Obsidian

| Obsidian | |

|---|---|

Translucent | |

| Other characteristics | Texture: Smooth; glassy |

| References | [4] |

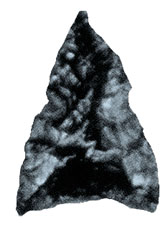

Obsidian (/əbˈsɪdi.ən, ɒb-/ əb-SID-ee-ən ob-)[5] is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock.[6]

Obsidian is produced from

Obsidian is hard,

Origin and properties

The Natural History by the Roman writer Pliny the Elder includes a few sentences about a volcanic glass called obsidian (lapis obsidianus), discovered in Ethiopia by Obsidius, a Roman explorer.[9][10][11][12]

Obsidian is formed from quickly cooled lava, which is the parent material.[13][14][15] Extrusive formation of obsidian may occur when felsic lava cools rapidly at the edges of a felsic lava flow or volcanic dome, or when lava cools during sudden contact with water or air. Intrusive formation of obsidian may occur when felsic lava cools along the edges of a dike.[16][17]

Tektites were once thought by many to be obsidian produced by lunar volcanic eruptions,[18] though few scientists now adhere to this hypothesis.[19]

Obsidian is mineral-like, but not a true mineral because, as a glass, it is not crystalline; in addition, its composition is too variable to be classified as a mineral. It is sometimes classified as a mineraloid.[20] Though obsidian is usually dark in color, similar to mafic rocks such as basalt, the composition of obsidian is extremely felsic. Obsidian consists mainly of SiO2 (silicon dioxide), usually 70% by weight or more. Crystalline rocks with a similar composition include granite and rhyolite. Because obsidian is metastable at the Earth's surface (over time the glass devitrifies, becoming fine-grained mineral crystals), obsidian older than Miocene in age is rare. Exceptionally old obsidians include a Cretaceous welded tuff and a partially devitrified Ordovician perlite.[21] This transformation of obsidian is accelerated by the presence of water. Although newly formed obsidian has a low water content, typically less than 1% water by weight,[22] it becomes progressively hydrated when exposed to groundwater, forming perlite.

Pure obsidian is usually dark in appearance, though the color varies depending on the impurities present. Iron and other

Occurrence

Obsidian is found near volcanoes in locations which have undergone rhyolitic eruptions. It can be found in Argentina,

There are only four major deposit areas in the central Mediterranean: Lipari, Pantelleria, Palmarola and Monte Arci (Sardinia).[28]

Ancient sources in the Aegean were Milos and Gyali.[29]

Acıgöl town and the Göllü Dağ volcano were the most important sources in central Anatolia, one of the more important source areas in the prehistoric Near East.[30][31][32]

Prehistoric and historical use

The first known archaeological evidence of usage was in

Europe

Obsidian artifacts first appeared in the European continent in Central Europe in the

Middle East and Asia

In the Ubaid in the 5th millennium BC, blades were manufactured from obsidian extracted from outcrops located in modern-day Turkey.[44] Ancient Egyptians used obsidian imported from the eastern Mediterranean and southern Red Sea regions. In the eastern Mediterranean area the material was used to make tools, mirrors and decorative objects.[45]

The use of obsidian tools was present in Japan near areas of volcanic activity.[46][47] Obsidian was mined during the Jōmon period.

Obsidian has also been found in Gilat, a site in the western Negev in Israel. Eight obsidian artifacts dating to the Chalcolithic Age found at this site were traced to obsidian sources in Anatolia. Neutron activation analysis (NAA) on the obsidian found at this site helped to reveal trade routes and exchange networks previously unknown.[48]

Americas

Obsidian mirrors were used by some Aztec priests to conjure visions and make prophecies. They were connected with Tezcatlipoca, god of obsidian and sorcery, whose name can be translated from the Nahuatl language as 'Smoking Mirror'.[43]

Indigenous people traded obsidian throughout the Americas. Each volcano and in some cases each volcanic eruption produces a distinguishable type of obsidian allowing archaeologists to use methods such as non-destructive energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence to select minor element compositions from both the artifact and geological sample to trace the origins of a particular artifact.[51] Similar tracing techniques have also allowed obsidian in Greece to be identified as coming from Milos, Nisyros or Gyali, islands in the Aegean Sea. Obsidian cores and blades were traded great distances inland from the coast.[52]

In Chile obsidian tools from

Oceania

The Lapita culture, active across a large area of the Pacific Ocean around 1000 BC, made widespread use of obsidian tools and engaged in long distance obsidian trading. The complexity of the production technique for these tools, and the care taken in their storage, may indicate that beyond their practical use they were associated with prestige or high status.[55]

Obsidian was also used on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) for edged tools such as Mataia and the pupils of the eyes of their Moai (statues), which were encircled by rings of bird bone.[56] Obsidian was used to inscribe the Rongorongo glyphs.

