Opioid

| Opioid | |

|---|---|

N02A | |

| Mode of action | Opioid receptor |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D000701 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Opioids are a class of drugs that derive from, or mimic, natural substances found in the opium poppy plant. Opioids work in the brain to produce a variety of effects, including pain relief. As a class of substances, they act on opioid receptors to produce morphine-like effects.[2][3]

The terms 'opioid' and 'opiate' are sometimes used interchangeably, but there are key differences based on the manufacturing processes of these medications.[4]

Medically they are primarily used for

Side effects of opioids may include

Opioids act by binding to opioid receptors, which are found principally in the central and peripheral nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract. These receptors mediate both the psychoactive and the somatic effects of opioids. Opioid drugs include partial agonists, like the anti-diarrhea drug loperamide and antagonists like naloxegol for opioid-induced constipation, which do not cross the blood–brain barrier, but can displace other opioids from binding to those receptors in the myenteric plexus.

Because opioids are addictive and may result in fatal overdose, most are controlled substances. In 2013, between 28 and 38 million people used opioids illicitly (0.6% to 0.8% of the global population between the ages of 15 and 65).[12] In 2011, an estimated 4 million people in the United States used opioids recreationally or were dependent on them.[13] As of 2015, increased rates of recreational use and addiction are attributed to over-prescription of opioid medications and inexpensive illicit heroin.[14][15][16] Conversely, fears about overprescribing, exaggerated side effects, and addiction from opioids are similarly blamed for under-treatment of pain.[17][18]

Terminology

Opioids include opiates, an older term that refers to such drugs derived from opium, including morphine itself.[19] Other opioids are semi-synthetic and synthetic drugs such as hydrocodone, oxycodone and fentanyl; antagonist drugs such as naloxone; and endogenous peptides such as endorphins.[20] The terms opiate and narcotic are sometimes encountered as synonyms for opioid. Opiate is properly limited to the natural alkaloids found in the resin of the opium poppy although some include semi-synthetic derivatives.[19][21] Narcotic, derived from words meaning 'numbness' or 'sleep', as an American legal term, refers to cocaine and opioids, and their source materials; it is also loosely applied to any illegal or controlled psychoactive drug.[22][23] In some jurisdictions all controlled drugs are legally classified as narcotics. The term can have pejorative connotations and its use is generally discouraged where that is the case.[24][25]

Medical uses

Pain

The weak opioid codeine, in low doses and combined with one or more other drugs, is commonly available in prescription medicines and without a prescription to treat mild pain.[26][27][28] Other opioids are usually reserved for the relief of moderate to severe pain.[27]

Acute pain

Opioids are effective for the treatment of acute pain (such as pain following surgery).[29] For immediate relief of moderate to severe acute pain, opioids are frequently the treatment of choice due to their rapid onset, efficacy and reduced risk of dependence. However, a new report showed a clear risk of prolonged opioid use when opioid analgesics are initiated for an acute pain management following surgery or trauma.[30] They have also been found to be important in palliative care to help with the severe, chronic, disabling pain that may occur in some terminal conditions such as cancer, and degenerative conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis. In many cases opioids are a successful long-term care strategy for those with chronic cancer pain.

Just over half of all states in the US have enacted laws that restrict the prescribing or dispensing of opioids for acute pain.[31]

Chronic non-cancer pain

Guidelines have suggested that the risk of opioids is likely greater than their benefits when used for most non-cancer chronic conditions including

In treating chronic pain, opioids are an option to be tried after other less risky pain relievers have been considered, including paracetamol/acetaminophen or NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen.[35] Some types of chronic pain, including the pain caused by fibromyalgia or migraine, are preferentially treated with drugs other than opioids.[36][37] The efficacy of using opioids to lessen chronic neuropathic pain is uncertain.[38]

Opioids are contraindicated as a first-line treatment for headache because they impair alertness, bring risk of dependence, and increase the risk that episodic headaches will become chronic.[39] Opioids can also cause heightened sensitivity to headache pain.[39] When other treatments fail or are unavailable, opioids may be appropriate for treating headache if the patient can be monitored to prevent the development of chronic headache.[39]

Opioids are being used more frequently in the management of non-malignant

Other

Cough

Codeine was once viewed as the "gold standard" in cough suppressants, but this position is now questioned.[47] Some recent placebo-controlled trials have found that it may be no better than a placebo for some causes including acute cough in children.[48][49] as a consequence, it is not recommended for children.[49] Additionally, there is no evidence that hydrocodone is useful in children.[50] Similarly, a 2012 Dutch guideline regarding the treatment of acute cough does not recommend its use.[51] (The opioid analogue dextromethorphan, long claimed to be as effective a cough suppressant as codeine,[52] has similarly demonstrated little benefit in several recent studies.[53])

Low dose morphine may help chronic cough but its use is limited by side effects.[54]

Diarrhea

In cases of diarrhea-predominate

The ability to suppress diarrhea also produces constipation when opioids are used beyond several weeks.[55] Naloxegol, a peripherally-selective opioid antagonist is now available to treat opioid induced constipation.[56]

Shortness of breath

Opioids may help with

Restless legs syndrome

Though not typically a first line of treatment, opioids, such as oxycodone and methadone, are sometimes used in the treatment of severe and refractory restless legs syndrome.[61]

Hyperalgesia

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) has been evident in patients after chronic opioid exposure.[62][63]

Adverse effects

Common and short term

Other

- Cognitive effects

- Dizziness

- Loss of appetite

- Delayed gastric emptying

- Decreased sex drive

- Impaired sexual function

- Decreased testosterone levels

- Depression

- Immunodeficiency

- Increased pain sensitivity

- Irregular menstruation

- Increased risk of falls

- Slowed breathing

- Coma

Each year 69,000 people worldwide die of opioid overdose, and 15 million people have an opioid addiction.[65]

In older adults, opioid use is associated with increased adverse effects such as "sedation, nausea, vomiting, constipation, urinary retention, and falls".[66] As a result, older adults taking opioids are at greater risk for injury.[67] Opioids do not cause any specific organ toxicity, unlike many other drugs, such as aspirin and paracetamol. They are not associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and kidney toxicity.[68]

Prescription of opioids for acute low back pain and management of osteoarthritis seem to have long-term adverse effects[69][70]

According to the USCDC, methadone was involved in 31% of opioid related deaths in the US between 1999–2010 and 40% as the sole drug involved, far higher than other opioids.[71] Studies of long term opioids have found that many stop them, and that minor side effects were common.[72] Addiction occurred in about 0.3%.[72] In the United States in 2016 opioid overdose resulted in the death of 1.7 in 10,000 people.[73]

Reinforcement disorders

Tolerance

Tolerance is a process characterized by neuroadaptations that result in reduced drug effects. While receptor upregulation may often play an important role other mechanisms are also known.[74] Tolerance is more pronounced for some effects than for others; tolerance occurs slowly to the effects on mood, itching, urinary retention, and respiratory depression, but occurs more quickly to the analgesia and other physical side effects. However, tolerance does not develop to constipation or miosis (the constriction of the pupil of the eye to less than or equal to two millimeters). This idea has been challenged, however, with some authors arguing that tolerance does develop to miosis.[75]

Tolerance to opioids is attenuated by a number of substances, including:

- calcium channel blockers[76][77][78]

- cholecystokinin antagonists, such as proglumide[84][85][86]

- Newer agents such as the phosphodiesterase inhibitor ibudilast have also been researched for this application.[87]

Tolerance is a physiologic process where the body adjusts to a medication that is frequently present, usually requiring higher doses of the same medication over time to achieve the same effect. It is a common occurrence in individuals taking high doses of opioids for extended periods, but does not predict any relationship to misuse or addiction.

