North, and the langues d'oc in the Southern half of France. Both groups are named after the word for "yes" in them or their recent ancestral languages. The most common modern langue d'oïl is standard French, in which the ancestral "oïl" has become "oui".

Terminology

Langue d'oïl (in the singular), Oïl dialects and Oïl languages (in the plural) designate the ancient northern Gallo-Romance languages as well as their modern-day descendants. They share many linguistic features, a prominent one being the word oïl for yes. (Oc was and still is the southern word for yes, hence the langue d'oc or Occitan languages). The most widely spoken modern Oïl language is French (oïl was pronounced [o.il] or [o.i], which has become [wi], in modern French oui).[7]

There are three uses of the term oïl:

- Langue d'oïl

- Oïl dialects

- Oïl languages

Langue d'oïl

In the singular, langue d'oïl refers to the mutually intelligible linguistic variants of lingua romana spoken since the 9th century in northern France and southern Belgium (Wallonia), since the 10th century in the Channel Islands, and between the 11th and 14th centuries in England (the Anglo-Norman language). Langue d'oïl, the term itself, has been used in the singular since the 12th century to denote this ancient linguistic grouping as a whole. With these qualifiers, langue d'oïl sometimes is used to mean the same as Old French (see History below).[8]

Oïl dialects

In the plural, Oïl dialects refer to the varieties of the ancient langue d'oïl.[citation needed]

Oïl languages

Oïl languages are those modern-day descendants that evolved separately from the varieties of the ancient langue d'oïl. Consequently, langues d'oïl today may apply either: to all the modern-day languages of this family except the French language; or to this family including French. "Oïl dialects" or "French dialects" are also used to refer to the Oïl languages except French—as some extant Oïl languages are very close to modern French. Because the term dialect is sometimes considered pejorative, the trend today among French linguists is to refer to these languages as langues d'oïl rather than dialects.[citation needed]

Varieties

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (September 2022) |

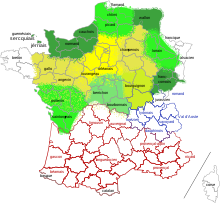

Five zones of partially

Frankish zone (zone francique)

- Picard

- Walloon

- Lorrain

- Northern Dgèrnésiais (spoken in Guernsey), Jèrriais (spoken in Jersey), Auregnais (spoken in Alderney), Sercquiais(spoken in Sark)

- Eastern Champenois

Francien zone (zone francienne)

Non-standard varieties:

- Orléanais

- Tourangeau, not to be confused with the French language in Touraine]

- Berrichon

- Bourbonnais

- Western Champenois (or Eastern Francien)

Burgundian zone (zone burgonde)

- Bourguignon

- Franc-Comtois

Armorican zone (zone armoricaine)

- Eastern Armorican: )

- Western Armorican: Gallo

Gallo has a stronger Celtic substrate from Breton. Gallo originated from the oïl speech of people from eastern and northern regions: Anjou; Maine (Mayenne and Sarthe); and Normandy; who were in contact with Breton speakers in Upper Brittany. See Marches of Neustria

Poitevin-Saintongeais zone (zone poitevine and zone saintongeaise)

Named after the former provinces of Poitou and Saintonge

- Poitevin

- Saintongeais

Development

For the history of phonology, orthography, syntax and morphology, see

Each of the Oïl languages has developed in its own way from the common ancestor, and division of the development into periods varies according to the individual histories. Modern linguistics uses the following terms:

- 9th–13th centuries

- Old French

- Old Norman

- etc.

- French

- Middle French for the period 14th–15th centuries

- 16th century: français renaissance (Renaissance French)

- 17th to 18th century: français classique (Classical French)

History

Romana lingua

In the 9th century, romana lingua (the term used in the

Many of the developments that are now considered typical of Walloon appeared between the 8th and 12th centuries. Walloon "had a clearly defined identity from the beginning of the thirteenth century". In any case, linguistic texts from the time do not mention the language, even though they mention others in the Oïl family, such as Picard and Lorrain. During the 15th century, scribes in the region called the language "Roman" when they needed to distinguish it. It is not until the beginning of the 16th century that we find the first occurrence of the word "Walloon" in the same linguistic sense that we use it today.