Current use

Obsidian can be used to make extremely sharp knives, and obsidian blades are a type of

The major disadvantage of obsidian blades is their brittleness compared to those made of metal,[62] thus limiting the surgical applications for obsidian blades to a variety of specialized uses where this is not a concern.[58]

Obsidian is also used for ornamental purposes and as a gemstone.[63] It presents a different appearance depending on how it is cut: in one direction it is jet black, while in another it is glistening gray. "Apache tears" are small rounded obsidian nuggets often embedded within a grayish-white perlite matrix.

Plinths for audio turntables have been made of obsidian since the 1970s, such as the grayish-black SH-10B3 plinth by Technics.

See also

- Apache tears – Popular term for pebbles of obsidian

- Helenite – Artificial glass made from volcanic ash

- basalticcomposition

- Knapping – Shaping of conchoidal fracturing stone to manufacture stone tools

- Libyan desert glass – Desert glass found in Libya and Egypt

- Mayor Island / Tūhua – New Zealand shield volcano – a source of Māori obsidian tools

- Obsidian hydration dating – Geochemical dating method

- Stone tool – Any tool, partially or entirely, made out of stone

- Vitrophyre – Glassy volcanic rock

- Yaxchilan Lintel 24 – Ancient Maya limestone carving from Yaxchilan in modern Chiapas, Mexico – Ancient carving showing a Maya bloodlet ritual involving a rope with obsidian shards.

References

- ^ King, Hobart M. "Obsidian". Geology.com. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-57506-042-2.

- .

- ^ Obsidian, Mindat.org

- ^ "obsidian". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ISBN 9781615304929.

- ISBN 0697001903.

- ISBN 978-0-521-42871-2. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ^ Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. III, p. 2 ("Obsidius").

- ^ obsidian. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Oxford University Press (1996). Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- ^ D Harper. obsidian. Etymology online. 2012-06-17

- ISBN 0816071055.

- ISBN 1441957030

- ISBN 978-1578591565.

- ISBN 978-1586034245.

- S2CID 163772761.

- .

- JSTOR 24960359.

- ISBN 9781941451045.

- ISBN 978-1-4398-0306-6.

- .

- ^ "Perlite – Mineral Deposit Profiles". B.C. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ^ hdl:10174/9676. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ Nadin, E. (2007). "The secret lives of minerals" (PDF). Engineering & Science (1): 10–20.

- .

- ^ Washington Obsidian Source Map Archived 2015-08-21 at the Wayback Machine. Obsidianlab.com. Retrieved on 2011-11-20.

- ^ Oregon Obsidian Sources. Sourcecatalog.com (2011-11-15). Retrieved on 2011-11-20.

- ISBN 0521119901.

- ^

E Blake; A B Knapp (2005). The Archaeology Of Mediterranean Prehistory. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0631232681.

- ISBN 3447033959.

- ISBN 3447062177.

- ISBN 1575060426.

- ^ Bunny, Sarah (18 April 1985). "Ancient trade routes for obsidian". New Scientist.

- ISBN 0890030316.

- ISBN 1931707057.

- ISBN 0521215927

- ^ National Museum of Kenya. Kariandusi Archived 2007-10-24 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2012-06-30

- S2CID 150094926.

- S2CID 134356403.

- ISBN 978-0854042623.

- S2CID 3803714.

- ^ Tripković, Boban (2003). "The Quality and Value In Neolithic Europe: An Alternative View on Obsidian Artifacts". South Eastern Europe Proceedings of the ESF Workshop, Sofia. 103: 119–123. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ a b "John Dee's spirit mirror – The British Library". 2020-04-01. Archived from the original on 2020-04-01. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ John Noble Wilford (2010-04-05). "In Syria, a Prologue for Cities". The New York Times.

- ISBN 978-3540425793.

- ^ "Obsidian | Oki Islands UNESCO Global Geopark".

- doi:10.7152/bippa.v27i0.11982 (inactive 31 January 2024). Retrieved 2 March 2022.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link - .

- ^ Brokmann, Carlos (2000). "Tipología y análisis de la obsidiana de Yaxchilán, Chiapas". Colección Científica (in Spanish) (422). INAH.

- ^ Hogan, CM (2008). A. Burnham (ed.). "Morro Creek". Megalithic.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- ^ Panich, Lee; Michelini, Antonio; Shackley, M. (2012-12-01). "Obsidian Sources of Northern Baja California: The Known and the Unknown". Faculty Publications.

- ISSN 0278-4165.

- .

- OCLC 61022562.

- ISBN 978-0-19-992507-0.

- ISBN 978-1-58839-011-0.

- ^ Shadbolt, Peter (2015-04-02). "CNN Health: How Stone Age blades are still cutting it in modern surgery". CNN. Retrieved 2023-09-07.

- ^ PMID 7046256.

- ISBN 9780495810841. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- PMID 8415970.

- ^ Fine Science Tools (FST). "FST product catalog". FST. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ "Fine Science Tools – Obsidian Scalpels" https://www.finescience.com/en-US/Products/Scalpels-Blades/Micro-Knives/Obsidian-Scalpels

- ISBN 9783662042885.