Physical dependence

Physical dependence is the physiological adaptation of the body to the presence of a substance, in this case opioid medication. It is defined by the development of withdrawal symptoms when the substance is discontinued, when the dose is reduced abruptly or, specifically in the case of opioids, when an antagonist (e.g., naloxone) or an agonist-antagonist (e.g., pentazocine) is administered. Physical dependence is a normal and expected aspect of certain medications and does not necessarily imply that the patient is addicted.

The withdrawal symptoms for opiates may include severe

Critical patients who received regular doses of opioids experience iatrogenic withdrawal as a frequent syndrome.[91]

Addiction

In European nations such as Austria, Bulgaria, and Slovakia, slow-release oral morphine formulations are used in opiate substitution therapy (OST) for patients who do not well tolerate the side effects of buprenorphine or methadone. Buprenorphine can also be used together with naloxone for a longer treatment of addiction. In other European countries including the UK, this is also legally used for OST although on a varying scale of acceptance.

Slow-release formulations of medications are intended to curb misuse and lower addiction rates while trying to still provide legitimate pain relief and ease of use to pain patients. Questions remain, however, about the efficacy and safety of these types of preparations. Further tamper resistant medications are currently under consideration with trials for market approval by the FDA.[92][93]

The amount of evidence available only permits making a weak conclusion, but it suggests that a physician properly managing opioid use in patients with no history of substance use disorder can give long-term pain relief with little risk of developing addiction, or other serious side effects.[72]

Problems with opioids include the following:

- Some people find that opioids do not relieve all of their pain.[94]

- Some people find that opioids side effects cause problems which outweigh the therapy's benefit.[72]

- Some people build tolerance to opioids over time. This requires them to increase their drug dosage to maintain the benefit, and that in turn also increases the unwanted side effects.[72]

- Long-term opioid use can cause opioid-induced hyperalgesia, which is a condition in which the patient has increased sensitivity to pain.[95]

All of the opioids can cause side effects.

Nausea and vomiting

Tolerance to nausea occurs within 7–10 days, during which antiemetics (e.g. low dose haloperidol once at night) are very effective.[citation needed] Due to severe side effects such as tardive dyskinesia, haloperidol is now rarely used. A related drug, prochlorperazine is more often used, although it has similar risks. Stronger antiemetics such as ondansetron or tropisetron are sometimes used when nausea is severe or continuous and disturbing, despite their greater cost. A less expensive alternative is dopamine antagonists such as domperidone and metoclopramide. Domperidone does not cross the blood–brain barrier and produce adverse central antidopaminergic effects, but blocks opioid emetic action in the chemoreceptor trigger zone. This drug is not available in the U.S.

Some antihistamines with anticholinergic properties (e.g. orphenadrine, diphenhydramine) may also be effective. The first-generation antihistamine hydroxyzine is very commonly used, with the added advantages of not causing movement disorders, and also possessing analgesic-sparing properties. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol relieves nausea and vomiting;[96][97] it also produces analgesia that may allow lower doses of opioids with reduced nausea and vomiting.[98][99]

- 5-HT3 antagonists (e.g. ondansetron)

- Dopamine antagonists (e.g. domperidone)

- Anti-cholinergic antihistamines (e.g. diphenhydramine)

- Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (e.g. dronabinol)

Vomiting is due to gastric stasis (large volume vomiting, brief nausea relieved by vomiting, oesophageal reflux, epigastric fullness, early satiation), besides direct action on the chemoreceptor trigger zone of the area postrema, the vomiting centre of the brain. Vomiting can thus be prevented by prokinetic agents (e.g. domperidone or metoclopramide). If vomiting has already started, these drugs need to be administered by a non-oral route (e.g. subcutaneous for metoclopramide, rectally for domperidone).

- Prokinetic agents (e.g. domperidone)

- Anti-cholinergic agents (e.g. orphenadrine)

Evidence suggests that opioid-inclusive anaesthesia is associated with postoperative nausea and vomiting.[100]

Patients with chronic pain using opioids had small improvements in pain and physically functioning and increased risk of vomiting.[101]

Drowsiness

Tolerance to

- Stimulants (e.g. caffeine, modafinil, amphetamine, methylphenidate)

Itching

), and these may also reduce opioid induced nausea.- Antihistamines (e.g. fexofenadine)

Constipation

Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) develops in 90 to 95% of people taking opioids long-term.[104] Since tolerance to this problem does not generally develop, most people on long-term opioids need to take a laxative or enemas.[105]

Treatment of OIC is successional and dependent on severity.

If laxatives are insufficiently effective (which is often the case),

Opioid rotation is one method suggested to minimise the impact of constipation in long-term users.[114] While all opioids cause constipation, there are some differences between drugs, with studies suggesting tramadol, tapentadol, methadone and fentanyl may cause relatively less constipation, while with codeine, morphine, oxycodone or hydromorphone constipation may be comparatively more severe.

Respiratory depression

]- Respiratory stimulants: 5-HT4 agonists (e.g. BIMU8), δ-opioid agonists (e.g. BW373U86) and AMPAkines (e.g. CX717) can all reduce respiratory depression caused by opioids without affecting analgesia, but most of these drugs are only moderately effective or have side effects which preclude use in humans. 5-HT1A agonists such as 8-OH-DPAT and repinotanalso counteract opioid-induced respiratory depression, but at the same time reduce analgesia, which limits their usefulness for this application.

- Opioid antagonists (e.g. naloxone, nalmefene, diprenorphine)

The initial 24 hours after opioid administration appear to be the most critical with regard to life-threatening OIRD, but may be preventable with a more cautious approach to opioid use.[120]

Patients with cardiac, respiratory disease and/or obstructive sleep apnoea are at increased risk for OIRD.[121]

Increased pain sensitivity

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia – where individuals using opioids to relieve pain

Side effects such as hyperalgesia and allodynia, sometimes accompanied by a worsening of neuropathic pain, may be consequences of long-term treatment with opioid analgesics, especially when increasing tolerance has resulted in loss of efficacy and consequent progressive dose escalation over time. This appears to largely be a result of actions of opioid drugs at targets other than the three classic opioid receptors, including the nociceptin receptor, sigma receptor and Toll-like receptor 4, and can be counteracted in animal models by antagonists at these targets such as J-113,397, BD-1047 or (+)-naloxone respectively.[128] No drugs are currently approved specifically for counteracting opioid-induced hyperalgesia in humans and in severe cases the only solution may be to discontinue use of opioid analgesics and replace them with non-opioid analgesic drugs. However, since individual sensitivity to the development of this side effect is highly dose dependent and may vary depending which opioid analgesic is used, many patients can avoid this side effect simply through dose reduction of the opioid drug (usually accompanied by the addition of a supplemental non-opioid analgesic), rotating between different opioid drugs, or by switching to a milder opioid with a mixed mode of action that also counteracts neuropathic pain, particularly tramadol or tapentadol.[129][130][131]

- NMDA receptor antagonists such as ketamine

- SNRIs such as milnacipran

- Anticonvulsants such as gabapentin or pregabalin

Other adverse effects

Low sex hormone levels

Clinical studies have consistently associated medical and recreational opioid use with

Disruption of work

Use of opioids may be a risk factor for failing to return to work.[138][139]

Persons performing any safety-sensitive task should not use opioids.

People who take opioids long term have increased likelihood of being unemployed.[141] Taking opioids may further disrupt the patient's life and the adverse effects of opioids themselves can become a significant barrier to patients having an active life, gaining employment, and sustaining a career.

In addition, lack of employment may be a predictor of aberrant use of prescription opioids.[142]

Increased accident-proneness

Opioid use may increase

Reduced Attention

Opioids have been shown to reduce attention, more so when used with antidepressants and/or anticonvulsants.[146]

Rare side effects

Infrequent adverse reactions in patients taking opioids for pain relief include: dose-related respiratory depression (especially with more

Pregnancy

Opioid use during pregnancy can have significant implications for both the mother and the developing fetus.

