Ogata Kōrin

This article contains too many pictures for its overall length. |

Ogata Kōrin | |

|---|---|

| 尾形 光琳 | |

| Born | 1658 |

| Died | June 2, 1716 (aged 57–58) Kyoto, Tokugawa shogunate |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Known for |

|

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | Rinpa school |

Ogata Kōrin (

Kōrin is best known for his byōbu folding screens, such as Irises[3] and Red and White Plum Blossoms[4] (both registered National Treasures), and his paintings on ceramics and lacquerware[1] produced by his brother Kenzan (1663–1743). Also a prolific designer, he worked with a variety of decorative and practical objects, such as round fans, makie writing boxes or inrō medicine cases.

He is also credited

Biography

Kōrin was born in Kyoto into a wealthy merchant family, dedicated to the design and sale of fine textiles.[8] The family business, named Karigane-ya, catered to the aristocratic women of the city.[9] His father, Ogata Sōken (1621–1687), who was a noted calligrapher in the style of Kōetsu and patron of Noh theater,[9] introduced his sons to the arts.[10] Kōrin was the second son of Sōken. His younger brother Kenzan was a celebrated potter and painter in his own right, with whom he collaborated frequently.[1] Kōrin studied under Yamamoto Soken (active ca. 1683–1706) of the Kanō school,[2] Kano Tsunenobu (1636–1713) and Sumiyoshi Gukei (1631–1705), but his biggest influences were his predecessors Hon'ami Kōetsu and Tawaraya Sōtatsu.[10]

Sōken died in 1687,[9] and the elder brother took over the family business, leaving Kōrin and Kenzan free to enjoy a considerable inheritance. After this, Kōrin led a very active social life, but his spending ran him into financial difficulties the following years, partly due to loans made to feudal lords.[11] This forced him to pawn some of his treasured possessions. A letter sent by him to a pawnbroker in 1694 regarding "one writing box with deer by Kōetsu" and "one Shigaraki ware water jar with lacquer lid" survives.[12]

Kōrin established himself as an artist only late in life.[13] In 1701, he was awarded the honorific title of hokkyō[14] ("Bridge of the Dharma"), the third highest rank awarded to Buddhist artists, and in 1704 he moved to Edo,[15][16] where lucrative commissions were more readily available. His early masterpieces, such as his Irises are generally dated to this period.[3] During this time, he also had the opportunity to study the ink paintings of medieval monk painters Sesshū Tōyō (1420–1506) and Sesson Shukei (c. 1504 – c. 1589).[15] These are seen as important influences in his work from that period, the Rough Waves painting for example.[15]

In 1709, he moved back to Kyoto.[15][16] He built a house with an atelier on Shinmachi street in 1712 and lived there the last five years of his life.[17][14] His masterpieces from that last period, such as the Red and White Plum Blossoms screens, are thought to have been painted there.[17]

Kōrin died famous but impoverished[14] on June 2, 1716,[10] at the age of 59. His grave is located at the Myōken-ji temple in Kyoto.[18] His chief pupils were Tatebayashi Kagei, Watanabe Shikō[10] and Fukae Rōshu,[2] but the present knowledge and appreciation of his work are largely due to the early efforts of his brother Kenzan[19] and later Sakai Hōitsu, who brought about a revival of Kōrin's style.[10]

Works

Irises (紙本金地著色燕子花図) is a pair of six-panel byōbu folding screens made circa 1701–1705,[20][3] using ink and color on gold-foiled paper.[21] The screens are among the first works of Kōrin as a hokkyō. It depicts abstracted blue Japanese irises in bloom, and their green foliage, creating a rhythmically repeating but varying pattern across the panels. The similarities of some blooms indicate that a stencil was used.[3] The work shows influence of Tawaraya, and it is representative of the Rinpa school. It is inspired by an episode in the Heian-period text The Tales of Ise.

