Moderate Republicans (France, 1871–1901)

Moderate Republicans Républicains modérés | |

|---|---|

| Leader(s) | Republicanism |

| Political position | Centre-left[6][7][8][a] |

| Colours | Orange |

^ a: However, Opportunist Republicans was also classified as "Left-wing"[9][10] or "Centre".[11][12] | |

|

|---|

The Moderates or Moderate Republicans (

Although considered

They were further divided into the National Republican Association (Association nationale républicaine) and the Liberal Republican Union (Union libérale républicaine) in 1888 and 1889, respectively.

History

Origins

The

Divisions

After the

Moving to the right

In January 1879, the Republican

During the late 1870s and 1880s, the Republican majority launched an education reform with the

In the legislative elections of 1885, the republican consolidation was confirmed. Even if popularly won by the Conservative Union of Armand de Mackau, the elections guaranteed a solid republican majority in the Chamber. In fact, until the election the two republican groups had been reunited in a new political party guided by President Grévy and his close ally Jules Ferry, namely the Democratic Union, born of the fusion of the Republican Left and the Republican Union. However, the republican Prime Minister Ferry was forced to resign in 1885 after a political scandal known as the Tonkin Affair and President Grévy also resigned his office in 1887 after a corruption scandal involving his son-in-law. The Moderate Republicans, seriously challenged, survived only thanks to the support of the Radical Republicans of René Goblet and worries about the rise of a new political phenomenon called revanchism, the desire for revenge against the German Empire after the defeat of 1871.

Final divisions and decline

National Republican Association Association nationale républicaine | |

|---|---|

| Chairman(s) | Republicanism |

| Political position | Centre-right |

| Colours | Blue |

Staff (1888) ca. 110 | |

The revanchist ideas were strong in the France of the

In the face of the rise of Boulanger, the republican leaders were divided. From one side, the old republican moderate wing, composed by prominent personalities like Jules Ferry, Maurice Rouvier and

In the 1890s, the Moderate Republican parable ended as the

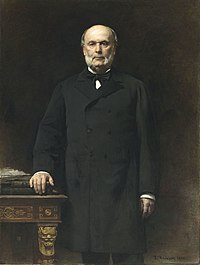

Prominent members

Electoral results

Presidential elections

| Election year | Candidate | No. of first round votes | % of first round vote | No. of second round votes | % of second round vote | Won/Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1873 | Jules Grévy | 1 | 0.3% | Loss | ||

1879

|

Jules Grévy | 563 | 84.0% | Won | ||

1885

|

Jules Grévy | 457 | 79.4% | Won | ||

1887

|

François Sadi Carnot

|

303 | 35.7% | 616 | 75.0% | Won |

1894

|

Jean Casimir-Perier | 451 | 53.4% | Won | ||

1895

|

Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau | 184 | 23.8% | Loss | ||

1899

|

Émile Loubet | 483 | 59.5% | Won | ||

Legislative elections

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||

| Election year | No. of overall votes |

% of overall vote |

No. of overall seats won |

+/– | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1871 | Unknown (3rd) | 17.5% | 112 / 638

|

New

|

|

| 1876 | 2,674,540 (1st) | 36.2% | 193 / 533

|

||

| 1877[a] | 4,860,481 (1st) | 60.0% | 313 / 521

|

||

| 1881 | 2,226,247 (2nd) | 31.0% | 168 / 545

|

||

| 1885[b] | 2,711,890 (1st) | 34.2% | 200 / 584

|

||

| 1889 | 2,974,565 (1st) | 37.4% | 216 / 578

|

||

| 1893 | 3,608,722 (1st) | 48.6% | 279 / 574

|

||

| 1898[c] | 3,518,057 (1st) | 43.4% | 254 / 585

|

||

| |||||

See also

- France during the 19th century

- History of the Left in France

- Opportunism

- Politics of France

Bibliography

- Abel Bonnard (1936). Les Modérés. Grasset. 330 p.

- Francois Roth (dir.) (2003). Les modérés dans la vie politique française (1870-1965). Nancy: University of Nancy Press. 562 p. ISBN 2-86480-726-2.

- Gilles Dumont, Bernard Dumont and Christophe Réveillard (dir.) (2007). La culture du refus de l’ennemi. Modérantisme et religion au seuil du XXIe siècle. University of Limoges Press. Bibliothèque européenne des idées. 150 p.

References

- ^ ISBN 9782870274019.

- ISBN 9780231543804.

- ISBN 9782011818751.

- ISBN 9782130493884.

- ISBN 9782735104246.

- ^ Adam D. Sheingate, ed. (2021). The Rise of the Agricultural Welfare State: Institutions and Interest Group Power in the United States, France, and Japan. Princeton University Press. p. 42.

- ^ Jean-Numa Ducange, Elisa Marcobelli, ed. (2021). Selected Writings of Jean Jaurès: On Socialism, Pacifism and Marxism. Springer Nature. p. xi.

- ^ Samuel Raybone, ed. (2020). Gustave Caillebotte as Worker, Collector, Painter. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 4.

- ISBN 9782200615451.

- ISBN 9782213656601.

- ISBN 9789052013176.

- ISBN 9782213664378.

- ^ Philippe Vigier (1967). La Seconde République. PUF, coll. Que sais-je ?. p. 127.

- ^ Francis Démier (2000). La France du XIXe siècle. Éditions du Seuil. p. 602.

- ^ Dominique Lejeune (2011). La France des débuts de la IIIe République, 1870-1896. Armand Colin. p. 9.

- ^ Michel Winock (2007). Clemenceau. Éditions Perrin. p. 21.

- ^ François Caron (1985). La France des patriotes (de 1851 à 1918). Fayar. p. 384.

- ^ Georges-Léonard Hémeret; Janine Hémeret (1981). Les présidents : République française. Filipacchi. p. 237.

- ^ Spuller, p. 10.

- ^ G. Davenay (30 August 1894). "L'Association nationale républicaine". Le Figaro.

- .

- ^ "L'Association républicaine du Centenaire de 1789". Le Temps. 9–19 February 1888.

- ^ Stephen Pichon (24 June 1888). "Un Parti". La Justice.

- ^ THE PANAMA SCANDALS; An Exciting Scene in the French Chamber of Deputies. March 30, 1897

- ^ Charles Morice; Henry Jarzuel (11 August 1894). "La Constitution". Le Figaro.

- ^ Le Figaro, 27 February 1899

- ^ Le Figaro, 9 February 1902

- ^ Auguste Avril (19 November 1903). "Les Progressistes". Le Figaro.