Interactions

Physicians treating patients using opioids in combination with other drugs keep continual documentation that further treatment is indicated and remain aware of opportunities to adjust treatment if the patient's condition changes to merit less risky therapy.[147]

With other depressant drugs

The concurrent use of opioids with other depressant drugs such as

Opioid antagonist

Opioid effects (adverse or otherwise) can be reversed with an opioid antagonist such as

Naltrexone does not appear to increase risk of serious adverse events, which confirms the safety of oral naltrexone.[152] Mortality or serious adverse events due to rebound toxicity in patients with naloxone were rare.[153]

Pharmacology

| Drug | Relative Potency [154] |

Nonionized Fraction |

Protein Binding |

Lipid Solubility [155][156][157] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphine | 1 | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Pethidine (meperidine) | 0.1 | + | +++ | +++ |

| Hydromorphone | 10 | + | +++ | |

| Alfentanil | 10–25 | ++++ | ++++ | +++ |

| Fentanyl | 50–100[158][159][160] | + | +++ | ++++ |

| Remifentanil | 250[citation needed] | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Sufentanil | 500–1000 | ++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| Etorphine | 1000–3000 | |||

| Carfentanil | 10000 |

Opioids bind to specific

The

Functional selectivity

A new strategy of drug development takes receptor signal transduction into consideration. This strategy strives to increase the activation of desirable signalling pathways while reducing the impact on undesirable pathways. This differential strategy has been given several names, including functional selectivity and biased agonism. The first opioid that was intentionally designed as a biased agonist and placed into clinical evaluation is the drug oliceridine. It displays analgesic activity and reduced adverse effects.[162]

Opioid comparison

Extensive research has been conducted to determine equivalence ratios comparing the relative potency of opioids. Given a dose of an opioid, an equianalgesic table is used to find the equivalent dosage of another. Such tables are used in opioid rotation practices, and to describe an opioid by comparison to morphine, the reference opioid. Equianalgesic tables typically list drug half-lives, and sometimes equianalgesic doses of the same drug by means of administration, such as morphine: oral and intravenous.

Binding profiles

| Compound | MOR |

DOR |

KOR |

Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-HO-PCP | 60 | 2,300 | 140 | [163] | |

| 7-Hydroxymitragynine | 13.5 | 155 | 123 | [164] | |

β-Chlornaltrexamine |

0.90 | 115 | 0.083 | [165] | |

| β-Endorphin | 1.0 | 1.0 | 52 | [165] | |

β-Funaltrexamine |

0.33 | 48 | 2.8 | [165] | |

| (+)-cis-3-methylfentanyl | 0.24 | ND | ND | [166] | |

| Alazocine | 2.7 | 4.1 | 3.2 | [167] | |

(−)-Alazocine |

3.0 | 15 | 4.7 | [168] | |

(+)-Alazocine |

1,900 | 19,000 | 1,600 | [168] | |

| Alfentanil | 39 | 21,200 | ND | [169] | |

| Binaltorphimine | 1.3 | 5.8 | 0.79 | [169] | |

| BNTX | 18 | 0.66 | 55 | [165] | |

| Bremazocine | 0.75 | 2.3 | 0.089 | [165] | |

| (−)-Bremazocine | 0.62 | 0.78 | 0.075 | [169] | |

| Buprenorphine | 4.18 | 25.8 | 12.9 | [170] | |

| Butorphanol | 1.7 | 13 | 7.4 | [168] | |

| BW-3734 | 26 | 0.013 | 17 | [165] | |

| Carfentanil | 0.024 | 3.3 | 43 | [167] | |

| Cebranopadol | 0.7 | 18 | 2.6 | [171] | |

| Codeine | 79 | >1,000 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| CTOP | 0.18 | >1,000 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| Cyclazocine | 0.45 | 6.3 | 5.9 | [168] | |

| Cyprodime | 9.4 | 356 | 176 | [169] | |

| DADLE | 16 | 0.74 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| DAMGO | 2.0 | >1,000 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| [D-Ala2]Deltorphin II | >1,000 | 3.3 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| Dermorphin | 0.33 | >1,000 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| (+)-Desmetramadol (O-DSMT) | 17 | 690 | 1,800 | [172][173] | |

| Dextropropoxyphene | 34.5 | 380 | 1,220 | [170] | |

| Dezocine | 3.6 | 290 | 460 | [167] | |

| Dihydroetorphine | 0.45 | 1.82 | 0.57 | [174] | |

| Dihydromorphine | 2.5 | 137 | 223 | [175] | |

| Diprenorphine | 0.072 | 0.23 | 0.017 | [165] | |

| DPDPE | >1,000 | 14 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| DSLET | 39 | 4.8 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| Dynorphin A | 32 | >1,000 | 0.5 | [165] | |

| Ethylketazocine | 3.1 | 101 | 0.40 | [165] | |

| (−)-Ethylketazocine | 2.3 | 5.2 | 2.2 | [168] | |

| (+)-Ethylketazocine | 2,500 | >10,000 | 1,600 | [168] | |

| Etorphine | 0.23 | 1.4 | 0.13 | [165] | |

| Fentanyl | 0.39 | >1,000 | 255 | [165] | |

| Hydrocodone | 11.1 | 962 | 501 | [170] | |

| Hydromorphone | 0.47 | 18.5 | 24.9 | [167] | |

| ICI-204488 | >1,000 | >1,000 | 0.71 | [165] | |

| Leu-enkephalin | 3.4 | 4.0 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| Levacetylmethadol | 9.86 | 169 | 1,020 | [170] | |

| Lofentanil | 0.68 | 5.5 | 5.9 | [165] | |

| Met-enkephalin | 0.65 | 1.7 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| Metazocine | 3.8 | 44.3 | 13.3 | [167] | |

| Methadone | 1.7 | 435 | 405 | [170] | |

Dextromethadone |

19.7 | 960 | 1,370 | [170] | |

| Levomethadone | 0.945 | 371 | 1,860 | [170] | |

| Methallorphan | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Dextrallorphan | 1,140 | 2,660 | 34.6 | [170] | |

| Levallorphan | 0.213 | 2.18 | 1,100 | [170] | |

| Methorphan | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Dextromethorphan | 1,280 | 11,500 | 7,000 | [170] | |

| Levomethorphan | 11.2 | 249 | 225 | [170] | |

| Mitragynine | 7.24 | 60.3 | 1,100 | [164] | |

| Mitragynine pseudoindoxyl | 0.087 | 3.02 | 79.4 | [164] | |

Morphanol |

ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Dextrorphan | 420 | 34,700 | 5,950 | [170] | |

| Levorphanol | 0.42 | 3.61 | 4.2 | [170] | |

| Morphiceptin | 56 | >1,000 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| Morphine | 1.8 | 90 | 317 | [169] | |

| Morphine, (−)- | 1.24 | 145 | 23.4 | [170] | |

| Morphine, (+)- | >10,000 | >100,000 | >300,000 | [170] | |

| MR-2266 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.16 | [167] | |

| Nalbuphine | 11 | >1,000 | 3.9 | [165] | |

| Nalmefene | 0.24 | 16 | 0.083 | [176] | |

| Nalorphine | 0.97 | 148 | 1.1 | [165] | |

| Naloxonazine | 0.054 | 8.6 | 11 | [165] | |

| Naloxone | 1.1 | 16 | 12 | [168] | |

| (−)-Naloxone | 0.93 | 17 | 2.3 | [165] | |

| (+)-Naloxone | >1,000 | >1,000 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| Naltrexone | 1.0 | 149 | 3.9 | [165] | |