- Irises

Each screen measures 150.9 by 338.8 centimetres (59.4 in × 133.4 in). They were probably made for the Nijō family, and were presented to the

Kōrin made a similar work about five[23] to twelve[24] years later, another pair of six-panel screens, known as Irises at Yatsuhashi (八橋図屏風). It is a more explicit reference to the "Yatsuhashi (Eight Bridges)" episode from The Tales of Ise, including the depiction of an angular bridge that sweeps diagonally across both screens.[23]

The screens were made using ink and color on gold-foiled paper and measure 163.7 by 352.4 centimetres (64.4 in × 138.7 in) each. They have been held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City since 1953, and were last displayed in 2013.[24]

Both Irises screens were displayed together for the first time in almost a century[24] in 2012 at the "Korin: National Treasure Irises of the Nezu Museum and Eight-Bridge of the Metropolitan Museum of Art" exhibition at the Nezu Museum.[23]

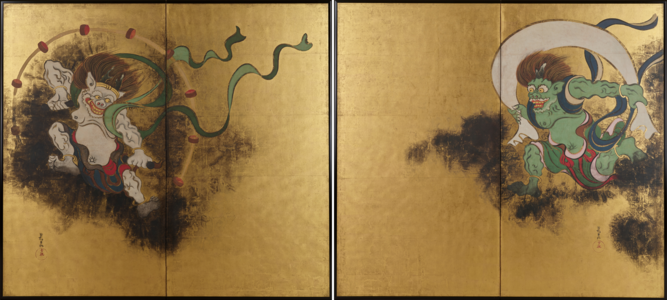

Wind God and Thunder God (紙本金地著色風神雷神図) is a pair of two-folded screens[25] made using ink and color on gold-foiled paper.[26] It is a replica of an original work by Tawaraya which depicts Raijin, the god of lightning, thunder and storms in the Shinto religion and in Japanese mythology, and Fūjin, the god of wind. Later, Sakai Hōitsu, another prominent member of the Rinpa school, painted his own version of the work. All three versions of the work were displayed together for the first time in seventy-five years in 2015, at the Kyoto National Museum exhibition Rinpa: The Aesthetics of the Capital.[18]

- Wind God and Thunder God

-

Kōrin's version

-

Sōtatsu's original

The screens measure 421.6 by 464.8 centimetres (166 in × 183 in) each.[25] At some point Hōitsu owned them, and in fact he painted one of his most famous works, Flowering Plants of Summer and Autumn, in the back of these screens. The monumental two-sided byōbu screens became a symbol of the Rinpa tradition, but both sides of the screens have since been separated to protect them from damage.[26] They are now part of the collection of the Tokyo National Museum, where they are exhibited occasionally. They are listed as an Important Cultural Property.[25]

Red and White Plum Blossoms (紙本金地著色紅白梅図) is a pair of two-panel byōbu folding screens painted by Kōrin using ink and color on gold-foiled paper.[13] A late masterpiece, completed probably circa 1712–1716 in his atelier in Kyoto,[17] it is considered his crowning achievement.[27] The simple, stylized composition of the work[28] depicts a patterned flowing river with a white plum tree on the left and a red plum tree on the right.[29] The plum blossoms indicate the scene occurs in spring.[30]

No documentation exists from before the 20th century on the commission or provenance of the screens.[31] They receive mention in no Edo-period publications on Kōrin's works and were not copied by his followers, which suggests they were not well known. A journal article in 1907[a] is the first known publication about them, and their first public display came in a 200th-anniversary exhibition of Kōrin's work in 1915.[32]

In addition to the use of tarashikomi, the work is notable for its plum flowers depicted using pigment only, without any outline, now a popular technique known as Kōrin Plum Flowers.[27]

- Red and White Plum Blossoms

Each screen measures 156.5 × 172.5 centimetres (61.6 × 67.9 in). Red and White Plum Blossoms belonged for a long time to the Tsugaru clan, but were purchased by Mokichi Okada in the mid-1950s.[31] Along with the rest of Okada's collection,[33] it is now owned by the MOA Museum of Art in Atami, where they are displayed for one month per year in late winter, the season when the plum blossoms bloom. It is listed as a National Treasure of Japan.

Sometime in the early 18th century, Kōrin painted a notable copy of

Gallery

-

Cranes, Pines, and Bamboo

-

Autumn Grasses

-

Black Pines and Maple Tree (Important Cultural Property)

-

The Poet Bo Juyi

-

Waves at Matsushima

-

Cranes

-

Cranes

-

Cranes, Pines, and Bamboo

-

Tai Gong Wang(Important Cultural Property)

-

Ducks and Snow-Covered Pine Trees

-

The Thirty-Six Immortal Poets (Important Art Object)

-

Rough Waves

-

Bamboo and plum tree (Important Cultural Property)

-

Flowering Plants in Autumn

- Hanging scrolls

-

Portrait of Nakamura Kuranosuke (Important Cultural Property)