Langue d'oïl

By late- or post-Roman times Vulgar Latin within France had developed two distinctive terms for signifying assent (yes): hoc ille ("this (is) it") and hoc ("this"), which became oïl and oc, respectively. Subsequent development changed "oïl" into "oui", as in modern French. The term langue d'oïl itself was first used in the 12th century, referring to the Old French linguistic grouping noted above. In the 14th century, the Italian poet Dante mentioned the yes distinctions in his De vulgari eloquentia. He wrote in Medieval Latin: "nam alii oc, alii si, alii vero dicunt oil" ("some say 'oc', others say 'sì', others say 'oïl'")—thereby distinguishing at least three classes of Romance languages: oc languages (in southern France); si languages (in Italy and Iberia) and oïl languages (in northern France).[citation needed]

Other Romance languages derive their word for "yes" from the classical Latin sic, "thus", such as the Italian sì, Spanish and Catalan sí, Portuguese sim, and even French si (used when contradicting another's negative assertion). Sardinian is an exception in that its word for "yes", eja, is from neither origin.[10] Similarly Romanian uses da for "yes", which is of Slavic origin.[11]

However, neither lingua romana nor langue d'oïl referred, at their respective time, to a single homogeneous language but to

French (Old French/Standardized Oïl) or lingua Gallicana

In the 13th century these varieties were recognized and referred to as dialects ("idioms") of a single language, the langue d'oïl. However, since the previous centuries a common literary and juridical "interdialectary" langue d'oïl had emerged, a kind of koiné. In the late 13th century this common langue d'oïl was named French (françois in French, lingua gallica or gallicana in Medieval Latin). Both aspects of "dialects of a same language" and "French as the common langue d'oïl" appear in a text of Roger Bacon, Opus maius, who wrote in Medieval Latin but translated thus: "Indeed, idioms of a same language vary amongst people, as it occurs in the French language which varies in an idiomatic manner amongst the French, Picards, Normans and Burgundians. And terms right to the Picards horrify the Burgundians as much as their closer neighbours the French".[citation needed]

It is from this period though that definitions of individual Oïl languages are first found. The Picard language is first referred to by name as "langage pikart" in 1283 in the Livre Roisin. The author of the Vie du bienheureux Thomas Hélye de Biville refers to the Norman character of his writing. The Sermons poitevins of around 1250 show the Poitevin language developing as it straddled the line between oïl and oc.

As a result, in modern times the term langue d'oïl also refers to that Old French which was not as yet named French but was already—before the late 13th century—used as a literary and juridical interdialectary language.

The term

Rise of French (Standardized Oïl) versus other Oïl languages

For political reasons it was in Paris and Île-de-France that this koiné developed from a written language into a spoken language. Already in the 12th century Conon de Béthune reported about the French court who blamed him for using words of Artois.

By the late 13th century the written koiné had begun to turn into a spoken and written standard language, and was named French. Since then French started to be imposed on the other Oïl dialects as well as on the territories of langue d'oc.

However, the Oïl dialects and langue d'oc continued contributing to the lexis of French.

In 1539 the French language was imposed by the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts. It required Latin be replaced in judgements and official acts and deeds. The local Oïl languages had always been the language spoken in justice courts. The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts was not intended to make French a national language, merely a chancery language for law and administration. Although there were competing literary standards among the Oïl languages in the mediæval period, the centralisation of the French kingdom and its influence even outside its formal borders sent most of the Oïl languages into comparative obscurity for several centuries. The development of literature in this new language encouraged writers to use French rather than their own regional languages. This led to the decline of vernacular literature.

It was the French Revolution which imposed French on the people as the official language in all the territory. As the influence of French (and in the Channel Islands, English) spread among sectors of provincial populations, cultural movements arose to study and standardise the vernacular languages. From the 18th century and into the 20th century, societies were founded (such as the "Société liégoise de Littérature wallonne" in 1856), dictionaries (such as George Métivier's Dictionnaire franco-normand of 1870) were published, groups were formed and literary movements developed to support and promote the Oïl languages faced with competition. The Third Republic sought to modernise France and established primary education where the only language recognised was French. Regional languages were discouraged, and the use of French was seen as aspirational, accelerating their decline.[12] This was also generally the case in areas where Oïl languages were spoken. French is now the best-known of the Oïl languages.

Literature

Besides the influence of

As the vernacular Oïl languages were displaced from towns, they have generally survived to a greater extent in rural areas - hence a preponderance of literature relating to rural and peasant themes. The particular circumstances of the self-governing Channel Islands developed a lively strain of political comment, and the early industrialisation in Picardy led to survival of Picard in the mines and workshops of the regions. The mining poets of Picardy may be compared with the tradition of rhyming

There are some regional magazines, such as Ch'lanchron (Picard), Le Viquet (Norman), Les Nouvelles Chroniques du Don Balleine [1] (Jèrriais), and El Bourdon (Walloon), which are published either wholly in the respective Oïl language or bilingually with French. These provide a platform for literary writing.

Status

Apart from French, an official language in many countries (see

Currently Walloon,

The Norman languages of the Channel Islands enjoy a certain status under the governments of their

The French government recognises the Oïl languages as