| Naltriben | 12 | 0.013 | 13 | [165] | |

| Naltrindole | 64 | 0.02 | 66 | [165] | |

| Norbinaltorphimine | 2.2 | 65 | 0.027 | [165] | |

| Normorphine | 4.0 | 310 | 149 | [169] | |

| Ohmefentanyl | 0.0079 | 10 | 32 | [169] | |

| Oxycodone | 8.69 | 901 | 1,350 | [170] | |

| Oxymorphindole | 111 | 0.7 | 228 | [167] | |

| Oxymorphone | 0.78 | 50 | 137 | [169] | |

| Pentazocine | 5.7 | 31 | 7.2 | [165] | |

| Pethidine (meperidine) | 385 | 4,350 | 5,140 | [169] | |

| Phenazocine | 0.20 | 5.0 | 2.0 | [177] | |

PLO17 |

30 | >1,000 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| Quadazocine | 0.99 | 2.6 | 0.5 | [178] | |

| Salvinorin A | >10,000 | >10,000 | 16 | [179] | |

| Samidorphan | 0.052 | 2.6 | 0.23 | [180] | |

| SIOM | 33 | 1.7 | >1,000 | [165] | |

| Spiradoline | 21 | >1,000 | 0.036 | [165] | |

| Sufentanil | 0.15 | 50 | 75 | [165] | |

| Tianeptine | 383 | >10,000 | >10,000 | [181] | |

| Tifluadom | 32 | 189 | 2.1 | [168] | |

| Tramadol | 2,120 | 57,700 | 42,700 | [170] | |

| (+)-Tramadol | 1,330 | 62,400 | 54,000 | [170] | |

| (−)-Tramadol | 24,800 | 213,000 | 53,500 | [170] | |

| U-47700 | 11.1 | 1,220 | 287 | [182] | |

| U-50488 | >1,000 | >1,000 | 0.12 | [165] | |

U-69593 |

>1,000 | >1,000 | 0.59 | [165] | |

| U-77891 | 2 | 105 | 2,300 | [183] | |

| Xorphanol | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.4 | [178] | |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. Assays were done mostly with cloned or cultured rodent receptors. | |||||

Usage

| Substance | Best estimate |

Low estimate |

High estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

Amphetamine- type stimulants |

34.16 | 13.42 | 55.24 |

| Cannabis | 192.15 | 165.76 | 234.06 |

| Cocaine | 18.20 | 13.87 | 22.85 |

| Ecstasy | 20.57 | 8.99 | 32.34 |

| Opiates | 19.38 | 13.80 | 26.15 |

| Opioids | 34.26 | 27.01 | 44.54 |

Opioid prescriptions in the US increased from 76 million in 1991 to 207 million in 2013.[185]

In the 1990s, opioid prescribing increased significantly. Once used almost exclusively for the treatment of acute pain or pain due to cancer, opioids are now prescribed liberally for people experiencing chronic pain. This has been accompanied by rising rates of accidental addiction and accidental overdoses leading to death. According to the International Narcotics Control Board, the United States and Canada lead the per capita consumption of prescription opioids.[186] The number of opioid prescriptions per capita in the United States and Canada is double the consumption in the European Union, Australia, and New Zealand.[187] Certain populations have been affected by the opioid addiction crisis more than others, including First World communities[188] and low-income populations.[189] Public health specialists say that this may result from the unavailability or high cost of alternative methods for addressing chronic pain.[190] Opioids have been described as a cost-effective treatment for chronic pain, but the impact of the opioid epidemic and deaths caused by opioid overdoses should be considered in assessing their cost-effectiveness.[191] Data from 2017 suggest that in the U.S. about 3.4 percent of the U.S. population are prescribed opioids for daily pain management.[192] Calls for opioid deprescribing have led to broad scale opioid tapering practices with little scientific evidence to support the safety or benefit for patients with chronic pain.

History

Naturally occurring opioids

Opioids are among the world's oldest known drugs.[193] The earliest known evidence of Papaver somniferum in a human archaeological site dates to the Neolithic period around 5,700–5,500 BCE. Its seeds have been found at Cueva de los Murciélagos in the Iberian Peninsula and La Marmotta in the Italian Peninsula.[194][195][196]

Use of the opium poppy for medical, recreational, and religious purposes can be traced to the fourth century BC, when ideograms on Sumerians clay tablets mention the use of "Hul Gil", a "plant of joy".[197][198][199] Opium was known to the Egyptians, and is mentioned in the Ebers Papyrus as an ingredient in a mixture for the soothing of children,[200][199] and for the treatment of breast abscesses.[201]

Opium was also known to the Greeks.[200] It was valued by

During the

Exactly when the world became aware of opium in India and China is uncertain, but opium was mentioned in the Chinese medical work K'ai-pao-pen-tsdo (973 AD)[199] By 1590 AD, opium poppies were a staple spring crop in the Subahs of Agra region.[206]

The physician Paracelsus (c. 1493–1541) is often credited with reintroducing opium into medical use in Western Europe, during the German Renaissance. He extolled opium's benefits for medical use. He also claimed to have an "arcanum", a pill which he called laudanum, that was superior to all others, particularly when death was to be cheated. ("Ich hab' ein Arcanum – heiss' ich Laudanum, ist über das Alles, wo es zum Tode reichen will.")[207] Later writers have asserted that Paracelsus' recipe for laudanum contained opium, but its composition remains unknown.[207]

Laudanum

The term laudanum was used generically for a useful medicine until the 17th century. After Thomas Sydenham introduced the first liquid tincture of opium, "laudanum" came to mean a mixture of both opium and alcohol.[207] Sydenham's 1669 recipe for laudanum mixed opium with wine, saffron, clove and cinnamon.[208] Sydenham's laudanum was used widely in both Europe and the Americas until the 20th century.[200][208] Other popular medicines, based on opium, included Paregoric, a much milder liquid preparation for children; Black-drop, a stronger preparation; and Dover's powder.[208]

The opium trade

Opium became a major colonial commodity, moving legally and illegally through trade networks involving India, the Portuguese, the Dutch, the British and China, among others.[209] The British East India Company saw the opium trade as an investment opportunity in 1683 AD.[206] In 1773 the Governor of Bengal established a monopoly on the production of Bengal opium, on behalf of the East India Company. The cultivation and manufacture of Indian opium was further centralized and controlled through a series of acts, between 1797 and 1949.[206][210] The British balanced an economic deficit from the importation of Chinese tea by selling Indian opium which was smuggled into China in defiance of Chinese government bans. This led to the First (1839–1842) and Second Opium Wars (1856–1860) between China and Britain.[211][210][209][212]

Morphine

In the 19th century, two major scientific advances were made that had far-reaching effects. Around 1804, German pharmacist Friedrich Sertürner isolated morphine from opium. He described its crystallization, structure, and pharmacological properties in a well-received paper in 1817.[211][213][208][214] Morphine was the first alkaloid to be isolated from any medicinal plant, the beginning of modern scientific drug discovery.[211][215]

The second advance, nearly fifty years later, was the refinement of the hypodermic needle by Alexander Wood and others. Development of a glass syringe with a subcutaneous needle made it possible to easily administer controlled measurable doses of a primary active compound.[216][208][199][217][218]

Morphine was initially hailed as a wonder drug for its ability to ease pain.

Codeine

Codeine was discovered in 1832 by Pierre Jean Robiquet. Robiquet was reviewing a method for morphine extraction, described by Scottish chemist William Gregory (1803–1858). Processing the residue left from Gregory's procedure, Robiquet isolated a crystalline substance from the other active components of opium. He wrote of his discovery: "Here is a new substance found in opium ... We know that morphine, which so far has been thought to be the only active principle of opium, does not account for all the effects and for a long time the physiologists are claiming that there is a gap that has to be filled."[223] His discovery of the alkaloid led to the development of a generation of antitussive and antidiarrheal medicines based on codeine.[224]

Semisynthetic and synthetic opioids

Synthetic opioids were invented, and biological mechanisms for their actions discovered, in the 20th century.