-

The Empress Akikonomu

-

The Tales of Ise, Yatsuhashi

-

The Immortal Qin Qao

-

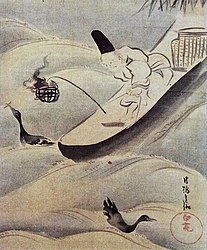

Cormorant Fishing

-

Tiger and Bamboo

-

Hotei

- Crafts

-

Square dish, design of poet watching wild geese (Important Cultural Property)

-

Square dish with courtier gazing at a waterfall

Notes

- ^ 「尾形光琳筆 梅花図屏風に就て」 "Ogata Kōrin hitsu Baika Zu Byōbu ni tsuite", in Kokka (『國華』), issue 201, p. 569 (1907)

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Nezu Museum 2015, p. vii.

- ^ a b c Nussbaum & Roth 2005, p. 561.

- ^ a b c d "Irises". Columbia University. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- ^ Hayakawa et al. 2007, p. 57.

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art 2000, p. 189.

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art 2000, p. 310.

- ^ Carpenter 2012, p. 26.

- ^ Nezu Museum 2015, p. v.

- ^ a b c "33. Ogata Korin (1658–1716) 尾形光琳". kaikodo. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Strange, Edward Fairbrother (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 913.

- ^ Pekarik 1980, p. 57.

- ^ Pekarik 1980, pp. 57–59.

- ^ a b Nezu Museum 2015, p. iv.

- ^ a b c Pekarik 1980, p. 59.

- ^ a b c d Carpenter 2012, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Metropolitan Museum of Art 2000, p. 312.

- ^ a b c "Korin's Residence (reconstructed)". MOA Museum of Art. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "RINPA: The Aesthetics of the Capital". Kyoto National Museum. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ Carpenter 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Daugherty 2003, p. 42.

- ^ a b "Irises". Nezu Museum. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- ^ "Special Exhibition: Irises and Mountain Stream in Summer and Autumn". Nezu Museum. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Irises at Yatsuhashi (Eight Bridges)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c "National Treasure Irises of the Nezu Museum and Eight-Bridge of the Metropolitan Museum of Art". Nezu Museum. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Wind God and Thunder God". Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b "Wind God and Thunder God". National Institutes for Cultural Heritage. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b "Red and White Plum Blossoms". MOA Museum of Art. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ Carpenter 2012, p. 146.

- ^ Hayakawa et al. 2007, p. 58.

- ^ Nikoru 1997, p. 291.

- ^ a b Daugherty 2003, p. 39.

- ^ Daugherty 2003, p. 43.

- ^ Daugherty 2003, pp. 39–40.

- ^ "Waves of Matsushima". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

Sources

- Carpenter, John T. (2012). Designing Nature: The Rinpa Aesthetic in Japanese Art. New York: ISBN 978-1-58839-471-2.

- Randall, Doanda. (1960). Kōrin. New York: Crown. OCLC 1487440

- Pekarik, Andrew (1980). Japanese Lacquer, 1600–1900. New York: ISBN 978-0-87099-247-6.

- Nikoru, C. W. (1997). Japan: The Cycle of Life. ISBN 978-4-7700-2088-8.

- Bridge of Dreams: the Mary Griggs Burke collection of Japanese art (PDF), Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, 2000

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric; Roth, Käthe (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Cambridge: OCLC 58053128.

- Daugherty, Cynthia (March 2003). "Historiography and Iconography in Ogata Korin's Iris and Plum Screens" (PDF). Ningen Kagaku Hen (16). Kyushu Institute of Technology: 39–91. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 23, 2016.

- Hayakawa, Yasuhiro; Shirono, Seiji; Miura, Sadatoshi; Matsushima, Tomohide; Uchida, Tokugo (2007). "Non-Destructive Analysis of a Painting, National Treasure in Japan" (PDF). Advances in X-ray Analysis. 50. JCPDS-International Centre for Diffraction Data: 57–63. ISSN 1097-0002. Archived from the original(PDF) on December 20, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Irises and Red and White Plum Blossoms. Secret of Korin's Designs, Nezu Museum, 2015

External links

Media related to Ogata Korin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ogata Korin at Wikimedia Commons

![Writing Box with Eight Bridges [ja] (National Treasure)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/62/WritingBox_EightBridges_OgataKorin.JPG/250px-WritingBox_EightBridges_OgataKorin.JPG)