Heroin received little attention until it was independently synthesized by Felix Hoffmann (1868–1946), working for Heinrich Dreser (1860–1924) at Bayer Laboratories.[225] Dreser brought the new drug to market as an analgesic and a cough treatment for tuberculosis, bronchitis, and asthma in 1898. Bayer ceased production in 1913, after heroin's addictive potential was recognized.[211][226][227]

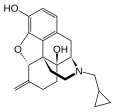

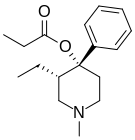

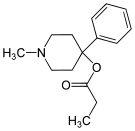

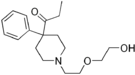

Several semi-synthetic opioids were developed in Germany in the 1910s. The first, oxymorphone, was synthesized from thebaine, an opioid alkaloid in opium poppies, in 1914.[228] Next, Martin Freund and Edmund Speyer developed oxycodone, also from thebaine, at the University of Frankfurt in 1916.[229] In 1920, hydrocodone was prepared by Carl Mannich and Helene Löwenheim, deriving it from codeine. In 1924, hydromorphone was synthesized by adding hydrogen to morphine. Etorphine was synthesized in 1960, from the oripavine in opium poppy straw. Buprenorphine was discovered in 1972.[228]

The first fully synthetic opioid was

Criminalization and medical use

Non-clinical use of opium was criminalized in the United States by the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, and by many other laws.[232][233] The use of opioids was stigmatized, and it was seen as a dangerous substance, to be prescribed only as a last resort for dying patients.[211] The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 eventually relaxed the harshness of the Harrison Act.[citation needed]

In the United Kingdom the 1926 report of the Departmental Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addiction under the Chairmanship of the President of the Royal College of Physicians reasserted medical control and established the "British system" of control—which lasted until the 1960s.[234]

In the 1980s the World Health Organization published guidelines for prescribing drugs, including opioids, for different levels of pain. In the U.S., Kathleen Foley and Russell Portenoy became leading advocates for the liberal use of opioids as painkillers for cases of "intractable non-malignant pain".[235][236] With little or no scientific evidence to support their claims, industry scientists and advocates suggested that people with chronic pain would be resistant to addiction.[211][237][235]

The release of

As a result, health care organizations and public health groups, such as Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, have called for decreases in the prescription of opioids.[237] In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a new set of guidelines for the prescription of opioids "for chronic pain outside of active cancer treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life care" and the increase of opioid tapering.[239]

"Remove the Risk"

In April 2019 the U.S.

Society and culture

Definition

The term "opioid" originated in the 1950s.[241] It combines "opium" + "-oid" meaning "opiate-like" ("opiates" being morphine and similar drugs derived from opium). The first scientific publication to use it, in 1963, included a footnote stating, "In this paper, the term, 'opioid', is used in the sense originally proposed by George H. Acheson (personal communication) to refer to any chemical compound with morphine-like activities".[242] By the late 1960s, research found that opiate effects are mediated by activation of specific molecular receptors in the nervous system, which were termed "opioid receptors".[243] The definition of "opioid" was later refined to refer to substances that have morphine-like activities that are mediated by the activation of opioid receptors. One modern pharmacology textbook states: "the term opioid applies to all agonists and antagonists with morphine-like activity, and also the naturally occurring and synthetic opioid peptides".[244] Another pharmacology reference eliminates the morphine-like requirement: "Opioid, a more modern term, is used to designate all substances, both natural and synthetic, that bind to opioid receptors (including antagonists)".[2] Some sources define the term opioid to exclude opiates, and others use opiate comprehensively instead of opioid, but opioid used inclusively is considered modern, preferred and is in wide use.[19]

Efforts to reduce recreational use in the US

In 2011, the Obama administration released a white paper describing the administration's plan to deal with the opioid crisis. The administration's concerns about addiction and accidental overdosing have been echoed by numerous other medical and government advisory groups around the world.[190][245][246][247]

As of 2015, prescription drug monitoring programs exist in every state, except for Missouri.[248] These programs allow pharmacists and prescribers to access patients' prescription histories in order to identify suspicious use. However, a survey of US physicians published in 2015 found that only 53% of doctors used these programs, while 22% were not aware that the programs were available to them.[249] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was tasked with establishing and publishing a new guideline, and was heavily lobbied.[250] In 2016, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published its Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, recommending that opioids only be used when benefits for pain and function are expected to outweigh risks, and then used at the lowest effective dosage, with avoidance of concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use whenever possible.[34] Research suggests that the prescription of high doses of opioids related to chronic opioid therapy (COT) can at times be prevented through state legislative guidelines and efforts by health plans that devote resources and establish shared expectations for reducing higher doses.[251]

On 10 August 2017, Donald Trump declared the opioid crisis a (non-FEMA) national public health emergency.[252]

Global shortages

Another idea to increase morphine availability is proposed by the

Recreational use

Opioids can produce strong feelings of euphoria[255] and are frequently used recreationally. Traditionally associated with illicit opioids such as heroin, prescription opioids are misused recreationally.

Classification

There are a number of broad classes of opioids:[260]

- Natural which have a different mechanism of action

- diacetylmorphine (morphine diacetate; heroin), nicomorphine (morphine dinicotinate), dipropanoylmorphine (morphine dipropionate), desomorphine, acetylpropionylmorphine, dibenzoylmorphine, diacetyldihydromorphine;[261][262]

- Semi-synthetic opioids: created from either the natural opiates or morphine esters, such as hydromorphone, hydrocodone, oxycodone, oxymorphone, ethylmorphine and buprenorphine;

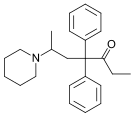

- Fully synthetic opioids: such as fentanyl, pethidine, levorphanol, methadone, tramadol, tapentadol, and dextropropoxyphene;

- .

- Endogenous opioids, non-peptide: Morphine, and some other opioids, which are produced in small amounts in the body, are included in this category.

- Natural opioids, non-animal, non-opiate: the leaves from kratom) contain a few naturally-occurring opioids, active via Mu- and Delta receptors. Salvinorin A, found naturally in the Salvia divinorum plant, is a kappa-opioid receptor agonist.[263]

Some minor opium

Amongst analgesics there are a small number of agents which act on the central nervous system but not on the opioid receptor system and therefore have none of the other (narcotic) qualities of opioids although they may produce euphoria by relieving pain—a euphoria that, because of the way it is produced, does not form the basis of habituation, physical dependence, or addiction. Foremost amongst these are

Other analgesics work peripherally (i.e., not on the brain or spinal cord). Research is starting to show that morphine and related drugs may indeed have peripheral effects as well, such as morphine gel working on burns. Recent investigations discovered opioid receptors on peripheral sensory neurons.[266] A significant fraction (up to 60%) of opioid analgesia can be mediated by such peripheral opioid receptors, particularly in inflammatory conditions such as arthritis, traumatic or surgical pain.[267] Inflammatory pain is also blunted by endogenous opioid peptides activating peripheral opioid receptors.[268]

It was discovered in 1953,[citation needed] that humans and some animals naturally produce minute amounts of morphine, codeine, and possibly some of their simpler derivatives like heroin and dihydromorphine, in addition to endogenous opioid peptides. Some bacteria are capable of producing some semi-synthetic opioids such as hydromorphone and hydrocodone when living in a solution containing morphine or codeine respectively.

Many of the

Salvinorin A is a unique selective, powerful ĸ-opioid receptor agonist. It is not properly considered an opioid nevertheless, because:

- chemically, it is not an alkaloid; and

- it has no typical opioid properties: absolutely no anxiolytic or cough-suppressant effects. It is instead a powerful hallucinogen.

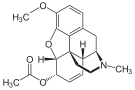

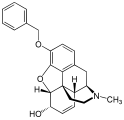

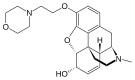

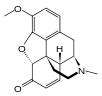

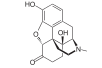

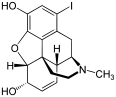

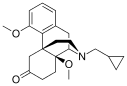

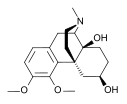

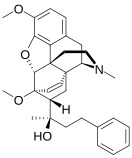

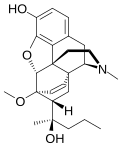

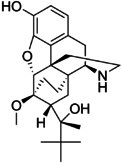

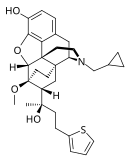

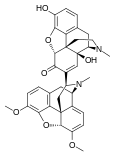

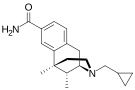

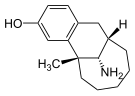

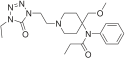

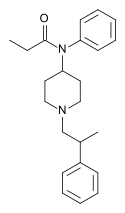

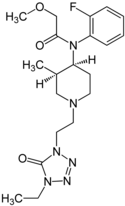

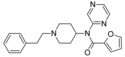

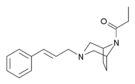

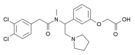

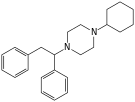

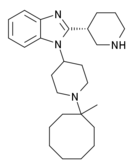

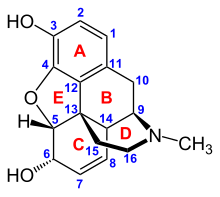

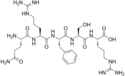

| Opioid peptides | Skeletal molecular images |

|---|---|

| Adrenorphin |

|

| Amidorphin |

|

| Casomorphin | |

| DADLE | |

| DAMGO |

|

| Dermorphin | |

| Endomorphin |

|

| Morphiceptin |

|

| Nociceptin |

|

| Octreotide |

|

| Opiorphin |

|

| TRIMU 5 |

|

Endogenous opioids

Opioid-peptides that are produced in the body include:

- Endorphins

- Enkephalins

- Dynorphins

- Endomorphins

Met-enkephalin is widely distributed in the CNS and in immune cells; [met]-enkephalin is a product of the proenkephalin gene, and acts through μ and δ-opioid receptors. leu-enkephalin, also a product of the proenkephalin gene, acts through δ-opioid receptors.

Dynorphin acts through κ-opioid receptors, and is widely distributed in the CNS, including in the spinal cord and hypothalamus, including in particular the arcuate nucleus and in both oxytocin and vasopressin neurons in the supraoptic nucleus.

Endomorphin acts through μ-opioid receptors, and is more potent than other endogenous opioids at these receptors.

Opium alkaloids and derivatives

Opium alkaloids

Phenanthrenes naturally occurring in (opium):

Preparations of mixed opium

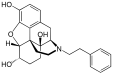

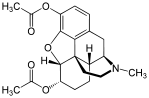

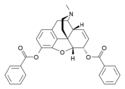

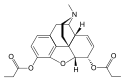

Esters of morphine

- Diacetylmorphine(morphine diacetate; heroin)

- Nicomorphine (morphine dinicotinate)

- Dipropanoylmorphine (morphine dipropionate)

- Diacetyldihydromorphine

- Acetylpropionylmorphine

- Desomorphine

- Methyldesorphine

- Dibenzoylmorphine

Ethers of morphine

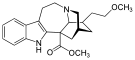

Semi-synthetic alkaloid derivatives

- Buprenorphine

- Etorphine

- Hydrocodone

- Hydromorphone

- Oxycodone (sold as OxyContin)

- Oxymorphone

Synthetic opioids

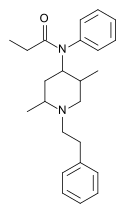

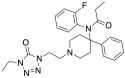

Anilidopiperidines

- Fentanyl (see also list of fentanyl analogues)

- Alphamethylfentanyl

- Alfentanil

- Sufentanil

- Remifentanil

- Carfentanyl

- Ohmefentanyl

Benzimidazoles

Benzimidazoles opioids are also known as nitazenes.

- Metodesnitazene (Metazene)

- Etodesnitazene (Etazene)

- Metonitazene

- Etonitazene

- Etonitazepyne

- Etonitazepipne

- Isotonitazene

- Clonitazene

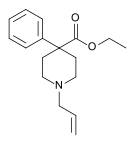

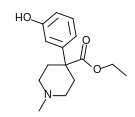

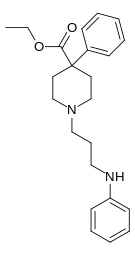

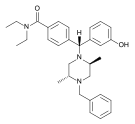

Phenylpiperidines

- Pethidine (meperidine)

- Ketobemidone

- MPPP

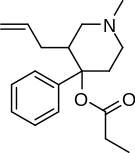

- Allylprodine

- Prodine

- PEPAP

- Promedol

Diphenylpropylamine derivatives

- Propoxyphene

- Dextropropoxyphene

- Dextromoramide

- Bezitramide

- Piritramide

- Methadone

- Dipipanone

- Levomethadyl acetate(LAAM)

- Difenoxin

- Diphenoxylate

- Loperamide (does cross the blood–brain barrier but is quickly pumped into the non-central nervous system by P-Glycoprotein. Mild opiate withdrawal in animal models exhibits this action after sustained and prolonged use including rhesus monkeys, mice, and rats.)

Benzomorphan derivatives

- Dezocine—agonist/antagonist

- Pentazocine—agonist/antagonist

- Phenazocine

Oripavine derivatives

- Buprenorphine—partial agonist

- Dihydroetorphine

- Etorphine

Morphinan derivatives

- Butorphanol—agonist/antagonist

- Nalbuphine—agonist/antagonist

- Levorphanol

- Levomethorphan

- Racemethorphan

Others

Allosteric modulators

Plain allosteric modulators do not belong to the opioids, instead they are classified as opioidergics.

Opioid antagonists

- Nalmefene

- Naloxone

- Naltrexone

- Methylnaltrexone (Methylnaltrexone is only peripherally active as it does not cross the blood–brain barrier in sufficient quantities to be centrally active. As such, it can be considered the antithesis of loperamide.)

- Naloxegol (Naloxegol is only peripherally active as it does not cross the blood–brain barrier in sufficient quantities to be centrally active. As such, it can be considered the antitheses of loperamide.)

Tables of opioids

Table of morphinan opioids

Table of non-morphinan opioids

| Table of non-morphinan opioids: click to | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ISBN 978-1-4377-1679-5. Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4377-1679-5.

Opiate is the older term classically used in pharmacology to mean a drug derived from opium. Opioid, a more modern term, is used to designate all substances, both natural and synthetic, that bind to opioid receptors (including antagonists).

- ^ "Opioids". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 11 May 2023. Archived from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ "Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission : Opiates or Opioids — What's the difference? : State of Oregon". www.oregon.gov. Archived from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4398-8240-5.

- )

- ^ "Carfentanil". www.drugbank.ca. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- PMID 15359207.

- ISBN 978-1-4214-2140-7.

- ^ "Drug Facts: Prescription Opioids". NIDA. June 2019. Archived from the original on 12 June 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "FDA requires strong warnings for opioid analgesics, prescription opioid cough products, and benzodiazepine labeling related to serious risks and death from combined use". FDA. 31 August 2016. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ "Status and Trend Analysis of Illict [sic] Drug Markets" (PDF). World Drug Report 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Report III: FDA Approved Medications for the Treatment of Opiate Dependence: Literature Reviews on Effectiveness & Cost- Effectiveness, Treatment Research Institute". Advancing Access to Addiction Medications: Implications for Opioid Addiction Treatment. p. 41. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- PMID 26339205.

- S2CID 21900231.

- ^ Gray E (4 February 2014). "Heroin Gains Popularity as Cheap Doses Flood the U.S". TIME.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

[A] number of studies, however, have also reported inadequate pain control in 40%–70% of patients, resulting in the emergence of a new type of epidemiology, that of 'failed pain control', caused by a series of obstacles preventing adequate cancer pain management.... The cancer patient runs the risk of becoming an innocent victim of a war waged against opioid abuse and addiction if the norms regarding the two kinds of use (therapeutic or nontherapeutic) are not clearly distinct. Furthermore, health professionals may be worried about regulatory scrutiny and may opt not to use opioid therapy for this reason.

- S2CID 25935364.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-540-38916-3.

In the strict sense, opiates are drugs derived from opium and include the natural products morphine, codeine, thebaine and many semi-synthetic congeners derived from them. In the wider sense, opiates are morphine-like drugs with non-peptidic structures. The older term opiates is now more and more replaced by the term opioids which applies to any substance, whether endogenous or synthetic, peptidic or non-peptidic, that produces morphine-like effects through action on opioid receptors.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-5947-6.

Opiate is a specific term that is used to describe drugs (natural and semi-synthetic) derived from the juice of the opium poppy. For example morphine is an opiate but methadone (a completely synthetic drug) is not. Opioid is a general term that includes naturally occurring, semi-synthetic, and synthetic drugs, which produce their effects by combining with opioid receptors and are competitively antagonized by nalaxone. In this context the term opioid refers to opioid agonists, opioid antagonists, opioid peptides, and opioid receptors.

- ISBN 978-0-8261-0974-3.

- ^ "21 U.S. Code § 802 – Definitions". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Definition of NARCOTIC". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ISBN 978-81-312-4371-8.

- ISBN 978-1-139-49354-3.

- PMID 26544675.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-60547-159-4.

- ^ "Codeine". Drugs.com. 15 May 2022. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- PMID 23150006.

- S2CID 51891341.

- S2CID 53567522.

- PMID 25267983.

- ^ PMID 21323559.

- ^ PMID 26977696.

- PMID 32110089.

- ^ ABIM Foundation, American Academy of Neurology, archivedfrom the original on 1 September 2013, retrieved 1 August 2013, which cites

- Silberstein SD (September 2000). "Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 55 (6): 754–62. PMID 10993991.

- Evers S, Afra J, Frese A, Goadsby PJ, Linde M, May A, et al. (September 2009). "EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine--revised report of an EFNS task force". European Journal of Neurology. 16 (9): 968–81. S2CID 9204782.

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (2011), Headache, Diagnosis and Treatment of, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, archived from the original on 29 October 2013, retrieved 18 December 2013

- Silberstein SD (September 2000). "Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 55 (6): 754–62.

- PMID 23364665.

- PMID 23986501.

- ^ American Headache Society, archived from the originalon 3 December 2013, retrieved 10 December 2013, which cites

- Bigal ME, Lipton RB (April 2009). "Excessive opioid use and the development of chronic migraine". Pain. 142 (3): 179–82. S2CID 27949021.

- Bigal ME, Serrano D, Buse D, Scher A, Stewart WF, Lipton RB (September 2008). "Acute migraine medications and evolution from episodic to chronic migraine: a longitudinal population-based study". Headache. 48 (8): 1157–68. PMID 18808500.

- Scher AI, Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Lipton RB (November 2003). "Factors associated with the onset and remission of chronic daily headache in a population-based study". Pain. 106 (1–2): 81–9. S2CID 29000302.

- Katsarava Z, Schneeweiss S, Kurth T, Kroener U, Fritsche G, Eikermann A, et al. (March 2004). "Incidence and predictors for chronicity of headache in patients with episodic migraine". Neurology. 62 (5): 788–90. S2CID 20759425.

- Bigal ME, Lipton RB (April 2009). "Excessive opioid use and the development of chronic migraine". Pain. 142 (3): 179–82.

- PMID 22786464.

- PMID 19187891.

- ^ "PAIN". Painjournalonline.com. 1 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- PMID 23874119.

- PMID 22267615.

- PMID 19304445.

- (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ISBN 978-3-540-79842-2.

- PMID 17218808.

- ^ PMID 21156892.

- S2CID 23865647.

- PMID 22917039.

- S2CID 30521239.

- ^ Van Amburgh JA. "Do Cough Remedies Work?". Medscape. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- PMID 20172264.

- PMID 26461071.

- ^ "Press Announcements - FDA approves Movantik for opioid-induced constipation". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- PMID 21746829.

- PMID 23529525.

- PMID 33289989.

- PMID 33630086.

- ^ "Restless Legs Syndrome | Baylor Medicine". www.bcm.edu. Archived from the original on 5 November 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- S2CID 19181545.

- ^ PMID 16717269.

- S2CID 24720660.

- PMID 19489204.

- S2CID 25941322.

- ^ Schneider JP (2010). "Rational use of opioid analgesics in chronic musculoskeletal pain". J Musculoskel Med. 27: 142–148. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- PMID 30921976.

- PMID 31073926.

- ^ Stephens E (23 November 2015). "Opioid Toxicity". Medscape. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

The CDC reported that methadone contributed to 31.4% of opioid-related deaths in the United States from 1999–2010. Methadone also accounted for 39.8% of all single-drug opioid-related deaths. The overdose death rate associated with methadone was significantly higher than that associated with other opioid-related deaths among multidrug and single-drug deaths.

- ^ PMID 20091598.

- ^ "Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2016" (PDF). CDC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- PMID 21147985.

- PMID 15731628.

- S2CID 35138704.

- S2CID 30963675.

- S2CID 37434490.

- from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- PMID 23533255.

- PMID 11068022.

- PMID 8851162.

- (PDF) from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- S2CID 29229782.

- PMID 6546809.

- S2CID 33168040.

- S2CID 22321634.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-856698-4.

- S2CID 8017503.

- PMID 23627782.

- PMID 30569508.

- S2CID 26082561.

- S2CID 17830622.

- PMID 24167729.

- PMID 22983894.

- S2CID 32705478.

- S2CID 2488112.

- ^ "UCSF Study Finds Medical Marijuana Could Help Patients Reduce Pain with Opiates". UC San Francisco. 6 December 2011. Archived from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- S2CID 4823659.

- from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- PMID 30561481.

- S2CID 39058371.

- S2CID 23733242.

- PMID 25520993.

- S2CID 42872181.

- ^ PMID 24883055.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-934465-13-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4665-9635-1.

- PMID 26557892.

- PMID 26908305.

- PMID 36106667.

- from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- PMID 30851171.

- PMID 25207610.

- PMID 17227289.

- PMID 16939923.

- S2CID 13641423.

- PMID 17576856.

- PMID 16973981.

- S2CID 49614405.

- PMID 30552274.

- S2CID 22690630.

- S2CID 17757207.

- S2CID 39647898.

- S2CID 45555785.

- from the original on 14 December 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- PMID 21225380.

- PMID 20021351.

- PMID 18717507.

- PMID 19655103.

- S2CID 9713245.

- ^ PMID 25702934.

- PMID 30343356.

- ^ PMID 30299887.

- PMID 23414717.

- PMID 19193821.

- PMID 22786453.

- PMID 22289236.

- PMID 19181448.

- ^ ABIM Foundation, American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, archivedfrom the original on 11 September 2014, retrieved 24 February 2014, which cites

- Weiss MS, Bowden K, Branco F, et al. (2011). "Opioids Guideline". In Hegmann KT (ed.). Occupational medicine practice guidelines : evaluation and management of common health problems and functional recovery in workers (online March 2014) (3rd ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-615-45227-2.

- Weiss MS, Bowden K, Branco F, et al. (2011). "Opioids Guideline". In Hegmann KT (ed.). Occupational medicine practice guidelines : evaluation and management of common health problems and functional recovery in workers (online March 2014) (3rd ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. p. 11.

- S2CID 47576095.

- S2CID 43241757.

- PMID 24358001.

- PMID 21125020.

- PMID 21391934.

- S2CID 53023743.

- ^ PMID 23933900.

- PMID 31425552.

- S2CID 218780209.

- PMID 23720250.

- PMID 28553701.

- PMID 30642329.

- PMID 30580317.

- ISBN 978-0-443-06959-8.

- ISBN 978-0-07-110515-6.

- ISBN 978-0-323-11374-8.

The lipid solubility of hydromorphone lies between morphine and fentanyl, but is closer to that of morphine.

- PMID 25934430.

- PMID 30528374.

- from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- PMID 24978316.

- S2CID 8785003.

- PMID 6088255.

- ^ PMID 11960505.

- ^ PMID 8114680.

- from the original on 21 November 2023. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ PMID 11197347.

- ^ PMID 2986989.

- ^ ISSN 0171-2004.

- ^ PMID 7562497.

- S2CID 6942770.

- PMID 8955860.

- PMID 10991912.

- PMID 8719422.

- PMID 6300816.

- PMID 15988468.

- PMID 19027293.

- ^ PMID 16433932.

- PMID 12192085.

- PMID 19282177.

- PMID 25026323.

- PMID 32533977.

- PMID 2542556.

- ^ "Annual prevalence of use of drugs, by region and globally, 2016". World Drug Report 2018. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ Volkow ND. "America's Addiction to Opioids: Heroin and Prescription Drug Abuse". DrugAbuse.GOV. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Archived from the original on 25 May 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "Narcotic Drugs Stupéfiants Estupefacientes" (PDF). INTERNATIONAL NARCOTICS CONTROL BOARD. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ^ "Opioid Consumption Data | Pain & Policy Studies Group". Painpolicy.wisc.edu. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- PMID 22879752.

- ^ "Socially disadvantaged Ontarians being prescribed opioids on an ongoing basis and at doses that far exceed Canadian guidelines". Ices.on.ca. 25 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Avoiding Abuse, Achieving a Balance: Tackling the Opioid Public Health Crisis" (PDF). College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. 8 September 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- S2CID 197664630.

- S2CID 19047621.

- PMID 22437502.

Opium is one of the world's oldest drugs, and its derivatives morphine and codeine are among the most used clinical drugs to relieve severe pain.

- ISBN 978-1-59874-988-5. Archivedfrom the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Kunzig R, Tzar J (1 November 2002). "La Marmotta". Discover. Archived from the original on 22 January 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-84217-514-9. Archivedfrom the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Kritikos PG, Papadaki SP (1967). "The history of the poppy and of opium and their expansion in antiquity in the eastern Mediterranean area". Bulletin on Narcotics. XIX (4). Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Sonnedecker G (1962). "Emergence of the Concept of Opiate Addiction". Journal Mondial de Pharmacie. 3: 275–290.

- ^ PMID 8390660.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- CiteSeerX 10.1.1.846.221.

- S2CID 25919738.

- S2CID 26539333.

Sedare dolorem opus divinum est – an old Latin inscription – means "alleviating pain is the work of the divine". This inscription is often attributed to either Hippocrates of Kos or Galen of Pergamum, but it is most likely an anonymous proverb

- ISBN 978-0-620-23435-1.

- from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ a b c Asthana SN (1954). "The Cultivation of the Opium Poppy in India". Bulletin on Narcotics (3). Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ a b c Sigerist HE (1941). "Laudanum in the Works of Paracelsus" (PDF). Bull. Hist. Med. 9: 530–544. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ PMID 10764185.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ a b Deming S (2011). "The Economic Importance of Indian Opium and Trade with China on Britain's Economy, 1843–1890". Economic Working Papers. 25 (Spring). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rinde M (2018). "Opioids' Devastating Return". Distillations. 4 (2): 12–23. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-230-29646-6. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2018.)

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help - PMID 27942064.

- ISBN 978-0-674-02990-3.

- PMID 26281720.

- PMID 15589680.

- ISBN 978-1-4833-2188-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4522-6601-5.

- ^ a b Trickey E (4 January 2018). "Inside the Story of America's 19th-Century Opiate Addiction". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-683-07588-5. Archivedfrom the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- Chemical Heritage Foundation. Archivedfrom the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-312-20667-3.

- .

- ISBN 978-1-59477-399-0. Archivedfrom the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ "Felix Hoffmann". Science History Institute. June 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-4987-0428-1. Archivedfrom the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

Bayer registered the name heroin in June, 1898.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4408-3983-2. Archivedfrom the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ Crow JM (3 January 2017). "Addicted to the cure". Chemistry World. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-203-63309-0. Archivedfrom the original on 23 December 2015.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: Fentanyl and Synthetic Opioids" (PDF). Drug Policy Alliance. September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ "Laws Learn about the laws concerning opioids from the 1800s until today". The National Alliance of Advocates for Buprenorphine Treatment. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ White WL. "The Early Criminalization of Narcotic Addiction" (PDF). William White Papers. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- PMID 16212730.

- ^ a b Jacobs H (26 May 2016). "This one-paragraph letter may have launched the opioid epidemic". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- S2CID 23959703.

- ^ PMID 27400351.

- ISBN 978-1-62040-251-1.

- PMID 26987082.

- ^ "FDA launches public education campaign to encourage safe removal of unused opioid pain medicines from homes". FDA. 24 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ "opioid: definition of opioid in Oxford dictionary (American English) (US)". www.oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

Opioid: 1950s: from opium + -oid.

- S2CID 38073529.

In this paper, the term, 'opioid', is used in the sense originally proposed by DR. GEORGE H. ACHESON (personal communication) to refer to any chemical compound with morphine-like activities.

- PMID 4867058.

- ISBN 978-81-312-1158-8.

- ^ "Epidemic: Responding to America's Prescription Drug Abuse Crisis" (PDF). The White House. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2012.

- ^ "First Do No Harm: Responding to Canada's Prescription Drug Crisis" (PDF). March 2013. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ "UK: Task Force offers ideas for opioid addiction solutions". Delhidailynews.com. 11 June 2014. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ Kite A (29 April 2018). "Every state but Missouri has opioid drug tracking. Why are senators against it?". The Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- PMID 25732500.

- ^ Perrone M (20 December 2015). "Painkiller politics: Effort to curb prescribing under fire". Philly.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- PMID 26476264.

- Washington Post. Archivedfrom the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ "Feasibility Study on Opium Licensing in Afghanistan for the Production of Morphine and Other Essential Medicines". ICoS. September 2005. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ "Assuring Availability of Opioid Analgesics" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2009.

- PMID 26811699.

The opioid effects transcending analgesia include sedation, respiratory depression, constipation and a strong sense of euphoria.

- PMID 19630724. Archived from the original(PDF) on 15 June 2010.

- PMID 19278795.

- ^ "Prescription Opioid Overdose Data | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center". www.cdc.gov. 31 August 2018. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ "Chronic Pain Management and Opioid Misuse: A Public Health Concern (Position Paper)". American Academy of Family Physicians. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ "Opioid drug". Science Daily. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Esters of Morphine". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 1953. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ "Esters of Morphine Opioids". eOpiates. 28 May 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- PMID 12192085.

- S2CID 24226747.

- PMID 9749830.

- S2CID 25453057.

- PMID 19157985.

- S2CID 40205179.

- PMID 17765420.

External links

- Opioid Withdrawal Symptoms Archived 10 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine—Information about Opioid and opiate withdrawal issues

- World Health Organization guidelines for the availability and accessibility of controlled substances

- CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016

- Reference list to the previous publication

- Links to all language versions of the previous publication

- Video: Opioid side effects (Vimeo) (YouTube)—A short educational film about the practical management of opioid side effects.